Analyses of 17th-century stringed instruments suggest that a young Antonio Stradivari might have apprenticed with a particular craftsman.

The “Hellier” violin, made by Antonio Stradivari in 1679.Credit...Henry Nicholls/Reuters

By Katherine Kornei

June 8, 2022

Sign up for Science Times Get stories that capture the wonders of nature, the cosmos and the human body. Get it sent to your inbox.

History is revealed in tree rings. They have been used to determine the ages of historical buildings as well as when Vikings first arrived in the Americas. Now, tree rings have shed light on a longstanding mystery in the rarefied world of multimillion-dollar musical instruments.

By analyzing the wood of two 17th-century stringed instruments, a team of researchers has uncovered evidence of how Antonio Stradivari might have honed his craft, developing the skills used in the creation of the rare, namesake Stradivarius violins.

Mauro Bernabei, a dendrochronologist at the Italian National Research Council in San Michele all’Adige, and his colleagues published their results last month in the journal Dendrochronologia, and their findings are consistent with the young Stradivari apprenticing with Nicola Amati, a master luthier roughly 40 years his senior. Such a link between the two acclaimed craftsmen has long been hypothesized.

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, Stradivari created stringed instruments renowned for their craftsmanship and superior sound. “Stradivari is generally regarded as the best violin maker who ever lived,” said Kevin Kelly, a violin maker in Boston who has handled dozens of Stradivarius instruments.

Only about 600 of Stradivari’s masterpieces survive today, all prized by collectors and performers alike. A Stradivarius violin currently on the auction block — the first such sale in decades — is predicted to fetch up to $20 million.

By Katherine Kornei

June 8, 2022

Sign up for Science Times Get stories that capture the wonders of nature, the cosmos and the human body. Get it sent to your inbox.

History is revealed in tree rings. They have been used to determine the ages of historical buildings as well as when Vikings first arrived in the Americas. Now, tree rings have shed light on a longstanding mystery in the rarefied world of multimillion-dollar musical instruments.

By analyzing the wood of two 17th-century stringed instruments, a team of researchers has uncovered evidence of how Antonio Stradivari might have honed his craft, developing the skills used in the creation of the rare, namesake Stradivarius violins.

Mauro Bernabei, a dendrochronologist at the Italian National Research Council in San Michele all’Adige, and his colleagues published their results last month in the journal Dendrochronologia, and their findings are consistent with the young Stradivari apprenticing with Nicola Amati, a master luthier roughly 40 years his senior. Such a link between the two acclaimed craftsmen has long been hypothesized.

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, Stradivari created stringed instruments renowned for their craftsmanship and superior sound. “Stradivari is generally regarded as the best violin maker who ever lived,” said Kevin Kelly, a violin maker in Boston who has handled dozens of Stradivarius instruments.

Only about 600 of Stradivari’s masterpieces survive today, all prized by collectors and performers alike. A Stradivarius violin currently on the auction block — the first such sale in decades — is predicted to fetch up to $20 million.

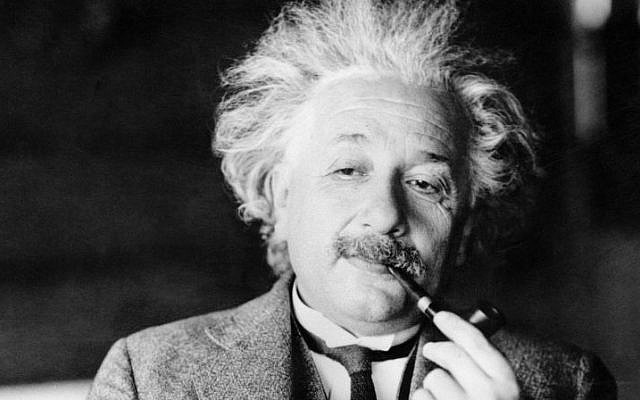

An 18th-century depiction of Antonio Stradivari, the Italian crafter of instruments.

Credit...World History Archive/Alamy

Stradivari likely learned his craft by apprenticing with an older mentor, as was customary at the time. That could have been Amati, who, by the mid-17th century, was well established and also living in Cremona, a city in what is now Italy.

“Some people assume that because Stradivari was Cremonese and he was such a great violin maker, he must have apprenticed with Amati,” said Mr. Kelly, who was not involved in the new study.

But evidence of a link between Stradivari and Amati has remained stubbornly tenuous: One violin made by Stradivari bears a label reading “Antonius Stradiuarius Cremonensis Alumnus Nicolaij Amati, Faciebat Anno 1666.” That wording implies that Stradivari was a pupil of Amati, said Mr. Kelly, but it was the only label like it that has surfaced.

With the goal of shedding light on this musical mystery, Dr. Bernabei and his team visited the Museum of the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella in Naples and analyzed the wood of a small harp made by Stradivari in 1681. Using a digital camera, the researchers precisely measured the widths of 157 tree rings visible on the instrument’s spruce soundboard.

Stradivari likely learned his craft by apprenticing with an older mentor, as was customary at the time. That could have been Amati, who, by the mid-17th century, was well established and also living in Cremona, a city in what is now Italy.

“Some people assume that because Stradivari was Cremonese and he was such a great violin maker, he must have apprenticed with Amati,” said Mr. Kelly, who was not involved in the new study.

But evidence of a link between Stradivari and Amati has remained stubbornly tenuous: One violin made by Stradivari bears a label reading “Antonius Stradiuarius Cremonensis Alumnus Nicolaij Amati, Faciebat Anno 1666.” That wording implies that Stradivari was a pupil of Amati, said Mr. Kelly, but it was the only label like it that has surfaced.

With the goal of shedding light on this musical mystery, Dr. Bernabei and his team visited the Museum of the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella in Naples and analyzed the wood of a small harp made by Stradivari in 1681. Using a digital camera, the researchers precisely measured the widths of 157 tree rings visible on the instrument’s spruce soundboard.

A small harp by Stradivari from 1681.Credit...DeAgostini/Getty Images

The pattern created by plotting the width of tree rings, one after the other, is like a fingerprint. This is because the amount that a trees grows each year depends on the weather, water conditions and a slew of other factors, Dr. Bernabei said. “Plants record very accurately what happens in their surroundings.”

The researchers compared their measurements from the Stradivari harp with other tree ring sequences measured from stringed instruments. Out of more than 600 records, one stood out for being astonishingly similar: a spruce soundboard from a cello made by Nicola Amati in 1679. “All the maximum and minimum values are coincident,” Dr. Bernabei said. “It’s like somebody split a trunk in two different parts.”

The same wood was indeed used to make the Stradivari harp and the Amati cello, Dr. Bernabei and his colleagues suggest. This was consistent with the two craftsmen sharing a workshop, with the elder Amati possibly mentoring the younger Stradivari, the team concluded.

Perhaps that is true, said Mr. Kelly, but it is not the only possibility. Instead, Mr. Amati and Stradivari might simply have purchased wood from the same person, he said. After all, luthiers in 17th-and 18th-century Cremona belonged to a small community, said Mr. Kelly. “They basically all lived on the same street.”

The pattern created by plotting the width of tree rings, one after the other, is like a fingerprint. This is because the amount that a trees grows each year depends on the weather, water conditions and a slew of other factors, Dr. Bernabei said. “Plants record very accurately what happens in their surroundings.”

The researchers compared their measurements from the Stradivari harp with other tree ring sequences measured from stringed instruments. Out of more than 600 records, one stood out for being astonishingly similar: a spruce soundboard from a cello made by Nicola Amati in 1679. “All the maximum and minimum values are coincident,” Dr. Bernabei said. “It’s like somebody split a trunk in two different parts.”

The same wood was indeed used to make the Stradivari harp and the Amati cello, Dr. Bernabei and his colleagues suggest. This was consistent with the two craftsmen sharing a workshop, with the elder Amati possibly mentoring the younger Stradivari, the team concluded.

Perhaps that is true, said Mr. Kelly, but it is not the only possibility. Instead, Mr. Amati and Stradivari might simply have purchased wood from the same person, he said. After all, luthiers in 17th-and 18th-century Cremona belonged to a small community, said Mr. Kelly. “They basically all lived on the same street.”

Stradivarius used by Einstein’s teacher sells for $15.3 million

Instrument belonged to virtuoso Toscha Seidel, who played it in ‘Wizard of Oz’; he and Einstein participated in 1933 concert to support fleeing German Jewish scientists

By AFP

“Of those, many are in museums, many are in foundations and are in situations where they won’t be sold,” Price said.

“There’s a select few which are known as the Golden Period examples, which is approximately between 1710 and 1720,” he said.

“And these, for the most part, are those which are most desired and most highly valued.”

The violin had previously belonged to the Munetsugu collection in Japan. Tarisio did not reveal who the buyer was.

The record for a Stradivarius at auction was set in 2011, when a violin baptized “Lady Blunt,” said to have belonged to Lady Anne Blunt, granddaughter of the poet Lord Byron, was sold for $15.9 in London.

In 2014, another Stradivarius whose auction price was set at a minimum of $45 million did not sell.

Instrument belonged to virtuoso Toscha Seidel, who played it in ‘Wizard of Oz’; he and Einstein participated in 1933 concert to support fleeing German Jewish scientists

By AFP

Today

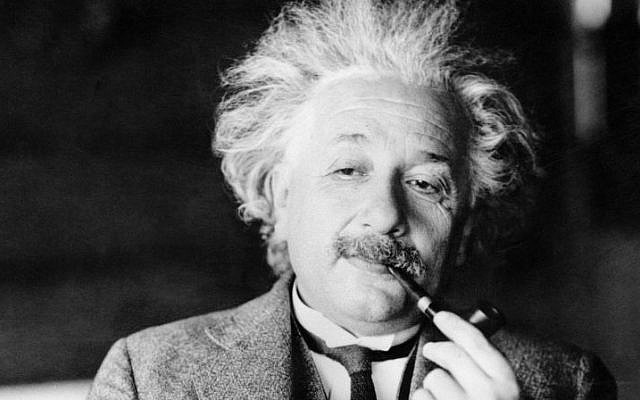

Albert Einstein. (AP Photo)

NEW YORK — A rare Stradivarius violin that belonged to a Russian-American virtuoso and was used in the “Wizard of Oz” soundtrack sold at auction in New York Thursday for $15.3 million, just below the record for such an instrument, according to auction house Tarisio.

The violin, made in 1714 by master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, belonged to virtuoso Toscha Seidel, who not only used it on the score for the 1939 Hollywood classic, but also no doubt while teaching his famous student Albert Einstein.

“This violin has sat side by side with the great mathematician scientist as they played quartets in Albert’s home in Princeton, New Jersey,” said Jason Price, founder of Tarisio, which specializes in stringed instruments.

Seidel, who immigrated to the United States in the 1930s, and Einstein, who fled the Nazi regime in Europe, participated in a New York concert in 1933 in support of fleeing German Jewish scientists.

Of the thousands of instruments made by Stradivari, there are still around 600 known today.

Albert Einstein. (AP Photo)

NEW YORK — A rare Stradivarius violin that belonged to a Russian-American virtuoso and was used in the “Wizard of Oz” soundtrack sold at auction in New York Thursday for $15.3 million, just below the record for such an instrument, according to auction house Tarisio.

The violin, made in 1714 by master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, belonged to virtuoso Toscha Seidel, who not only used it on the score for the 1939 Hollywood classic, but also no doubt while teaching his famous student Albert Einstein.

“This violin has sat side by side with the great mathematician scientist as they played quartets in Albert’s home in Princeton, New Jersey,” said Jason Price, founder of Tarisio, which specializes in stringed instruments.

Seidel, who immigrated to the United States in the 1930s, and Einstein, who fled the Nazi regime in Europe, participated in a New York concert in 1933 in support of fleeing German Jewish scientists.

Of the thousands of instruments made by Stradivari, there are still around 600 known today.

“Of those, many are in museums, many are in foundations and are in situations where they won’t be sold,” Price said.

“There’s a select few which are known as the Golden Period examples, which is approximately between 1710 and 1720,” he said.

“And these, for the most part, are those which are most desired and most highly valued.”

The violin had previously belonged to the Munetsugu collection in Japan. Tarisio did not reveal who the buyer was.

The record for a Stradivarius at auction was set in 2011, when a violin baptized “Lady Blunt,” said to have belonged to Lady Anne Blunt, granddaughter of the poet Lord Byron, was sold for $15.9 in London.

In 2014, another Stradivarius whose auction price was set at a minimum of $45 million did not sell.

No comments:

Post a Comment