By MATT O'BRIEN and TALI ARBEL

A sign for Microsoft offices, Thursday, May 6, 2021 in New York. Microsoft stunned the gaming industry when it announced, Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022, it would buy game publisher Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion, a deal that would immediately make it a larger video-game company than Nintendo. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

Microsoft stunned the gaming industry when it announced this week it would buy game publisher Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion, a deal that would immediately make it a larger video-game company than Nintendo.

Microsoft, maker of the Xbox gaming system, said acquiring the owner of Candy Crush, Call of Duty, Overwatch and Diablo would be good for gamers and advance its ambitions for the metaverse — a vision for creating immersive virtual worlds for both work and play.

But what does the deal really mean for the millions of people who play video games, either on consoles or their phones? And will it actually happen at a time of increased government scrutiny over giant mergers in the U.S. and elsewhere?

SO, IS IT GOOD FOR GAMERS?

“For the average person who is playing Candy Crush or anything else, there will probably be no changes at all,” said RBC analyst Rishi Jaluria.

But Jaluria and other industry watchers think it could be good news for game development more broadly, especially if Microsoft’s games-for-everybody mission and mountain of cash can rescue Activision from its reputation for abandoning favorite game franchises while focusing on a few choice properties.

“Microsoft wants to increase the variety of intellectual property,” said Forrester analyst Will McKeon-White. “Their target is anyone and everybody who plays video games and they want to bring that to a wider audience.”

He said the “most egregious” example of a popular franchise that Activision, founded in 1979, left by the wayside is StarCraft, last updated in 2015. Others include Guitar Hero, the Tony Hawk skateboarding games and MechWarrior, which McKeon-White said “basically wasn’t touched for two decades.”

On the other hand, the prospect of a console-maker like Microsoft controlling so much game content raised concerns about whether the company could restrict Activision games from competitors.

Microsoft expects to bring as many Activision games as it can to Xbox’s subscription service Game Pass, “with some presumably becoming Microsoft exclusives,” wrote Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter. However, he noted antitrust regulators may not allow Microsoft to keep games off Sony’s competing game console, the PlayStation.

Pachter said that Activision presents a model for Microsoft for how to evolve its classic console franchises. It has adapted Call of Duty into successful mobile and free games, and he expects the company to help Microsoft do the same with its own games, such as Halo.

IS THIS REALLY ABOUT THE METAVERSE?

Microsoft says so. And there are some ways Activision could help the tech giant compete with rivals like Meta, which renamed itself from Facebook last year to signal its new focus on leading its billions of social media users into the metaverse.

Metaverse enthusiasts describe the concept as a new and more immersive version of the internet, but to work it will require a lot of people to actually want to spend more time in virtual worlds. Microsoft’s metaverse ambitions have focused on work tools such as its Teams video chat applications, but online multiplayer games such as Call of Duty and World of Warcraft have huge followings devoted to interacting with each other virtually for fun.

“That’s where Activision really helps,” said RBC’s Jaluria. “Millions of people play Call of Duty online. The community element helps drive adoption.”

Pushing more people into such virtual social networks will not be all fun and games, however, and could amplify existing problems with online harassment, trolling and identity theft, according to Elizabeth Renieris, founding director of the Technology Ethics Lab at the University of Notre Dame.

WILL IT ACTUALLY HAPPEN?

That’s a big unknown. Regulators and rivals could turn up the pressure to block the deal.

Other tech giants such as Meta, Google, Amazon and Apple have all attracted increasing attention from antitrust regulators in the U.S. and Europe. But the Activision deal is so big — potentially the priciest-ever tech acquisition — that Microsoft will also be putting itself into the regulatory spotlight.

“I think it should get a hard look and it probably will get a hard look” by antitrust enforcers, said Diana Moss, president of the American Antitrust Institute. Regulators could ask questions about Microsoft making games exclusive to their own systems and about whether the company would harness user data gained in the acquisition to its advantage in its other businesses.

The Biden administration has been moving to strengthen enforcement against illegal and anticompetitive mergers.

If the deal fails, Microsoft will owe Activision a “break-up fee” of up to $3 billion. That prospect should motivate Microsoft to make concessions to antitrust regulators to get it done, said John Freeman, vice president at CFRA Research.

DOESN’T ACTIVISION HAVE WORKPLACE PROBLEMS?

Activision has attracted unwanted attention from U.S. workforce discrimination regulators, the Securities and Exchange Commission and its own shareholders over allegations of a toxic workplace. California’s civil rights agency also sued the Santa Monica-based company in July, citing a “frat boy” culture that had become a “breeding ground for harassment and discrimination against women.”

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella noted in an investor call Tuesday that “the culture of our organization is my No. 1 priority,” adding that ”it’s critical for Activision Blizzard to drive forward” on commitments made last year to improve its workplace culture. Activision hasn’t made clear if its longtime leader Bobby Kotick, the CEO since 1991, will stick with Microsoft after the deal is closed.

Activision’s legal problems dragged down its stock price and might have made it easier for Microsoft to make a successful takeover bid. But a union representing technology and gaming workers said concerns about working conditions should be considered by U.S. and state officials before any deal is approved.

“Activision Blizzard worker concerns must be addressed in any plan - acquisition or not – on the future direction of the company,” Christopher Shelton, president of the Communications Workers of America, said in a statement.

The Economist

On January 18, Microsoft announced its largest takeover in the company's 46-year history.

Even for Microsoft, which boasts a market capitalisation of around US$2.3 trillion (NZ$3.3t), US$69 billion (NZ$103b) is a lot of money.

On January 18 the firm said it would pay that sum – all of it in cash – for Activision Blizzard, a video-game developer. It is both the biggest acquisition ever made in the video-game industry and the biggest ever made by Microsoft, more than twice the size of the firm’s purchase in 2016 of LinkedIn, a social network, for $26bn.

The move, which caught industry-watchers by surprise and propelled Activision Blizzard’s share price up by 25 per cent, represents a huge bet on the future of entertainment. But not, perhaps, a crazy one.

JAE C. HONG/AP

Microsoft’s acquisition of video-game developer Activision Blizzard is the largest ever made by the firm – twice the size of the firm’s purchase of LinkedIn in 2016. (File photo)

The gaming industry was growing apace before the pandemic. Covid-19 lockdowns bolstered its appeal – to hardened gamers with more time on their hands and bored neophytes alike. Worldwide revenues shot up by 23 per cent in 2020.

NewZoo, an analysis firm, puts them at nearly $180b. Microsoft is already a big player in the business, thanks to its Xbox games console. It has made a string of gaming acquisitions since 2014, when Satya Nadella, its chief executive, took the reins. The Activision Blizzard deal would cement its position. Once completed in 2023, it will make Microsoft the third-largest video-gaming firm by revenue, behind only Tencent, a Chinese giant, and Sony, Microsoft’s perennial rival in consoles.

Activision Blizzard’s share price had slid by around 40 per cent between a peak last February and the deal’s announcement, as the company was embroiled in a sexual-harassment scandal and some of its games underwhelmed. That may have made it look cheap in relative terms, given the benefits it brings to Microsoft. It boasts annual revenues of around $8b and net profit margins of 30 per cent.

Most important, Activision Blizzard offers plenty of content – and in video games, as in the rest of the media industry, content is king, says Piers Harding-Rolls of Ampere Analysis, another research firm. Like the film business, where Star Wars films, even bad ones, are reliable money-spinners, video games rely increasingly on “franchises” – popular settings or brands that can be squeezed for regular new games.

Activision Blizzard boasts, among others, Call of Duty, a best-selling series of military-themed shoot-em-ups, Candy Crush, a popular pattern-matching mobile game, and Warcraft, a light-hearted fantasy setting.

In the short term, the deal gives Microsoft more of a foothold in the smartphone-gaming market, to which it has had little exposure. King, a mobile-focused subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, boasts around 245 million monthly players of its smartphone games, most of whom tap away at Candy Crush.

It is also a strike against Sony. If Microsoft controls the rights to Call of Duty, it can decide whether or not to allow the games to appear on Sony’s rival PlayStation machine. When Microsoft bought ZeniMax Media, another games developer, for $7.5b in 2020, it said it would honour the terms of ZeniMax’s existing publishing agreements with Sony, but that Sony’s access to new games would be considered “on a case-by-case basis”.

Screenshot of video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3. (File photo)

In the longer term, says Harding-Rolls, the deal should help Microsoft achieve its ambition to make gaming cheaper and more accessible (including, if hype is to be believed, in the virtual-reality “metaverse”).

Its “Game Pass” product already offers console and PC gamers access to a rotating library of video games, which usually cost $40-60 each, for $10 a month. Adding Activision Blizzard’s catalogue to the service could boost its appeal. It could also strengthen Microsoft’s two-year-old game-streaming service, which aims to use the firm’s Azure cloud-computing division to do for video games what Netflix did for video.

Microsoft hopes to stream games across the internet to a phone, television or PC, removing the need to own a powerful, dedicated console or PC. That could lower the cost of the hobby and draw in more players, especially in middle-income countries where smartphones are common but consoles are rare. And that, in turn, would make exclusive content even more valuable.

Other firms, both games-industry veterans and arriviste tech titans attracted by the sector’s growth, have streaming ambitions of their own. Sony runs its own service, called “PlayStation Now”. Amazon launched an early version of its own “Luna” service in 2020. “GeForce Now”, a streaming offering from Nvidia, a maker of gaming-focused microchips, launched the same year. But none is as well-placed as Microsoft, which has decades of experience in the games business and boasts the world’s second-largest cloud-computing operation after Amazon.

And the more content Microsoft owns, the more attractive it can make its service compared with its rivals.

Such thinking may provoke more deals by Microsoft’s competitors, eager to snap up franchises of their own while they can. The gaming industry was already seeing plenty of merger activity. Last year saw five deals worth $1b or more.

On January 10 Take-Two Interactive, a game developer and publisher, spent $13b to buy Zynga, a maker of mobile-phone games. Besides Amazon, both Apple and Netflix have dipped their toes into the video-game business in recent years; an acquisition by either one could help boost their presence. Consolidation is the name of the game.

© 2022 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. From The Economist published under licence. The original article can be found on www.economist.com

By —

Geoff Bennett

By —

Karina Cuevas

PBS NEWS

Microsoft announced plans Tuesday to buy Activision Blizzard — a huge leader in game development — in a deal valued at $75 billion. But the acquisition comes with significant issues. There have been numerous allegations of sexual misconduct in the Activision workplace. Geoff Bennett looks at those concerns and others behind the deal.

Judy Woodruff:

Microsoft announced plans today to buy Activision Blizzard, a huge leader in video game development, in a deal valued at $75 billion.

But the acquisition comes with significant issues. There have been numerous allegations of sexual misconduct in the Activision workplace.

Geoff Bennett looks at those concerns and what's behind the deal.

Geoff Bennett:

Judy, thanks to video games subscriptions and the Xbox, Microsoft is already a major player in the gaming market, an industry generating $175 billion a year in revenue.

But acquiring Activision will allow Microsoft to up its own game during a pandemic-fueled gaming boom. Activision is the company behind major hits like "Call of Duty, "World of Warcraft," and "Candy Crush." And the takeover would make Microsoft the world's third largest gaming company.

For more, we're joined by Kirsten Grind of The Wall Street Journal.

Thanks for being with us.

And, if you can, put this number in context for us, this $175 billion, the $75 billion acquisition. What does it mean for the gaming industry generally?

Kirsten Grind, The Wall Street Journal:

It's huge. It's just one of the biggest deals, period, one of the biggest all-cash deals.

And for the gaming industry, it really puts so much under one roof. So you had Xbox and now you have Activision's hits that will be Microsoft. So it gives Microsoft so much more might than it had before.

Geoff Bennett:

And Microsoft, which makes the Xbox consoles, owns studios that produce hits like "Minecraft," it's gotten more aggressive with gaming in the last several years. How does this acquisition play into their long-term tragedy?

Kirsten Grind:

Right.

Well, Activision has so many long term franchises. So, with the addition of Activision there, as you said, they become the largest gaming company by revenue worldwide. So, it absolutely, pending the deal's closure, makes them a very serious player in the space.

Geoff Bennett:

And this deal, as you know and as you have reported, this is coming as Activision faces multiple regulatory investigations into alleged sexual assault and mistreatment of female employees going back years.

And just yesterday, Activision fired several of its own executives following its own investigation, its own review of what transpired. Give us a sense of what is happening within that company. And has Microsoft indicated how it will handle it moving forward?

Kirsten Grind:

That's right.

Well, Activision is really, quite frankly, in trouble with its culture at this point. It's facing three regulatory investigations, the state of California, the EEOC, the Securities and Exchange Commission. We have reported about mishandling of some of the misconduct allegations. Its stock is down about 30 percent from the first of the lawsuits about its culture last summer.

So it was facing pressure from employees, from shareholders. So this is a really — it's kind of a good solution, really, for Activision at this point.

Geoff Bennett:

And based on your reporting, I mean, do you know what happens to Activision's CEO, Bobby Kotick? He's led the company for more than three decades, but there were allegations that he was aware of some of these complaints of misconduct, harassment, even assault, but yet that he neglected to share it with the board.

Kirsten Grind:

That's right.

We reported that in November.And that's actually kind of what led to Microsoft's approach when they were in the middle of all this turmoil after our story came out. And so Bobby actually is not expected to stay with the company after the deal closes. Again, these deals can take a very long time to close, and it's also pending a lot of regulatory approval.

But, yes, he's not expected to stay.

Geoff Bennett:

Can you give us a sense of the nature of what's been alleged?

Kirsten Grind:

Definitely.

So, some of the regulatory agencies have alleged sexual harassment, sexual assault, gender pay disparity, just a broad range of workplace misconduct across the board.

What we wrote about in our November story in The Wall Street Journal was about how Bobby Kotick himself knew about some of these workplace misconduct allegations and didn't tell the board about them.

Geoff Bennett:

Big picture, as we wrap up our conversation here, this acquisition is almost akin to Disney acquiring Marvel back in 2012.

Microsoft will now own a huge piece of the gaming industry, as we have been discussing. What does this mean for gamers generally?

Kirsten Grind:

You know, I think — going back to the culture questions, I think this could be a very good thing for gamers.

I think I heard a lot out there about how it was harder to get behind a company that was facing so many culture issues. And if a company like Microsoft can to help turn that around, I think that would be good for everyone, frankly.

Geoff Bennett:

Kirsten Grind, thanks so much for your reporting and your perspectives on this major deal between Microsoft and Activision.

Kirsten Grind:

Thanks so much for having me.

Game on: Microsoft’s Activision deal ignites M&A talk in rivals

, Bloomberg News

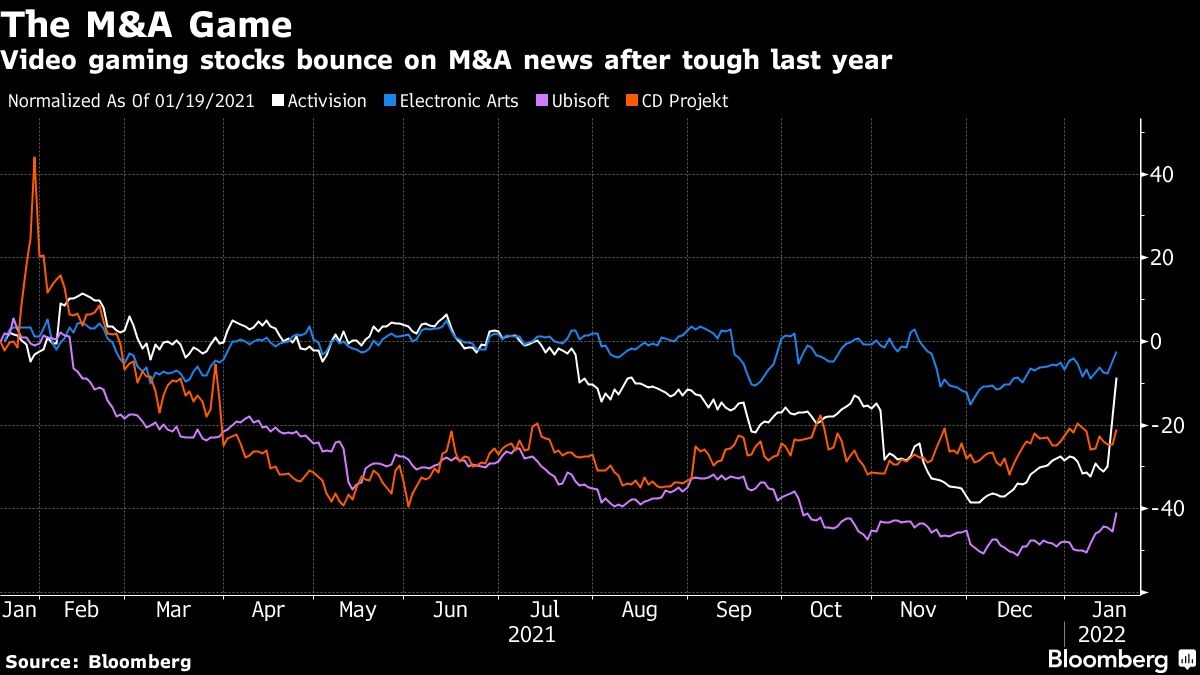

Global gaming stocks rallied after Microsoft Corp.’s landmark US$69 billion takeover bid for Activision Blizzard Inc., a move that could help enliven the sector after a cranky start to 2022.

U.S. rivals Electronic Arts Inc., Take-Two Interactive Software, France’s Ubisoft Entertainment SA and Poland’s CD Projekt SA all rose on Tuesday, with some talked-up as potential acquisition targets. The recent selloff in their shares and rising interest in gaming and the metaverse from large companies such as Meta Platforms Inc. has raised expectations for more deals in the industry.

“If Microsoft can get them over the line without any antitrust issues, the rest are all in play,” said Neil Campling, an analyst at Mirabaud Securities who sees Electronic Arts as “the most obvious takeout target.” Ubisoft is seen as another potential target, but could be hurt by the family holding structure, according to Campling.

Microsoft’s push for Activision follows Take-Two’s recent offer for mobile game maker Zynga Inc. Cowen analyst Doug Creutz writes that the two deals, coming in consecutive weeks, highlights how “these companies carry a lot more strategic value than was being acknowledged by the market.” He speculated that Sony “might have to consider chasing their own blockbuster acquisition, in order to enhance its own exclusive portfolio.” If so, Electronic Arts would be the most logical choice, according to Cowen.

Jordan Klein, a managing director at Mizuho Securities, wrote that there were only a few key names that remained as possible targets, and that Ubisoft, Take-Two, and Electronic Arts could all see valuations expand as potential buyers “could look to make a move.” He noted attractive valuations for Take-Two and especially Electronics Arts, which “has one of the best game title libraries.” He named Netflix Inc., Walt Disney Co., Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc., and Meta Platforms as potential buyers.

Activision shares jumped 26 per cent on Tuesday, while Electronic Arts rose 2.7 per cent and Take-Two rose 1 per cent. The rallies stood out on a day where tech was broadly lower amid ongoing concerns over bond yields. Microsoft fell 2.4 per cent.

Piper Sandler sees Unity Software Inc. as an indirect beneficiary of Microsoft’s move, writing that the deal represents “the beginning of a metaverse arms race.” Shares of Unity fell 4.5 per cent.

No comments:

Post a Comment