Trump’s Taxes (Tariffs) on Imports and Sales Taxes on Stocks (FTT)

A Liberia-flagged vehicle cargo ship on the Columbia River, transporting cars from South Korea to the West Coast of the US. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

I have been pushing for financial transactions taxes (FTT) for more than three decades. The logic is straightforward. We have an enormous volume of transactions in the financial sector that serve no productive purpose. Hedge funds and other big actors can buy millions of dollars of stock or other financial assets and then sell them off five minutes or even five seconds later.

While these trades can make some people very rich, they serve no economic purpose. It is important that we have well-working financial markets where businesses can raise capital and people can invest their savings, but these short order trades do not advance these ends. The total volume of trading of stock is now more than $150 trillion a year, more than five times GDP. Trading in bonds would also be in the tens of trillions, while the notional value of trading in options, futures, and other derivative instruments is in the thousands of trillions.

Given the incredible volume of trading, even a modest tax could raise an enormous amount of money, as can be seen with simple arithmetic. If we taxed $150 trillion in stock trades at a 0.1 percent rate (ten cents on one hundred dollars), it would raise $150 billion a year. If we applied scaled taxes to trades of bonds and derivatives we could get to twice this amount, or $300 billion.

However, this would hugely overstate the amount the tax would raise, since there would be a large reduction in trading volume. Most estimates of the impact of higher costs on trading volume find that the reduction in trading volume is roughly proportionate to the increase in trading costs. If the tax doubles trading costs, which this rate roughly would, then we can expect trading volume to be cut in half. That means that this sort of tax could raise roughly $150 billion a year or a bit more than 0.5 percent of GDP.

However, the neat aspect to this tax is the reduction in trading volume caused by the tax is actually a good thing. If we were to tax housing or health care, and people reduced the amount of housing or health care they consumed, that would be a bad story since people value housing and health care. But no one values trading in the same way. If we eliminated $150 billion in trading expenses, this would effectively make the financial sector more efficient, unless there was some reason to believe that it would be less capable of allocating capital or keeping savings secure.

Since even a 50 percent reduction in trading volume would still mean we had very high volumes, and much higher than in prior decades, it is hard to believe that the operations of the financial markets would be seriously impeded. We would just see many fewer people making big fortunes by beating the market by a few hours or seconds. That is bad news for these would be billionaires, but not the sort of thing the rest of us need to worry about. They can look for more productive jobs elsewhere.

So why don’t we have financial transactions taxes? The main reason is that the billionaires who make big bucks on short-term trades make large campaign contributions to politicians to ensure they never get enacted. But special tax treatment of stock sales, as opposed to sales of items like shoes and furniture, in order to protect billionaires’ money, is not a very good political argument.

So instead, we have people jumping up and down yelling about how a FTT would be a tax on the savings of ordinary people. The Wall Street shills tell us that if we imposed a tax of 0.1 percent on stock trades, middle-income people would be nailed on their 401(k)s.

Let’s look at the arithmetic on that. The median 401(k) balance is roughly $140,000. Let’s say 15 percent of this turns over each year or $21,000. If there were a 0.1 percent tax on these trades, that would cost this person $21 a year. Even this is an overstatement, since we would expect that they would reduce their trading volume roughly in proportion to the amount of the tax.

While individuals typically aren’t trading stocks directly in their 401(k)s, we would expect their fund managers to reduce their trading roughly in proportion to the size of the tax. That would mean that their funds would reduce their trading costs by an amount roughly equal to the $21 that the typical 401(k) holder would pay in taxes. The net in this story would be close to zero, with the savings on trading costs offsetting the tax.

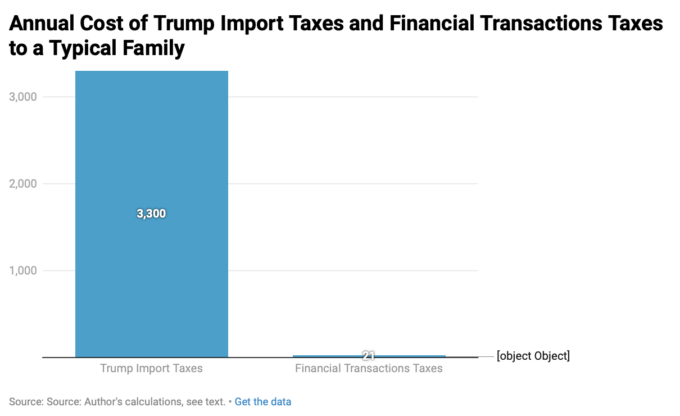

But let’s take the $21 tax bill that is supposedly a big concern for politicians who say they otherwise might be interested in an FTT. President Trump has repeatedly talked about his plans for big taxes on imports or tariffs. While he constantly changes the amount of the taxes he wants to impose and the imports on which he would impose them, the Center for American Progress recently estimated that Trump’s import taxes would cost the typical family $3,300 a year.

There are many reasons for thinking these taxes are bad policy, but it is worth just making the comparison of the size of the tax burden that scares ostensibly progressive politicians away from supporting a financial transaction tax with the burden that Trump’s import taxes would impose, as shown below.

As can be seen, the burden of Trump’s import taxes is more than 150 times as large as the burden from a financial transaction tax on the median 401(k) holder. However, for some reason this burden does not appear to be a major obstacle to putting Trump’s import taxes into effect. Draw your own conclusions.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment