Lungfish cocoon found to be living antimicrobial tissue

A team of researchers from the University of New Mexico, the University of California and the University of Murcia has found that the cocoon created by lungfish living in dry lakebeds in Africa is made of living antimicrobial tissue. They've published the results of their study in the journal Science Advances.

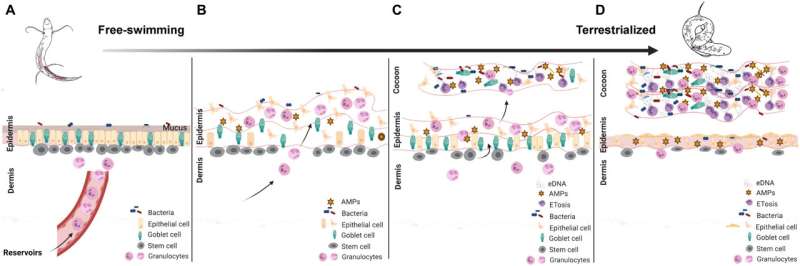

Lungfish live in parts of Africa in small lakes that tend to go dry when it does not rain for a long time. When this happens, the lungfish create a cocoon around themselves using mucus. The purpose of the cocoon is to protect the lungfish from drying out as it waits for wetter conditions to return. In this new effort, the researchers have found that there is more to the cocoon than previously thought.

Until now, researchers believed the cocoon was simply a shell casing of sorts, with no purpose other than to prevent moisture from escaping under the hot African sun. Now, it appears the cocoon is not only alive, but is made of antimicrobial tissue.

To learn more about the lungfish and its cocoon, the researchers began an analysis of its makeup in 2018. They found granulocyte (white blood cell) markers that migrated during the time when the lungfish was waiting for water to return. More recently, the team has taken a closer look and found that the cocoon was chock full of granulocytes. They also found that they migrated from the skin into the cocoon on a slow, continual basis—a finding that showed the cocoon was much more than just dry mucus; it was a living part of the lungfish.

Imaging showed the granulocytes create traps that immobilize bacteria. When the researchers removed such traps from several specimens, they found the lungfish became susceptible to skin infections and circulating bacteria that are known to lead to septicemia. They also found that some of the infections led to hemorrhage. The researchers suggest that the cocoon protects the lungfish from more than just heat and sun—it also protects them from infections.

Fossil expands ancient fish family tree

More information: Ryan Darby Heimroth et al, The lungfish cocoon is a living tissue with antimicrobial functions, Science Advances (2021). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abj0829

Journal information: Science Advances

© 2021 Science X Network

No comments:

Post a Comment