The US government under Donald Trump has already continued building on the imperial legacy of his predecessors. With less than a year in office, his administration has pounded Somalia with airstrikes more than 100 times, attacked Iranian nuclear-enrichment sites, and bombed Syria – where US troops have remained since the Obama years, and where Trump left them during his first term to “keep the oil”. He has also maintained the Biden-era policy of funding Israel’s lethal cleansing and mass starvation in Gaza, and broke a campaign pledge to end the Ukraine war “within 24 hours”, instead continuing to fund it.

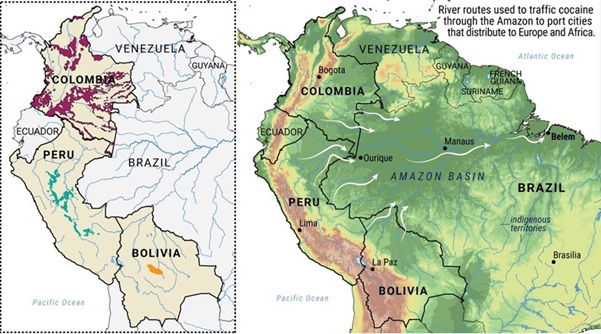

But nowhere is the continuity of American intervention more obvious than in Latin America, where Trump began destroying Venezuelan shipping boats, and – days into the new year—captured Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and brought him back to the US for a trial that will surely be free and fair.

If this seems out of character for the United States, consider the fact that, between 1898 and 1994, Washington intervened in Latin American affairs at least 41 times – about once every twenty-eight months for an entire century. Trump is no aberration; he is simply the latest foreman on a very old job site.

The Global Backlash: How the World Sees US Imperialism

Much like Barack Obama, who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize and then spent eight years bombing seven countries, or George W. Bush, who entered office promising restraint only to preside over nation-building wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Trump has simply continued a decades-long tradition of Republican and Democratic presidents insisting they do not seek war – then waging it anyway once in power.

On the surface, it might seem unprecedented for an American president to bomb a city in a country the United States claims it is not at war with, kill dozens of people on the ground, and kidnap a sitting head of state in the dead of night. But placed in historical context – especially the post-9/11 era – this is not some shocking deviation. It’s a continuation, and the “rules-based international order” Washington loves to lecture about has been shredded by its own architects.

The world has noticed.

A recent international opinion poll shows that in large parts of the globe, the United States is no longer viewed as a stabilizing force, but as one of the greatest threats to their country. According to Pew’s 2025 survey across 25 countries, the US—along with China and Russia – was the most widely viewed as an international threat, with one of them appearing in the top three responses in nearly every nation surveyed.

The Bush Era: Setting the Precedent for Endless War

Starting in 2003 under George W. Bush, the US launched an unjustified invasion of Iraq that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians, with the aftermath still rippling through the region today. Conveniently omitted from Bush’s moral crusade was any mention of America’s crippling economic sanctions against Iraq – which predominantly impacted civilians – or America’s long-standing relationship with Saddam Hussein, which dates back to the 1980s when the US backed his war against Iran with weapons and intelligence, even as he openly used chemical weapons.

Those chemical weapons would become the excuse to invade Iraq, with the US under Bush claiming Saddam not only had hidden stockpiles, but also that he had ties to those behind the attacks of September 11th, 2001. Both claims were false, but it didn’t matter. The US wanted Saddam gone.

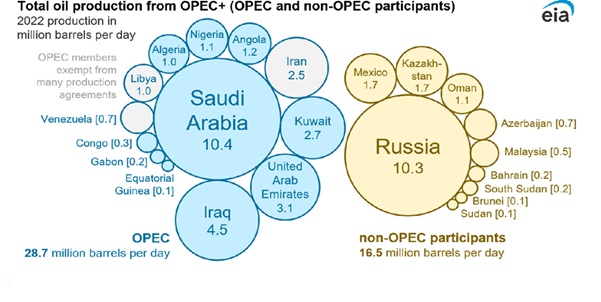

There was also an element of financial geopolitics at play. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Saddam began selling oil in euros under the United Nations’ Oil‑for‑Food Program, challenging the petrodollar system underpinning America’s global financial power. At the same time, Iraq’s vast oil reserves were an attractive prize for energy giants like ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Halliburton, which had lobbied for years to gain access to Iraq’s untapped reserves and stood to benefit immensely from war.

Former members of Bush’s own cabinet – such as Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill – along with US allies such as Britain, later admitted that the administration came into office wanting war with Iraq. And they got their wish.

Early in the invasion, Saddam Hussein’s sons were killed, and the US government made the grotesque decision to release photos of their mangled bodies to the media, broadcasting them like trophies across American nightly news networks. Saddam himself was later pulled from a foxhole, given a cartoonish trial, and executed.

His death marked the end of a long chapter in Iraq’s history, but the next pages would not look much better. The country has been plagued with routine violence, poverty, and outages of water and electricity. Protests have been met with crackdowns. And in certain areas of Iraq, communities have faced devastating rates of horrifying birth defects, along with a sharp increase in leukemia cases, which may be linked to the toxic effects of US munitions. According to research cited in The Guardian, these cancer levels in Fallujah surpassed the peak effects seen in Hiroshima after the US atomic bombing, with leukemia rates rising 2,200% in a shorter timeframe.

America’s largest embassy – the biggest on Earth – now sits in Baghdad, and US troops have yet to leave – remaining through Bush, returning under Obama, and persisting in smaller numbers under Trump and Biden, despite repeated objections from the Iraqi public, which are met with threats by the US. And oil companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron are now deeply embedded in Iraq’s energy sector.

Still, Bush’s so-called “War on Terror” didn’t stop at the Tigris.

In 2002, Washington signaled tacit approval of a coup in Venezuela as US-funded opposition groups and business leaders moved to remove Hugo Chávez after he raised royalties on oil companies like Exxon and moved to further nationalize the country’s oil reserves – the largest in the world.

Additionally, Chávez proposed the creation of ALBA, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, a potential bloc of nations that could operate beyond the realm of US interference, and in mid-2001, he formally requested the departure of US military forces from the Fuerte Tiuna armed forces headquarters in Caracas.

The coup was short-lived.

Chávez was briefly detained by dissident military officers, with business leader Pedro Carmona – who had reportedly met with US officials prior to the attempted overthrow – declaring himself president and immediately dissolving the National Assembly and Supreme Court. Massive demonstrations erupted, key military units refused to recognize the new regime, and Chávez was restored to office within days.

Like Saddam Hussein in Iraq, Chávez continued challenging US financial hegemony by formally creating ALBA in 2004, by establishing Petrocaribe in 2005 – a program offering subsidized oil to Caribbean and Central American nations on non-dollar terms – and by switching some oil sales to euros in 2008, thereby continuing to make Venezuela a prime target for economic sabotage.

The failed coup against Chávez didn’t mark the end of Washington’s efforts against the country, but instead, it set the template. Economic warfare, parallel governments, and bounty-style politics would later replace tanks in the streets.

Next, Washington targeted Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. After ousting him once before in the early 1990s and then restoring him to power in 1994, the US forced him to sign a deal with the World Bank and IMF that privatized state-owned enterprises. Aristide stepped down in 1996 after failing to deliver.

In 2000, he was re-elected. Aristide’s second term was marked by his efforts to double Haiti’s minimum wage, crack down on tax evasion by business elites, and pour money into social programs. He even had the courage to demand France repay Haiti’s “independence debt” – a grotesque sum of 150 million francs that France forced Haiti to pay in 1825 as compensation for the loss of its colony after Haiti’s successful revolution. Demanded under the threat of military intervention, Haiti was forced to borrow the money from French and US banks, plunging the new nation into crippling debt that stunted its development for over a century.

These policies culminated in the February 2004 removal of Aristide, which he termed a “modern-day kidnapping”. Aristide was escorted out of the country by US Marines, removed from office, and ultimately relocated to South Africa.

Former United Nations official Gérard Latortue was named interim prime minister, and his first actions in office included restarting talks with the IMF, World Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank, renewed privatization efforts, and dropping charges against France to repay any owed debts, which France’s former ambassador to Haiti later admitted was one of several reasons they pushed for Aristide’s removal.

By the time Bush left office, the US government had attempted a coup in Venezuela, successfully backed another one in Haiti, and had US troops occupying both Iraq, and also Afghanistan, which a Pentagon memo once termed the “Saudi Arabia of lithium”.

The Obama Era: War in a Hopeful Mask

Barack Obama was supposed to be different. Exhausted by endless war under the Bush years, many Americans easily missed warning signs that his predecessor wouldn’t be much different – such as Obama outpacing a lifelong neoconservative hawk like John McCain on campaign cash from defense companies.

In 2009, Obama’s first year in office, a military coup ousted Honduran president Manuel Zelaya. American officials studiously avoided the word “coup,” yet WikiLeaks cables later showed that the plotters were in steady contact with the US embassy and knew Washington would look the other way.

Zelaya’s offenses were straightforward: he raised the minimum wage, expanded social programs, but perhaps most damning, he took Honduras into ALBA: “The conspiracy began when I started to join what is ALBA, the Latin American nations with Bolivarian Alternative,” Zelaya told Democracy Now in 2011. “So, a dirty war at the psychological level was carried out against me.”

The US didn’t officially pull the trigger – but it helped ensure Zelaya’s removal went smoothly and then backed the regime that reversed his reforms.

According to Zelaya, he was forced out of the country at gunpoint and taken to Soto Cano Air Base (also known as Palmerola), which is a Honduran military facility that also hosts a permanent US military task force. He was then flown to Costa Rica.

The regime that followed his departure withdrew Honduras from ALBA in early 2010, and gutted Zelaya’s social spending initiatives surrounding education and healthcare.

In 2011, the US shifted its toppling efforts across the ocean to Libya, where – joined by European allies – Libya would be systematically destroyed under the banner of preventing a “humanitarian catastrophe”. Not at all ironic considering how these same countries have not acted with nearly the same level of haste to stop Israel’s ongoing massacre in Gaza – infinitely worse by even a marginal comparison.

The offense of Muammar Gaddafi – who had ruled over Libya for decades, often with US and European support – was not humanitarian, but financial.

Two years prior, he had floated the idea of nationalizing the country’s vast oil reserves, coincidentally the largest in Africa, while demanding steep “signing bonuses” from western oil companies seeking to operate in the country. Gaddafi was one of the largest contributors to the African Union, investing over $300 million in the African Development Bank, which funds projects all over the continent. He proposed a gold-backed, African currency, and advocated for “a single African military force, a single currency, and a single passport” allowing Africans to move freely across the continent – what he described as the “United States of Africa”.

In April 2011, leaked cables passed to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton by her advisor Sidney Blumenthal revealed that French intelligence was sweating bullets over Gaddafi’s plan to back a pan‑African currency with Libya’s gold and silver reserves – a move that could have undermined France’s decades-old grip on its former colonies. Most of these countries still use the CFA franc, a currency pegged to the euro and effectively controlled by Paris, giving France enormous influence over West and Central African markets. According to the memo, this threat to French financial dominance, combined with the promise of expanded Libyan influence in Africa, was one of the prime reasons Nicolas Sarkozy decided to drag France into the war.

Matters were not helped by the fact that Gaddafi and his son publicly accused French President Nicolas Sarkozy of accepting Libyan money to fund his 2007 election campaign, an allegation that would later land Sarkozy under criminal investigation.

As such, France became one of the loudest cheerleaders for war alongside the US.

By October of that year, a bloodied and beaten Gaddafi would be dug out of a drainage ditch, captured by western–backed militias and, either dying from his wounds or executed summarily, dumped in an undisclosed desert grave.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton learned of Gaddafi’s death during a live interview and laughed: “We came, we saw, he died.”

Libya was left fractured, impoverished, and crawling with militias, with constant violence and even open slave markets. Western-backed rebels were granted full immunity for any potential war crimes committed during the uprising, Libya’s oil sector reopened on far more agreeable terms, and Gaddafi’s ideas for a gold-backed African currency and united continent were scrapped and forgotten.

A humanitarian success.

Obama also worked to lay the foundation for later administrations by turning the imperial gaze back to Venezuela, first in 2014, by allocating $5 million to “support political competition-building efforts” in Venezuela, and then in 2015, by declaring the country an “extraordinary threat” and imposing targeted economic sanctions.

By the time he left office, the US government under Obama had expanded US drone warfare to an industrial scale, launching airstrikes across the Middle East and Africa. Weddings, funerals, and first responders were all fair game. “Double-tap” strikes ensured that those who came to help the wounded were often killed too. Obama officials reportedly held weekly meetings – nicknamed “Terror Tuesdays” – to decide who would live and who would die. Among those killed was Anwar al-Awlaki, a US citizen living in Yemen who was assassinated in 2011, his only due process arriving in the form of a drone missile. Two weeks later, his 16-year-old son Abdulrahman—never accused of anything—was killed in a separate strike.

The US under Obama also expanded mass surveillance, refused to prosecute brutal CIA torture under the Bush administration, force-fed hunger-striking inmates at Guantanamo Bay, prosecuted more whistleblowers than all previous presidents combined, and – like Bush before him – continued arming Israel as it terrorized occupied Palestinian territory.

When Trump assumed office in January 2017, he would inherit a series of precedents that allowed him to bomb, kill, spy, and torture. Without accountability for the numerous atrocities carried out under Bush and Obama, Trump was free to not only continue their horrors but build his own on top of them.

Trump’s First Term and Biden: No Breaks in the Chain

One of Trump’s first military actions resulted in the death of 8-year-old Nawar al-Awlaki in Yemen – daughter of Anwar al-Awlaki, the US citizen Obama’s drone strike had killed several years earlier.

Eager to hide his bloodshed, Trump loosened rules on civilian-casualty reporting while simultaneously increasing Obama-era drone strikes.

He also established a new precedent for the American empire by openly assassinating a high-ranking Iranian officer – General Qassem Soleimani – nearly igniting a war. UN experts described the strike as illegal under international law. No evidence of an imminent threat was produced, and nobody was ever held accountable.

In Latin America, the US under Trump backed two coups. One failed. One succeeded.

First, in 2019, the Trump administration applauded the removal of Bolivian president Evo Morales, calling it a “strong signal” for “democracy” after the US-funded Organization of American States – created during the Cold War and historically used as a tool for US influence in Latin America – was invited by Bolivia to monitor the election and alleged fraud. As reported by The New York Times, the organization’s “flawed” analysis following the election fueled “a chain of events that changed the South American nation’s history” – a finding supported by independent studies debunking widespread fraud claims.

Not only had US agencies such as the National Endowment for Democracy financed Bolivian civil society and media projects that became prominent voices against Morales during the standoff, but Carlos Mesa – the electoral opponent of Evo Morales – was in direct contact with US embassy officials, discussing strategies to challenge Morales, according to a 2008 diplomatic cable revealed by WikiLeaks.

Morales—who brought Bolivia into ALBA, reduced poverty, nationalized gas fields and telecoms, and kept the country’s vast lithium reserves under state control – fled under military pressure, branding his removal an “act of revenge by the United States which never accepted the loss of control of the Bolivian lithium market in favor of Chinese and German companies.”

“It was a national and international coup d’état,” Morales commented at the time from Buenos Aires. “Industrialized countries don’t want competition.”

Days before the coup, Morales had cancelled a lithium deal with Germany’s ACI Systems Alemania – which makes batteries for companies like Tesla – following local protests in Potosí over low royalties and environmental risks. In response to accusations that the US backed a conspiracy against Morales for Tesla to secure its natural resources, Tesla CEO Elon Musk – who established a foothold in both Trump administrations – tweeted: “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.”

Bolivian Senator Jeanine Áñez declared herself interim president and gained immediate US recognition from the Trump administration. She gutted social programs, broke a decade-long trend and named a new ambassador to the US, withdrew Bolivia from ALBA, granted military forces immunity from criminal prosecution for actions taken to “restore internal order” during protests, all while letting lithium deals signed with countries like China and Germany stall out.

During her short-lived regime, Áñez further signaled her compliance to the United States by joining dozens of US allies and formally recognizing Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela—despite never being elected.

Guaidó—a leader of the opposition party Voluntad Popular – rose to prominence during a period in which US “democracy promotion” programs were active in Venezuela. He contested Nicolás Maduro’s 2018 re-election as illegitimate, declaring himself interim president in January 2019. Just a few weeks prior, he traveled to Washington and met with Organization of American States Secretary General Luis Almagro. On the night before announcing his presidency, US Vice President Mike Pence called Guaidó to confirm US backing. On January 23rd—the same day Guaidó declared himself president – Trump endorsed him.

Denouncing the move as a coup and alleging the US was “desperate to get its hands on our oil”, some of Maduro’s offenses in the eyes of the US included approving “oil for debt” deals with Russia and China, dedicating a portion of the country’s land for state-led mining of gold and other resources, along with strengthening ALBA alliances with non-Western powers such as China and Russia.

Meanwhile, prominent neoconservative John Bolton – who helped write the blueprint for the 2003 US war in Iraq and briefly found a home in Trump’s first-term cabinet – openly admitted on Fox News in January of that year that it would “make a big difference to the United States economically if we could have American oil companies really invest in and produce the oil capabilities in Venezuela.”

By October 2019, the US government was directly funding the “interim government” with “travel, salaries, and secure communications systems.”

For his part, Guaidó took control of Venezuelan assets, vowed to restore diplomatic ties with Israel, and pledged to reopen oil fields to international investors. However, as with the coup attempt against Chávez decades prior, the military didn’t defect, the public didn’t mobilize, and the operation was a humiliating failure for Trump.

In March 2020, Trump issued a $15 million bounty for the capture of Maduro.

When Trump left office in January 2021, his four-year tenure consisted of a failed coup in Venezuela – along with a more successful one in Bolivia – bombing campaigns across Yemen and Somalia, US troops occupying Iraq, support for Israeli atrocities in Palestine, and his administration also kicked off lethal weapon shipments to Ukraine nearly half a decade before war broke out.

Trump also dropped the so-called “Mother of All Bombs” on Afghanistan, the largest non-nuclear weapon in America’s arsenal.

Biden: A Change in Tone, Not Substance

He left in place Donald Trump’s 2019 recognition of opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s “interim president”, treating Nicolás Maduro as illegitimate while also reimposing economic sanctions against the country.

Biden continued targeting ALBA countries like Cuba with economic sanctions, along with Nicaragua’s state-owned gold mining company. Elsewhere around the world, the US under Biden maintained bombing campaigns across Yemen and Somalia, kept US troops in Syria and Iraq, and – even as he oversaw a disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan – the legion of corporations profiting from war still found themselves turning a pretty penny in other theaters.

Over the course of his single term in office, Biden funneled billions upon billions of US-taxpayer dollars into the war in Ukraine—yet halfway through his tenure, the US empire’s depravity escalated even further. Starting in October 2023, the US under Biden began offering an endless supply of financing and weapons to Israel, along with giving diplomatic cover on the international stage to Benjamin Netanyahu and his monstrous regime as it assaulted hospitals, schools, and bakeries under the guise of rooting out Hamas while systematically reshaping the Gaza Strip bomb after bomb, earning Biden the moniker of “Genocide Joe”.

Still, none of this stopped him from making the remarkable claim during a July 2024 address to the nation that he is “the first president this century to report to the American people that the United States is not at war anywhere in the world”.

During his final weeks in office, Biden’s government refused to recognize Maduro’s 2024 inauguration and raised the bounty on his head to $25 million.

The Logical Extension

With decades of US actions around the world unchecked and unchallenged, Trump’s second term is already proving to be one with practically no restraints, revealing a US government that is pure American imperialism with the mask fully removed. Trump’s second term is not a break from the past – it is the logical extension of it.

For decades, the so-called “international community” – a group of nations that has repeatedly proven itself to be either spineless, complicit, or both – has stood by while US administrations under Republicans and Democrats alike have pillaged the world.

Now, as the US is pointing its imperial cannons at Venezuela and Iran, while adding new targets to the list, such as Greenland, the question many have started to ask is:

Where does all of this end, if it ever does, and if there is a line in the sand, where is it?