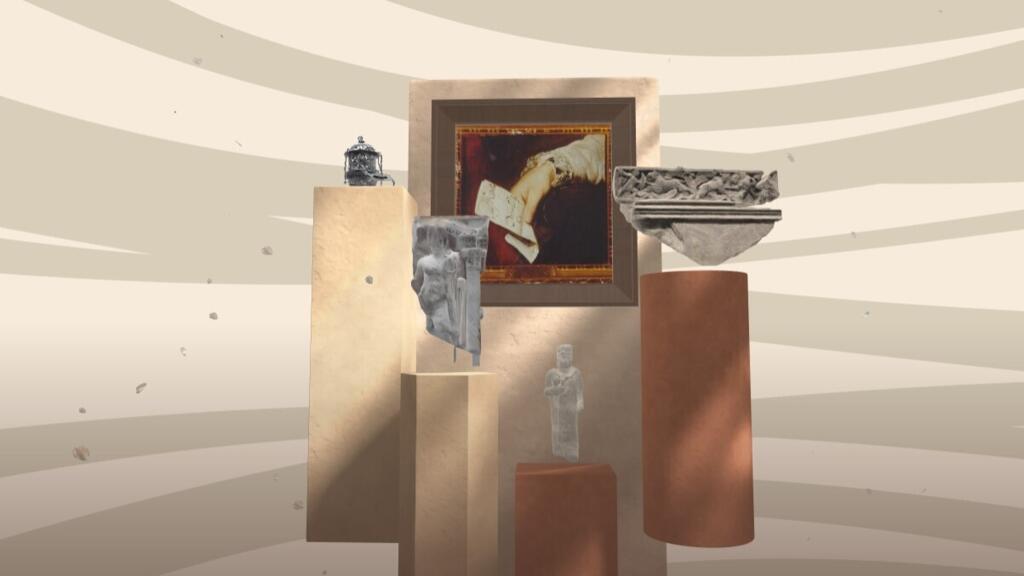

The United Nations' cultural agency UNESCO this week announced the launch of a virtual museum showcasing hundreds of looted artefacts – a bid to educate the public about the consequences of trafficking cultural property.

Issued on: 05/10/2025 - RFI

A Zambian ritual mask, a pendant from the ancient Syrian site of Palmyra and a painting by Swedish artist Anders Zorn are among nearly 250 stolen objects displayed on Unesco's new interactive platform.

But that's just a fraction of the some 57,000 stolen items Interpol estimates are in circulation, in a criminal trade for which the international police organisation's database is the sole reference point.

Unesco director general Audrey Azoulay said she hoped the Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects would draw attention to this vast illegal trade network.

The initiative will inform "as many people as possible" about "a trade that damages memories, breaks the chains of generations and hinders science," Azoulay told French news agency AFP, describing the virtual museum as "unique".

How an RFI investigation helped return an ancient treasure to Benin

'Identity and memory'

The online space, designed by renowned Burkina Faso-born architect Diebedo Francis Kéré, allows visitors to explore the lost objects and trace their origins and purpose through accompanying stories, testimonies and photos.

"Each stolen object takes with it a part of the identity, memory and know-how of its communities of origin," said Sunna Altnoder, head of Unesco's unit for combating illicit trafficking.

The initial collection will grow as more stolen artefacts are 3D-modelled, using artificial intelligence.

Interpol says 11,000 stolen artefacts seized in Europe crackdown

But the goal, Altnoder said, is for it to one day close, as Unesco hopes the pieces will instead move to a Returns and Restitutions section showcasing items recovered or sent back to their countries or communities of origin.

The initiative also aims to bring together sectors involved in tackling the trafficking of cultural property, Altnoder added.

"We need a network – involving the police, the judiciary, the art market, member states, civil society and communities – to defeat another network, which is the criminal network."

(with AFP)