expert reaction to study looking at generating human-monkey chimeric embryos

A study published in Cell looks at injecting human stem cells into primate embryos to grow human-monkey chimeric embryos.

Dr Alfonso Martinez Arias, Affiliated lecturer, Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, said:

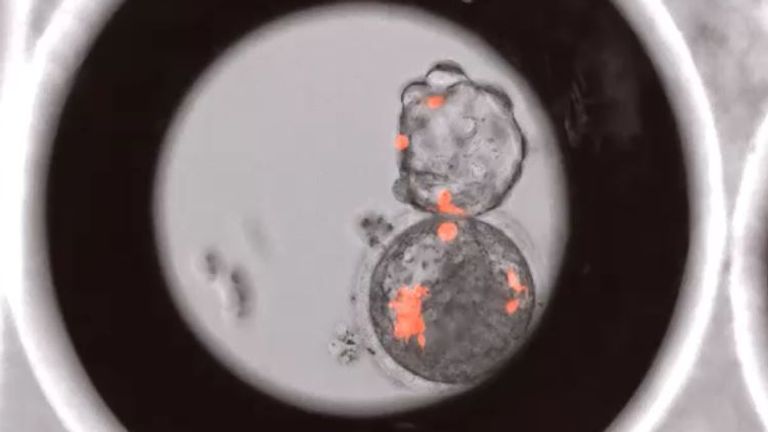

“In my opinion the Cell press release overstates what the results show. For example, it says that ‘After 10 days, 103 of the chimeric embryos were still developing. Survival soon began declining, and by day 19, only three chimeras were still alive’ but in the figures in the manuscript, there is no image of a 19 day old chimera. There is a picture said to be a 19 day embryo but it is impossible to interpret the image. In general the press release is an account of what the ideal experiment would have looked like not what is in the manuscript.

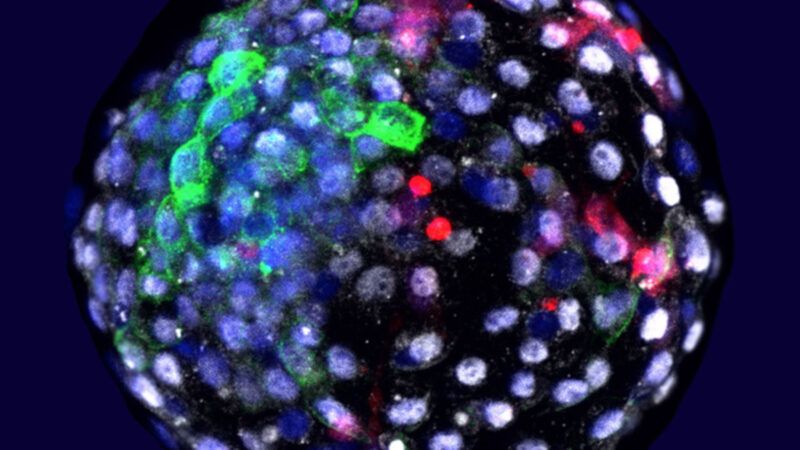

“I think the research is of very low quality. The images of the embryos are extremely poor by current standards and it is impossible to see what they say is there. The manuscript has a total of 9 figures and only 3 of them contain embryos (the gist of the press release), the images are very poor and it is not easy to discern the different cell types. Most importantly there is not a single, clear example of a day 19 chimera which can support their data that 3 embryos survived to this time. The one they show representing a chimera showing different cell types is in Figure 2F and corresponds to a d13 embryo. There is no normal embryo to compare it with but if you do this with published images of human and NH primate embryos, you can see that the one in 2F is very sick. The one d19 they show in Figure 1B is very difficult to accept as an embryo; it is impossible to discern anything. In all cases the specimens appear very sick. In fact the problems are corroborated by the single cell analysis which shows that the human cells are abnormal in the monkey context. I challenge people to find anything in the manuscript that looks like what is drawn in the graphical abstract.

“I do not think that the conclusions are backed up by solid data. The results, in so far as they can be interpreted, show that these chimeras do not work and that all experimental animals are very sick.

“Curiously a related, more rigorous study, was published last year from a group in France on earlier embryos1. It is true that the authors of the French report concluded that these chimeras are not viable beyond day 7. The authors of this new Cell manuscript quote this work but ignore it. Given the lack of evidence for their claim, I would tend to agree with the French group which concluded: ‘that human and non-human primate naive PSCs do not efficiently make chimeras because they are inherently unfit to remain mitotically active during colonization’. In my opinion, the results (as opposed to the statements) of this new work, support this same conclusion.

“This is a complicated area in which, as in the case of the CRISPR babies, society should think and discuss before doing experiments. In my opinion there is extreme overspeculation around this work, particularly given the actual results, and I believe there is a danger that work on this subject of low quality may create a backlash for research on this field.

“I am very surprised that this work has passed peer review and it is of grave concern that work with such technically low quality, could potentially generate big headlines and lead to public concern. Importantly, there are many systems based on human embryonic stem cells to study human development that are ethically acceptable and in the end, we shall use this rather than chimeras of the kind suggested here. Also, chimeras with livestock, as pursued by Hiromitsu Nakauchi, are a more promising route to solve the challenges presented by the authors.

“Statements like the ones in the press release require excellent evidence. In this case this is missing.”

- https://www.cell.com/stem-cell-reports/fulltext/S2213-6711(20)30499-9?_returnURL=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213671120304999%3Fshowall%3D

Prof Martin Johnson, Emeritus Professor of Reproductive Sciences, University of Cambridge, said:

“This study essentially undermines the commonly held understanding that human embryos wouldn’t be studied beyond 14days in vitro. Although not formally doing so given that stem cells, and not embryonic human cells, were injected into monkey blastocysts on day 6.5, nonetheless the experiments amounted to a circumvention of the 14day rule. This sort of experiment would not be necessary if the 14 day rule was changed and thus provides us with a powerful reason to change this rule.”

Sarah Norcross, director of the Progress Educational Trust, said:

“Substantial advances are being made in embryo and stem cell research, and these could bring equally substantial benefits. However, there is a clear need for public discussion and debate about the ethical and regulatory challenges raised.

“Issues raised by this particular research concern the combination of human and nonhuman material (although the embryos in this case were predominantly nonhuman) and how long embryos may be cultured for in the laboratory.

“A related area that deserves further discussion is the creation of synthetic human entities with embryo-like features (SHEEFs) – structures that resemble human embryos, but do not originate from ordinary fertilisation.”

Dr Anna Smajdor, Associate Professor of Practical Philosophy, University of Oslo, said:

“This breakthrough reinforces an increasingly inescapable fact: biological categories are not fixed – they are fluid. This poses significant ethical and legal challenges. Many of the frameworks we rely on to govern our behaviour are based on false assumptions, for example that there is a biological answer to the question ‘what is a human being’?

“The scientists behind this research state that these chimeric embryos offer new opportunities, because ‘we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans’. But whether these embryos are human or not is open to question.”

Prof Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics, and Director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, and Co-Director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, University of Oxford, said:

“The most difficult issue lies in the future. This research opens Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras. These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans. That is one of the long term goals of this research. The key ethical question is: what is the moral status of these novel creatures? Before any experiments are performed on live born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed. What looks like a nonhuman animal may mentally be close to a human. We will need new ways to understand animals, their mental lives and relationships before they used for human benefit.

“Perhaps this will lead us to rethink how animals are treated more generally by humans in science, medicine and agriculture.

“For a fuller discussion of the ethical and legal issues, see:”

https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/6/1/37/5489867

http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2016/07/article-announcement-should-a-human-pig-chimera-be-treated-as-a-person/

‘Chimeric contribution of human extended pluripotent stem cells to monkey embryos ex vivo’ by Tan et al. was published in Cell at 16:00 UK time on Thursday 15th April.

All our previous output on this subject can be seen at this weblink:

www.sciencemediacentre.org/tag/covid-19

Declared interests

Prof Martin Johnson: “I have no conflict of interest.”

Sarah Norcross: “The Progress Educational Trust is a charity which improves choices for people affected by infertility and genetic conditions.”

None others received.

SEE FROM 2019

Scientists grow first ever HUMAN-MONKEY embryo in ‘promising’ step for organ harvesting — RT World News

Human cells grown in monkey embryos reignite ethics debate

Scientists confirm they have produced ‘chimera’ embryos from long-tailed macaques and humans

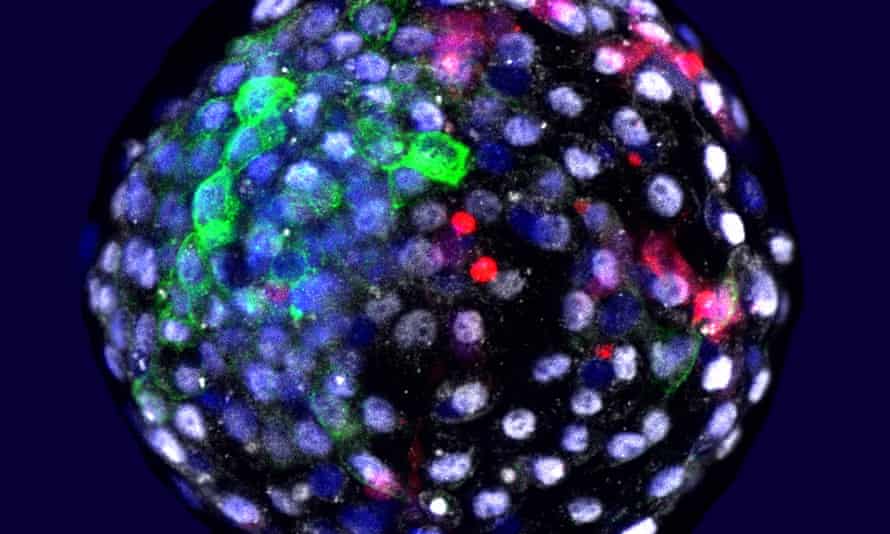

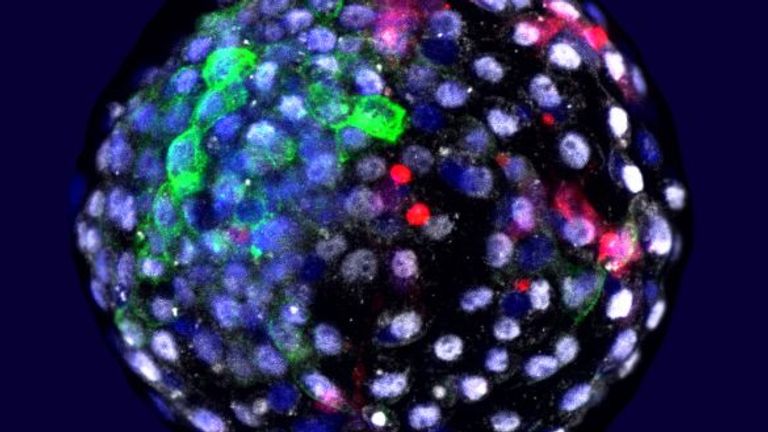

A photo issued by the Salk Institute shows human cells grown in an early stage monkey embryo. Photograph: Weizhi Ji/Kunming University of Science and Technology/PA

Nicola Davis Science correspondent

THE GUARDIAN

Thu 15 Apr 2021

Monkey embryos containing human cells have been produced in a laboratory, a study has confirmed, spurring fresh debate into the ethics of such experiments.

The embryos are known as chimeras, organisms whose cells come from two or more “individuals”, and in this case, different species: a long-tailed macaque and a human.

In recent years researchers have produced pig embryos and sheep embryos that contain human cells – research they say is important as it could one day allow them to grow human organs inside other animals, increasing the number of organs available for transplant.

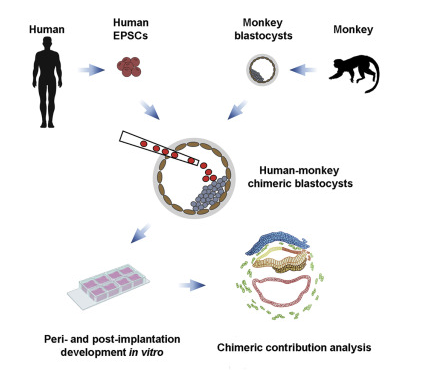

Now scientists have confirmed they have produced macaque embryos that contain human cells, revealing the cells could survive and even multiply.

In addition, the researchers, led by Prof Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte from the Salk Institute in the US, said the results offer new insight into communications pathways between cells of different species: work that could help them with their efforts to make chimeras with species that are less closely related to our own.

“These results may help to better understand early human development and primate evolution and develop effective strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species,” the authors wrote.

The study confirms rumours reported in the Spanish newspaper El País in 2019 that a team of researchers led by Belmonte had produced monkey-human chimeras. The word chimera comes from a beast in Greek mythology that was said to be part lion, part goat and part snake.

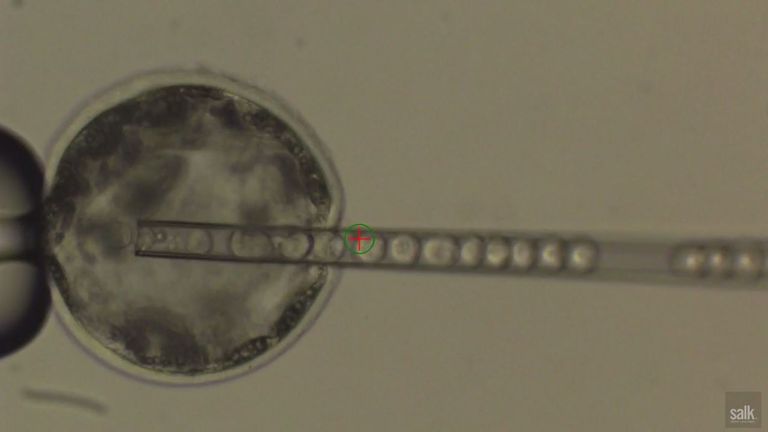

The study, published in the journal Cell, reveals how the scientists took specific human foetal cells called fibroblasts and reprogrammed them to become stem cells. These were then introduced into 132 embryos of long-tailed macaques, six days after fertilisation.

“Twenty-five human cells were injected and on average we observed around 4% of human cells in the monkey epiblast,” said Dr Jun Wu, a co-author of the research now at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

The embryos were allowed to develop in petri dishes and were terminated 19 days after the stem cells were injected. In order to check whether the embryos contained human cells, the team engineered the human stem cells to produce a fluorescent protein.

Among other findings, the results reveal all 132 embryos contained human cells on day seven after fertilisation, although as they developed, the proportion containing human cells fell over time.

“We demonstrated that the human stem cells survived and generated additional cells, as would happen normally as primate embryos develop and form the layers of cells that eventually lead to all of an animal’s organs,” Belmonte said.

The team also reported that they found some differences in cell-cell interactions between human and monkey cells within chimeric embryos, compared with embryos of the monkeys without human cells.

Wu said they hoped the research would help develop “transplantable human tissues and organs in pigs to help overcome the shortages of donor organs worldwide”.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist from the Francis Crick Institute in London, said at the time of the El País report he was not concerned about the ethics of the experiment, noting the team had only produced a ball of cells. But he noted conundrums could arise in the future should the embryos be allowed to develop further.

While not the first attempt at making human-monkey chimeras – another group reported such experiments last year – the new study has reignited such concerns. Prof Julian Savulescu, the director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities at the University of Oxford, said the research had opened a Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras.

“These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans,” he said, adding that a key ethical question is over the moral status of such creatures.

“Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed. What looks like a nonhuman animal may mentally be close to a human,” he said. “We will need new ways to understand animals, their mental lives and relationships before they are used for human benefit.”

Others raised concerns about the quality of the study. Dr Alfonso Martinez Arias, an affiliated lecturer in the department of genetics at the University of Cambridge, said: “I do not think that the conclusions are backed up by solid data. The results, in so far as they can be interpreted, show that these chimeras do not work and that all experimental animals are very sick.

“Importantly, there are many systems based on human embryonic stem cells to study human development that are ethically acceptable and in the end, we shall use this rather than chimeras of the kind suggested here.”

Cell

Cell

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe