At a time when Black actors were forced into submissive or inarticulate roles, the actor showed strength moving through hostile white spaces with dignity

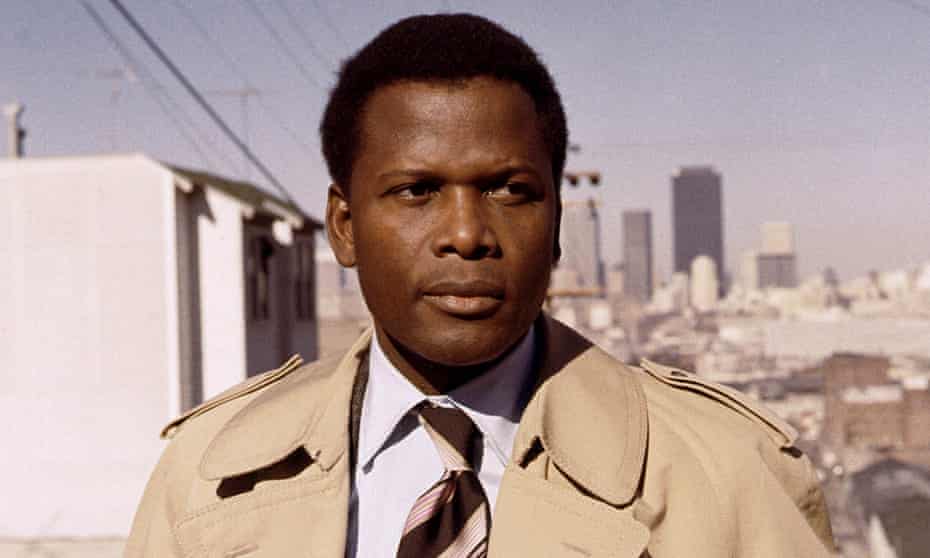

Sidney Poitier in They Call Me Mister Tibbs!

Photograph: United Artists/Allstar

Todd Boyd

Tue 11 Jan 2022

Upon the announcement of Hollywood legend Sidney Poitier’s death, I sent out a tweet that featured my favorite photo of him. The photo in question shows a shirtless Poitier, wearing dark sunglasses like Miles Davis on the cover of ’Round About Midnight, playing the saxophone alongside jazz man Sonny Stitt, while standing in the street, surrounded by a community of appreciative onlookers, otherwise known as “the people”. The reason I dig this photo so much is because it offers a more complex image of Poitier than the one that had come to define him at the height of his fame in Hollywood. I have never been able to confirm the context of this photo, but I have always assumed that it was taken while he was preparing for his role as the expatriate horn player in the film Paris Blues. Whatever the circumstances, though, the image itself suggests an authenticity, a certain street credibility that is much more complex than the conveniently integrationist symbolism that his persona has so often been reduced to.

Sidney Poitier’s defiance, grace and style changed me – and shaped my life as an actor

David Harewood

By the late 1960s Sidney Poitier was the biggest box office draw in America. With movies like In the Heat of the Night, To Sir With Love and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, his films had become their own genre. Accomplishing this was no small feat. When Poitier began his career, most movies featuring predominantly Black casts were musicals. Black men who appeared in otherwise all-white films tended to be represented as inarticulate, child-like buffoons; racial clowns who scratched when they didn’t itch and laughed when nothing was funny. Poitier’s rise to the top of the Hollywood mountain changed this. He was often the lone Black person moving through hostile white spaces. His refined, erudite and dignified image was a counter to the coonery and buffoonery that figures like Stepin’ Fetchit, Mantan Moreland, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and Willie Best had previously represented. Like so many elite mid-century jazz musicians, Poitier wanted people to see him as an artist, not as a stereotypical entertainer. And in this he succeeded.

When perhaps his most famous character, Virgil Tibbs from In the Heat of the Night, demanded that the racist southern white cops put some respect on his name, “They call me Mister Tibbs!” Poitier was like Muhammad Ali who had demanded the same thing in the ring and in real life. In the film, the character of Endicott took offense to the fact that the “uppity” Tibbs had actually spoken to him as an equal, instead of like the fawning obsequious fool that he expected him to be. So, Endicott slaps Tibbs across the face for getting out of what he perceived to be his place. But quicker than the blink of an eye, Tibbs responded in kind, slapping the taste out of Endicott’s mouth, as it were. The “slap heard round the world” – this legendary cinematic moment when Poitier’s stardom afforded his character the opportunity to retaliate against a white man without fear of retribution – demonstrated that just because he was known for playing these proper gentlemen on screen, he could still handle his business, if need be.

Poitier’s image in film has often been associated with that of Dr Martin Luther King Jr; Poitier won the Academy Award for best actor the same year that King won the Nobel prize. But in this instance, when Tibbs slapped Endicott back, the character that he would most be associated with demonstrated that there were multiple layers to his complex persona. He may have reminded some of MLK, but in the late 60s when the civil rights movement was being challenged by assertions of Black Power, Virgil Tibbs did not turn the other cheek. Here he had more in common with Malcolm X than he did with Dr King, despite what his measured persona may have lead some people to believe.

Seeing In the Heat of the Night as a kid left an indelible imprint on my adult mind. Being a distinguished gentleman did not mean accepting humiliation, literally or figuratively. Demanding that those celluloid racists respect him and showing them that he could maneuver in a variety of ways said to me that being well-rounded and multidimensional, defying categorization, mixing supreme intellect with authenticity was indeed the way to go. This is what Tibbs, Poitier’s larger cinematic persona, and especially that photo of him playing the sax in his shades, surrounded by Blackness, came to stand for.

Tue 11 Jan 2022

Upon the announcement of Hollywood legend Sidney Poitier’s death, I sent out a tweet that featured my favorite photo of him. The photo in question shows a shirtless Poitier, wearing dark sunglasses like Miles Davis on the cover of ’Round About Midnight, playing the saxophone alongside jazz man Sonny Stitt, while standing in the street, surrounded by a community of appreciative onlookers, otherwise known as “the people”. The reason I dig this photo so much is because it offers a more complex image of Poitier than the one that had come to define him at the height of his fame in Hollywood. I have never been able to confirm the context of this photo, but I have always assumed that it was taken while he was preparing for his role as the expatriate horn player in the film Paris Blues. Whatever the circumstances, though, the image itself suggests an authenticity, a certain street credibility that is much more complex than the conveniently integrationist symbolism that his persona has so often been reduced to.

Sidney Poitier’s defiance, grace and style changed me – and shaped my life as an actor

David Harewood

By the late 1960s Sidney Poitier was the biggest box office draw in America. With movies like In the Heat of the Night, To Sir With Love and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, his films had become their own genre. Accomplishing this was no small feat. When Poitier began his career, most movies featuring predominantly Black casts were musicals. Black men who appeared in otherwise all-white films tended to be represented as inarticulate, child-like buffoons; racial clowns who scratched when they didn’t itch and laughed when nothing was funny. Poitier’s rise to the top of the Hollywood mountain changed this. He was often the lone Black person moving through hostile white spaces. His refined, erudite and dignified image was a counter to the coonery and buffoonery that figures like Stepin’ Fetchit, Mantan Moreland, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and Willie Best had previously represented. Like so many elite mid-century jazz musicians, Poitier wanted people to see him as an artist, not as a stereotypical entertainer. And in this he succeeded.

When perhaps his most famous character, Virgil Tibbs from In the Heat of the Night, demanded that the racist southern white cops put some respect on his name, “They call me Mister Tibbs!” Poitier was like Muhammad Ali who had demanded the same thing in the ring and in real life. In the film, the character of Endicott took offense to the fact that the “uppity” Tibbs had actually spoken to him as an equal, instead of like the fawning obsequious fool that he expected him to be. So, Endicott slaps Tibbs across the face for getting out of what he perceived to be his place. But quicker than the blink of an eye, Tibbs responded in kind, slapping the taste out of Endicott’s mouth, as it were. The “slap heard round the world” – this legendary cinematic moment when Poitier’s stardom afforded his character the opportunity to retaliate against a white man without fear of retribution – demonstrated that just because he was known for playing these proper gentlemen on screen, he could still handle his business, if need be.

Poitier’s image in film has often been associated with that of Dr Martin Luther King Jr; Poitier won the Academy Award for best actor the same year that King won the Nobel prize. But in this instance, when Tibbs slapped Endicott back, the character that he would most be associated with demonstrated that there were multiple layers to his complex persona. He may have reminded some of MLK, but in the late 60s when the civil rights movement was being challenged by assertions of Black Power, Virgil Tibbs did not turn the other cheek. Here he had more in common with Malcolm X than he did with Dr King, despite what his measured persona may have lead some people to believe.

Seeing In the Heat of the Night as a kid left an indelible imprint on my adult mind. Being a distinguished gentleman did not mean accepting humiliation, literally or figuratively. Demanding that those celluloid racists respect him and showing them that he could maneuver in a variety of ways said to me that being well-rounded and multidimensional, defying categorization, mixing supreme intellect with authenticity was indeed the way to go. This is what Tibbs, Poitier’s larger cinematic persona, and especially that photo of him playing the sax in his shades, surrounded by Blackness, came to stand for.

Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger in In The Heat Of The Night.

Photograph: United Artists/Allstar

Many years after I initially saw Poitier in this groundbreaking film, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting him. In the late 1990s Poitier was the commencement speaker at the USC School of Cinematic Arts where I have spent the last 30 years of my professional life. Watching him as a kid, the lone Black man navigating labyrinthine white spaces, was comparable to the occupational life I found myself living in the rarified spaces of academia. Exhibiting a gentlemanly manner coexisted alongside an understanding that not everyone agreed that I actually belonged in such an elite space. Like Virgil Tibbs, I could be diplomatic, but as that hilarious malt liquor ad from the 1980s said, “Don’t let the smooth taste fool you.”

Standing on the graduation stage in full academic regalia, as I placed a PhD hood on a newly graduated doctoral candidate, thinking about how the people who created all of this higher education pomp and circumstance most certainly never imagined that a cat like me would be representing in this way, I turned around to see Poitier approaching me, with his hand extended, smiling broadly. His words, “Nice to meet you, Dr” echoed as I shook his hand. As we stood there, I absorbed the magnitude of the moment. He offered multiple compliments and pleasantries, as gracious in life as that of his persona. We shared a knowing laugh. But this was Sidney Poitier, not Virgil Tibbs. He understood what this all meant, and so did I. Things that are understood often need not be articulated.

Sidney Poitier was a giant of American culture. He stands as one of the most important figures in the history of Hollywood, without question. The monumental legacy of Poitier’s style is evident in those that he influenced. Be it the career of contemporary Hollywood royalty Denzel Washington, or that of the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama. Sidney Poitier, the distinguished gentleman of cinema was groundbreaking, inspirational, cool, complex and authentic as well. The era he represented is long gone, but the foundation he laid is one we’re still building on. Rest in power!

Dr Todd Boyd is the Katherine and Frank Price endowed chair for the study of race and popular culture at the USC School of Cinematic Arts

Many years after I initially saw Poitier in this groundbreaking film, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting him. In the late 1990s Poitier was the commencement speaker at the USC School of Cinematic Arts where I have spent the last 30 years of my professional life. Watching him as a kid, the lone Black man navigating labyrinthine white spaces, was comparable to the occupational life I found myself living in the rarified spaces of academia. Exhibiting a gentlemanly manner coexisted alongside an understanding that not everyone agreed that I actually belonged in such an elite space. Like Virgil Tibbs, I could be diplomatic, but as that hilarious malt liquor ad from the 1980s said, “Don’t let the smooth taste fool you.”

Standing on the graduation stage in full academic regalia, as I placed a PhD hood on a newly graduated doctoral candidate, thinking about how the people who created all of this higher education pomp and circumstance most certainly never imagined that a cat like me would be representing in this way, I turned around to see Poitier approaching me, with his hand extended, smiling broadly. His words, “Nice to meet you, Dr” echoed as I shook his hand. As we stood there, I absorbed the magnitude of the moment. He offered multiple compliments and pleasantries, as gracious in life as that of his persona. We shared a knowing laugh. But this was Sidney Poitier, not Virgil Tibbs. He understood what this all meant, and so did I. Things that are understood often need not be articulated.

Sidney Poitier was a giant of American culture. He stands as one of the most important figures in the history of Hollywood, without question. The monumental legacy of Poitier’s style is evident in those that he influenced. Be it the career of contemporary Hollywood royalty Denzel Washington, or that of the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama. Sidney Poitier, the distinguished gentleman of cinema was groundbreaking, inspirational, cool, complex and authentic as well. The era he represented is long gone, but the foundation he laid is one we’re still building on. Rest in power!

Dr Todd Boyd is the Katherine and Frank Price endowed chair for the study of race and popular culture at the USC School of Cinematic Arts

No comments:

Post a Comment