todayuknews

10 hours ago

At Lothian Pension Fund, caring about the climate involves an approach it calls “engage your equities, deny your debt”.

Lothian, one of Scotland’s largest public-sector pension funds with £8bn in assets under management, is not alone in seeking to engage with the companies in which it holds shares, on behalf of its investors and sponsors.

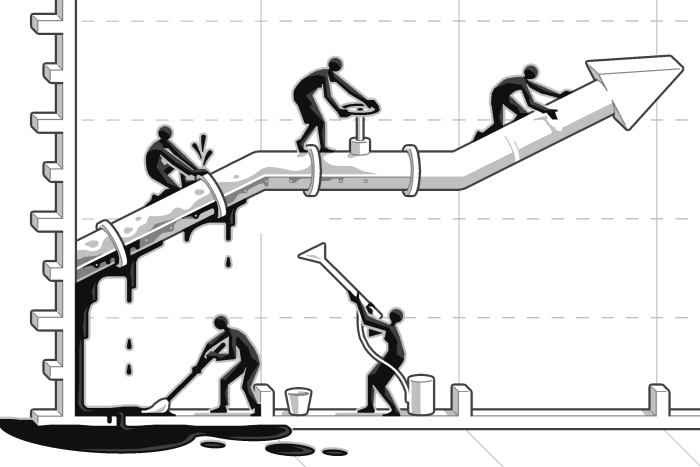

However, the idea of a dual approach — in which you deny new debt funding to companies with poor climate policies but do not sell shares in companies you can influence — is relatively novel. It liberates investors from the hotly debated but binary choice of: divest or engage?

Unlike divestment or engagement, denying companies the debt financing they need — in Lothian’s case by buying new bonds only if issuers’ strategies are aligned with the Paris climate agreement — has immediate consequences. “That has a genuine impact on the financial position of the corporate in question,” explains David Hickey, portfolio manager at Lothian, which holds about 60 per cent of its assets in equities and 20 per cent in debt.

On the equities side, the debate is still whether it is more effective to sell carbon-intensive stocks or retain them and push the companies — through discussions with management or shareholder resolutions — to work harder at emissions reduction.

Some investors have tried both. “Fossil fuel divestment has been a big topic of conversation over the years and we’ve done quite a bit of that,” says Brad Harrison, managing director at US wealth manager Tiedemann Advisors. “We’ve seen success with our third-party fund managers who are very active with the concept of shareholder engagement.”

Those backing engagement are now increasing in number. For example, investor group Climate Action 100+, which presses companies on carbon reduction, climate-related financial disclosures and governance, now represents 700 investors with more than $68tn in assets. Its members include Amundi, BlackRock, Fidelity International and Legal & General Investment Management.

They, and others, argue that divestment deprives investors of influence and transfers shares to owners who may care little about climate change. “By simply divesting from a company with a high carbon footprint, you’re decarbonising your portfolio but you’re not decarbonising the economy,” points out Fionna Ross, senior ESG analyst for US equities at asset manager Abrdn.

Added to this, fund managers also argue that mandatory divestment risks damaging the direct interests of their clients. This is among the reasons that the $319bn California State Teachers’ Retirement System (Calstrs) is pushing back against a California Senate bill that would prevent the pension fund from owning stakes in oil and gas producers.

Recommended

Those favouring engagement point to a range of tools that can be used to push companies in a more sustainable direction — from dialogue with corporate leaders to using shareholder votes to replace company managers or board members. In 2021, for example, activist fund Engine No. 1, which is focused on climate change, won three board seats at oil major ExxonMobil.

By contrast, the fossil fuel divestment movement argues that divestment is a more powerful strategy than engagement since it sends an important and highly public signal.

Divestment at scale stigmatises the fossil fuel sector and so makes it easier, politically, for legislators to introduce tough climate regulations, argues Richard Brooks, climate finance director at Canada-based campaign group Stand.earth. It is, he says, creating “the political space to pass climate policy, which is urgently needed”.

And the movement is achieving scale. In February, Stand.earth announced that investors committing to fossil fuel divestment represented $40tn of assets under management, up from $15tn a year earlier. The group tracks AUM, rather than amounts actually divested, since institutions’ divestment schedule is hard to follow. By citing AUM, the group is also speaking the language of the capital markets.

But, while arguments on how to coax business into curbing fossil fuel consumption and production continue, tangible results remain elusive. In fact, in 2021, energy-related carbon emissions reached historic highs, according to the International Energy Agency, bringing the world closer to the “point of no return” warned of by UN Secretary-General António Guterres in 2019.

How should investors clean up the world’s dirtiest companies?

Coming on May 31: The Moral Money Forum digs deeper into the arguments for divestment, engagement or new approaches that combine elements of both strategies

Those hoping for progress on political action to halt climate change have also been disappointed. The Climate Action Tracker project sees policy implementation advancing “at a snail’s pace” and describes national net zero targets for 2030 as “totally inadequate”.

Meanwhile, CA 100+ recently revealed that only 17 per cent of its “focus companies” — which include steel producers such as ArcelorMittal, cement producers such as Holcim and Cemex, oil and gas companies such as BP and Chevron and airlines such as Delta and American Airlines — had set medium-term targets consistent with keeping global warming to 1.5C.

Likewise, only 17 per cent had developed quantifiable strategies to reach their goals.

“I keep challenging people to show me an example where institutional investors engaging a fossil fuel company to reduce their emissions has actually led to a reduction,” says Brooks. “There isn’t yet an example of that.”

Catherine Howarth, chief executive of ShareAction, a responsible investment campaign group, believes that, for engagement to work, investors must stiffen their spines. “There’s still too little willingness among institutional investors to be challenging,” she says.

Howarth is among those who see debt denial as an effective strategy. “That could have a meaningful impact on the capital for these companies,” she argues.

There’s still too little willingness among institutional investors to be challenging

In 2019, for example, NatWest removed investment grade oil and gas debt from its portfolios as part of a policy of not funding the debt of companies not aligned with the bank’s net zero goals.

Debt is also a tool of influence when sustainability targets are built into financing facilities, says Jennifer Motles, chief sustainability officer at Philip Morris International.

She cites PMI’s issuance last year of a $2.5bn revolving credit facility that ties interest payments to targets for phasing cigarettes out of the business and penalises investors for missed milestones.

Fossil fuel companies, she suggests, could follow suit. “It’s the same idea as the decarbonisation of the value chain,” she says. “This the ‘decigarettisation’ of our company.”

Debt denial has yet to be widely adopted, though.

“There’s a little bit of it going on,” says Howarth. “But it’s not having either signalling power or much in the way of actual impact on the decision-making of finance directors of large high-carbon companies because it’s not happening at scale.”

Similarly, sustainability-linked bonds do not always include penalties or tough timeframes for companies to meet. “It’s a conceptual idea and has sounded nice but hasn’t really worked so far,” says Gillian de Candole, portfolio manager at Lothian.

However, de Candole and Hickey argue that, if designed with appropriate rigour, debt instruments could give investors powerful new sticks to wield. “We need sustainability-linked bonds with tie-ins to specific KPIs [key performance indicators] and penalties for missing them,” says Hickey. “If those are big enough to be meaningful for the company, that’s how we fund the transition.”

No comments:

Post a Comment