Adbar/Wikimedia, CC BY

Billions of federal tax dollars will soon be pouring into Louisiana to fight climate change, yet the projects they’re supporting may actually boost fossil fuels – the very products warming the planet.

At issue are plans to build dozens of federally subsidized projects to capture and bury carbon dioxide from industries.

On the surface, these projects seem beneficial. Keeping carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere prevents the greenhouse gas from fueling climate change. In practice, however, this may lead to a net increase in fossil fuel production and more emissions.

That’s because many of these carbon capture projects will be handling emissions from facilities that rely on oil and natural gas – in fact, many of the projects are tied to major oil and gas companies through subsidiaries. Under new federal rules, the projects can receive generous tax subsidies. The more carbon dioxide the factories produce and capture, the more federal money the projects can receive.

The coup de grâce: Louisiana can authorize as many of these federally subsidized projects as it sees fit. The Environmental Protection Agency recently approved its quest to become only one of three states with regulatory “primacy” over such carbon storage wells.

Fossil fuel industry advocates are eager to get projects approved. “Louisiana has a chance with our geological structures to make a big splash in the pond for CO2 in the world,” Mike Moncla, president of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association, told a legislative task force in December 2023.

Louisiana has taken advantage of disasters to boost the fossil fuel industry before. After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated Louisiana’s marshlands and disrupted oil and gas production in the Gulf of Mexico in 2005, Louisiana authorities pushed to expand drilling in federal waters in the name of hurricane recovery and coastal restoration.

In my book, “Muddy Thinking in the Mississippi River Delta: A Call for Reclamation,” I show how efforts to reduce such environmental destruction end up greenwashing industries that created the problem.

Using disaster to promote fossil fuels

Louisiana has been wrestling with environmental issues and coastal erosion since the early part of the 20th century, sped by a confluence of federal flood control levees on the Lower Mississippi River and oil and gas drilling.

Over the years, the fossil fuel industry drilled thousands of leaky wells and dug over 10,000 miles of pipeline and navigation canals. Coastal erosion accelerated, which also left oil and gas infrastructure exposed.

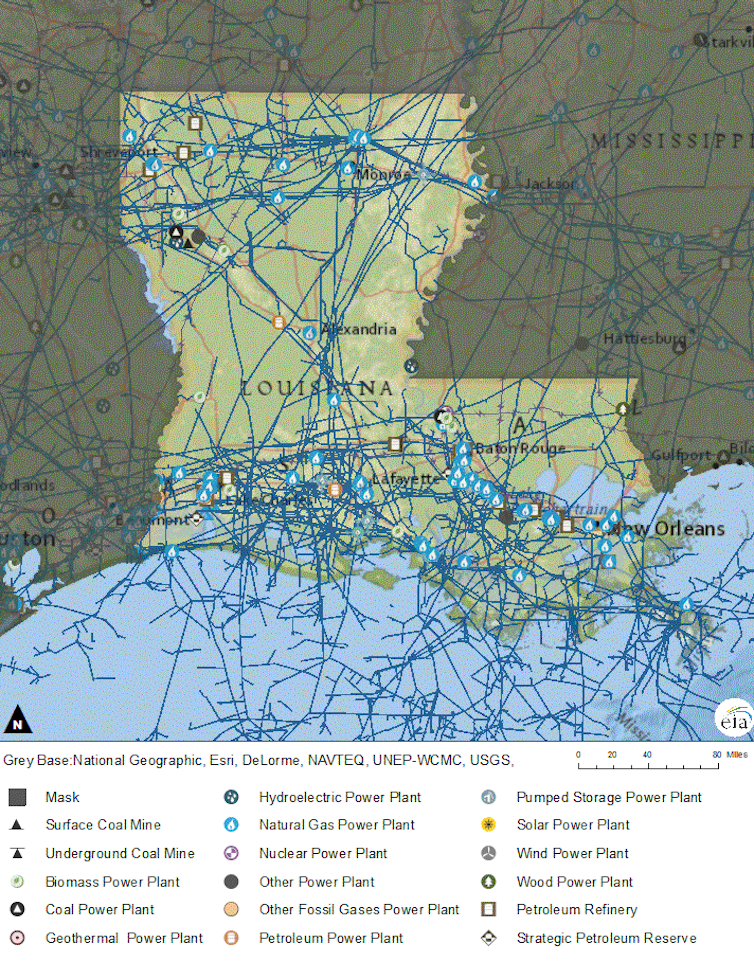

U.S. Energy Information Administration

In the late 1990s, state leaders joined with the oil and gas industry on a public relations campaign to convince Congress to help fund a $14 billion coastal restoration plan. The effort stalled after Congress declined to approve the spending.

Then hurricanes Katrina and Rita hit the state in 2005. Oil and gas production in the region went offline, and U.S. energy prices surged.

Within days of Hurricane Katrina, Republicans in Congress were calling for lifting a 25-year drilling moratorium on the Gulf of Mexico’s Outer Continental Shelf.

Within the year, Congress had voted to lift the moratorium and to share 37.5% of the federal royalties from the wells with Louisiana and the other Gulf states. The money would help fund the state’s coastal restoration plans, which were later bolstered by the huge disaster settlement from BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The arrangement made coastal restoration dependent on future revenue from an industry that continues to damage the coast.

Carbon capture has similarly turned the oil and gas industry into a critical component of mitigating climate change while the industry continues producing products that are heating the planet.

Clearing the way for taxpayer funds

Congress first created a tax credit for carbon sequestration in 2008, but the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act opened the flood gates. It boosted the federal tax credit to $85 per ton of carbon dioxide captured and stored from industrial facilities and $180 per ton for carbon captured from the air and stored. Companies that reuse carbon dioxide for industrial products or enhanced oil recovery will receive $60 per ton.

The tax credits by some estimates could cost the federal treasury well over $100 billion, depending on the program’s popularity, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

At least 24 carbon capture applications are now pending in Louisiana. Many more are in preliminary stages, according to a Louisiana Department of Natural Resources spokesman.

Environmental advocacy groups say the program is riddled with problems, including lacking third-party verification that the carbon is being stored as claimed. An earlier federal investigation by the U.S. Treasury found that 90% of the $1 billion in tax credits awarded to companies for carbon storage between 2010 and 2019 was incorrectly documented.

Globally, there are only about 40 commercial carbon capture, use and storage facilities in operation. They capture 45 million metric tons of carbon annually – just over 1% of global emissions. The vast majority of this captured carbon is used to increase oil production from old wells.

The new gold rush

Carbon capture technology is now being used as a rationale to maintain oil and gas production.

Gregory Upton, executive director of the Louisiana State University Center for Energy Studies, testified on Capitol Hill in September 2023 that the Biden administration’s plan to limit new offshore leases would jeopardize Louisiana’s carbon capture projects. “In my opinion, policies aimed at reducing fossil fuel supply in the U.S. put this decarbonization strategy at risk,” he said.

Indeed, many planned carbon capture projects are tied to natural gas.

For example, a $4.5 billion “blue hydrogen” plant proposed by the Pennsylvania-based company Air Products uses natural gas to produce hydrogen, which also generates carbon dioxide emissions. The company has proposed burying 5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year below Lake Maurepas, and presumably would garner $510 million in tax credits over 12 years.

Communities are worried

Critics argue that using carbon capture as a transition technology will divert billions of dollars in federal resources away from more proven renewable energy development and require building thousands of miles of specialized pipelines.

Capturing and storing emissions also requires energy. Adding carbon capture to a power plant, for example, requires one-sixth to one-third more power production, according to a Congressional Budget Office report. The tax credit rules also don’t account for the emissions released to produce the natural gas or transport and store the carbon dioxide.

When Louisiana petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency for regulatory primacy over these projects, the agency received 45,000 public comments. Residents raised fears that projects would contaminate underground aquifers or that stored carbon dioxide could escape through the state’s thousands of old oil wells.

The company Air Products triggered a public outcry when it began seismic testing with dynamite below Lake Maurepas, which had enjoyed no-dredging, no-drilling protection for decades.

Supporters of the industry, meanwhile, suggested to a state carbon capture task force that resisting even a single project would send a message that Louisiana is not open for business.

But, as I see it, the message seems quite the opposite. With a windfall of federal funding, Louisiana has put out the welcome mat.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment