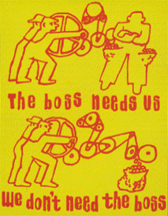

To paraphrase Proudhon; Intellectual Property Is Theft!

Generals, Gadgets, and Guerrillas

The age of the media gadget is here, with Apple steamrolling the big distributors. But when consumers have the power to get content anywhere, anytime, for free, even Steve Jobs should be worried.

by Michael Wolff

Vanity Fair December 2007

A marketer would call this empowerment—as a consumer you’re getting the service you want at the time and place you want it, more cheaply than you could have ever hoped to get it, as well as, often, critical help in stealing the particular service or tune.Men with big jobs in big corporations have a word for this anywhere-anytime (let-us-help-you-steal-it) breakdown in distribution norms: anarchy.

They’ve, in fact, had laws passed to inhibit it.But more and more, as gadgetism explodes, as it undermines every fixed notion of who delivers what to whom, as the big men with big jobs try to develop their gadget strategies, it’s comedy too. Everybody in charge of distribution channels is running around like a chicken with its head cut off. People at music companies, television networks, movie studios, cable providers, phone companies, and satellite systems are all trying, vainly so far, to figure out their place in a gadget-driven world, and are, mostly, looking like fools. NBC, in a huff, recently pulled its stuff from Apple’s iTunes downloading service because it believes its shows are worth more than $1.99 apiece. Then, in an about-face, the network announced it will give away its shows for free—figuring that somehow they’ll rig it up, those technological geniuses, so that after you download a show to your gadget and you see it once or twice, the show will dissolve or explode, or some such.

The full development of capital, therefore, takes place -- or capital has posited the mode of production corresponding to it -- only when the means of labour has not only taken the economic form of fixed capital, but has also been suspended in its immediate form, and when fixed capital appears as a machine within the production process, opposite labour; and the entire production process appears as not subsumed under the direct skillfulness of the worker, but rather as the technological application of science. [It is,] hence, the tendency of capital to give production a scientific character; direct labour [is] reduced to a mere moment of this process. As with the transformation of value into capital, so does it appear in the further development of capital, that it presupposes a certain given historical development of the productive forces on one side -- science too [is] among these productive forces -- and, on the other, drives and forces them further onwards.

To the degree that labour time -- the mere quantity of labour -- is posited by capital as the sole determinant element, to that degree does direct labour and its quantity disappear as the determinant principle of production -- of the creation of use values -- and is reduced both quantitatively, to a smaller proportion, and qualitatively, as an, of course, indispensable but subordinate moment, compared to general scientific labour, technological application of natural sciences, on one side, and to the general productive force arising from social combination [Gliederung] in total production on the other side -- a combination which appears as a natural fruit of social labour (although it is a historic product). Capital thus works towards its own dissolution as the form dominating production.

Marx Grundrisse Ch. 13

Beginning with cybernetics, and the resulting evolution of machine automation into personal computers, the internet, the resulting software and gadgets are all a glimpse of the shape of things to come; from each according to their abilities to each according to their needs.

Notes:

Raoul Victor

Free Software and Market Relations

But the logic of free software situates itself outside of exchange itself. When someone "takes" free software off the Internet, even if its production required millions of hours of labor, there is nothing given in exchange. One takes without furnishing any counterpart. The software furnished is not exactly "given," in the classic sense of the term, since the provider still has it after the taker has helped himself. (In this sense, the term of "economy of the gift" that certain people use apropos free software is incorrect.) There is indeed the transmission of a good, but with neither loss of possession nor counter-party. The foundation of capitalism, exchange, is absent. In this sense already, free software has an intrinsically anti-capitalist, potentially revolutionary nature.

But it does not suffice to be "anti-capitalist" to be revolutionary historically, as shown by the nostalgic anti-capitalist thought of a less dehumanized past. If free software possesses a revolutionary nature, that is also because its method rests on the concrete will to liberate the powers contained in the new techniques of information and communication. This method is the result of the simple acknowledgment on t he part of several universities that certain aspects of market relations gravely impeded their utilization. If this happens with electronic techniques and not with other techniques of production, that is not only because the scientific ethic contains non-market aspects but also because, and above all, in this domain it is very easy, and costs nothing, to ignore the market laws. In this sense, the method of free software situates itself inside the movement of history (in the measure in which the development of society's productive forces constitutes the only dimension that, "in the last instance," permits one to detect a direction in it), in the direction of the surpassing of capitalism.

"The center of the free software movement's success, and the greatest achievement of Richard Stallman, is not a piece of computer code. The success of free software, including the overwhelming success of GNU/Linux, results from the ability to harness extraordinary quantities of high-quality effort for projects of immense size and profound complexity. And this ability in turn results from the legal context in which the labor is mobilized. As a visionary designer Richard Stallman created more than Emacs, GDB, or GNU. He created the General Public License."

from E. Moglen, "Anarchism Triumphant", First Monday 4/8, 1999.

New Left Review 15, May-June 2002

Julian Stallabrass on Sam Williams, Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman’s Crusade for Free Software. The iconoclastic hacker who is challenging Microsoft’s dominion, using ‘copyleft’ agreements to lock software source codes into public ownership. Cultural and political implications of treating programs like recipes.

JULIAN STALLABRASS

DIGITAL COMMONS

Stallman argues that while companies address the issue of software control only from the point of view of maximizing profits, the community of hackers has a quite different perspective: ‘What kind of rules make possible a good society that is good for the people in it?’. The idea of free software is not that programmers should make no money from their efforts—indeed, fortunes have been made—but that it is wrong that the commercial software market is set up solely to make as much money as possible for the companies that employ them.

Free software has a number of advantages. It allows communities of users to alter code so that it evolves to become economical and bugless, and adapts to rapidly changing technologies. It allows those with specialist needs to restructure codes to meet their requirements. Given that programs have to run in conjunction with each other, it is important for those who work on them to be able to examine existing code, particularly that of operating systems—indeed, many think that one of the ways in which Microsoft has maintained its dominance has been because its programmers working on, say, Office have privileged access to Windows code. Above all, free software allows access on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. These considerations, together with a revulsion at the greed and cynicism of the software giants, have attracted many people to the project. Effective communities offering advice and information have grown up to support users and programmers.

The free exchange of software has led some commentators to compare the online gift economy with the ceremony of potlatch, in which people bestow extravagant presents, or even sacrifice goods, to raise their prestige. Yet there is a fundamental distinction between the two, since the copying and distribution of software is almost cost-free—at least if one excludes the large initial outlay for a computer and networking facilities. If a programmer gives away the program that they have written, the expenditure involved is the time taken to write it—any number of people can have a copy without the inventor being materially poorer.

An ideological tussle has broken out in this field between idealists, represented by Stallman, who want software to be really free, and the pragmatists, who would rather not frighten the corporations. The term ‘free’, Eric Raymond argues in his book The Cathedral and the Bazaar, is associated with hostility to intellectual property rights—even with communism. Instead, he prefers the ‘open source’ approach, which would replace such sour thoughts with ‘pragmatic tales, sweet to managers’ and investors’ ears, of higher reliability and lower cost and better features’. For Raymond, the system in which open-source software such as Linux is produced approximates to the ideal free-market condition, in which selfish agents maximize their own utility and thereby create a spontaneous, self-correcting order: programmers compete to make the most efficient code, and ‘the social milieu selects ruthlessly for competence’. While programmers may appear to be selflessly offering the gift of their work, their altruism masks the self-interested pursuit of prestige in the hacker community.

In complete contrast, others have extolled the ‘communism’ of such an arrangement. Although free software is not explicitly mentioned, it does seem to be behind the argument of Hardt and Negri’s Empire that the new mode of computer-mediated production makes ‘cooperation completely immanent to the labour activity itself’. People need each other to create value, but these others are no longer necessarily provided by capital and its organizational powers. Rather, it is communities that produce and, as they do so, reproduce and redefine themselves; the outcome is no less than ‘the potential for a kind of spontaneous and elementary communism’. As Richard Barbrook pointed out in his controversial nettime posting, ‘Cyber Communism’, the situation is certainly one that Marx would have found familiar: the forces of production have come into conflict with the existing relations of production. The free-software economy combines elements associated with both communism and the free market, for goods are free, communities of developers altruistically support users, and openness and collaboration are essential to the continued functioning of the system. Money can be made but need not be, and the whole is protected and sustained by a hacked capitalist legal tool—copyright.

The result is a widening digital commons: Stallman’s General Public Licence uses copyright—or left—to lock software into communal ownership. Since all derivative versions must themselves be ‘copylefted’ (even those that carry only a tiny fragment of the original code) the commons grows, and free software spreads like a virus—or, in the comment of a rattled Microsoft executive, like cancer. Elsewhere, a Microsoft vice-president has complained that the introduction of GPLs ‘fundamentally undermines the independent commercial-software sector because it effectively makes it impossible to distribute software on a basis where recipients pay for the product’ rather than just the distribution costs.

Tangentium

TANGENTIUM is an online journal devoted to alternative perspectives on IT, politics, education and society.Tangentium tries to take none of these things for granted. We seek to discuss IT with a critical, political eye. We are not technophobes: far from it. Our intention to use the WWW in the most constructive, Web-literate way we can should serve as evidence (if not proof) of that. But we are aware of some of the great problems which can arise from taking the abovementioned as read.

We also base our discussions, wherever possible, on less orthodox political perspectives. Our favoured viewpoint is a general scepticism towards the political and corporate institutions which currently dominate society.

The Free Software Movement - Anarchism in Action

Asa Winstanley | 22.12.2003 23:45 | Technology

The Limits of Free Software

Asa Winstanley

Of course, the left is not a homogeneous mass; some seem to have a more realistic view. For example, in an article from the New Left Review: "[although] the free exchange of software has led some commentators to compare the online gift economy with the ceremony of potlatch, in which people bestow extravagant presents, or even sacrifice goods, to raise their prestige, it fundamentally differs in that the copying and distribution of software is almost cost-free -- at least if one excludes the large initial outlay for a computer and networking facilities" [4].

Someone call Karl Marx

The means of production is in the hands of the masses and a revolution is under way

The iRevolution is reversing the engines of the Industrial Revolution, and repatriating the means of creative production from the factory to the open hearth of cottage industry. In fact, it could be argued that the home studio is fostering a democratic renaissance in the arts the likes of which we've never seen. Traditionally, the major cultural industries -- movies, TV, radio, music and publishing -- have been controlled by large corporations. If you wanted to be a filmmaker, broadcaster or rock star, you had to rely on the system to sponsor your dreams. Media conglomerates still monopolize pop culture, bankrolling production and distribution. But their grip on the creative process is slipping. With affordable pro technology, artists can create at home and distribute via the Internet. It's a phenomenon that Tyler Cowen, economics professor at Virginia's George Mason University, calls "disintermediation" -- a seven-beat word that means removing the middle ground between producer and consumer.

f open-source data and software invite the democratic overthrow of copyright, sampling is the engine of promiscuity that drives it. And it's changing self-expression the way the sexual revolution changed romance. In cyberspace, everything is up for grabs. We're filtering, filing and recombining data at an unprecedented rate. It's as if we're all busy editing the world -- at least those of us who are hooked up to the IV drip of the Internet. In just a decade or two, we've become a mass culture of file clerks.

In the iWorld, where Google is God, we all behave like tiny search engines, running on the internal combustion of data. Even economist Tyler Cowen admits his daily blogs are a rummage bin of recycled material. "Three-quarters of my posts are me filtering something I've read. I'm parasitic on other people. It's more like being an editor than a writer."

Yet the daily hit of readership is addictive. Cowen says that, like most of his colleagues, he's written scholarly papers that have been read by no more than 20 people. Every day he reaches 10,000 readers with his blog (marginalrevolution.com). He talks about crafting each instalment as if it were a pop song -- "there's always a hook." Just as the iRevolution is democratizing music and film, it's sweeping through the cloistered world of academics, and forcing scholars into the spotlight. The whole notion of "intellectual property," the mortar of academia, is under assault. "My gut feeling," says Cowen, "is that copyright as we know it will collapse."

magine a dance club where everyone's heartbeat is wired for broadcast, and the deejay mixes the amplified tribal pulse into the music. What kind of mass cardiac feedback loop would that create, especially if you factor in designer drugs? Or how about feeling your lover's heartbeat as a vibrating ring tone on your cellphone? Valentine's Day may never be the same. McLuhan talked about media as an extension of our skin. And his metaphor is taking on a more literal truth as technology becomes wearable. The iPod, the camera phone -- and My doki-doki -- are just the beginning. McLuhan's global village is shrinking into the global toytown.

As technology becomes more intimate in scale, the human body will be the last frontier of the iRevolution. The idea of the body as broadcast medium may sound far-fetched -- like something out of David Cronenberg's eXistenZ. But there's no reason to assume the new technology won't be incorporated into fashions of tattooing, piercing and cosmetic surgery. Inevitably there will come a time when wireless communication will be grafted and implanted as interactive media in the flesh. And McLuhan's playful spin on his famous slogan -- the medium is the massage -- will go deeper than he ever could have imagined.

During the Sixties, the New Left created a new form of radical politics: anarcho-communism. Above all, the Situationists and similar groups believed that the tribal gift economy proved that individuals could successfully live together without needing either the state or the market. From May 1968 to the late Nineties, this utopian vision of anarcho-communism has inspired community media and DIY culture activists. Within the universities, the gift economy already was the primary method of socialising labour. From its earliest days, the technical structure and social mores of the Net has ignored intellectual property. Although the system has expanded far beyond the university, the self-interest of Net users perpetuates this hi-tech gift economy. As an everyday activity, users circulate free information as e-mail, on listservs, in newsgroups, within on-line conferences and through Web sites. As shown by the Apache and Linux programs, the hi-tech gift economy is even at the forefront of software development. Contrary to the purist vision of the New Left, anarcho-communism on the Net can only exist in a compromised form. Money-commodity and gift relations are not just in conflict with each other, but also co-exist in symbiosis. The 'New Economy' of cyberspace is an advanced form of social democracy.

Free, anonymous information on the anarchists' Net

London programmer Ian Clarke is putting a little bit of anarchism back in the Net.

Clarke and a growing group of allied programmers are creating a kind of parallel Internet called "Freenet," where censorship is impossible, surfers are anonymous, and content is moved and hosted automatically to points near the people who want it.

The nascent system is a kind of cross between the Net-speeding tools developed by Akamai Technologies and the Napster MP3-swapping software, which is now shaking the music world. Some developers say the mix has created a system that stores and moves content much more efficiently than the ordinary Web.

But at the network's heart lies its creators' conviction that freedom of information should be built directly into the networks, rather than left to the good graces of companies and governments. Freedom from censorship could protect political dissidents and other unpopular speech, but it also means Freenet could provide a safe haven for pornographers and copyright pirates.

And that's fine with its creators.

"Freenet can't afford to make value judgments about the worth of information," said Ian Clarke, the London programmer who began creating the network as a student thesis. "The network judges information based on popularity. If humanity is very interested in pornography, then pornography will be a big part of the Freenet."

Freenet is the latest entry, and perhaps the most ambitious, in a field of new "distributed" network services that are making themselves felt far beyond the technology community.

Programs like Napster, Gnutella, Scour.net's Exchange and others have brought individual computers into the role once played by massive Web hosting services. Want a song, or a video or an image? Instead of searching for it on a Web page, it's now easy to boot up a small program and download it directly from another person's machine.

On a technological level, that's already causing ripples as Internet service providers grapple with the implications of their customers' computers becoming content hosts in their own right. Cox Communications has threatened to drop some San Diego Excite@Home cable-modem subscribers who use the Napster music swapping software, noting that the software clogged its network.

The new technologies are making even more of an impression on the entertainment trade. Napster, Gnutella and their rivals have thrown a panic into the record industry, which sees music listeners trading song files directly, without buying expensive compact discs. Other industries, such as Hollywood filmmakers, also see themselves potentially threatened by the easy file swapping.

Freenet takes these earlier file-swapping programs a step further.

The system is built around the efforts of volunteers, who set up Freenet network "nodes," or connection points, on their own computers to store content. Once a song, document, video or anything else is uploaded into this system, it is distributed around participating computers, automatically stored in nodes near the users who ask for the content, and removed from machines where there is no interest.

The system is designed to be almost entirely anonymous. The actual content on any given host computer changes over time, and will ultimately be encrypted, so no host will know what is on his or her machine. The keywords used to search the network for files are also scrambled, making it extremely difficult for authorities to find out who is hosting what, or who is looking for what particular piece of information.

Critics say this anonymity could protect distribution of genuinely illegal material, such as child pornography or pirated software, music and movies.

While it's impossible to tell how many people are using the system at any given time, about 20,000 people have downloaded an early version of it in the last few weeks, Clarke says.

Anybody can load files into the system and have them hosted by the network's volunteers without paying for bandwidth or a Web site's server space. Clarke uses the example of a band that wants to put its MP3 files online, but can't afford Web space. The band could upload its song onto the system, and as long as people occasionally searched for the song, it would live inside the Freenet.

But others say this is simply transferring the very real costs of bandwidth and storage space to the volunteers in the network. That could make it difficult to keep people participating, as they see their own network connections slowed in the interest of other people's downloads.

"To technologists, that's sexy," said Gene Kam, a Wego.com programmer who is developing Gnutella software. "But to consumers, it's not as good as just logging in and getting free MP3 files."

Others say Freenet, if it is able to get out of its early stages, could be the final nail in the coffin for organizations trying to prevent online piracy. Since Freenet is wholly decentralized, there is no central company to sue for copyright violations. And because each "node" is encrypted, and users anonymous, it will be nearly impossible to track down any individual pirate or pirated work.

"If this takes off, then the (record industry) and (movie industry) are swiftly moving into a world where they have no hope of curbing what they see as a rampant misuse of technology," said Rob Raisch, chief analyst for technology consulting firm Raisch.com.

Industry analysts say the potential for this kind of system, which has added new twists to commercial Internet technologies, has yet to be realized, however.

"I don't think you should think of this as a content distribution system," said Peter Christy, a Jupiter Communications analyst who closely follows the caching industry. "You should think of this as a technology that will allow something else new and exciting that people haven't thought of yet."

A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet

by John Naughton

Published in the UK by Weidenfeld and Nicolson on October 1 1999.

The IBM lawyers were no doubt as baffled by this as they would have been by a potlatch ceremony in some exotic tribe. But to those who understand the Open Source culture it is blindingly obvious what was going on. For this is pre-eminently a high-tech gift economy, with completely different tokens of value from those of the monetary economy in which IBM and Microsoft and Oracle and General Motors exist.

"Gift cultures", writes Eric S. Raymond, the man who understands the Open Source phenomenon better than most, "are adaptations not to scarcity but to abundance. They arise in populations that do not have significant material-scarcity problems with survival goods. We can observe gift cultures in action among aboriginal cultures living in ecozones with mild climates and abundant food. We can also observe them in certain strata of our own society, especially in show business and among the very wealthy".

Abundance makes command relationships difficult to sustain and exchange relationships an almost pointless game. In gift cultures, social status is determined not by what you control but by what you give away. "Thus", Raymond continues, "the Kwakiutl chieftain's potlach party. Thus the multi-millionaire's elaborate and usually public acts of philanthropy. And thus the hacker's long hours of effort to produce high-quality open source".

Viewed in this way, it is quite clear that the society of open-source hackers is in fact a gift culture. Within it, there is no serious shortage of the 'survival necessities' -- disk space, network bandwidth, computing power. Software is freely shared. This abundance creates a situation in which the only available measure of competitive success is reputation among one's peers. This analysis also explains why you do not become a hacker by calling yourself a hacker -- you become one when other hackers call you a hacker. By doing so they are publicly acknowledging that you are somebody who has demonstrated (by contributing gifts) formidable technical ability and an understanding of how the reputation game works. This 'hacker' accolade is mostly based on awareness and acculturation - which is why it can only be delivered by those already well inside the culture. And why it is so highly prized by those who have it.

See:

Tick, Tock, We Live By The Clock

Technocracy In Canada

Not So Green Apple

Capitalism Creates Global Warming

Black History Month; Paul Lafargue

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

agorist, mutalist, anarchist, anarchism, libertarian, left-libertarian, hi tech gift economy, anarchism, libertarianism, mutualism,

IT, gift economy, Apple, Steve Jobs, corporations, workers, Grundrisse,

Marx, Ipod, mobile phones, cell phones, manufacturing, intellectual property, socialism, free market, Proudhon, workers councils, slaves, Ipod, Apple, Steve-Jobs, codes-of-conduct, labour, labor, work, high-tech, manufacturing,

Tags

Anarchism

capitalism

individualism

libertarian communism

socialism

libertarian socialism

mutualism

libertarian