DANIEL RAIMI

Date

JAN. 13, 2022

Image

GTSHUTTERBUG / SHUTTERSTOCK

When assessing the potential benefits and costs of the energy transition, most elected officials, advocates, and media outlets focus on one word: jobs. This focus is understandable and appropriate. Careers shape our sense of identity, create a shared sense of community, and provide for our families. What’s more, everyone can relate to the anxiety, stress, and hardship that come from losing a job—not to mention the excitement and optimism when finding a new one. But another economic issue may be just as important in the energy transition: public finance.

Putting the Pieces Together

In a new working paper from Resources for the Future (RFF), I partner with Emily Grubert of the Georgia Institute of Technology; Jake Higdon of Environmental Defense Fund; Gilbert Metcalf, a university fellow at RFF and professor at Tufts University; RFF Research Analyst Sophie Pesek; and Devyani Singh of Environmental Defense Fund to assess the scale at which fossil fuels contribute to government revenue across the United States—the most comprehensive assessment to date. We also estimate how those revenues might change over the next 30 years under different policy scenarios.

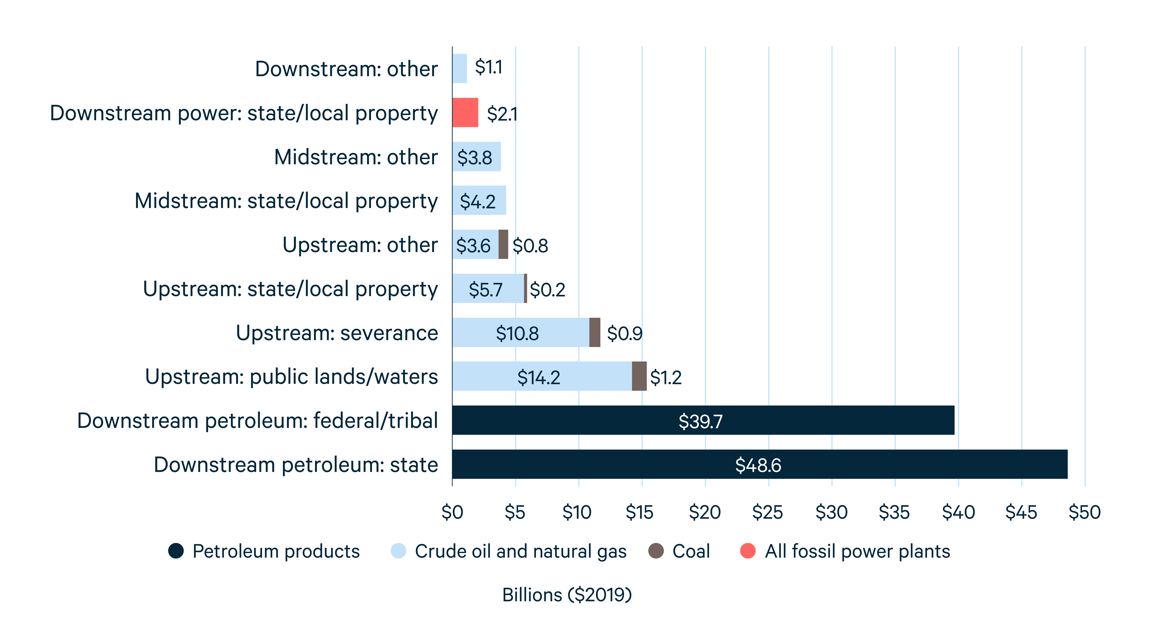

For the past 18 months, we’ve waded through hundreds, if not thousands, of federal, tribal, state, and local government documents, piecing together the myriad ways in which fossil fuels support the public services we all depend on. In total, we estimate that fossil fuels have contributed, on average, about $138 billion per year to governments across the United States between 2015 and 2019. The largest sources of these revenues are petroleum product excise taxes, which have generated $48 billion for states and $40 billion for the federal government annually. Oil and gas production (also known as upstream development) has generated $34 billion annually, led by $14 billion from production on federal, tribal, and state lands and waters; $11 billion from state severance taxes; and $6 billion from local property taxes. Other major sources of these funds include oil and gas pipelines, oil refineries, coal production, and power plants. Figure 1 illustrates our baseline results, grouping each energy type into upstream, midstream (i.e., transportation and refining), and downstream (i.e., consumption) segments.

Figure 1. Annual Average Fossil Fuel Government Revenue by Source, 2015–2019

Source: Raimi et al. (2021). “Other” includes corporate income, personal income, and sales taxes, along with the federal coal excise tax and local property taxes on natural gas distribution. Tribal petroleum product fees are for the Navajo Nation only and average $14 million annually

But how can we compare these public finance numbers with the potential impact on jobs?

Consider the following: based on the most recent data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, total earnings for all employees in oil and gas extraction, coal mining, and support activities for mining (which mostly consists of support for oil and gas extraction) totaled about $31 billion in 2020. We estimate that government revenue from the same set of activities (i.e., extraction of coal, oil, and natural gas) averages more than $37 billion—money that is vital for funding services like schools, public health, and infrastructure. In other words, government revenue may be, in crude financial terms, a more important issue in the energy transition than jobs.

Now, let’s get one thing clear: $138 billion is a big number, but it’s not a reason to avoid or delay taking actions to mitigate climate change. If we use the federal government’s interim estimate for the social cost of carbon ($51 per metric ton), annual damages from energy-sector greenhouse gas emissions in the United States amount to roughly $261 billion per year. And that number is probably too low, as much recent scholarship has pointed to a social cost of carbon that is two or three times larger. When we factor in the additional non-climate damages that fossil fuels impose on human health and the natural environment, the argument to transition quickly to a clean energy economy becomes even stronger.

Checubus / Shutterstock

Nonetheless, that transition to clean energy will create fiscal pressures, particularly in rural regions where fossil fuels are an economic and fiscal linchpin. For example, we estimate that fossil fuels account for more than 10 percent of all state and local government own-source revenue in Wyoming (59 percent), North Dakota (31 percent), Alaska (21 percent), and New Mexico (15 percent). (Own-source revenue is collected directly by local and state governments and excludes transfers from the federal government.) Five more states rely on fossil fuels for more than 5 percent of total state and local own-source revenue: West Virginia (9.4 percent), Montana (7.9 percent), Oklahoma (7.7 percent), Louisiana (7.2 percent), and Texas (7.0 percent). In some other states, such as California, Colorado, and Utah, fossil fuels don’t provide a large share of revenue for the state as a whole, but play an outsized role in local areas such as Kern County, California; Weld County, Colorado; and Uintah County, Utah.

Foreseeing the Fiscal Future of Fossil Fuels

How will these revenues change over the next 30 years? Simple: they’ll most likely decline (Figure 2). Even in a scenario with no new climate policies, we estimate that fossil fuel revenue will be $22 billion lower in 2050, mostly due to declines in gasoline and diesel consumption as the US vehicle fleet becomes more fuel efficient and electrified. Unsurprisingly, more ambitious climate scenarios reduce revenue more dramatically by 2050, with annual revenue falling by $78 billion in a scenario that limits global temperature rise in 2100 to 2°C, and dropping by $111 billion in a 1.5°C scenario.

Figure 2. Baseline and Projected Government Revenues Derived from Fossil Fuels under Three Scenarios

Source: Raimi et al. (2021). Scenarios are based on BP’s 2020 Energy Outlook, which we choose because other scenarios from the International Energy Agency and US Energy Information Administration do not provide sufficient data to estimate future changes under deep decarbonization scenarios in the United States. “BAU” = business as usual. “2°C” and “1.5°C” indicate scenarios that are consistent with limiting temperature rise to international targets of 2°C or 1.5°C above preindustrial levels by 2100.

There’s considerable variation across sectors and fuels under the different scenarios, and this variation has real policy implications. For example, coal revenues decline rapidly under all scenarios and approach zero by 2040 under both the 2°C and 1.5°C scenarios. These projected revenue losses will compound decades of coal-sector decline in Appalachia and exacerbate recent challenges for western coal states, primarily in Wyoming. These communities are on the front line of the energy transition and will need support to diversify their economies and revenue streams.

The implications for the oil and gas sector are more nuanced and vary across scenarios. Oil and gas production remains relatively strong over the next 20 to 30 years under the business-as-usual and 2°C scenarios, but declines more quickly under the 1.5°C scenario. This projected timeline suggests that oil and gas communities will have more time to use natural resource revenues to diversify their economies, build up permanent funds that can support future government revenues, and plan for a clean energy future. Still, the long-term challenge of economic diversification, particularly in rural, resource-dependent regions, suggests that these planning efforts should start now.

Plugging the Holes

Now to the obvious next question: How should we replace declining revenues? That depends—do you want the good news or the bad news first?

First, the good news. We have the policy tools to replace these revenues. As my RFF colleague Marc Hafstead has shown, even a moderate federal carbon price can raise hundreds of billions of dollars per year in revenue. Not all of this revenue would be directed to support government finances, but the money certainly could make a dent. To easily replace declining gasoline and diesel excise taxes, states and the federal government could apply a fee for vehicle miles traveled, which could be calibrated to address multiple externalities like emissions, congestion, accidents, and road damage.

Tweaks to existing energy fiscal policy also could raise revenue. Eliminating subsidies for coal, oil, and natural gas producers and increasing royalty rates for production on public lands could contribute a few billion dollars per year and have the added benefit of phasing out “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,” an important outcome from this year’s COP26 climate pact finalized in Glasgow. A rapidly growing clean energy sector can help raise revenue, too, but comes with some caveats. First, federal policies continue to subsidize clean energy manufacturing and deployment—and some states and localities exempt these technologies from paying local property or other taxes. But scaling back subsidies for clean energy would come with the major downside of slowing the energy transition. In future research, we hope to better assess the mix of fiscal policies that can raise needed revenue for governments without delaying the essential transition to clean energy.

Adwo / Shutterstock

Thinking more broadly across the economy, policy options like a value-added tax, higher marginal income tax rates, and other approaches could easily raise revenues that the federal government could use to support states and localities that are struggling amid the decline of fossil fuels.

All of this brings us to the bad news, which you might have noted already as the elephant in the room. The current political climate of the United States means that prospects for economy-wide carbon pricing, taxes for vehicle miles traveled, fossil fuel subsidy reform, value-added taxes, or higher marginal income tax rates are, on a good day, precarious. Although several of these options have been proposed in Congress recently—most notably in the Build Back Better Act—none have managed to reach the 50-vote threshold in a closely divided Senate.

Could the political prospects for one or more of these reforms change in the years ahead? It’s certainly possible, but when it comes to forecasting the evolution of the median US senator—let alone the 2022 and 2024 elections—I’m out of my depth.

Summing Up

So, where does this leave us? We can distill this whole discussion down to some pretty clear takeaways:

The energy transition will have major consequences for public finances, especially in rural, fossil fuel–producing states and communities.

The reality that governments will lose revenue in a fossil fuel phaseout is not a good reason to delay the energy transition, but it is a challenge that needs to be addressed with policy—most likely including financial transfers from the federal government.

Various policy options could efficiently raise revenues to plug the fiscal holes that will result from a fossil fuel phaseout, but the politics of passing these policies range from tough to toxic.

In the months ahead, RFF’s Equity in the Energy Transition Initiative will build on this work. We’re currently cooking up projects to assess the potential for various tools—including taxes for vehicle miles traveled, clean energy sources, and more—to support public services as the United States and the world moves away from fossil fuels and toward a clean, and more equitable, energy future.

No comments:

Post a Comment