Venezuela’s economy and the transition to socialism

First published at Ang Masa Para sa Sosyalismo.

The United States has unleashed a frontal assault not only on Venezuela, but on all of Latin America—and on the very idea of sovereignty itself, which is a threat to all countries of the Global South. The attack on Venezuela is a central front in a wider imperial offensive to reimpose U.S. domination over the region. Under the Trump administration, Washington has openly revived the 202-year-old colonial Monroe Doctrine, cynically updating it for the twenty-first century and arrogantly rebranding it as the “Donroe Doctrine,” a declaration of imperial entitlement over the peoples, resources, and futures of Latin America.

By attacking Venezuela, the U.S. empire hopes to accomplish several goals:

- Impose U.S. hegemony in Latin America (from the Monroe Doctrine to the Donroe Doctrine).

- Exploit Venezuela’s natural resources (oil, gas, critical minerals, and rare earth elements), as part of an attempt to build a new supply chain in the western hemisphere.

- Cut off Latin America’s ties with China (as well as with Russia and Iran).

- Threaten other left-wing governments in the region (primarily Cuba and Nicaragua, but also Brazil and Colombia).

- Destroy the project of regional integration in Latin America and the Caribbean (in organizations like the ALBA and CELAC).

- Sabotage Global South unity (given Venezuela’s support for Palestine, Iran, African liberation struggles, etc.).

An understanding of the economic crisis in Venezuela is important to counter this naked imperialist aggression. This article presents a left political-economy analysis of the Venezuelan economic crisis, integrating the work of economist Michael Roberts, CounterPunch, Jacobin and Monthly Review contributors. It argues that Venezuela’s economic crisis reflects the interaction of rentier capitalism, external monetary constraint, and imperialist sanctions rather than the failure of socialism.

1. Rentier Capitalism and Structural Limits

Venezuela’s core structural weakness lies in its rentier capitalist formation, in which oil income takes the form of ground rent rather than surplus value generated through diversified domestic production (Roberts, 2024, 2026). High oil prices enabled redistribution without transforming the productive base, masking low productivity, weak profitability, and limited accumulation outside hydrocarbons. This diagnosis aligns with Latin American structuralist economics, which holds that demand expansion in peripheral economies with weak industrial capacity leads to import dependence and balance-of-payments pressure rather than endogenous growth.

Roberts (2026) emphasizes that even during periods of oil recovery, Venezuela remains trapped in price-dependent rent extraction: “the tragedy of Venezuela is that everything depended on the oil price; there was little or no development of the non‑oil sectors, which anyway were in the hands of private companies. There was no independent national plan of investment controlled by the state.”

Oil output normalization does not resolve the underlying absence of value-creating accumulation, leaving the economy structurally vulnerable to external shocks and coercion.

2. The Chávez Years: Social Gains Without Class Expropriation

Left analyses associated with CounterPunch and related outlets emphasize the historically significant social gains achieved during the Chávez years, including sharp poverty reduction, expanded healthcare access, education, and food security. These advances were real and transformative for the popular classes. According to Pete Dolack (CounterPunch, 2019): “There are also the social programs known as “missions” that are based on the direct participation of the beneficiaries. Begun in 2003, there are more than two dozen missions that seek to solve a wide array of social problems. Given the corruption and inertia of the state bureaucracy, and the unwillingness of many professionals to provide services to poor neighborhoods, the missions were established to provide services directly while enabling participants to shape the programs. Much government money was poured into these programs, thanks to the then high price of oil, which in turn enabled the Chávez government to fund them.”

Roberts reinforces the argument that redistribution rested on oil rents rather than a reorganization of production relations. The domestic bourgeoisie was not expropriated as a class, private banking remained largely intact, and nationalizations often lacked workers’ control, limiting deeper structural transformation.

3. The Communes: Localized Economic Organization Under Sanctions

During the Chávez period, the Venezuelan government promoted the establishment of communes as part of the Bolivarian vision of participatory socialism. These are legally recognized local collective organizations that coordinate production, social services, and local governance, particularly in poor neighborhoods and rural areas. Under the weight of U.S. sanctions and economic blockade, communes have become vital to everyday survival, distributing food and organizing essential services where the state alone cannot reach. According to Peter Lackowski (CounterPunch, 2026): “The years 2016 through 2021 were a time of intense hunger and death after President Obama acted to cut off food and medicine imports. The communes responded with a surge in production that has contributed to Venezuela’s near-complete self-sufficiency in food today.”

Yet they cannot substitute for national-scale industrial and infrastructure investment, which is necessary for structural transformation. In effect, communes function as a buffer system, redistributing resources and enabling survival under externally imposed economic coercion, while fostering a limited form of participatory economic practice.

In sum, communes represent a partial counterweight to capitalist market pressures exacerbated by sanctions, but they do not, in isolation, overcome the systemic reliance on oil rents or transform Venezuela’s broader production relations. Their effectiveness is amplified in regions where local engagement is high but remains tightly constrained by national and international economic forces.

Bureaucratic state ownership, however, left critiques argue, that state ownership without workers’ control or democratic planning does not abolish capitalist relations; it often reproduces bureaucratic management and inefficiency, especially where production remains dependent on oil rents rather than socialized accumulation. (Roberts, 2024)

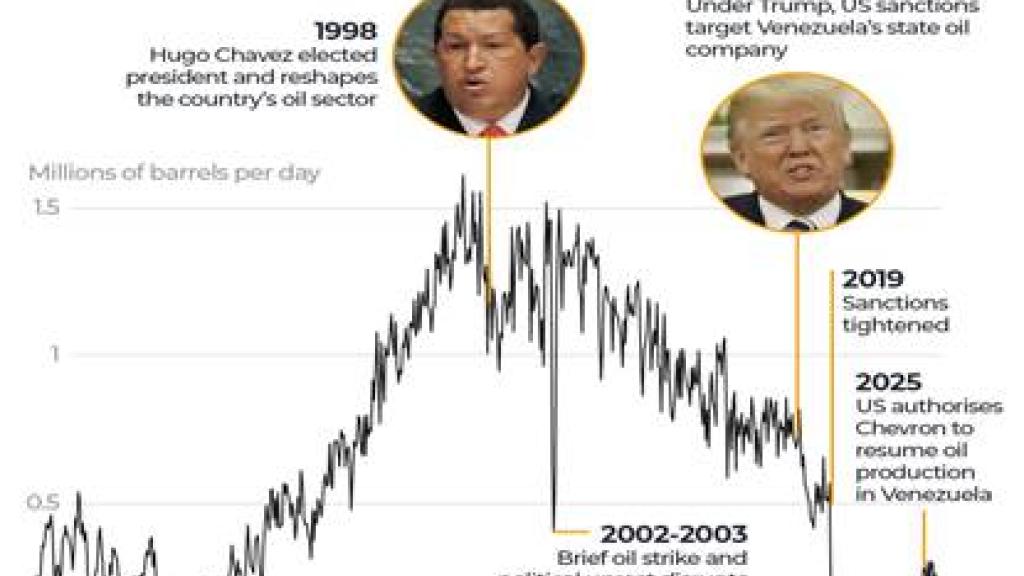

4. Sanctions as Imperialist Economic Warfare

There is broad consensus that U.S. sanctions constitute coercive economic warfare and collective punishment rather than neutral policy instruments. Financial sanctions imposed from 2017 onward prohibited new Venezuelan government borrowing, blocked debt restructuring, and severed access to international credit and trade finance, sharply accelerating economic collapse: “Most immediately, they prevented a debt restructuring that would be necessary to resolve Venezuela’s balance of payments crisis. The sanctions also prevented the government from pursuing an ERBS program because a peg to the dollar would require access to the dollar-based financial system, which the sanctions have cut off as much as possible. The whole idea of restoring confidence in the domestic currency while stabilizing the exchange rate would seem impossible when a foreign power is cutting off as much of the country’s dollar revenue as it can, freezing and confiscating international assets, and, as the Trump administration has done for nearly two years, pledging to do much more of these things — not to mention threatening to take military action. Thus, one of the most important impacts of the sanctions, in terms of its effects on human life and health, is to lock Venezuela into a downward economic spiral.” (Weisbrot & Sachs, 2019).

Sanctions froze billions of dollars in Venezuelan state assets held abroad, including foreign exchange reserves and the U.S.-based subsidiary CITGO, while secondary sanctions intimidated banks, insurers, and shipping firms from engaging in even humanitarian transactions. The result was acute import compression, particularly of food, medicine, fuel, and industrial inputs.

Restrictions on Venezuela’s oil exports and payments systems forced crude sales at steep discounts and drastically reduced usable foreign exchange. These measures were explicitly aimed at controlling Venezuelan oil reserves, particularly in the Orinoco Belt, and reasserting U.S. hegemony in Latin America. Sanctions, blockades, and coup attempts thus form an integrated imperial strategy of rent extraction rather than discrete policy errors.

5. Humanitarian and Class Impacts of Sanctions

Empirical evidence demonstrates that sanctions had severe and measurable humanitarian consequences. Weisbrot and Sachs (2019) estimate that sanctions contributed to tens of thousands of excess deaths by sharply reducing imports of food, medicine, and medical equipment. Caloric intake declined, disease prevalence increased, and the public healthcare system experienced acute shortages due to blocked financial transactions. Marcetic (2019) provides vivid quantification and argumentation about how sanctions inflict human suffering and exacerbate crises. (Branko Marcetic, 2019)

Sanctions also functioned as a class weapon. Wage-dependent populations bore the brunt of inflation, shortages, and service collapse, while holders of foreign currency and capital adapted through dollarization, arbitrage, and offshore accumulation. Sanctions therefore redistributed income upward while politically disciplining the Venezuelan working class: “The impact of sanctions on Venezuela has been severe and widespread, disproportionately affecting the poor and those dependent on wages and government services. While the wealthy and those with access to foreign currency have been largely able to avoid the worst effects, wage earners have suffered from shortages, inflation, and declining real incomes. In this sense, sanctions act as a tool of class oppression, redistributing resources upward and disciplining the popular classes.” (Weisbrot & Sachs, 2019)

6. Inflation, External Constraint, and Distributional Conflict

Sanctions-induced dollar shortages transformed inflation into a mechanism of class redistribution, eroding real wages and public-sector incomes while protecting profits and wealth denominated in foreign currency (Roberts, 2026).

Inflation thus emerged not from fiscal excess but from externally imposed scarcity interacting with a rentier production structure. The loss of oil export revenues and access to international payment systems sharply constrained imports of food, medicine, fuel, and industrial inputs.

From a balance-of-payments perspective, Venezuela’s macroeconomic instability was driven by a binding external constraint. Growth and stabilization were limited by access to foreign exchange. Multiple exchange-rate regimes were rational responses to scarcity, designed to prioritize essential imports and social programs, but under conditions of capital flight, sanctions, and institutional erosion they generated arbitrage, corruption, and parallel markets. Even during periods of oil-price recovery, sanctions sharply reduced net export earnings, reinforcing the foreign-exchange constraint and undermining policy effectiveness: As Roberts points out “Although oil prices began recovering in 2017 and output stabilized in other oil producers, it did not in Venezuela – because that was the year that sanctions by the US and other countries were imposed.” (Roberts, 2024).

Venezuela lacked effective monetary sovereignty. Although it issued its own currency, essential goods and capital inputs required access to foreign exchange overwhelmingly generated by oil exports. Sanctions reducing export earnings that translate directly into shortages and economic instability, while inflation followed the loss of foreign exchange rather than excessive money creation. Sanctions strangled access to dollars, making stabilization impossible.

7. Profitability, Capital Strike, and Dual Economic Structures

Beyond macroeconomic instability, Venezuela’s prolonged stagnation reflects chronically low profitability and weak accumulation outside the hydrocarbons sector. Roberts links this to the failure to transform production relations and diversify industrial capacity. Sanctions deepened this structural weakness by destroying investment expectations, cutting off trade finance and insurance, and enforcing a politically mediated capital strike against both state-led and private investment.

Post-Keynesian theory complements this analysis by emphasizing how uncertainty, blocked finance, and collapsing expectations suppress long-term investment even when the state seeks to coordinate accumulation. Under sanctions, profitability calculations were reshaped not by productive efficiency but by access to foreign currency, import channels, and informal networks.

Informal dollarization partially stabilized circulation and trade but produced a segmented dual economy: a dollar-based service, commerce, and import sector alongside a precarious bolívar wage economy dependent on collapsing real incomes. This dual-circuit accumulation pattern, characteristic of peripheral economies under external constraint, entrenched inequality and weakened collective labor power. Wage earners absorbed the costs of adjustment through inflation and deteriorating public services, while holders of dollars and mobile capital adapted through arbitrage, offshore accumulation, and selective market integration (Roberts, 2026).

Taken together, these dynamics show that Venezuela’s crisis was not simply one of mismanagement or policy error. It was the outcome of structural dependence, sanctions-induced external strangulation, and class struggle over distribution under conditions of scarcity. Inflation, dollarization, and capital flight functioned as mechanisms of upward redistribution and political discipline, reinforcing capitalist social relations rather than transcending them.

As sociologist Malfred Gerig argues, Venezuela’s crisis cannot be reduced either to policy error or sanctions alone, but to their interaction with deep structural contradictions: “This is not a question of bad economic policy, but of deeply serious structural contradictions… The sanctions were mounted on these two factors – poor management of economic policy and a very serious crisis – thus creating a perfect storm… dispossession, social marginalization, deterioration of production conditions, etc.” (Gerig, Jacobin Revista)

8. Recent Growth Trends (2024–2025)

Despite long-term structural and imperial pressures, Venezuela recorded positive growth in 2024 and 2025, driven primarily by partial oil-sector recovery and sanctions evasion. Official figures report growth above 9 percent in 2024, while IMF and external estimates remain more modest.

Roberts (2026) cautions that this rebound reflects price effects and output normalization rather than a transformation of productivity, living standards, or class relations. From a heterodox perspective, Venezuela exhibits stabilization without development.

Conclusion

Sanctions imposed by the United States and supported by other imperialist powers functioned as a form of economic warfare, tightening external constraints, collapsing foreign-exchange earnings, and redistributing income upward. These measures were not reactions to policy failure but instruments of discipline designed to block sovereign development paths outside imperialist control.

The Venezuelan experience demonstrates that socialism cannot be constructed through rentier capitalism, even when resource rents are deployed for progressive redistribution. Oil revenues enabled historically significant social gains, but they did not dissolve capitalist production relations or overcome structural dependence on external markets. As long as accumulation remained grounded in hydrocarbon rents rather than transformed productive relations, the Bolivarian process remained vulnerable to external shocks, capital flight, and imperialist coercion.

State ownership alone is insufficient. Without workers’ control, democratic planning, and effective accountability within state enterprises, nationalization reproduced bureaucratic inefficiency and elite privilege. Under sanctions, emergency centralisation and a lack of transparency further entrenched bureaucratic power, weakening popular participation. Socialist transition requires not merely public ownership, but the collective control of production by the working class.

Importantly, many of these contradictions were recognized by Hugo Chávez himself. Chávez repeatedly warned of the dangers of bureaucratization, and insufficient transformation of production relations. The persistence of bureaucratic privileges within the state apparatus reflected not a lack of awareness but the unresolved balance of class forces within Venezuelan society and the international system.

The Venezuelan case also highlights the centrality of political struggle and mass mobilization. Electoral victories and redistributive policies proved insufficient without sustained grassroots organization capable of enforcing accountability, expanding workers’ power, and resisting bureaucratic consolidation. Campaigns, popular education, and organized class struggle remain decisive for any socialist project under siege.

The experience invites comparison with Cuba, which—despite severe limitations under an economic blockade — demonstrates the strategic importance of breaking landlord and capitalist power early, maintaining mass political organization, and prioritizing socialist planning over rent distribution. Cuba’s trajectory shows that survival under sanctions is possible, but only through deep social mobilization, disciplined organization, and the subordination of bureaucratic privilege to popular control.

In sum, socialism cannot be built without dismantling rent dependence, confronting bureaucratic privilege, and placing workers’ democratic control at the center of economic life—especially within a world system structured to punish any challenge to imperialist capitalist hegemony. Venezuela’s crisis must therefore be understood as part of a broader historical problem: the attempt to transition toward socialism within a hostile global capitalist system that possesses both the economic and military power to crush revolutionary projects. Economic sanctions and blockades are central weapons in this imperialist arsenal, designed precisely to suffocate such transitions. Economic warfare aimed at strangling revolutionary processes is often the primary form of imperialist attack, preceding—and in some cases replacing—direct military intervention. Campaigning against imperialist sanctions and blockades must therefore be a central task of the international solidarity movement, even before open military aggression erupts.

References

Ben Norton. (2026). Donroe Doctrine: Trump attack on Venezuela is part of imperial plan to impose U.S. hegemony in Latin America. https://mronline.org/2026/01/06/donroe-doctrine-trump-attack-on-venezuela-is-part-of-imperial-plan-to-impose-u-s-hegemony-in-latin-america/

Roberts, M. (2024). Venezuela: The end game? The Next Recession. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2024/07/27/venezuela-the-end-game/

Roberts, M. (2026). Venezuela and oil. The Next Recession. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2026/01/05/venezuela-and-oil/

Pete Dolack. (2019). Sorting Through the Lies About Venezuela – CounterPunch.org

Peter Lackowski. (2026) Venezuela’s Communes: Socialism of the Twenty-First Century. https://www.counterpunch.org/2026/01/03/venezuelas-communes-socialism-of-the-twenty-first-century/

Weisbrot, M., & Sachs, J. (2019). Economic sanctions as collective punishment: The case of Venezuela. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://mronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/venezuela-sanctions-2019-04-1.pdf

Branko Marcetic (2019). Sanctions Are Murder. https://jacobin.com/2019/05/venezuela-sanctions-trump-intervention Sanctions Are Murder

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Venezuela country profile. https://www.imf.org/en/countries/ven

CounterPunch. (2025). The U.S. war on China, Venezuela, and the international left. https://www.counterpunch.org/2025/11/11/the-u-s-war-on-china-venezuela-and-the-international-left/

Monthly Review / MR Online. (2019–2020). Venezuela sanctions dossiers and CEPR reports. https://mronline.org

Pete Dolack. (2019). Sorting through the lies about Venezuela. https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/02/01/sorting-through-the-lies-about-venezuela/

Malfred Gerig. (2024). La larga depresión venezolana. https://jacobinlat.com/2024/11/la-larga-depresion-venezolana/ (Jacobin Revista)

MR Online. (2020). Economic sanctions as collective punishment: The case of Venezuela (Weisbrot & Sachs). https://mronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/venezuela-sanctions-2019-04-1.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment