How a Year of Brexit Thumped Britain’s Economy and Businesses

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In the months after Boris Johnson signed his post-Brexit trade deal with the European Union, the coronavirus masked the economic damage of leaving the bloc. As the pandemic drags on, the cost is becoming clearer -- and voters are noticing.

Brexit has been a drag on growth. It brought new red tape on commerce between Britain and its largest and closest market, and removed a large pool of EU labor from the country on which many businesses had come to rely. The combination has exacerbated supply chain shortages, stoked inflation, and hampered trade.

The prime minister hailed the signing of the trade accord almost a year ago as the moment when Britain took back control of its destiny. If it was, voters appear to be increasingly unhappy with the result. According to a November poll by Savanta Comres, a majority of the British population would now vote to re-join the the EU -- including one in ten who voted to leave in the 2016 referendum. In June, only 49% wanted to reverse Brexit.

In recent days, David Frost, Johnson’s key partner in negotiating Brexit, resigned, becoming the third Brexit minister to quit. In his resignation letter, Frost urged Johnson to use Brexit to turn the U.K. into “a lightly regulated, low-tax, entrepreneurial economy” but expressed dismay at the prime minister’s direction of travel, a sign that Brexit is disappointing those who saw it as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to roll back government regulation.

A year on from the signing of the trade deal, here is a look at how Brexit affected British business and the economy, and how the early outcome compares with economists’ and analysts’ predictions.

Trade

Britain’s trade with the EU has declined since the country quit the bloc, with firms hit by new customs paperwork and checks.

As of October, U.K. goods trade with the EU was 15.7% lower than it would have been had Britain stayed in the EU’s single market and customs union, according to modeling by the Centre for European Reform, an independent think-tank. That tallies with a U.K. government analysis of 2018, which predicted a 10% decline in trade.

But the figures may be flattered by the fact the U.K. has delayed implementing many of its post-Brexit border controls until 2022. From January, imports from the EU will need to be immediately accompanied by a customs declaration, and food products will face extra physical inspections from the summer.

Britain has made only limited progress in signing trade deals that go beyond the agreements it enjoyed as a member of the EU. Earlier this month, the U.K. signed its first wholly independent trade deal -- with Australia -- and preliminary terms have been agreed with New Zealand. But the economic boost from both accords is forecast to be limited. A trade deal with the U.S., touted as one of the major prizes of Brexit, appears years away.

Growth

Even before Britain completed its split from the EU at the end of 2020, Brexit had reduced the size of the U.K. economy by about 1.5%, according to estimates from the Office for Budget Responsibility. That was due to a fall in business investment and a transfer of economic activity to the EU in anticipation of higher trade barriers.

Since the U.K.-EU free trade deal came into force, the decline in trade volumes means Brexit is on course to cause a 4% reduction in the size of Britain’s economy over the long-run, according to the OBR. That’s in line with its pre-Brexit forecast.

“A loss of 4-5% of GDP is a big deal,” wrote John Springford, deputy director of the CER, in a research note, agreeing with the OBR’s prediction. “Governments everywhere would leap on a policy that would raise GDP by 5%.”

And of all the regions of the U.K., Northern Ireland -- which remained in the EU’s single market for goods as part of the post-Brexit settlement -- appears to have fared best. The province has largely recovered from the hit of the pandemic, with third-quarter output only 0.3% below the final quarter of 2019, according to data from the Office for National Statistics. The U.K. as a whole is down 2.1% over the same time period.

Labour

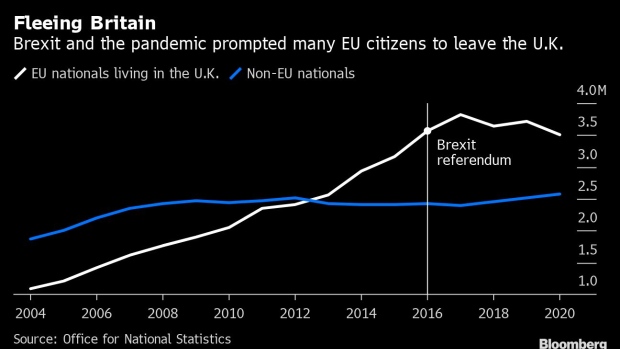

Brexit has exacerbated a crunch in the U.K. labor supply. 200,000 European nationals left Britain in 2020, pushed away by tougher immigration rules and the deepest economic slump in three centuries. That’s helped to trigger staff shortages in sectors such as hospitality and retail, which have historically relied on EU workers, and led to empty shelves.

A smaller pool of EU labor also worsened a fuel crisis in Britain, with a shortfall of tanker drivers contributing to spate of fuel shortages during the summer. Johnson’s government has since eased visa requirements for EU workers, and the driver shortfall has since been reduced as more domestic drivers have been trained.

Finance

Brexit has pushed financial firms to move at least some of their operations, staff, assets or legal entities out of London and into to the bloc -- but the shift has been smaller than predicted, in part because the pandemic has hampered staff relocations.

According to a survey by accounting firm EY published this week, London has lost about 7,400 jobs -- down from an earlier estimate of 7,600. That’s far short of some estimates made before Britain left the bloc. In 2018, Bruegel, a think tank said that London could ultimately lose 10,000 banking jobs and 20,000 roles in the financial services industry.

Britain’s financial firms are still waiting for full access to the EU’s single market, something that relies on the EU granting a so-called equivalence decision. But progress has been glacial as disputes over Northern Ireland have soured EU-U.K. relations.

Read more: JPMorgan’s Paris Traders Are Only Part of the Threat to London

Longer term, the bigger threats to London are likely to come from New York -- which has grown its share of derivatives trading -- and the unseen opportunity cost of new jobs being created in the EU that, but for Brexit, might have been created in the U.K.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

What a mess! The Brexit fiasco

Brexit has not been done. There never was an oven-ready deal. Whatever Johnson thought was ready for the oven is now burnt to a cinder.

It’s time to use ridicule to explain how this UKIP-Tory government has made such a mess of Brexit. Five and a half years since the Brexit referendum, and Liz Truss has just become the sixth minister in charge of getting Brexit done. The public are beginning to understand that Johnson did not have a clue what sort of Brexit he wanted when he was campaigning to leave and is now struggling to come to terms with the failure to deliver.

A succession of incompetent ministers have attempted to reconcile the Leave campaign’s contradictory objectives. We started with David Davis – who went to meetings with Michel Barnier without any briefing papers. He lasted nearly two years as Brexit secretary. Olly Robbins did most of the work, reporting to Theresa May, against a backdrop of hostile briefings from Tory MPs. Dominic Raab picked up the poisoned chalice when Davis and Johnson resigned over May’s Chequers package. He lasted four months, a period distinguished only by his admission that he had not understood how important the port of Dover was.

Stephen Barclay was a steadying influence over the 13 months until the Brexit Department was abolished. Johnson kept him on for a few months after he became Prime Minister but brought in David Frost to do the actual negotiation. Once the UK had left in January 2020 Michael Gove in the Cabinet Office took charge of sorting out the post-Brexit relationship – with Frost as ‘Chief Negotiator’ formally reporting to him, changing status from special adviser to politician on his appointment to the Lords that summer. In March 2021 Frost was made a Minister of State, sidelining Gove and attending the Cabinet. Now he’s resigned because he thinks Johnson is too left-wing, and Liz Truss as foreign secretary takes over the role.

Oh, and the wonderful trade deals that the UK was going to negotiate with the rest of the world have been handled by a newly-created Department of International Trade. Liam Fox, who sincerely believed that the Indians remain so grateful for the benefits of British imperial rule that they would offer us a generous trade agreement, lasted three years as secretary of state, without achieving anything worthwhile. He was confident from long friendships with right-wing US Republicans that Washington would rapidly give Britain a free trade agreement but discovered that US politics is more complicated than he’d imagined.

Johnson replaced him with Liz Truss on becoming prime minister. She’s best known for taking her personal photographer wherever she goes, and for refusing to listen to critical advice. She followed Fox in asserting that geography doesn’t matter when it comes to trade, completed agreements with Australia and New Zealand which most commentators think have given them more advantages than the UK, and has pursued membership of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Her permanent secretary is a New Zealander; there are Australian advisers in No.10. Anne-Marie Trevelyan took over the Department in the summer 2021 reshuffle – comparative stability compared to other Cabinet positions in this chaotic government, with only three secretaries of state in six years.

The Leave campaign ignored well-informed warnings that a hard Brexit would create problems for Northern Ireland – including from a concerned Irish Government. They asserted that they would take back control of Britain’s borders without considering the need for cooperation in border management with those on the other side – a simple truth that I first heard from Finnish officials about relations with the Soviet Union before the cold war had ended. Attacking the French still substitutes for any coherent policy towards our European neighbours – and without a European policy, Britain has no effective foreign policy.

Brexit has not been done. Cross-Channel trade has shrunk sharply, and trade with New Zealand and Australia cannot make up for the loss. Liberal Democrats and others need now to craft an alternative economic and political approach to our European neighbours, on which a policy group is now working. Meanwhile, remind all those who you meet that this government is not only corrupt but also incompetent, on the central issues of international economic strategy and foreign policy.

* Lord Wallace of Saltaire is a Liberal Democrat member of the House of Lords. He has taught at Manchester and Oxford Universities and at the LSE.

Food shortages hitting Britons more than

many in EU, poll finds

Survey suggests UK residents more likely to have faced

shortages than those in France, Germany and Spain

Jon Henley

Wed 22 Dec 2021

Britons are many times more likely to have experienced shortages of food and fuel than people in half a dozen EU member states, according to a poll.

Global supply chain problems prompted by the pandemic have disrupted the international trade network since the summer, with transport backlogs combining with labour shortages to create scarcities of various goods around the world.

The government has argued that the shortages are part of a worldwide pattern and no worse in the UK than elsewhere, although logistics experts and other professionals – particularly in the food sector - have said the problems are amplified in Britain by a shortage of east European workers, including drivers, since Brexit.

The YouGov poll showed residents of the UK were multiple times more likely to have experienced, or to know people who have experienced, shortages of food and fuel than people in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Sweden and Denmark, and somewhat more likely to have experienced them than those in the US.

Asked in early December whether they had personally experienced any scarcity of foodstuffs in recent weeks, 56% of respondents in the UK said yes, while 9% said they had not personally experienced any but knew people who had.

The corresponding figures in the US were 49% and 10%, but in continental Europe, the proportion of people who said they had been personally affected was between three and nine times lower: 18% in Germany, 16% in France, 12% in Sweden, 8% in Denmark, 7% and 6% in Italy.

The proportion saying they knew people who had experienced food shortages ranged from 13% in France to 8% in Denmark and Italy – where 58% of respondents said they were not even aware that supply chain problems had led to food shortages.

The UK was also the only country where substantial numbers of people said they had experienced fuel shortages in recent weeks, since the crisis in September and October. One in three Britons (33%) said they had personally experienced a recent scarcity of fuel, compared with no more than 10% in any other country.

Only 8% of German respondents, 7% of those in France and 5% of those in Italy said they had been personally experienced fuel scarcity, with 37%, 38% and 53% respectively saying they had not even heard of the issue – compared with just 11% of respondents in Britain.

No comments:

Post a Comment