Feminist activists placed their own memorial on the plinth where a statue of Christopher Columbus stood for more than a century. Now the government wants to move the anti-monument.

CODY COPELAND / August 13, 2022

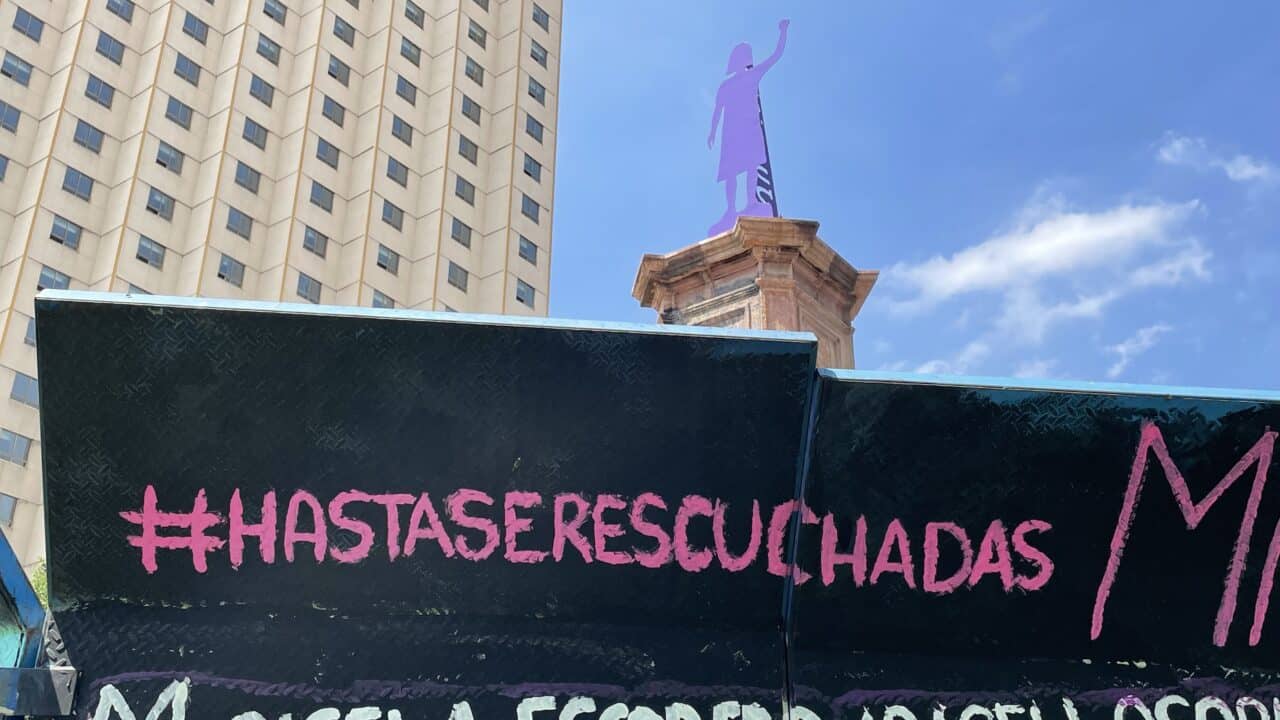

The silhouette of a small girl with her fist raised sits atop the plinth where a statue of Christopher Columbus was removed from Mexico City's Paseo de la Reforma Avenue in October 2020. Feminist activists set up this anti-monument in September 2021. (Cody Copeland/Courthouse News)

MEXICO CITY (CN) — When 21-year-old Jael Monserrat Uribe Palmeros went missing in July 2020, her mother Jacqueline Palmeros quickly realized that she was on her own.

“If I don’t look for my daughter, no one is going to look for her,” said Palmeros, who now organizes a collective of around 30 families who have gone through the same horrifying ordeal.

“The state will give no answer,” she said. “The only ones who are going to help me find her and all the others we’re missing, to find justice for those who are not with us, are our companions who have experienced the same pain.”

To make their struggle visible to Mexican society and to a government that stubbornly refuses to take responsibility for both its actions and inaction, Palmeros and other feminist activists turned to a method of protest that has become more and more popular in recent years: the anti-monument.

The statue of Christopher Columbus on Mexico City’s Paseo de la Reforma Avenue was removed in October 2020, and in September of the following year, the capital government announced plans to replace it with a statue of an indigenous woman’s head inspired by the colossal head statues left by the Olmecs, one of the earliest Mesoamerican peoples.

Members of the feminist coalition Antimonumenta Viva Nos Queremos live stream Jacqueline Palmeros as she tells the story of how they put up the anti-monument at the Roundabout of Women Who Fight during a discussion and book presentation at a Mexico City bookstore on Aug. 12, 2022. (Cody Copeland/Courthouse News)

But Palmeros and other activists rejected the proposal. The artist Pedro Reyes, a mestizo man, had designed what she called “a racialized figure with features of beauty accepted by the Western hegemonic and patriarchal perspective.” It was a “frivolous proposal lacking current contextual, political and social analysis.”

So on Sep. 25, 2021, she and others occupied the median where Columbus had stood since 1877 and placed on the empty plinth a metal statue painted purple of a small girl with her fist raised in defiance, the word “justicia” etched into the support.

They dubbed the median the Roundabout of Women Who Fight and painted the metal barriers the city put up around it with slogans of their movement and the names of victims of gender violence in Mexico.

In other parts of the world the term “anti-monument” is often synonymous with or confused for works of counter-monumentalism, a movement that started in postwar Germany to deal with that country’s legacy of Nazism. Its meaning in Mexico, however, is rather unique.

Whereas counter-monumentalism deals more with artistically subverting the traditional form and meaning of officially sanctioned memorials, anti-monuments in Mexico are guerrilla structures erected by people who organize to carry out that subversion themselves. In a country infamously snarled in unyielding red tape, such radical action is often the only way to break through the bureaucracy.

But Palmeros and other activists rejected the proposal. The artist Pedro Reyes, a mestizo man, had designed what she called “a racialized figure with features of beauty accepted by the Western hegemonic and patriarchal perspective.” It was a “frivolous proposal lacking current contextual, political and social analysis.”

So on Sep. 25, 2021, she and others occupied the median where Columbus had stood since 1877 and placed on the empty plinth a metal statue painted purple of a small girl with her fist raised in defiance, the word “justicia” etched into the support.

They dubbed the median the Roundabout of Women Who Fight and painted the metal barriers the city put up around it with slogans of their movement and the names of victims of gender violence in Mexico.

In other parts of the world the term “anti-monument” is often synonymous with or confused for works of counter-monumentalism, a movement that started in postwar Germany to deal with that country’s legacy of Nazism. Its meaning in Mexico, however, is rather unique.

Whereas counter-monumentalism deals more with artistically subverting the traditional form and meaning of officially sanctioned memorials, anti-monuments in Mexico are guerrilla structures erected by people who organize to carry out that subversion themselves. In a country infamously snarled in unyielding red tape, such radical action is often the only way to break through the bureaucracy.

A hashtag painted on the barriers of the feminist anti-monument reads: "Until we are heard." The panels below list the names of victims of femicide in Mexico.

(Cody Copeland/Courthouse News)

Members of the coalition of feminist organizations known as Antimonumenta Viva Nos Queremos (We Want Us Alive Anti-monument) said the statue is meant to change the function of a monument to bring attention to the present, rather than commemorate the past.

“It’s a site of living memory, a symbol that embraces all the struggles of women, not just one person or group,” said Fernanda, who, like others in the coalition, preferred not to give her last name.

“It’s not about putting up a monument to worship the past, but one to recognize the present fight, all the women who have disappeared,” said fellow activist Érica.

Less than a year after its construction, however, the anti-monument that puts this struggle in the public discourse is now in danger of being silenced. In early August, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum announced that her administration will replace the statue with a replica of a pre-Hispanic sculpture of an indigenous woman and that the Roundabout of Women Who Fight will be moved to a different location in the city.

“It wasn’t just the city government’s idea,” said Sheinbaum in a press conference on Aug. 7. She said the decision was made along with “several groups of indigenous women from various parts of the country… They’re also women who have historically fought for our country. And indigenous women are precisely the ones who have had the least voice, the most discriminated.”

The women of Antimonumenta, however, said that no such dialogue ever took place and that they strictly oppose both the initiative to move the memorial they set up and its replacement with the proposed statue, known as The Young Woman of Amajac.

“Replacing the anti-monument with the Amajac statue is the government’s way of fulfilling a political quota,” said Antimonumenta member Marcela. “They speak of indigenous women, of inclusion, they have a political agenda they must stick to, but there’s no real inclusion.”

Mayor Sheinbaum has not said publicly where her administration plans to move the Roundabout of Women Who Fight. Her office did not respond to Courthouse News’ requests for comment or an interview.

Members of the coalition of feminist organizations known as Antimonumenta Viva Nos Queremos (We Want Us Alive Anti-monument) said the statue is meant to change the function of a monument to bring attention to the present, rather than commemorate the past.

“It’s a site of living memory, a symbol that embraces all the struggles of women, not just one person or group,” said Fernanda, who, like others in the coalition, preferred not to give her last name.

“It’s not about putting up a monument to worship the past, but one to recognize the present fight, all the women who have disappeared,” said fellow activist Érica.

Less than a year after its construction, however, the anti-monument that puts this struggle in the public discourse is now in danger of being silenced. In early August, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum announced that her administration will replace the statue with a replica of a pre-Hispanic sculpture of an indigenous woman and that the Roundabout of Women Who Fight will be moved to a different location in the city.

“It wasn’t just the city government’s idea,” said Sheinbaum in a press conference on Aug. 7. She said the decision was made along with “several groups of indigenous women from various parts of the country… They’re also women who have historically fought for our country. And indigenous women are precisely the ones who have had the least voice, the most discriminated.”

The women of Antimonumenta, however, said that no such dialogue ever took place and that they strictly oppose both the initiative to move the memorial they set up and its replacement with the proposed statue, known as The Young Woman of Amajac.

“Replacing the anti-monument with the Amajac statue is the government’s way of fulfilling a political quota,” said Antimonumenta member Marcela. “They speak of indigenous women, of inclusion, they have a political agenda they must stick to, but there’s no real inclusion.”

Mayor Sheinbaum has not said publicly where her administration plans to move the Roundabout of Women Who Fight. Her office did not respond to Courthouse News’ requests for comment or an interview.

Mexico City residents walk past a wall painted to name the Roundabout of Women Who Fight on Mexico City's Paseo de la Reforma Avenue. (Cody Copeland/Courthouse News)

“To move the anti-monument would be to hide it,” said Marcela. “What the government usually tries to do is place such installations in places with little visibility, and it’s important for us that the defense of memory not end up in the hands of the government, because the government’s memory is selective.”

For Marcela and her fellow activists, the anti-monument marks a tragic miscarriage of justice on the part of the Mexican state.

“The government selects what should be celebrated or recognized, and we call attention to what they want to hide,” she said. “The state wants to hide the fact that 11 to 13 women are murdered each day, that more than 30 people disappear each day. All that they don’t want to be seen is what anti-monuments express.”

Official statistics appear to back up those numbers. At least 10 women are murdered each day in the country, according to Mexico’s National Citizens’ Observatory of Femicide. And the federal government’s National Registry of Disappeared and Missing Persons now includes nearly 104,000 names of forcibly disappeared people.

Relatives of people on that list have set up their own anti-monument down the street from the Roundabout of Women Who Fight, in a traffic circle where a dead palm tree was recently replaced by a Mexican cypress, which itself appears to have already died.

Protecting the feminist anti-monument from the city government’s initiative may prove to be difficult, legally speaking, according to José Roldán Xopa, a research professor of public administration at the Mexico City-based think take CIDE. He said that putting the anti-monument in the space is illegal, despite the legitimacy of any group’s complaint or their constitutional right to protest.

“But this right does not go so far as to appropriation and imposition, or the decision of what to do with that space,” said Roldán. “The government is obligated to receive and consider their petition, but it isn’t necessarily required to grant what they’re asking for.”

“To move the anti-monument would be to hide it,” said Marcela. “What the government usually tries to do is place such installations in places with little visibility, and it’s important for us that the defense of memory not end up in the hands of the government, because the government’s memory is selective.”

For Marcela and her fellow activists, the anti-monument marks a tragic miscarriage of justice on the part of the Mexican state.

“The government selects what should be celebrated or recognized, and we call attention to what they want to hide,” she said. “The state wants to hide the fact that 11 to 13 women are murdered each day, that more than 30 people disappear each day. All that they don’t want to be seen is what anti-monuments express.”

Official statistics appear to back up those numbers. At least 10 women are murdered each day in the country, according to Mexico’s National Citizens’ Observatory of Femicide. And the federal government’s National Registry of Disappeared and Missing Persons now includes nearly 104,000 names of forcibly disappeared people.

Relatives of people on that list have set up their own anti-monument down the street from the Roundabout of Women Who Fight, in a traffic circle where a dead palm tree was recently replaced by a Mexican cypress, which itself appears to have already died.

Protecting the feminist anti-monument from the city government’s initiative may prove to be difficult, legally speaking, according to José Roldán Xopa, a research professor of public administration at the Mexico City-based think take CIDE. He said that putting the anti-monument in the space is illegal, despite the legitimacy of any group’s complaint or their constitutional right to protest.

“But this right does not go so far as to appropriation and imposition, or the decision of what to do with that space,” said Roldán. “The government is obligated to receive and consider their petition, but it isn’t necessarily required to grant what they’re asking for.”

Missing person signs strung up at another intersection of Mexico City's Paseo de la Reforma Avenue constitute an anti-monument claimed by relatives of people who have been forcibly disappeared in Mexico. (Cody Copeland/Courthouse News)

The significance of these anti-monuments reaches beyond those who erect and maintain them, speaking for those who live far from the capital or who are too busy searching for forcibly disappeared loved ones to find time to take part in protests.

“Anti-monuments are very important, because that’s how we raise awareness of the realities people are living,” said Ceci Flores, founder of the Madres Buscadoras de Sonora (Searching Mothers of Sonora) and mother to a disappeared son. While nearly all her time is taken organizing searches for missing persons more than 1,000 miles northwest of the capital, she is grateful for the work of those who set up the anti-monuments in Mexico City.

“There are so many forced disappearances, so many femicides, so many missing children, and the government says it's not happening, that disappearances are decreasing, when in reality they’re increasing,” she said.

“The government trying to take back anti-monument spaces is another way of them trying to silence us,” she said. “It doesn’t want us to keep bringing attention to this. It’s a way to try and stop us from doing so. But they won’t be able to. When you have pain in you, it’s hard not to let it out.”

The significance of these anti-monuments reaches beyond those who erect and maintain them, speaking for those who live far from the capital or who are too busy searching for forcibly disappeared loved ones to find time to take part in protests.

“Anti-monuments are very important, because that’s how we raise awareness of the realities people are living,” said Ceci Flores, founder of the Madres Buscadoras de Sonora (Searching Mothers of Sonora) and mother to a disappeared son. While nearly all her time is taken organizing searches for missing persons more than 1,000 miles northwest of the capital, she is grateful for the work of those who set up the anti-monuments in Mexico City.

“There are so many forced disappearances, so many femicides, so many missing children, and the government says it's not happening, that disappearances are decreasing, when in reality they’re increasing,” she said.

“The government trying to take back anti-monument spaces is another way of them trying to silence us,” she said. “It doesn’t want us to keep bringing attention to this. It’s a way to try and stop us from doing so. But they won’t be able to. When you have pain in you, it’s hard not to let it out.”

No comments:

Post a Comment