Study of ancient adornments suggests nine distinct cultures lived in Europe during the Paleolithic

A team of anthropologists at Université Bordeaux has found evidence of nine distinct cultures living in what is now Europe during the Gravettian period. In their study, reported in the journal Nature Human Behavior, the group analyzed personal adornments worn by people living in the region between 24,000 and 34,000 years ago. Reuven Yeshurun, with the University of Haifa, has published a News & Views piece in the same journal issue, outlining the work done by the team.

Prior research has shown that humans have been adorning themselves for thousands of years. In this new effort, the researchers looked at the types of adornments that were worn by people living in Europe during the Gravettian period—a time during the Paleolithic when a culture known as the Gravettian populated the region.

During this time, people were still hunter–gatherers and dressed themselves in animal skins. They also collected objects to use for adorning themselves, either by attachment to their clothes, their limbs or to their skin. Such objects included animal teeth, bones, ivory, rocks, shells, amber and wood. Some objects were attached or worn as they were, while others were carved or had holes that allowed for attachment via thread.

The researchers looked into the possibility of identifying distinct subcultures among the people living in Europe during the Gravettian period by identifying unique characteristics of their adornments. To that end, they obtained hundreds of such ornamentations and analyzed them to look for patterns.

They found what they describe as consistent differences between groups living in different areas. They found, for example, that people living in what is now Eastern Europe tended to prefer white objects, such as ivory and teeth, whereas those people living on the other side of the Alps tended to gravitate toward more vibrantly colored objects, such as stones and shells. The differences, the team claims, were striking, and strong enough to allow for the identification of nine distinct cultural groups.

More information: Jack Baker et al, Evidence from personal ornaments suggest nine distinct cultural groups between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago in Europe, Nature Human Behaviour (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-023-01803-6

Reuven Yeshurun, Signalling Palaeolithic identity, Nature Human Behaviour (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-023-01805-4

Researchers analyzed more than 100 pieces of prehistoric jewelry and found that the ancient past was more complex than we imagined.

MG

By Mirjam Guesgen

January 30, 2024

Your choice in jewelry can say a lot about you: That you follow a particular religion, graduated with an engineering degree, or you’re just a fan of the latest viral aesthetic.

Now, new research shows that jewelry was just as important for distinguishing different cultures in ancient Europe as it is for signaling your allegiance to a particular group today.

The study, published in Nature Human Behaviour, reveals the existence of nine distinct groups that were lost to time and haven’t conclusively shown up in genetic data. Through the study of ancient artifacts, researchers were able to identify previously-unknown cultures living across Europe between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago, showing the power of these artifacts in writing our complex human histories.

The research focused on people who archeologists had previously thought all belonged to a single group called the Gravettians—Ice Age hunter-gatherers who braved the bitter cold and created some of the most iconic artifacts we know about today, including voluptuous sculptures like the Venus of Willendorf.

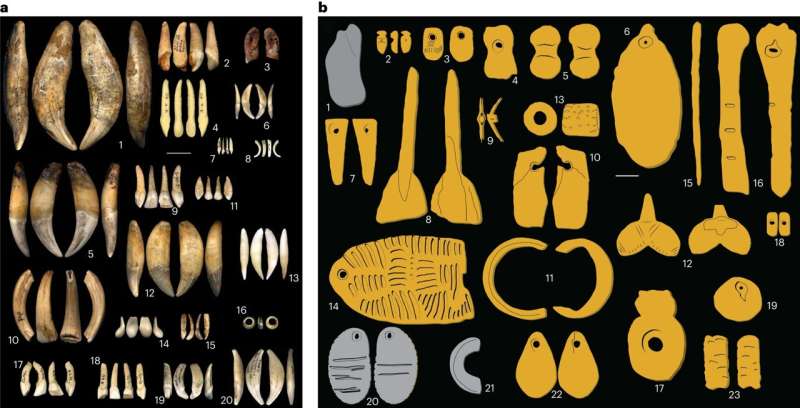

In the study, researchers from France created and analyzed a database of more than 130 personal ornaments from Gravettian burial and housing sites across Europe. The pieces ranged from carved ivory or amber pendants, to beads made from coral or human bone, to barnacle, bear or bison bone adornments.

They first grouped the ornaments based on shared visual characteristics, then looked at where they’d found the objects and put them into subsets. Finally, they ran two different mathematical analyses to confirm that their groupings were valid.

The researchers saw that particular pieces of jewelry clustered together in different locations, representing nine distinct cultural groups, not just one homogenous population. There was a particularly clear split between eastern Europeans—who preferred to wear jewelry made from ivory, stone, or teeth—and western Europeans—who liked shells and teeth, study co-author Jack Baker told Motherboard in an email.

Other recent DNA and archeological evidence had hinted that Gravettians may in fact be a number of different people groups, representing different populations or technical abilities; this latest study puts the proverbial nail in the ancient coffin. “Our results are similar to the DNA evidence but we have shown that sometimes different genetic groups wore the same things and that sometimes the same genetic groups wore the same thing,” said Baker.

“There are some discrepancies between the genetic data and cultural data associated with ornaments,” said Cosimo Posth, an archeologist from Universität Tübingen who wasn’t involved in the study. For example, he points out that the southern Europe Gravettian groups were more similar to the western European groups than to the eastern ones, according to the ornament analysis, whereas the DNA evidence he and his team collected says the opposite. “This is to be expected because obviously different peoples can wear similar ornaments and similar peoples can wear different ornaments, as we see in this case.”

In Posth’s study, he compared DNA evidence with mortuary practices and found good agreement between the two. He says this is a sign that different aspects of culture may have stronger or weaker connections with genetic data. “It seems that certain aspects of a population's culture are more dictated by fashion such as ornaments and others are more related to biological connections such as mortuary practices.”

Some experts say that archeology has come to over-rely on genetic evidence when it comes to painting a picture of our historic past. The authors emphasize the importance of including both personal adornments and biological data when trying to understand paleolithic cultures.

Jewelry doesn’t serve any survival function, unlike other ancient artifacts like spearheads or pottery, so archeologists think it was purely to communicate traits or milestones like reaching a certain age or family ties. “Jewelry was used to transmit social and cultural information, much like today,” Baker, currently a PhD researcher at the Université de Bordeaux, said. “What you wear and how you wear it is a clear and unambiguous signal to others showing which group you belong to. Also, within groups it could show social status—again much like today!”

The messages people alluded to by wearing ornaments changed over time, but some symbols that represented the human body remained relatively unchanged, the study found.

The findings confirmed a theoretical framework known as isolation-by-distance, where people who are closer together geographically will share the same culture by sharing or trading artifacts. The theory therefore predicts that other factors like language, topography, or the environment played a minor role in creating long lasting boundaries between groups.

Of course, what these ornaments were made of comes down to what materials were available wherever people were living. But ultimately, it was culture driving which items they picked from the environment, not the environment dictating what they wore.

No comments:

Post a Comment