The first fracking-induced earthquake to claim human lives shows why magnitude may underestimate the danger such earthquakes pose

Image credits: Inked Pixels/Shutterstock

Friday, February 21, 2020 - Nala Rogers, Staff Writer

(Inside Science) -- On Feb. 25, 2019, an earthquake shook the village of Gaoshan in China's Sichuan Province, leaving 12 people injured and two dead. New research indicates the earthquake and its two foreshocks were likely triggered by hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking. If this is true, it would mark the first time in history that a fracking-induced earthquake has killed people.

The study shows why magnitude, the most common way of reporting earthquake size, could lead people to underestimate the true threat fracking-induced earthquakes might pose. The Feb. 25 earthquake was only a magnitude 4.9, which would not traditionally be considered very dangerous. But it was able to destroy older and more vulnerable buildings because it was so close to the surface -- only about one kilometer deep according to the new study. That's shallow even by fracking standards, but fracking-induced earthquakes do tend to be much shallower than natural ones.

"The shallower it is, then for the same magnitude of earthquake, the stronger the shaking," said Hongfeng Yang, a seismologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and senior author of the study. The findings are not yet published, but Yang and graduate student Pengcheng Zhou presented them last December at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

How it happened

Fracking involves drilling wells in shale deposits, then pumping in water and other additives at high pressure to break the rock and release trapped oil. In some regions fracking can trigger earthquakes by causing faults in the rock to slip. The slipping happens either because fluids seep into the fault itself, or because the weight or volume of the fluid presses against the fault indirectly, said Thomas Eyre, a seismologist at the University of Calgary in Canada.

Most fracking operations in North America don't cause earthquakes, and the earthquakes that do occur have generally been small. Some media reports have attributed damaging earthquakes in Oklahoma to fracking, but experts believe most of those earthquakes were caused by wastewater that oil and gas developers disposed of by injecting it deep underground. Some of the wastewater included fluids used during the fracking process, but most of it came from ancient underground aquifers, according to Mike Brudzinski, a seismologist at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. The oil beneath Oklahoma is naturally mixed with large volumes of water, and developers must filter out the water before they can sell the oil.

It's a different story in China, however. Several recent studies have shown that the fracking boom that began in about 2014 is triggering destructive earthquakes in formerly tranquil parts of China's Sichuan basin. For example, a magnitude 4.7 earthquake on Jan. 28, 2017, a magnitude 5.7 on Dec. 16, 2018, and a magnitude 5.3 on Jan. 3, 2019 were all caused by fracking, according to published research. The 2018 earthquake injured 17 people and damaged more than 390 houses, nine of which collapsed.

The deadly February 2019 event included a magnitude 4.9 main shock and two smaller foreshocks of magnitudes of 4.7 and 4.3. Using seismic sensors and satellite data, Yang, Zhou and their colleagues found that the foreshocks occurred on a previously unknown fault located within half a kilometer of a fracking well. The foreshocks were between 2.5 and 3 km underground, the same depth where fracking is typically conducted in this region. The main shock struck about eight hours later, on a different, shallower fault a short distance away. The findings suggest that the first two earthquakes and the fluid pumped during fracking may have combined to change the pressures in the rock, causing the second fault to slip.

"It looks to me like some very solid research," wrote Art McGarr, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, in an email, after reviewing a digital copy of the researchers' poster. McGarr has studied induced earthquakes extensively, and was one of the researchers who conducted a recent paper attributing prior Sichuan Basin earthquakes to fracking.

Fracking involves drilling wells in shale deposits, then pumping in water and other additives at high pressure to break the rock and release trapped oil. In some regions fracking can trigger earthquakes by causing faults in the rock to slip. The slipping happens either because fluids seep into the fault itself, or because the weight or volume of the fluid presses against the fault indirectly, said Thomas Eyre, a seismologist at the University of Calgary in Canada.

Most fracking operations in North America don't cause earthquakes, and the earthquakes that do occur have generally been small. Some media reports have attributed damaging earthquakes in Oklahoma to fracking, but experts believe most of those earthquakes were caused by wastewater that oil and gas developers disposed of by injecting it deep underground. Some of the wastewater included fluids used during the fracking process, but most of it came from ancient underground aquifers, according to Mike Brudzinski, a seismologist at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. The oil beneath Oklahoma is naturally mixed with large volumes of water, and developers must filter out the water before they can sell the oil.

Western Canada has experienced a few moderate-sized fracking earthquakes with magnitudes up to about 4.5, but they mostly occurred in remote locations far from major human settlements. And even in western Canada, only about one in 300 fracking operations causes earthquakes large enough for a person to feel, said Eyre.

"In North America at the moment, we haven't had any hydraulic fracturing-induced earthquakes that have actually caused any damage," said Eyre.

It's a different story in China, however. Several recent studies have shown that the fracking boom that began in about 2014 is triggering destructive earthquakes in formerly tranquil parts of China's Sichuan basin. For example, a magnitude 4.7 earthquake on Jan. 28, 2017, a magnitude 5.7 on Dec. 16, 2018, and a magnitude 5.3 on Jan. 3, 2019 were all caused by fracking, according to published research. The 2018 earthquake injured 17 people and damaged more than 390 houses, nine of which collapsed.

The deadly February 2019 event included a magnitude 4.9 main shock and two smaller foreshocks of magnitudes of 4.7 and 4.3. Using seismic sensors and satellite data, Yang, Zhou and their colleagues found that the foreshocks occurred on a previously unknown fault located within half a kilometer of a fracking well. The foreshocks were between 2.5 and 3 km underground, the same depth where fracking is typically conducted in this region. The main shock struck about eight hours later, on a different, shallower fault a short distance away. The findings suggest that the first two earthquakes and the fluid pumped during fracking may have combined to change the pressures in the rock, causing the second fault to slip.

"It looks to me like some very solid research," wrote Art McGarr, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, in an email, after reviewing a digital copy of the researchers' poster. McGarr has studied induced earthquakes extensively, and was one of the researchers who conducted a recent paper attributing prior Sichuan Basin earthquakes to fracking.

Shallow depth increases danger

The magnitude 4.9 earthquake last February damaged buildings in Gaoshan in part because the buildings were old and not designed for earthquake safety, said Yang. The location was densely populated and didn't have a history of dangerous earthquakes, so it was highly vulnerable.

But even so, the earthquake would have been less damaging had it occurred 5 to 20 km underground, as most natural earthquakes do, according to Brudzinski. Instead, it occurred about a kilometer underground, with hardly any rock to absorb the shock before it reached the surface. Most fracking-related earthquakes are less than 5 km deep.

"We always pin everything on the magnitude, so that can be kind of misleading," said Pradeep Talwani, a geophysicist at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. According to Talwani, people in Gaoshan probably felt more shaking from the shallow magnitude 4.9 quake than someone in Seattle would feel from a natural magnitude 6.5 earthquake that struck deep beneath their feet.

Magnitude is a measure of the total amount of energy released during an earthquake, and researchers estimate it by calculating the surface area of a fault and the distance it has slipped, said Brudzinski. What actually matters to a person on the surface is how much the ground they're standing on shakes and how that affects structures around them -- a concept known as intensity, which researchers estimate using a variety of scales. Intensity depends in part on the earthquake's magnitude, but also on its depth, lateral distance away, and the types of rock and soil in the area.

"Right now, most regulations are still based on the magnitude. But there's a recognition now, a growing recognition, that the true risk is related to what kind of structures are there, what kind of soil they're built on, how shallow those earthquakes might be," said Brudzinski.

Deadly earthquakes continue

After the Feb. 25 earthquake that killed two people in Gaoshan, the local government halted fracking, said Yang. But in surrounding parts of the Sichuan Basin, fracking continues. According to online reports by the China Earthquake Administration, several more damaging earthquakes struck the region later in 2019:

• A magnitude 6.0 on June 17 in Changning County that killed at least 13 people and injured 220

• A magnitude 5.4 on Sept. 8 in Weiyuan County that killed one person and injured 63

• A magnitude 5.2 on Dec. 18 in Zizhong County that injured at least nine

Yang, Zhou and their colleagues have not yet analyzed these earthquakes, and according to Zhou, it is not yet clear whether they were fracking-induced. The Chinese government has denied that the June 17 earthquake that killed 13 people was caused by fracking, according to reporting by Reuters. A recent study suggested it may have been triggered by a combination of salt mining and a previous fracking-induced quake.

Despite multiple attempts over several weeks, Inside Science has been unable to obtain comment from anyone affiliated with the China Earthquake Administration regarding either the earthquakes in 2017, 2018 and early 2019 or the more recent ones that haven't yet been analyzed in detailed studies. The administration has reported greater depths for Sichuan Province earthquakes than would be expected if they were caused by fracking. However, those numbers don't match up with the shallow depth estimates from detailed studies, including Yang and Zhou's research and several published studies that included China Earthquake Administration researchers as authors.

Yang said he wasn't surprised that the depth estimates differ. He explained that the China Earthquake Administration's online reports use estimates that are generated automatically using a network of stationary seismic sensors and a general-purpose model. He claimed that his own study and other studies that have pinpointed shallower depths are much more accurate. That's because they use additional data sources and models that are customized for specific locations, he said.

It's unlikely that any of the earthquakes highlighted in this story occurred naturally, according to McGarr. The northeastern edge of the Sichuan basin has long been prone to earthquakes because it is bordered by a large, active fault. But the fracking is happening further to the south and east, where natural earthquakes are rare.

"It used to be a very stable region," said Yang.

Researchers in the U.S. are taking note. No fracking-induced earthquakes in North America have exceeded magnitude 5 so far, and they may still be unlikely to do so, given differences in the local geology, said Brudzinski. But most are quite shallow, only about 2-4 km belowground.

In the past, said Brudzinski, researchers have debated whether there might be something about the fracking process itself that keeps earthquakes small, ensuring some measure of safety despite the shallow depth. The recent tragedies in China suggest that people shouldn't depend on that as a safeguard.

"To me, that has been sort of the most important aspect of what I've seen from China," said Brudzinski. "It suggests that, yes: We can have some larger-size events."

Editor’s Note: Yuen Yiu contributed additional reporting to this story.

Authorized news sources may reproduce our content.© American Institute of Physics

Author Bio

Nala Rogers is a staff writer and editor at Inside Science, where she covers the Earth and Creature beats. She has a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Utah and a graduate certificate in science communication from U.C. Santa Cruz. Before joining Inside Science, she wrote for diverse outlets including Science, Nature, the San Jose Mercury News, and Scientific American. In her spare time she likes to explore wilderness.

Earthquakes linked to fracking cause controversy in China

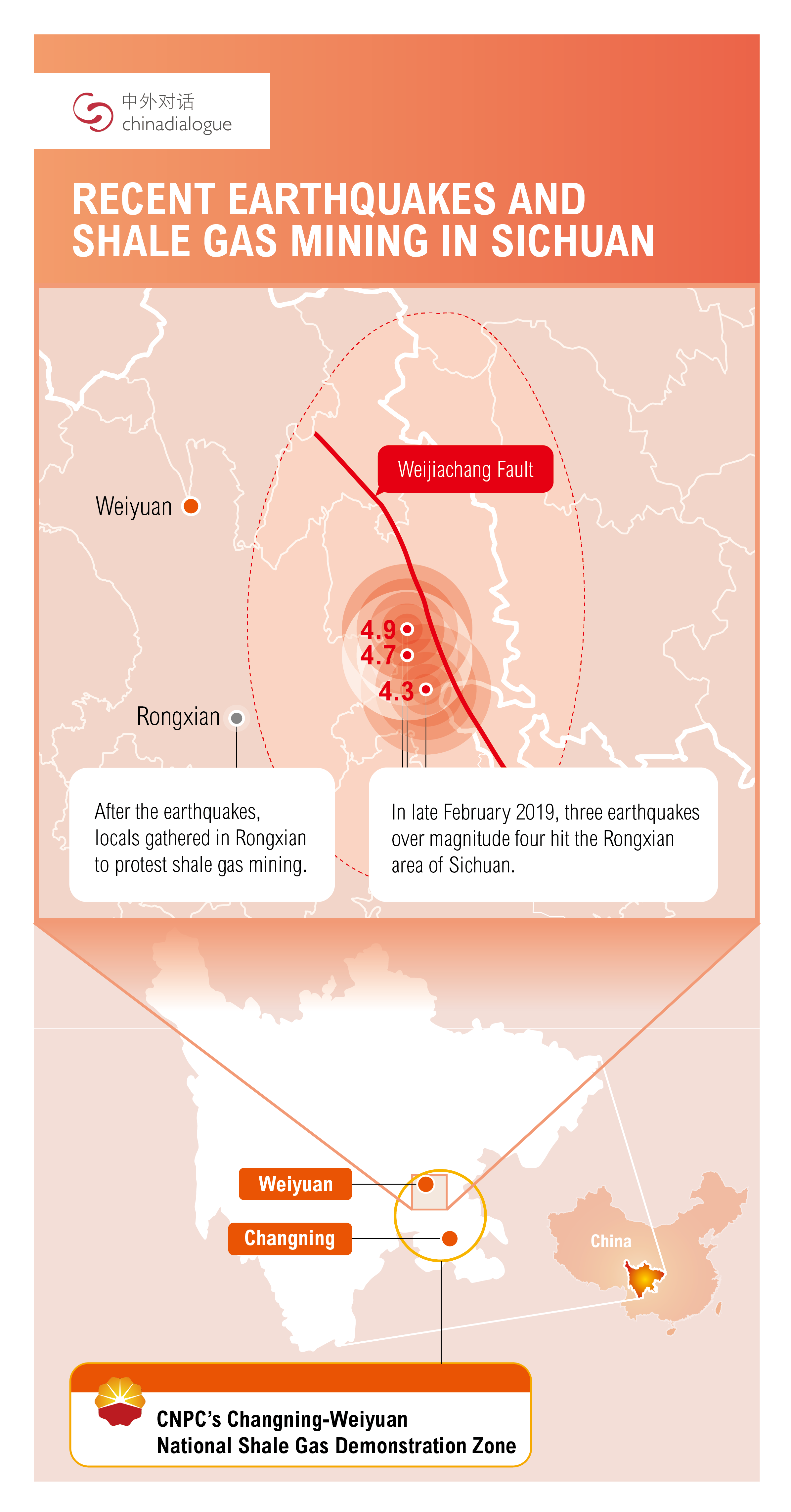

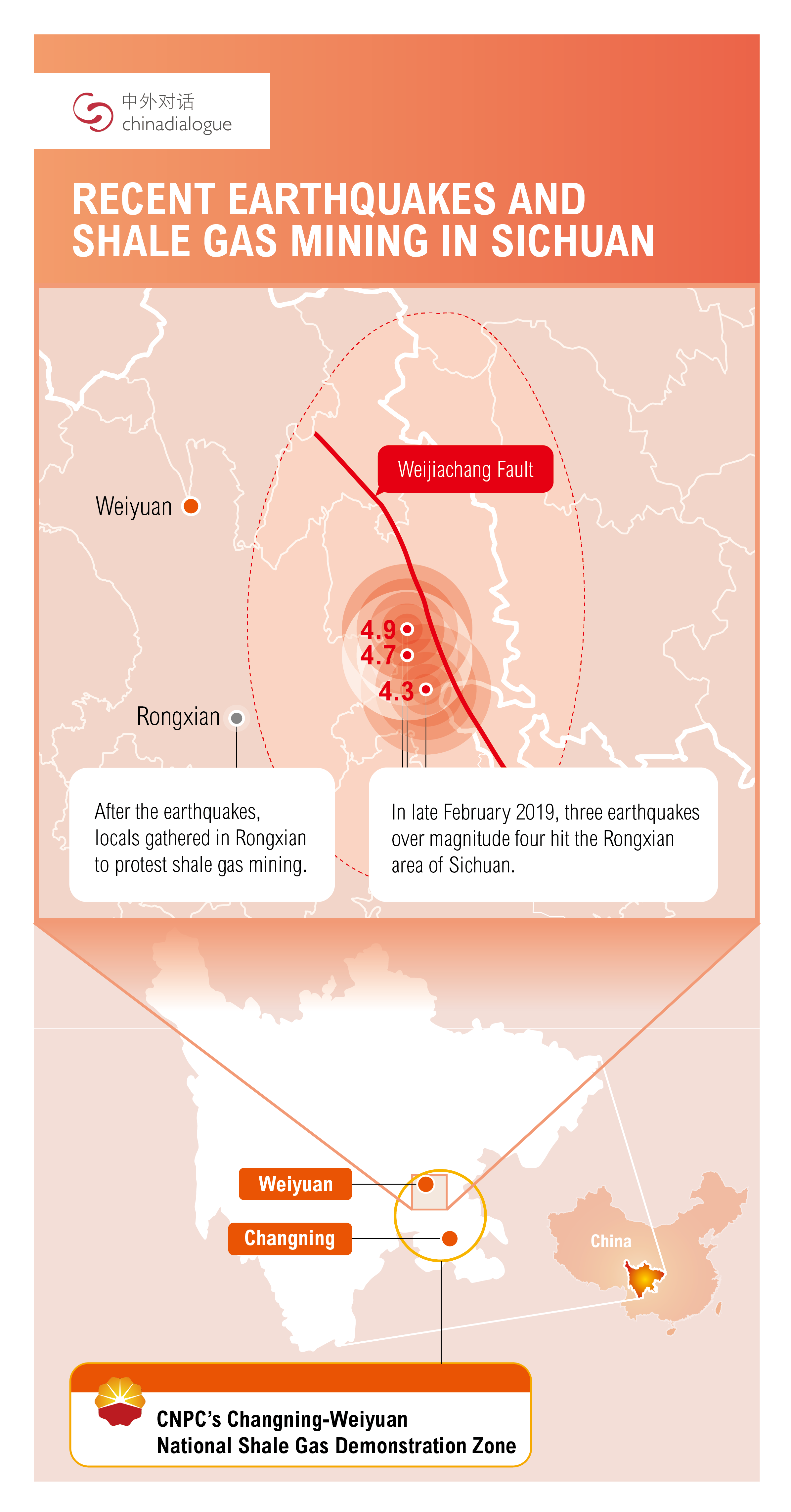

Protests against shale gas mining sparked by the Rongxian earthquakes unlikely to dent the sector, reports Feng Hao

Workers of a subsidiary of Sinopec, China's largest oil refiner, disassemble facilities after a trial operation in Chongqing, south-west China (Image: Liu Chan/Xinhua)

China’s shale gas industry has been shaken by controversy after three earthquakes in Sichuan province.

The earthquakes, all with a magnitude of over four, hit Rongxian near the city of Zigong on the 24th and 25th of February. They killed two people, injured 12 and damaged numerous buildings. Locals suspect shale gas extraction was to blame, and according to the local government, about 3,000 people gathered in Rongxian to protest the practice shortly after the earthquakes hit.

On the 25th the local government instructed shale gas firms to temporarily halt operations for the sake of what they called “earthquake safety”. There has been no word as yet on when extraction will start again.

Shale gas mining has proved highly controversial worldwide due to its potential safety risks and environmental impacts. Although the public response in China has not been equivalent, February’s protests are a sign of how high feelings run. Nevertheless, experts say this is unlikely to reduce the ambitions of government and businesses.

Cleaner energy

Market demand is behind China’s increased efforts to find and extract shale gas.

Shale gas is referred to as an unconventional natural gas, but it is effectively the same fuel. A cleaner and lower-carbon option than coal, natural gas is viewed as a transitional source of energy as the mix of energy changes to tackle air pollution and climate change. As a result, it has seen rocketing demand. In 2017 demand for natural gas outstripped supply by 4.8 billion cubic metres in northern China (where need is higher due to heating demand) and 11.3 billion cubic metres nationwide.

Na Min, chief information officer with BSC Energy, said: “Shortages naturally mean more capital flowing into the shale gas sector, encouraging upstream companies to prospect and increase output.” According to the firm’s calculations, China’s demand for natural gas will continue to grow in 2020.

The earthquakes, all with a magnitude of over four, hit Rongxian near the city of Zigong on the 24th and 25th of February. They killed two people, injured 12 and damaged numerous buildings. Locals suspect shale gas extraction was to blame, and according to the local government, about 3,000 people gathered in Rongxian to protest the practice shortly after the earthquakes hit.

On the 25th the local government instructed shale gas firms to temporarily halt operations for the sake of what they called “earthquake safety”. There has been no word as yet on when extraction will start again.

Shale gas mining has proved highly controversial worldwide due to its potential safety risks and environmental impacts. Although the public response in China has not been equivalent, February’s protests are a sign of how high feelings run. Nevertheless, experts say this is unlikely to reduce the ambitions of government and businesses.

Cleaner energy

Market demand is behind China’s increased efforts to find and extract shale gas.

Shale gas is referred to as an unconventional natural gas, but it is effectively the same fuel. A cleaner and lower-carbon option than coal, natural gas is viewed as a transitional source of energy as the mix of energy changes to tackle air pollution and climate change. As a result, it has seen rocketing demand. In 2017 demand for natural gas outstripped supply by 4.8 billion cubic metres in northern China (where need is higher due to heating demand) and 11.3 billion cubic metres nationwide.

Na Min, chief information officer with BSC Energy, said: “Shortages naturally mean more capital flowing into the shale gas sector, encouraging upstream companies to prospect and increase output.” According to the firm’s calculations, China’s demand for natural gas will continue to grow in 2020.

Strong growth in demand for natural gas has also caused reliance on imported gas to escalate, with policymakers becoming concerned about energy security. In September 2018 the State Council published its first document promoting development of the natural gas industry, instructing domestic oil and gas firms to increase prospecting and development funding to boost output and reserves.

Li Rong, chief public sector researcher with Cinda Securities, said there is little chance of natural gas discoveries being made in China in the near term, so any breakthroughs will have to come from unconventional sources: shale gas, tight gas and coalbed methane. “Future increases in domestic gas production will mainly come from unconventional sources, such as shale gas,” she said.

A growth bottleneck

But China’s shale gas ambitions predate the recent leap in demand for natural gas.

Shale gas extraction started in the United States, where technological improvements in the early 2000s led to rapid expansion, making the country much less reliant on energy imports. China is now looking to the US and hoping to replicate that success. According to estimates from the US Energy Information Administration, China has more shale gas reserves than any other nation – using current technology, its recoverable reserves are 68% larger than those of the US. China hopes this will provide energy self-sufficiency.

China’s Ministry of Land and Resources started investigating shale gas resources in 2004 and the first exploratory well was drilled in 2009.

2012 saw an ambitious five-year plan for shale gas development, with a production target of 6.5 billion cubic metres per year for 2015, and a subsidy of 0.4 yuan (US$0.06) per cubic metre for shale gas firms between 2012 and 2015. But by 2015 production stood at only 4.5 billion cubic metres per year, with only the two state-owned oil and gas giants, CNPC and Sinopec, running commercial operations.

BSC Energy’s Na Min says that further increases in output are being held back by bottlenecks in the prospecting and commercialisation process.

The Sichuan basin, where the recent earthquakes occurred, is one of China’s three richest natural gas basins and currently the most suitable for drilling. But reserves are deeper compared with the US, and the geology is more complex. That means technology used at one well may not be useful at another, even when its nearby, making prospecting and extraction more challenging and costs harder to control. The area is also densely populated, and intensive drilling could ferment public discontent.

The wells are already unpopular with local people. Tan Huimin, associate professor at Southwest University of Finance and Economics, conducted in-depth interviews with residents of the Sichuan county of Weiyuan in 2016. She found many were deeply concerned about water and air pollution, especially close to mining activities.

Despite this, the current five-year plan for shale gas has raised production targets again: “Assuming policy support is in place and market conditions are favourable, strive for annual shale gas production of 30 billion cubic metres by 2020.” This is lower than a pre-2015 target for 2020 of 60-100 billion cubic metres, but ongoing subsidies and tax breaks show that China still has high hopes for shale gas.

Earthquake worries

One of the main reasons members of the public oppose shale gas extraction is the link with earthquakes. This is especially so in Sichuan, where memories of the 2008 earthquake that killed over 69,000 people are still raw.

The gas is found in layers of shale rock, and hydraulic fracturing – the high-pressure pumping of water, sand and chemicals into the rock formation – is necessary to extract it, by enlarging cracks and allowing the gas to escape. This creates a lot of contaminated wastewater, which is often dealt with by injecting it into deep disposal wells.

Although the whole process is controversial, for both safety and environmental reasons, it is the injection of this wastewater that is thought to trigger earthquakes. In 2013 the US Geological Survey published research in Science saying “several of the largest earthquakes in the U.S. midcontinent in 2011 and 2012 may have been triggered by nearby disposal wells”.

The epicentres of February’s earthquakes were all about eight kilometres from Rongxian, right in the middle of CNPC’s Changning-Weiyuan National Shale Gas Demonstration Zone.

Despite this, some experts say it is hard to draw a direct link between the earthquakes and shale gas extraction in the region. Zhang Jianqiang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Chengdu Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, explained that the epicentres lay five kilometres beneath the surface, some distance from the deepest fracking at about 3.4 kilometres. Zhang claimed that a causal relation could therefore be eliminated, although further research would be necessary. He made no reference to wastewater disposal wells.

According to Tian Bingwei, associate professor at the Sichuan University – Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institute for Disaster Management, this area is prone to seismic activity. There have been five earthquakes of magnitude four or above within a 50-kilometre radius of February’s epicentres since monitoring began in 1970, a relatively high number.

But there are also other concerns about fracking, such as the huge quantities of water used. According to research from the World Resources Institute, 61% of China’s shale gas reserves are in areas under high levels of water stress. But WRI researcher Luo Tianyi argued that Sichuan lies in the Yangtze River basin so has more water available than many other areas. As such, it shouldn’t suffer increased water stress, but there may be localised competition for water in the short-term, he said.

Unshakeable ambition

On 4 March during the Two Sessions, China’s biggest annual political meetings, CNPC chairman and delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Yilin said in an interview that his corporation plans to produce 12 billion cubic metres of shale gas annually by 2020, and to double that to 24 billion cubic metres by 2025. This was only a week after the earthquake protests in Rongxian.

Sichuan is a focus for that expansion. In 2018 CNPC drilled 330 new operational wells in the Sichuan Basin – nearly 60% more than the total number of wells the company had in production by the end of 2017 (about 210).

Experts interviewed by chinadialogue generally agreed that the controversy over the earthquakes will not reduce the market and energy security ambitions of the shale gas sector and the government. But they said it will be necessary to address the discontent of residents and avoid putting the public at risk.

Li Rong of Cinda Securities said there should be a full scientific review of the risks of shale gas mining to ensure the safety of locals and their homes. She also suggested that during mining or well drilling, seismologists should be employed to monitor any links with earthquakes, and during initial site selection, seismic risks should be an essential part of environmental impact assessments.

Commenting on the huge quantities of water used, the WRI’s Luo Tianyi said that mining firms need to plan when and how they mine in line with seasonal water availability, local hydrology, and local demand for water.

Li Rong, chief public sector researcher with Cinda Securities, said there is little chance of natural gas discoveries being made in China in the near term, so any breakthroughs will have to come from unconventional sources: shale gas, tight gas and coalbed methane. “Future increases in domestic gas production will mainly come from unconventional sources, such as shale gas,” she said.

A growth bottleneck

But China’s shale gas ambitions predate the recent leap in demand for natural gas.

Shale gas extraction started in the United States, where technological improvements in the early 2000s led to rapid expansion, making the country much less reliant on energy imports. China is now looking to the US and hoping to replicate that success. According to estimates from the US Energy Information Administration, China has more shale gas reserves than any other nation – using current technology, its recoverable reserves are 68% larger than those of the US. China hopes this will provide energy self-sufficiency.

China’s Ministry of Land and Resources started investigating shale gas resources in 2004 and the first exploratory well was drilled in 2009.

2012 saw an ambitious five-year plan for shale gas development, with a production target of 6.5 billion cubic metres per year for 2015, and a subsidy of 0.4 yuan (US$0.06) per cubic metre for shale gas firms between 2012 and 2015. But by 2015 production stood at only 4.5 billion cubic metres per year, with only the two state-owned oil and gas giants, CNPC and Sinopec, running commercial operations.

BSC Energy’s Na Min says that further increases in output are being held back by bottlenecks in the prospecting and commercialisation process.

The Sichuan basin, where the recent earthquakes occurred, is one of China’s three richest natural gas basins and currently the most suitable for drilling. But reserves are deeper compared with the US, and the geology is more complex. That means technology used at one well may not be useful at another, even when its nearby, making prospecting and extraction more challenging and costs harder to control. The area is also densely populated, and intensive drilling could ferment public discontent.

The wells are already unpopular with local people. Tan Huimin, associate professor at Southwest University of Finance and Economics, conducted in-depth interviews with residents of the Sichuan county of Weiyuan in 2016. She found many were deeply concerned about water and air pollution, especially close to mining activities.

Despite this, the current five-year plan for shale gas has raised production targets again: “Assuming policy support is in place and market conditions are favourable, strive for annual shale gas production of 30 billion cubic metres by 2020.” This is lower than a pre-2015 target for 2020 of 60-100 billion cubic metres, but ongoing subsidies and tax breaks show that China still has high hopes for shale gas.

Earthquake worries

One of the main reasons members of the public oppose shale gas extraction is the link with earthquakes. This is especially so in Sichuan, where memories of the 2008 earthquake that killed over 69,000 people are still raw.

The gas is found in layers of shale rock, and hydraulic fracturing – the high-pressure pumping of water, sand and chemicals into the rock formation – is necessary to extract it, by enlarging cracks and allowing the gas to escape. This creates a lot of contaminated wastewater, which is often dealt with by injecting it into deep disposal wells.

Although the whole process is controversial, for both safety and environmental reasons, it is the injection of this wastewater that is thought to trigger earthquakes. In 2013 the US Geological Survey published research in Science saying “several of the largest earthquakes in the U.S. midcontinent in 2011 and 2012 may have been triggered by nearby disposal wells”.

The epicentres of February’s earthquakes were all about eight kilometres from Rongxian, right in the middle of CNPC’s Changning-Weiyuan National Shale Gas Demonstration Zone.

Despite this, some experts say it is hard to draw a direct link between the earthquakes and shale gas extraction in the region. Zhang Jianqiang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Chengdu Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, explained that the epicentres lay five kilometres beneath the surface, some distance from the deepest fracking at about 3.4 kilometres. Zhang claimed that a causal relation could therefore be eliminated, although further research would be necessary. He made no reference to wastewater disposal wells.

According to Tian Bingwei, associate professor at the Sichuan University – Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institute for Disaster Management, this area is prone to seismic activity. There have been five earthquakes of magnitude four or above within a 50-kilometre radius of February’s epicentres since monitoring began in 1970, a relatively high number.

But there are also other concerns about fracking, such as the huge quantities of water used. According to research from the World Resources Institute, 61% of China’s shale gas reserves are in areas under high levels of water stress. But WRI researcher Luo Tianyi argued that Sichuan lies in the Yangtze River basin so has more water available than many other areas. As such, it shouldn’t suffer increased water stress, but there may be localised competition for water in the short-term, he said.

Unshakeable ambition

On 4 March during the Two Sessions, China’s biggest annual political meetings, CNPC chairman and delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Yilin said in an interview that his corporation plans to produce 12 billion cubic metres of shale gas annually by 2020, and to double that to 24 billion cubic metres by 2025. This was only a week after the earthquake protests in Rongxian.

Sichuan is a focus for that expansion. In 2018 CNPC drilled 330 new operational wells in the Sichuan Basin – nearly 60% more than the total number of wells the company had in production by the end of 2017 (about 210).

Experts interviewed by chinadialogue generally agreed that the controversy over the earthquakes will not reduce the market and energy security ambitions of the shale gas sector and the government. But they said it will be necessary to address the discontent of residents and avoid putting the public at risk.

Li Rong of Cinda Securities said there should be a full scientific review of the risks of shale gas mining to ensure the safety of locals and their homes. She also suggested that during mining or well drilling, seismologists should be employed to monitor any links with earthquakes, and during initial site selection, seismic risks should be an essential part of environmental impact assessments.

Commenting on the huge quantities of water used, the WRI’s Luo Tianyi said that mining firms need to plan when and how they mine in line with seasonal water availability, local hydrology, and local demand for water.

No comments:

Post a Comment