Kalispell residents recall eerie aftermath of volcanic eruption

IN THE AGE OF COVID-19 SARS CORONAVIRUS

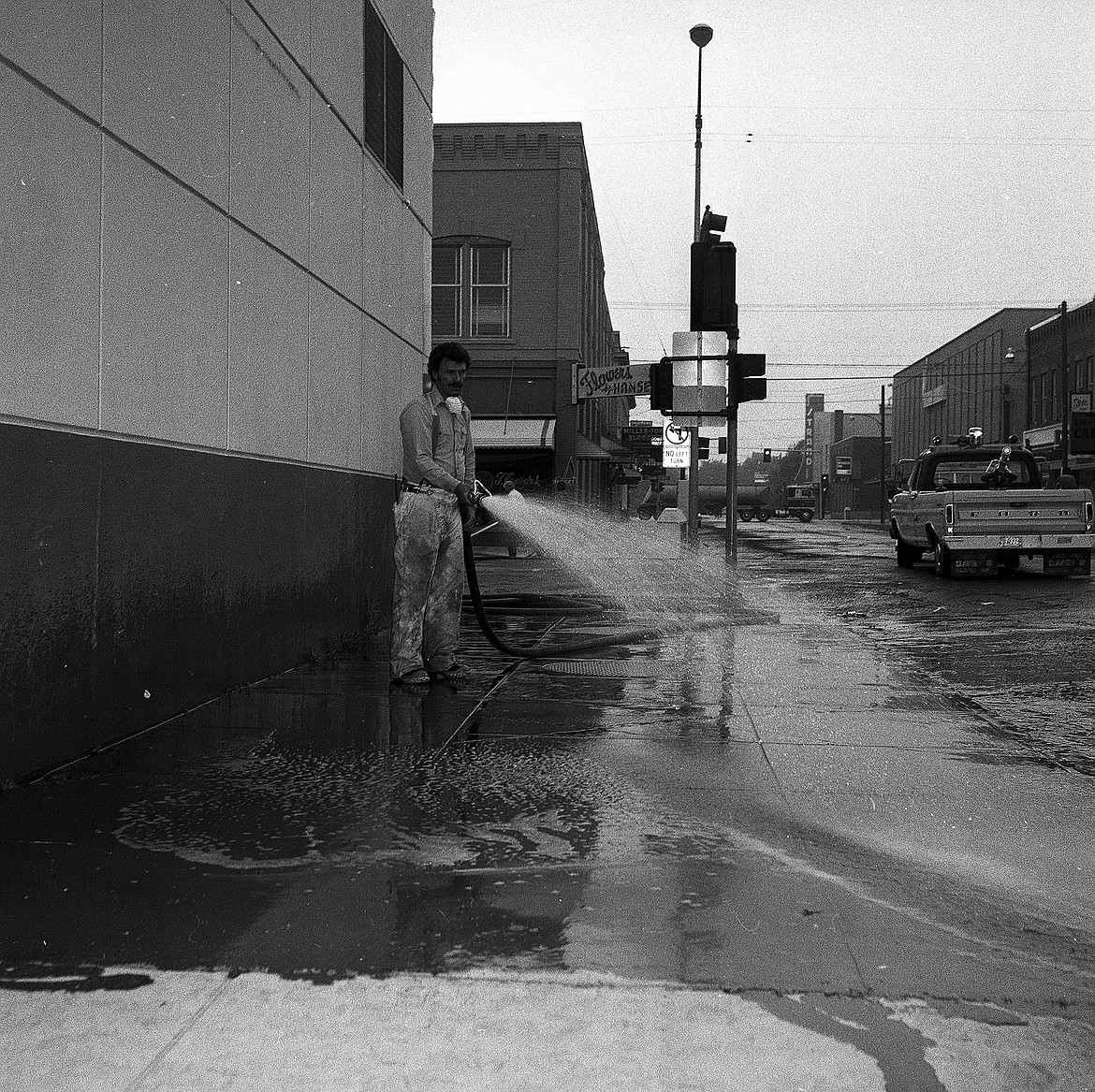

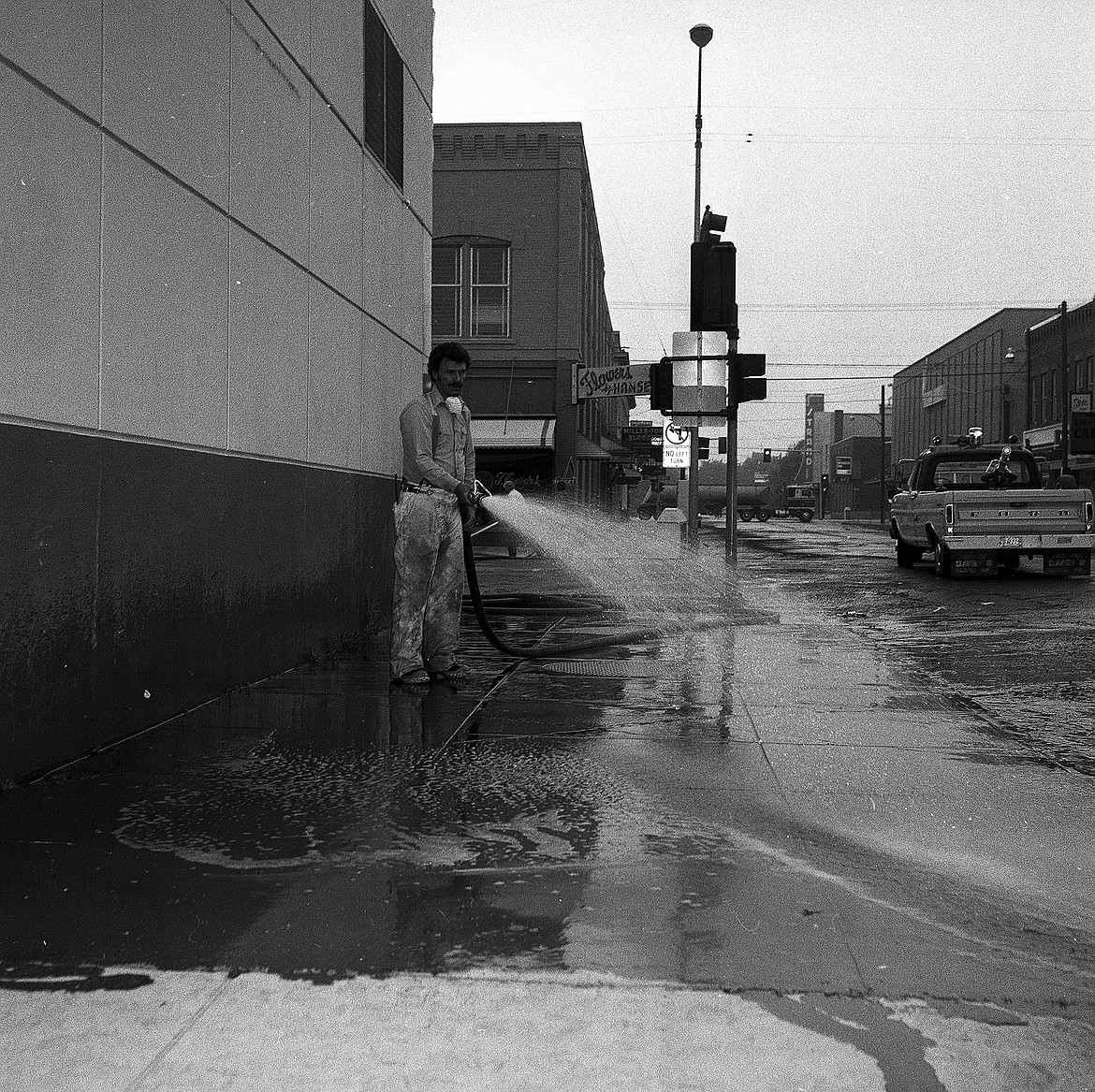

A man hoses ash off the sidewalk in front of Conrad National Bank

in Kalispell in this Daily Inter Lake file photo.By Jeremy Weber

By Jeremy Weber Daily Inter Lake---Kalispell, Montana | April 12, 2020

Annie McLaughlin of Whitefish was six months pregnant and headed to work at the Roundup (now the Town Pump) in Whitefish when she saw the ash cloud moving in from the catastrophic Mount St. Helens volcanic eruption.

“It was warm and still and the sky began to turn yellow. I have been in tornadoes before and it reminded me a lot of those kind of skies,” she said. “It was pretty eerie. We woke up the next morning to 3 inches of ash everywhere.”

In an eerie mirror of recent events spurred by the coronavirus pandemic, all but the essential businesses in the Flathead Valley were closed for three days while residents were advised to wear masks if they left their homes. With gas stations deemed essential businesses, McLaughlin returned to work the next day, mask and all.

Jim Oliverson of Kalispell was in Bozeman when he heard about the eruption that fateful day in 1980. Then 41, Oliverson was attending a CEO meeting as the administrator of St. Luke’s Hospital in Ronan. When someone came in and told the group that Mount St. Helens had erupted, Oliverson admits that didn’t mean much to him. It was not until later that evening that he began to understand the magnitude of the situation.

“I remember turning a TV on and seeing a reporter from one of the Missoula stations standing in the middle of an abandoned street in what looked like a snowstorm, but it was ash,” he recalled. “It was so odd.”

Oliverson soon learned what kind of impact the ash fallout was having after he returned to work in Ronan.

“I had to call the maintenance guy and make sure he babysat those air-conditioning systems and changed the air filters as often as he had to. I told him not to throw the old ones away because I thought we might have to clean them and reuse them,” he said. “Nobody knew for sure how long the falling ash was going to last.”

Oliverson said the reaction was strikingly similar to what is happening today with COVID-19.

“Nobody really knew what was going to happen. Human beings, being as predictable as we are, did pretty much what we are seeing now. Everyone was going down to the grocery store and stocking up on everything they could. People were frightened and they didn’t know what to expect,” he said. “There were people saying you had to wear a mask to go outside. There were others saying a bandanna was alright, if [it was wet]. Other people were warning that wetting the bandanna was dangerous because it turned the ash more solid. There was a lot of panic going around.”

For Chris Dasios of Troy, then a senior at Eastern Washington University in Cheney, that Sunday morning started with a deep sense of dread. No, he was not worried about a possible eruption of the volcano 235 miles to the southwest. Dasios was worried about the set of final tests that stood between him and graduation. After an all-night cramming session, complete with coffee and NoDoz, Dasios was convinced all was lost. Needing to clear his mind, Dasios took the elevator to the ground floor of the 11-story Dressler Hall and walked outside. He was not ready for what awaited him.

“All of a sudden, a rolling, boiling black cloud came in from the west. I thought ‘God help us, what is that?’ We were told to go back to our dorms and apartments as the ash started falling all around us,” he recalled.

IT WAS an event unlike any other seen in the United States up until that time and is still the most destructive volcanic eruption in the nation’s history. Final estimates placed damages at $1.1 billion ($3.5 billion today) with the destruction of 200 houses, 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways and 185 miles of highway. In the first nine hours of eruption, an estimated 540 million tons of ash fell over more than 22,000 square miles.

Stories in the May 19, 1980, edition of the Daily Inter Lake reported all schools in Northwest Montana closed. Glacier Park International Airport canceled all commercial flights and mail delivery was canceled. Roads were open to emergency traffic only as the ash could easily cause severe damage to vehicles. Residents were advised to stay inside if they could, or wear a mask if they couldn’t.

As destructive as it was, the eruption did provide a silver lining for some. McLaughlin recalled never having a better garden than she did that year.

Dasios actually credits the eruption for his graduation from college.

“After I found out what was going on, I studied up. I stopped partying for a while and got ready and when classes started back up I passed my finals and graduated in June with a major in history and a minor in sociology in June,” he said with a laugh. “I am proud to say the eruption actually helped me. I’m not sure how many people can say that.”

Ash from the May 18, 1980, eruption left many areas in the Flathead covered in ash. (USGS photo)

Annie McLaughlin of Whitefish was six months pregnant and headed to work at the Roundup (now the Town Pump) in Whitefish when she saw the ash cloud moving in from the catastrophic Mount St. Helens volcanic eruption.

“It was warm and still and the sky began to turn yellow. I have been in tornadoes before and it reminded me a lot of those kind of skies,” she said. “It was pretty eerie. We woke up the next morning to 3 inches of ash everywhere.”

In an eerie mirror of recent events spurred by the coronavirus pandemic, all but the essential businesses in the Flathead Valley were closed for three days while residents were advised to wear masks if they left their homes. With gas stations deemed essential businesses, McLaughlin returned to work the next day, mask and all.

Jim Oliverson of Kalispell was in Bozeman when he heard about the eruption that fateful day in 1980. Then 41, Oliverson was attending a CEO meeting as the administrator of St. Luke’s Hospital in Ronan. When someone came in and told the group that Mount St. Helens had erupted, Oliverson admits that didn’t mean much to him. It was not until later that evening that he began to understand the magnitude of the situation.

“I remember turning a TV on and seeing a reporter from one of the Missoula stations standing in the middle of an abandoned street in what looked like a snowstorm, but it was ash,” he recalled. “It was so odd.”

Oliverson soon learned what kind of impact the ash fallout was having after he returned to work in Ronan.

“I had to call the maintenance guy and make sure he babysat those air-conditioning systems and changed the air filters as often as he had to. I told him not to throw the old ones away because I thought we might have to clean them and reuse them,” he said. “Nobody knew for sure how long the falling ash was going to last.”

Oliverson said the reaction was strikingly similar to what is happening today with COVID-19.

“Nobody really knew what was going to happen. Human beings, being as predictable as we are, did pretty much what we are seeing now. Everyone was going down to the grocery store and stocking up on everything they could. People were frightened and they didn’t know what to expect,” he said. “There were people saying you had to wear a mask to go outside. There were others saying a bandanna was alright, if [it was wet]. Other people were warning that wetting the bandanna was dangerous because it turned the ash more solid. There was a lot of panic going around.”

For Chris Dasios of Troy, then a senior at Eastern Washington University in Cheney, that Sunday morning started with a deep sense of dread. No, he was not worried about a possible eruption of the volcano 235 miles to the southwest. Dasios was worried about the set of final tests that stood between him and graduation. After an all-night cramming session, complete with coffee and NoDoz, Dasios was convinced all was lost. Needing to clear his mind, Dasios took the elevator to the ground floor of the 11-story Dressler Hall and walked outside. He was not ready for what awaited him.

“All of a sudden, a rolling, boiling black cloud came in from the west. I thought ‘God help us, what is that?’ We were told to go back to our dorms and apartments as the ash started falling all around us,” he recalled.

IT WAS an event unlike any other seen in the United States up until that time and is still the most destructive volcanic eruption in the nation’s history. Final estimates placed damages at $1.1 billion ($3.5 billion today) with the destruction of 200 houses, 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways and 185 miles of highway. In the first nine hours of eruption, an estimated 540 million tons of ash fell over more than 22,000 square miles.

Stories in the May 19, 1980, edition of the Daily Inter Lake reported all schools in Northwest Montana closed. Glacier Park International Airport canceled all commercial flights and mail delivery was canceled. Roads were open to emergency traffic only as the ash could easily cause severe damage to vehicles. Residents were advised to stay inside if they could, or wear a mask if they couldn’t.

As destructive as it was, the eruption did provide a silver lining for some. McLaughlin recalled never having a better garden than she did that year.

Dasios actually credits the eruption for his graduation from college.

“After I found out what was going on, I studied up. I stopped partying for a while and got ready and when classes started back up I passed my finals and graduated in June with a major in history and a minor in sociology in June,” he said with a laugh. “I am proud to say the eruption actually helped me. I’m not sure how many people can say that.”

For Oliverson, recent events have brought memories of Mount St. Helens to mind. He still finds himself thinking about the destruction the mountain caused that day.

“Not long after the eruption, I found myself at an intersection where I could see a mile to my left and a mile straight ahead of me. I looked at that and tried to imagine a mile straight above me, because they had said that when the volcano blew that it took a cubic mile of mountain with it. That was just a numbing thought for me. It still is,” he said.

“I am feeling some of the same feeling now as I did back then because we really don’t know how long this crisis with COVID-19 is going to last."

“Back then, we didn’t know how dangerous the ash from Mount St. Helens was. Because we didn’t know then and we don’t know now, it is very similar,” he said. “We had no control over it and everyone was waiting for the federal government to do something. We just have to ride it out today like we did back then.”

Ash from the May 18, 1980, eruption left many areas in the Flathead covered in ash. (USGS photo)

Ash covers a farm in Connelll, Wash. 180 miles from Mount St. Helens. (Lyn Topink, NFS)

Ash clouds from Mount St. Helens move over Ephrata airport in Washington on Monday, May 19, 1980. Communities across central and eastern Washington were covered in 3-5 inches of gritty, fine, ash particles. (NFS photo)

Photo taken on May 18, 1980, of Mount St. Helens at about 3:30 pm. Jim Hughes took this from about 20 air miles away. (NFS photo)

The May 18, 1980, eruption of Mount St. Helens destroyed nearly a cubic mile of the top of the mountain. (USGS photo)

A Daily Inter Lake file photo shows a man selling masks, as protection from volcanic ash, out of his truck.

No comments:

Post a Comment