Why Geopolitical Chaos Isn’t Pushing Oil Prices Higher

- Major crises in producers like Venezuela, Russia, and Iran are largely priced in because their effective supply is already constrained or discounted.

- Slower demand growth driven by efficiency gains, EV adoption, and energy transition policies may limit an oil price shock.

- Strategic reserves, OPEC+ spare capacity, and diversified energy systems dampen panic, keeping oil prices anchored despite global turmoil.

If you’ve been watching global headlines lately, it would be easy to assume oil prices would be sky-high: a major oil-reserve country mired in crisis, sanctions on perennial producers, regional conflicts simmering, and social unrest in several exporters. And yet Brent and WTI have been languishing around $60 a barrel, a level that, a decade ago, most analysts would have dismissed as impossible in such conditions

What’s happening?

At first glance, the logic of oil pricing should be straightforward: supply risk should mean higher prices. But today’s market tells a very different story, one where geopolitical shocks don’t automatically translate into price shocks.

The Changing Nature of Supply Risk

Take Venezuela, the poster child of dysfunctional oil production. Sitting on the world’s largest proven crude reserves, you’d expect its political upheavals to roil markets. In reality, Venezuela’s output has already shrivelled over years of mismanagement, sanctions, and capital flight. What matters most to traders isn’t headline reserve totals, it’s actual barrels available to buy, ship, refine, and burn. Caracas no longer moves global supply balance sheets in any meaningful way. This is also unlikely to change with the US intervention, as companies require a stable regime to operate in. Such is a long way away in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, traditional trouble spots like Russia and Iran are constrained by sanctions more than geology. Their exports find buyers, but often at steep discounts and under complex legal and logistical workarounds. Oil markets have, over the past decades, learned to price sanctions as part of the baseline, not an extraordinary disturbance.

Demand Is the New Wild Card

What’s truly different now isn’t just supply, it’s demand behavior.

A decade ago, oil demand growth was almost a given. Emerging markets industrialized en masse; transportation fuel demand climbed inexorably; industrial energy use marched upward. Today, that certainty has fractured. Efficiency gains, electrification of vehicles, alternative fuels and regulatory pressures have altered the trajectory. Even in markets where oil demand hasn’t peaked, it’s plateauing, or at best growing slowly.

In today’s world, traders don’t simply ask: “Will supply tighten?”

They increasingly ask: “Will demand growth falter before supply truly tightens?”

That shift matters. A potential drop in consumption, driven by EV uptake, fuel efficiency, and energy transition policies, is far more price-inhibiting than any single supply disruption is price-supporting.

Strategic Stocks and Spare Capacity

Another layer to this puzzle is the buffering effect of strategic reserves and spare capacity. Where once a refinery outage or pipeline strike would send instant ripples through crude curves, today there are more mechanisms to cushion temporary disruptions. Strategic Petroleum Reserves, coordinated production management by OPEC+, and stock builds in consuming economies are all part of a toolkit that dampens sharp price spikes.

In other words: markets aren’t as quick to panic. They assume that if one area falters, another can fill gaps at least temporarily. That assumption has become baked into pricing algorithms and risk premia.

A Broader Shift Underway

Perhaps the most profound change isn’t in oil markets alone, it’s in the broader energy landscape. The global energy transition has expanded the palette of strategic fuels. Renewables and gas are increasingly central to power generation. Electrification is eating into transportation demand. Energy systems are becoming more localized and less dependent on seaborne crude. These trends don’t make oil irrelevant—but they do reduce the hammer-lock that geopolitical risk once had on prices.

The result: oil markets behaving less like they used to.

So, Is Oil Still Critical?

Yes, but in a different way.

Oil remains essential for aviation, shipping, petrochemicals, and many industrial processes. It’s not suddenly optional. But the market’s muted response to geopolitical disruption suggests something structural has changed.

Oil is still a strategic commodity, but it’s no longer the sole arbiter of energy security. Its price now reflects not only geopolitical risk, but demand uncertainty, competitive fuels, and a world in transition. And in that world, crises that once guaranteed a spike in prices now barely trouble the market’s equilibrium. That’s not just a market signal, it’s a reflection of a broader energy evolution that’s well underway.

By Leon Stille for Oilprice.com

- Major crises in producers like Venezuela, Russia, and Iran are largely priced in because their effective supply is already constrained or discounted.

- Slower demand growth driven by efficiency gains, EV adoption, and energy transition policies may limit an oil price shock.

- Strategic reserves, OPEC+ spare capacity, and diversified energy systems dampen panic, keeping oil prices anchored despite global turmoil.

If you’ve been watching global headlines lately, it would be easy to assume oil prices would be sky-high: a major oil-reserve country mired in crisis, sanctions on perennial producers, regional conflicts simmering, and social unrest in several exporters. And yet Brent and WTI have been languishing around $60 a barrel, a level that, a decade ago, most analysts would have dismissed as impossible in such conditions

What’s happening?

At first glance, the logic of oil pricing should be straightforward: supply risk should mean higher prices. But today’s market tells a very different story, one where geopolitical shocks don’t automatically translate into price shocks.

The Changing Nature of Supply Risk

Take Venezuela, the poster child of dysfunctional oil production. Sitting on the world’s largest proven crude reserves, you’d expect its political upheavals to roil markets. In reality, Venezuela’s output has already shrivelled over years of mismanagement, sanctions, and capital flight. What matters most to traders isn’t headline reserve totals, it’s actual barrels available to buy, ship, refine, and burn. Caracas no longer moves global supply balance sheets in any meaningful way. This is also unlikely to change with the US intervention, as companies require a stable regime to operate in. Such is a long way away in Venezuela.

Meanwhile, traditional trouble spots like Russia and Iran are constrained by sanctions more than geology. Their exports find buyers, but often at steep discounts and under complex legal and logistical workarounds. Oil markets have, over the past decades, learned to price sanctions as part of the baseline, not an extraordinary disturbance.

Demand Is the New Wild Card

What’s truly different now isn’t just supply, it’s demand behavior.

A decade ago, oil demand growth was almost a given. Emerging markets industrialized en masse; transportation fuel demand climbed inexorably; industrial energy use marched upward. Today, that certainty has fractured. Efficiency gains, electrification of vehicles, alternative fuels and regulatory pressures have altered the trajectory. Even in markets where oil demand hasn’t peaked, it’s plateauing, or at best growing slowly.

In today’s world, traders don’t simply ask: “Will supply tighten?”

They increasingly ask: “Will demand growth falter before supply truly tightens?”

That shift matters. A potential drop in consumption, driven by EV uptake, fuel efficiency, and energy transition policies, is far more price-inhibiting than any single supply disruption is price-supporting.

Strategic Stocks and Spare Capacity

Another layer to this puzzle is the buffering effect of strategic reserves and spare capacity. Where once a refinery outage or pipeline strike would send instant ripples through crude curves, today there are more mechanisms to cushion temporary disruptions. Strategic Petroleum Reserves, coordinated production management by OPEC+, and stock builds in consuming economies are all part of a toolkit that dampens sharp price spikes.

In other words: markets aren’t as quick to panic. They assume that if one area falters, another can fill gaps at least temporarily. That assumption has become baked into pricing algorithms and risk premia.

A Broader Shift Underway

Perhaps the most profound change isn’t in oil markets alone, it’s in the broader energy landscape. The global energy transition has expanded the palette of strategic fuels. Renewables and gas are increasingly central to power generation. Electrification is eating into transportation demand. Energy systems are becoming more localized and less dependent on seaborne crude. These trends don’t make oil irrelevant—but they do reduce the hammer-lock that geopolitical risk once had on prices.

The result: oil markets behaving less like they used to.

So, Is Oil Still Critical?

Yes, but in a different way.

Oil remains essential for aviation, shipping, petrochemicals, and many industrial processes. It’s not suddenly optional. But the market’s muted response to geopolitical disruption suggests something structural has changed.

Oil is still a strategic commodity, but it’s no longer the sole arbiter of energy security. Its price now reflects not only geopolitical risk, but demand uncertainty, competitive fuels, and a world in transition. And in that world, crises that once guaranteed a spike in prices now barely trouble the market’s equilibrium. That’s not just a market signal, it’s a reflection of a broader energy evolution that’s well underway.

By Leon Stille for Oilprice.com

UK North Sea Oil Enters Survival Mode as Investment Dries Up

- UK North Sea oil and gas endured its toughest year in decades in 2025, with investment pulled back sharply and offshore exploration falling to zero.

- The government’s decision to keep the 78% Energy Profits Levy in place until 2030 has deepened industry pessimism.

- Facing punitive taxes and shrinking activity, operators are turning to mergers and acquisitions to survive.

The once-thriving UK North Sea oil and gas province survived 2025, the most difficult year since the 1960s when hydrocarbons were first discovered in the basin.

Oil and gas production from the mature fields continued to decline last year, while uncertainties increased as industry expected changes to the UK government’s policy that places an enormous tax burden on operators without incentives or investment allowances. Companies active in the UK offshore oil and gas sector reduced investments and froze plans in the face of heightened uncertainty.

With the pullback in investment and the government’s reluctance to award new licenses, exploration in the UK North Sea plunged to an all-time low. Due to unpredictable fiscal policies, 2025 became the first year since 1960 without a single exploration well in Britain’s offshore, consultancy Wood Mackenzie has warned.

Windfall Tax Suppresses Investment

The UK oil and gas industry received clarity at the end of 2025 about the fiscal regime that it was awaiting for more than six months.

The government removed most of the uncertainty with the Autumn Budget in November. But it left the windfall tax unchanged as-is until 2030—contrary to the pleas and warnings from the sector that the total tax rate, including the windfall tax, of 78% and no incentives or allowances would essentially tax the industry and its supply chain to death.

In fact, the only certainty that the industry received was that the punitive tax, officially known as Energy Profits Levy (EPL), remains until the end of the decade. For 2025, the levy was triggered by oil prices above $76 per barrel or natural gas prices 59 pence per therm. Oil prices were mostly below the threshold, but gas prices have remained above 59p a therm, which triggers the 35% windfall tax on profits.

Last year was terrible for the UK North Sea. Industry sentiment is that the horrible years aren’t over and an accelerated decline in investment and exploration would kill the industry and increase Britain’s need for oil and gas imports, exposing one of Europe’s top economies even more to the volatile international oil, gas, and LNG markets.

The windfall tax, first introduced by a Conservative government at the height of the 2022 energy crisis and now extended under Labour, would wipe out all non-essential investment in the UK shelf, as it would compete with friendlier tax jurisdictions, according to WoodMac.

“The government turned down £50 billion of investment for the UK and the chance to protect the jobs and industries that keep this country running,” Offshore Energies UK chief executive, David Whitehouse, said in response to the decision to keep the windfall tax as-is.

“Instead, they’ve chosen a path that will see 1,000 jobs continue to be lost every month, more energy imports and a contagion across supply chains and our industrial heartlands,” Whitehouse added.

The Aberdeen & Grampian Chamber of Commerce said it’s “Lights out for North Sea oil and gas as Chancellor keeps windfall tax.”

The Chamber’s chief executive, Russell Borthwick, commented that instead of heeding advice from industry, “the UK Government has instead opted for a cliff-edge end to North Sea production and to tax the industry to death inside five years. Jobs will be lost in their thousands as a direct result of this government’s failure to act.”

The levy has prompted many companies to halt investment in the UK and move to cut workforce numbers in recent years.

The latest announcement came from one of the top independent producers, Harbour Energy, which last month said it expects to reduce employee numbers by another 100, on top of 600 jobs already eliminated since 2023.

Harbour Energy’s chief executive, Linda Cook, told the Financial Times at the end of December that the UK is “the worst of the fiscal environments among all the countries that [we] operate in.”

Due to the fiscal regime, the UK industry is forced to compete with other jurisdictions with “one arm tied behind its back”, Cook told FT.

Survival of the Fittest Mergers

In the unfriendly fiscal environments, operators in the UK North Sea are resorting to alternative solutions to boost profits and create value for shareholders. Mergers have become the most common of these solutions as the industry consolidates to cope with the punitive tax rate.

Last month, Harbour Energy announced an acquisition in the UK North Sea as the industry seeks to weather the crippling effects of the UK windfall tax.

“This transaction is an important step for Harbour in the UK North Sea, building on the action we’ve already taken to sustain our position in the basin given the ongoing fiscal and regulatory challenges,” said Scott Barr, Managing Director of Harbour’s UK Business Unit, commenting on the deal to buy Waldorf Energy Partners Ltd and Waldorf Production Ltd, currently in administration, for $170 million.

Harbour Energy became the latest operator in the UK to announce acquisitions, following the launch of the 50/50 joint venture of Shell and Equinor, which combined their offshore UK oil and gas operations in a new company, Adura. Earlier in December, French supermajor TotalEnergies said it would merge its upstream UK business with NEO NEXT to create the biggest independent oil and gas producer in Britain, NEO NEXT+.

Analysts expect the consolidation drive to continue, while the industry continues to call on the government to reform the fiscal regime.

“Restoring North Sea investment does not mean abandoning climate commitments; it is necessary to safeguard jobs, stabilise the economy, and maintain a bridge to a cleaner energy future,” UK’s energy and chemicals group Ineos, which has halted UK investments, said last month.

“How can businesses invest in that future if they are being driven to ruin?”

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

Mexico’s Crude Exports Slide as Refining Finally Reawakens

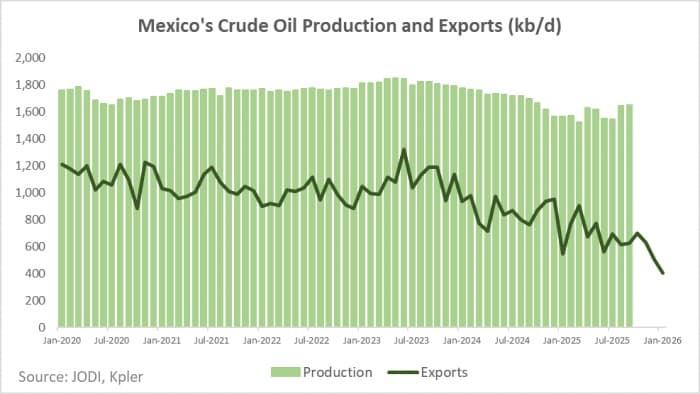

- Mexico’s crude exports have fallen from around 1.1 million b/d in 2020 to 503,000 b/d in December 2025 – the lowest level in the 21st century, while production has declined far less, signalling a shift toward domestic refining.

- A refining reset launched in 2019 has lifted utilization across much of the system, with five of seven refineries running above 50% by late 2025.

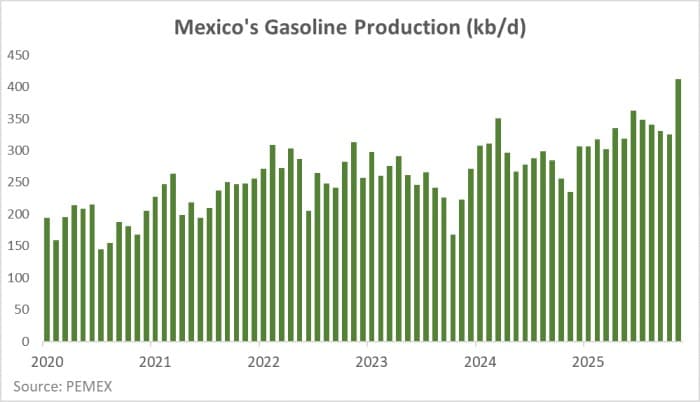

- Mexico’s refining gains are now visible in fuel output and trade, with diesel and gasoline production rising and US fuel imports easing, although the recovery remains uneven.

Mexico’s crude oil exports are shrinking fast – and this time the decline is not just a symptom of upstream exhaustion. Average crude exports have fallen from about 1.1 million b/d in 2020 to roughly 665,000 b/d in 2025, a near 40% drop. In December 2025, Mexico’s exports reached 503,000 b/d, marking a 21st century minimum. The drastic decrease is even starker for Maya, Mexico’s flagship heavy grade: December exports slid to 253,000 b/d, down 86% from 2020 levels. Ironically, the rapid decline in Mexico’s crude exports happens at the same time as the Trump administration seeks to gain control over Venezuela’s heavy sour barrels.

Production, by contrast, has eased far more modestly, declining by only around 100,000 b/d over the same period. That widening gap points to a structural shift: Mexico is exporting less crude largely because it needs more oil for its refineries at home. With roughly 60% of exports historically flowing to the US, the pullback has become increasingly visible in trade, signaling first good news from the industry to President Sheinbaum’s administration – the long-promised revival of domestic refining is beginning to show up in numbers.

The pivot traces back to 2019, when former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador launched a project to reset Mexico’s National Refining Systema (Sistema Nacional de Refinación, SNR). After decades of underinvestment and chronic underutilization, the strategy aimed to rehabilitate six aging refineries, restore idle units and integrate the new Dos Bocas (Olmeca) refinery into the domestic fuel system. The objectives were explicit: lift utilization rates materially and reduce Mexico’s structural dependence on imported gasoline and diesel.

Related: U.S. Embargo Halts Venezuela Oil Shipments to Key Asian Buyers

By the end of 2025, the reset remained incomplete. Mexico’s six legacy refineries plus Dos Bocas have a combined nameplate capacity of around 1.98 million b/d. Yet actual refinery runs remain well below that ceiling. In November 2025, total throughput across the system stood at only around 1.14 million b/d (a 10-year high), underlining how far the system still operates from its theoretical capacity.

Even so, utilization has improved markedly over the past year. In November 2024, only one refinery saw utilization rates above 50%. By November 2025, five out of seven exceeded that threshold, with the strongest gains seen at the Tula, Cadereyta, Salina Cruz and Dos Bocas plants. Tula climbed to a 79% utilization rate, the highest in the country, while Dos Bocas surged from 17% to 61% in a single year. Cadereyta rose from 35% to 61%, and Salina Cruz improved from 44% to 60%, signalling that operational recovery is spreading beyond a single flagship site.

The recovery is evident in the output of refined products. Between November 2024 and November 2025, diesel production in the country jumped from 162,000 b/d to 280,700 b/d, a 42% year-on-year increase, while gasoline output rose from 307,000 b/d to 412,600 b/d, up 26%. Trade flows confirm the downstream shift. According to Kpler, average US diesel exports to Mexico fell from 187,000 b/d in 2023 to 118,000 b/d in 2025, a 37% reduction, while gasoline imports declined from 338,000 b/d to 309,000 b/d over the same period. These figures include supplies from PEMEX’s Deer Park refinery in Texas, which averaged about 30,000 b/d to Mexico in 2025, meaning the decline in third-party imports is even more pronounced.

Two main challenges continue to define the limits of the refining recovery. The first is financial. Years of neglect left refineries old, brittle and inefficient, and while the government has tried to curb fiscal exposure, there is still no visible path to sustaining the system without public support. According to Mexico’s Energy Sector Program 2025–2030, federal subsidies used to contain gasoline and diesel prices between 2018 and 2024 totaled MXN 833.4 billion (about US$46.3 billion) – a sum exceeding the cost of building Dos Bocas itself, and one that blurs the line between social policy and industrial investment.

The second constraint is energy security. Refining is an energy-intensive industrial process, and Mexico’s inland refineries have long been exposed to disruptions in electricity supply. The Tula, Salamanca, Cadereyta and Minatitlán refineries were designed decades ago around assumptions of stable power and hydrogen supply that no longer hold. Grid congestion, transmission outages and maintenance failures have repeatedly forced unplanned slowdowns or shutdowns at these sites. In practice, refinery runs have at times been curtailed not because of crude shortages or mechanical failures, but because of insufficient or unreliable electricity to operate compressors, pumps, hydrotreating units and safety systems.

Looking ahead, Mexico’s two most prominent refining assets will be the new Dos Bocas refinery, which is already delivering the largest gains in domestic production, and the Tula refinery, where long-delayed modernization could unlock the system’s next step-change. By November 2025, Dos Bocas was running at 61% utilization, processing 206,800 b/d, signalling that both of its 170,000 b/d distillation units have been operating already. Gasoline output, which weakened over the summer following repeated power outages, rebounded sharply in autumn, reaching 89,200 b/d in November.

At Tula (Mexico’s second-largest refinery and now its most heavily utilized one), a long-delayed coking unit, designed to convert low-value fuel oil from heavy Maya crude into gasoline, diesel, LPG and petroleum coke, is expected to lift fuel output by as much as 70% once fully operational. Yet the coker remains unfinished, nearly a decade behind schedule. While PEMEX previously targeted end-2025 for commissioning, current estimates push the coker’s launch toward late Q1 2026, with a naphtha hydrodesulfurization unit critical for low-sulfur gasoline also slated for completion in 2026 – large expectations for the clean products output in the months to come.

Mexico’s crude exports are falling, but not because oil has completely run out. They are falling because refineries are finally waking up. The recovery is real – visible in utilization rates, product output and shrinking imports – but it remains operationally fragile, fiscally heavy and dependent on infrastructure with little margin for error. Whether the shift proves durable will depend less on headline capacity than on power stability, maintenance discipline and whether long-delayed projects like Tula’s coker finally cross the finish line.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

- UK North Sea oil and gas endured its toughest year in decades in 2025, with investment pulled back sharply and offshore exploration falling to zero.

- The government’s decision to keep the 78% Energy Profits Levy in place until 2030 has deepened industry pessimism.

- Facing punitive taxes and shrinking activity, operators are turning to mergers and acquisitions to survive.

The once-thriving UK North Sea oil and gas province survived 2025, the most difficult year since the 1960s when hydrocarbons were first discovered in the basin.

Oil and gas production from the mature fields continued to decline last year, while uncertainties increased as industry expected changes to the UK government’s policy that places an enormous tax burden on operators without incentives or investment allowances. Companies active in the UK offshore oil and gas sector reduced investments and froze plans in the face of heightened uncertainty.

With the pullback in investment and the government’s reluctance to award new licenses, exploration in the UK North Sea plunged to an all-time low. Due to unpredictable fiscal policies, 2025 became the first year since 1960 without a single exploration well in Britain’s offshore, consultancy Wood Mackenzie has warned.

Windfall Tax Suppresses Investment

The UK oil and gas industry received clarity at the end of 2025 about the fiscal regime that it was awaiting for more than six months.

The government removed most of the uncertainty with the Autumn Budget in November. But it left the windfall tax unchanged as-is until 2030—contrary to the pleas and warnings from the sector that the total tax rate, including the windfall tax, of 78% and no incentives or allowances would essentially tax the industry and its supply chain to death.

In fact, the only certainty that the industry received was that the punitive tax, officially known as Energy Profits Levy (EPL), remains until the end of the decade. For 2025, the levy was triggered by oil prices above $76 per barrel or natural gas prices 59 pence per therm. Oil prices were mostly below the threshold, but gas prices have remained above 59p a therm, which triggers the 35% windfall tax on profits.

Last year was terrible for the UK North Sea. Industry sentiment is that the horrible years aren’t over and an accelerated decline in investment and exploration would kill the industry and increase Britain’s need for oil and gas imports, exposing one of Europe’s top economies even more to the volatile international oil, gas, and LNG markets.

The windfall tax, first introduced by a Conservative government at the height of the 2022 energy crisis and now extended under Labour, would wipe out all non-essential investment in the UK shelf, as it would compete with friendlier tax jurisdictions, according to WoodMac.

“The government turned down £50 billion of investment for the UK and the chance to protect the jobs and industries that keep this country running,” Offshore Energies UK chief executive, David Whitehouse, said in response to the decision to keep the windfall tax as-is.

“Instead, they’ve chosen a path that will see 1,000 jobs continue to be lost every month, more energy imports and a contagion across supply chains and our industrial heartlands,” Whitehouse added.

The Aberdeen & Grampian Chamber of Commerce said it’s “Lights out for North Sea oil and gas as Chancellor keeps windfall tax.”

The Chamber’s chief executive, Russell Borthwick, commented that instead of heeding advice from industry, “the UK Government has instead opted for a cliff-edge end to North Sea production and to tax the industry to death inside five years. Jobs will be lost in their thousands as a direct result of this government’s failure to act.”

The levy has prompted many companies to halt investment in the UK and move to cut workforce numbers in recent years.

The latest announcement came from one of the top independent producers, Harbour Energy, which last month said it expects to reduce employee numbers by another 100, on top of 600 jobs already eliminated since 2023.

Harbour Energy’s chief executive, Linda Cook, told the Financial Times at the end of December that the UK is “the worst of the fiscal environments among all the countries that [we] operate in.”

Due to the fiscal regime, the UK industry is forced to compete with other jurisdictions with “one arm tied behind its back”, Cook told FT.

Survival of the Fittest Mergers

In the unfriendly fiscal environments, operators in the UK North Sea are resorting to alternative solutions to boost profits and create value for shareholders. Mergers have become the most common of these solutions as the industry consolidates to cope with the punitive tax rate.

Last month, Harbour Energy announced an acquisition in the UK North Sea as the industry seeks to weather the crippling effects of the UK windfall tax.

“This transaction is an important step for Harbour in the UK North Sea, building on the action we’ve already taken to sustain our position in the basin given the ongoing fiscal and regulatory challenges,” said Scott Barr, Managing Director of Harbour’s UK Business Unit, commenting on the deal to buy Waldorf Energy Partners Ltd and Waldorf Production Ltd, currently in administration, for $170 million.

Harbour Energy became the latest operator in the UK to announce acquisitions, following the launch of the 50/50 joint venture of Shell and Equinor, which combined their offshore UK oil and gas operations in a new company, Adura. Earlier in December, French supermajor TotalEnergies said it would merge its upstream UK business with NEO NEXT to create the biggest independent oil and gas producer in Britain, NEO NEXT+.

Analysts expect the consolidation drive to continue, while the industry continues to call on the government to reform the fiscal regime.

“Restoring North Sea investment does not mean abandoning climate commitments; it is necessary to safeguard jobs, stabilise the economy, and maintain a bridge to a cleaner energy future,” UK’s energy and chemicals group Ineos, which has halted UK investments, said last month.

“How can businesses invest in that future if they are being driven to ruin?”

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

Mexico’s Crude Exports Slide as Refining Finally Reawakens

- Mexico’s crude exports have fallen from around 1.1 million b/d in 2020 to 503,000 b/d in December 2025 – the lowest level in the 21st century, while production has declined far less, signalling a shift toward domestic refining.

- A refining reset launched in 2019 has lifted utilization across much of the system, with five of seven refineries running above 50% by late 2025.

- Mexico’s refining gains are now visible in fuel output and trade, with diesel and gasoline production rising and US fuel imports easing, although the recovery remains uneven.

Mexico’s crude oil exports are shrinking fast – and this time the decline is not just a symptom of upstream exhaustion. Average crude exports have fallen from about 1.1 million b/d in 2020 to roughly 665,000 b/d in 2025, a near 40% drop. In December 2025, Mexico’s exports reached 503,000 b/d, marking a 21st century minimum. The drastic decrease is even starker for Maya, Mexico’s flagship heavy grade: December exports slid to 253,000 b/d, down 86% from 2020 levels. Ironically, the rapid decline in Mexico’s crude exports happens at the same time as the Trump administration seeks to gain control over Venezuela’s heavy sour barrels.

Production, by contrast, has eased far more modestly, declining by only around 100,000 b/d over the same period. That widening gap points to a structural shift: Mexico is exporting less crude largely because it needs more oil for its refineries at home. With roughly 60% of exports historically flowing to the US, the pullback has become increasingly visible in trade, signaling first good news from the industry to President Sheinbaum’s administration – the long-promised revival of domestic refining is beginning to show up in numbers.

The pivot traces back to 2019, when former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador launched a project to reset Mexico’s National Refining Systema (Sistema Nacional de Refinación, SNR). After decades of underinvestment and chronic underutilization, the strategy aimed to rehabilitate six aging refineries, restore idle units and integrate the new Dos Bocas (Olmeca) refinery into the domestic fuel system. The objectives were explicit: lift utilization rates materially and reduce Mexico’s structural dependence on imported gasoline and diesel.

Related: U.S. Embargo Halts Venezuela Oil Shipments to Key Asian Buyers

By the end of 2025, the reset remained incomplete. Mexico’s six legacy refineries plus Dos Bocas have a combined nameplate capacity of around 1.98 million b/d. Yet actual refinery runs remain well below that ceiling. In November 2025, total throughput across the system stood at only around 1.14 million b/d (a 10-year high), underlining how far the system still operates from its theoretical capacity.

Even so, utilization has improved markedly over the past year. In November 2024, only one refinery saw utilization rates above 50%. By November 2025, five out of seven exceeded that threshold, with the strongest gains seen at the Tula, Cadereyta, Salina Cruz and Dos Bocas plants. Tula climbed to a 79% utilization rate, the highest in the country, while Dos Bocas surged from 17% to 61% in a single year. Cadereyta rose from 35% to 61%, and Salina Cruz improved from 44% to 60%, signalling that operational recovery is spreading beyond a single flagship site.

The recovery is evident in the output of refined products. Between November 2024 and November 2025, diesel production in the country jumped from 162,000 b/d to 280,700 b/d, a 42% year-on-year increase, while gasoline output rose from 307,000 b/d to 412,600 b/d, up 26%. Trade flows confirm the downstream shift. According to Kpler, average US diesel exports to Mexico fell from 187,000 b/d in 2023 to 118,000 b/d in 2025, a 37% reduction, while gasoline imports declined from 338,000 b/d to 309,000 b/d over the same period. These figures include supplies from PEMEX’s Deer Park refinery in Texas, which averaged about 30,000 b/d to Mexico in 2025, meaning the decline in third-party imports is even more pronounced.

Two main challenges continue to define the limits of the refining recovery. The first is financial. Years of neglect left refineries old, brittle and inefficient, and while the government has tried to curb fiscal exposure, there is still no visible path to sustaining the system without public support. According to Mexico’s Energy Sector Program 2025–2030, federal subsidies used to contain gasoline and diesel prices between 2018 and 2024 totaled MXN 833.4 billion (about US$46.3 billion) – a sum exceeding the cost of building Dos Bocas itself, and one that blurs the line between social policy and industrial investment.

The second constraint is energy security. Refining is an energy-intensive industrial process, and Mexico’s inland refineries have long been exposed to disruptions in electricity supply. The Tula, Salamanca, Cadereyta and Minatitlán refineries were designed decades ago around assumptions of stable power and hydrogen supply that no longer hold. Grid congestion, transmission outages and maintenance failures have repeatedly forced unplanned slowdowns or shutdowns at these sites. In practice, refinery runs have at times been curtailed not because of crude shortages or mechanical failures, but because of insufficient or unreliable electricity to operate compressors, pumps, hydrotreating units and safety systems.

Looking ahead, Mexico’s two most prominent refining assets will be the new Dos Bocas refinery, which is already delivering the largest gains in domestic production, and the Tula refinery, where long-delayed modernization could unlock the system’s next step-change. By November 2025, Dos Bocas was running at 61% utilization, processing 206,800 b/d, signalling that both of its 170,000 b/d distillation units have been operating already. Gasoline output, which weakened over the summer following repeated power outages, rebounded sharply in autumn, reaching 89,200 b/d in November.

At Tula (Mexico’s second-largest refinery and now its most heavily utilized one), a long-delayed coking unit, designed to convert low-value fuel oil from heavy Maya crude into gasoline, diesel, LPG and petroleum coke, is expected to lift fuel output by as much as 70% once fully operational. Yet the coker remains unfinished, nearly a decade behind schedule. While PEMEX previously targeted end-2025 for commissioning, current estimates push the coker’s launch toward late Q1 2026, with a naphtha hydrodesulfurization unit critical for low-sulfur gasoline also slated for completion in 2026 – large expectations for the clean products output in the months to come.

Mexico’s crude exports are falling, but not because oil has completely run out. They are falling because refineries are finally waking up. The recovery is real – visible in utilization rates, product output and shrinking imports – but it remains operationally fragile, fiscally heavy and dependent on infrastructure with little margin for error. Whether the shift proves durable will depend less on headline capacity than on power stability, maintenance discipline and whether long-delayed projects like Tula’s coker finally cross the finish line.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

The Libya Oil Story No One Is Pricing In Yet

- More than 40 companies have registered for Libya’s first licensing round since 2011, prompting the National Oil Corporation to target 2 million bpd by 2028.

- Libya holds Africa’s largest proven reserves (48 billion barrels) and has lifted output back toward 1.4 million bpd.

- Firms such as TotalEnergies, ConocoPhillips, Eni, Repsol, and OMV are betting that deeper on-the-ground presence can stabilize the political framework.

With more than 40 companies having now registered their interest in Libya’s first oil field licensing round since the removal of Muammar Gaddafi as leader in 2011, the National Oil Corporation (NOC) is confident it can lift oil production to 2 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2028, according to the latest statements from the organisation. The expressions of interest in the 22 offshore and onshore blocks to be licensed follow last year’s agreements between the NOC and Great Britain’s Shell and BP to assess Libya’s exploration opportunities. Shortly after that, U.S. supermajor ExxonMobil inked a deal covering technical studies on a cluster of offshore blocks, while Chevron has also confirmed that it is planning a return to the country, having left in 2010. The key question for the oil markets, though, is does this influx of Western firms signal a genuinely more stable political backdrop in Libya that will allow it to finally make good on its oil potential?

There is certainly plenty of this to work with, as Libya remains the holder of Africa’s largest proved crude oil reserves, of 48 billion barrels. Before the removal of Gaddafi and the civil war that ensued, the country was producing around 1.65 million bpd of mostly high-quality light, sweet crude oil, notably the Es Sider and Sharara export crudes that are particularly in demand in the Mediterranean and Northwest Europe for their gasoline and middle distillate yields. This had been on a rising production trajectory, up from about 1.4 million bpd in 2000, albeit well below the peak levels of more than 3 million bpd achieved in the late 1960s, analysed in my latest book on the new global oil market order. That said, NOC plans were in place before 2011 to roll out enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques to increase crude oil production at maturing oil fields and the NOC’s predictions of being able to increase capacity by around 775,000 bpd through EOR at existing oil fields looked well-founded. Around 80% of all of Libya’s currently discovered recoverable reserves are located in the Sirte basin, which also accounts for most of the country’s oil production capacity, according to the Energy Information Administration. However, in the depths of the civil war, crude oil output fell to around 20,000 bpd, and although it has recovered now to just under 1.4 million bpd -- the highest level since mid-2013 -- various politically-motivated shutdowns in recent years have pushed this down to just over 500,000 bpd for prolonged periods.

The problem for the Western firms now re-entering the country is that the core reasons behind these shutdowns have not been dealt with in any meaningful way. More specifically, at the time of signing the 18 September 2020 agreement that ended an economically devastating series of oil blockades across Libya at that time, Commander of the rebel Libyan National Army (LNA) General Khalifa Haftar made it clear that peace would be dependent on key objectives being met. Tripoli’s U.N.-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), and fellow signatory to the deal, Ahmed Maiteeq, agreed to such measures that would address how the country’s oil revenues would be distributed over the long term and how the country’s perilous financial position might be stabilised in the short term. At that point, the blockade from 18 January to 18 September had cost the country at least US$9.8 billion in lost hydrocarbons revenues. Key to this tentative agreement was the formation of a joint technical committee, which would – according to the official statement: “Oversee oil revenues and ensure the fair distribution of resources… and control the implementation of the terms of the agreement during the next three months, provided that its work is evaluated at the end of the 2020 and a plan is defined for the next year.” In order to address the fact that the then-GNA effectively held sway over the NOC and, by extension, the Central Bank of Libya (in which the revenues are physically held), the committee would also “prepare a unified budget that meets the needs of each party… and the reconciliation of any dispute over budget allocations… and will require the Central Bank [in Tripoli] to cover the monthly or quarterly payments approved in the budget without any delay, and as soon as the joint technical committee requests the transfer.” None of these measures have since been put into place, which leaves fundamental flashpoints over the country’s core revenue stream remaining.

Instead, Washington and London’s broad strategy in Libya appears to be that Western firms should re-establish their presence on the ground across multiple sites in Libya and, through this presence and ongoing investment across the country, the resulting greater political leverage can be used to finally put such mechanisms for peace in place. It is a similar idea to that currently being rolled out in Syria, whose previous longtime leader (Bashar al-Assad) was also removed by the West among a backdrop of intense factionalism -- and widespread Russian interference -- across the country as well. That said, the West’s presence in Libya never retreated as much as it did in Syria. Back in 2021, when the NOC first flagged serious plans to significantly boost its oil output, at that point up to 1.6 million bpd and then perhaps to 2 million bpd, French oil giant Total (now TotalEnergies) agreed to continue with its efforts to increase oil production from the giant Waha, Sharara, Mabruk and Al Jurf oil fields by at least 175,000 bpd and to make the development of the Waha-concession North Gialo and NC-98 oil fields a priority, according to the NOC. The Waha concessions – in which Total took a minority stake in 2019 – have the capacity to produce at least 350,000 bpd together, according to the NOC, which added that Total would also “contribute to the maintenance of decaying equipment and crude oil transport lines that need replacing.”

Following these developments, NOC subsidiary Waha Oil announced that it has increased crude oil production by 20% since 2024 by dint of intensive maintenance programs, reopening shut-in wells and drilling new ones. Recent NOC comments highlighted similar initiatives as being the catalyst for the latest uptick in output across the country, together with new discoveries by its subsidiary Agoco and Algeria's Sonatrach in the Ghadames Basin and Austria's OMV in the Sirte Basin. These efforts are part of the newly re-energised ‘Strategic Programs Office’ (SPO), which was focused on boosting production to 1.6 million bpd within a year, before rising political tensions last year delayed such initiatives. The SPO’s potential success also depends in part on the outcome of the current licensing round, as it needs around US$3-4 billion to reach the initial 2026/27 1.6 million bpd production target. That said, the 22 offshore and onshore blocks to be licensed include major sites in the Sirte, Murzuq, and Ghadamis basins as well as in the offshore Mediterranean region. In addition the firms already mentioned, U.S. supermajor ConocoPhillips has voiced its interest in expanding its operations in Libya beyond its current running of the Waha concession. From Europe, interest may well include Italy’s Eni, Spain’s Repsol, and Austria’s OMV.

Meanwhile, Great Britain’s BP said last July that it had signed a memorandum of understanding to evaluate options for redeveloping the giant Sarir and Messla onshore fields in the Sirte basin, and to assess potential unconventional oil and gas development. The firm’s executive vice president for gas and low carbon, William Lin, stated that the agreement, “reflects our strong interest in deepening our partnership with NOC and supporting the future of Libya’s energy sector.” And given that Libyan oil production is exempt from OPEC+ quotas -- and is rarely priced in by markets until after the fact -- any major swing in output could once again tip the balance in a tight market, as it has done before.

By Simon Watkins for Oilprice.com

- More than 40 companies have registered for Libya’s first licensing round since 2011, prompting the National Oil Corporation to target 2 million bpd by 2028.

- Libya holds Africa’s largest proven reserves (48 billion barrels) and has lifted output back toward 1.4 million bpd.

- Firms such as TotalEnergies, ConocoPhillips, Eni, Repsol, and OMV are betting that deeper on-the-ground presence can stabilize the political framework.

With more than 40 companies having now registered their interest in Libya’s first oil field licensing round since the removal of Muammar Gaddafi as leader in 2011, the National Oil Corporation (NOC) is confident it can lift oil production to 2 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2028, according to the latest statements from the organisation. The expressions of interest in the 22 offshore and onshore blocks to be licensed follow last year’s agreements between the NOC and Great Britain’s Shell and BP to assess Libya’s exploration opportunities. Shortly after that, U.S. supermajor ExxonMobil inked a deal covering technical studies on a cluster of offshore blocks, while Chevron has also confirmed that it is planning a return to the country, having left in 2010. The key question for the oil markets, though, is does this influx of Western firms signal a genuinely more stable political backdrop in Libya that will allow it to finally make good on its oil potential?

There is certainly plenty of this to work with, as Libya remains the holder of Africa’s largest proved crude oil reserves, of 48 billion barrels. Before the removal of Gaddafi and the civil war that ensued, the country was producing around 1.65 million bpd of mostly high-quality light, sweet crude oil, notably the Es Sider and Sharara export crudes that are particularly in demand in the Mediterranean and Northwest Europe for their gasoline and middle distillate yields. This had been on a rising production trajectory, up from about 1.4 million bpd in 2000, albeit well below the peak levels of more than 3 million bpd achieved in the late 1960s, analysed in my latest book on the new global oil market order. That said, NOC plans were in place before 2011 to roll out enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques to increase crude oil production at maturing oil fields and the NOC’s predictions of being able to increase capacity by around 775,000 bpd through EOR at existing oil fields looked well-founded. Around 80% of all of Libya’s currently discovered recoverable reserves are located in the Sirte basin, which also accounts for most of the country’s oil production capacity, according to the Energy Information Administration. However, in the depths of the civil war, crude oil output fell to around 20,000 bpd, and although it has recovered now to just under 1.4 million bpd -- the highest level since mid-2013 -- various politically-motivated shutdowns in recent years have pushed this down to just over 500,000 bpd for prolonged periods.

The problem for the Western firms now re-entering the country is that the core reasons behind these shutdowns have not been dealt with in any meaningful way. More specifically, at the time of signing the 18 September 2020 agreement that ended an economically devastating series of oil blockades across Libya at that time, Commander of the rebel Libyan National Army (LNA) General Khalifa Haftar made it clear that peace would be dependent on key objectives being met. Tripoli’s U.N.-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), and fellow signatory to the deal, Ahmed Maiteeq, agreed to such measures that would address how the country’s oil revenues would be distributed over the long term and how the country’s perilous financial position might be stabilised in the short term. At that point, the blockade from 18 January to 18 September had cost the country at least US$9.8 billion in lost hydrocarbons revenues. Key to this tentative agreement was the formation of a joint technical committee, which would – according to the official statement: “Oversee oil revenues and ensure the fair distribution of resources… and control the implementation of the terms of the agreement during the next three months, provided that its work is evaluated at the end of the 2020 and a plan is defined for the next year.” In order to address the fact that the then-GNA effectively held sway over the NOC and, by extension, the Central Bank of Libya (in which the revenues are physically held), the committee would also “prepare a unified budget that meets the needs of each party… and the reconciliation of any dispute over budget allocations… and will require the Central Bank [in Tripoli] to cover the monthly or quarterly payments approved in the budget without any delay, and as soon as the joint technical committee requests the transfer.” None of these measures have since been put into place, which leaves fundamental flashpoints over the country’s core revenue stream remaining.

Instead, Washington and London’s broad strategy in Libya appears to be that Western firms should re-establish their presence on the ground across multiple sites in Libya and, through this presence and ongoing investment across the country, the resulting greater political leverage can be used to finally put such mechanisms for peace in place. It is a similar idea to that currently being rolled out in Syria, whose previous longtime leader (Bashar al-Assad) was also removed by the West among a backdrop of intense factionalism -- and widespread Russian interference -- across the country as well. That said, the West’s presence in Libya never retreated as much as it did in Syria. Back in 2021, when the NOC first flagged serious plans to significantly boost its oil output, at that point up to 1.6 million bpd and then perhaps to 2 million bpd, French oil giant Total (now TotalEnergies) agreed to continue with its efforts to increase oil production from the giant Waha, Sharara, Mabruk and Al Jurf oil fields by at least 175,000 bpd and to make the development of the Waha-concession North Gialo and NC-98 oil fields a priority, according to the NOC. The Waha concessions – in which Total took a minority stake in 2019 – have the capacity to produce at least 350,000 bpd together, according to the NOC, which added that Total would also “contribute to the maintenance of decaying equipment and crude oil transport lines that need replacing.”

Following these developments, NOC subsidiary Waha Oil announced that it has increased crude oil production by 20% since 2024 by dint of intensive maintenance programs, reopening shut-in wells and drilling new ones. Recent NOC comments highlighted similar initiatives as being the catalyst for the latest uptick in output across the country, together with new discoveries by its subsidiary Agoco and Algeria's Sonatrach in the Ghadames Basin and Austria's OMV in the Sirte Basin. These efforts are part of the newly re-energised ‘Strategic Programs Office’ (SPO), which was focused on boosting production to 1.6 million bpd within a year, before rising political tensions last year delayed such initiatives. The SPO’s potential success also depends in part on the outcome of the current licensing round, as it needs around US$3-4 billion to reach the initial 2026/27 1.6 million bpd production target. That said, the 22 offshore and onshore blocks to be licensed include major sites in the Sirte, Murzuq, and Ghadamis basins as well as in the offshore Mediterranean region. In addition the firms already mentioned, U.S. supermajor ConocoPhillips has voiced its interest in expanding its operations in Libya beyond its current running of the Waha concession. From Europe, interest may well include Italy’s Eni, Spain’s Repsol, and Austria’s OMV.

Meanwhile, Great Britain’s BP said last July that it had signed a memorandum of understanding to evaluate options for redeveloping the giant Sarir and Messla onshore fields in the Sirte basin, and to assess potential unconventional oil and gas development. The firm’s executive vice president for gas and low carbon, William Lin, stated that the agreement, “reflects our strong interest in deepening our partnership with NOC and supporting the future of Libya’s energy sector.” And given that Libyan oil production is exempt from OPEC+ quotas -- and is rarely priced in by markets until after the fact -- any major swing in output could once again tip the balance in a tight market, as it has done before.

By Simon Watkins for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment