Chiara Albanese

Wed, September 28, 2022 at 9:00 PM·3 min read

(Bloomberg) -- Soon after Giorgia Meloni’s landslide win in Italy’s election, members of the Rainbow Families association of same-sex parents joined a heated email chain about the potential impact of the incoming right-wing government.

The subject line read: “Now what?”

Meloni has signaled to voters and investors that she will govern as a moderate. But the 45-year-old leader of the far-right Brothers of Italy party opposes abortion and believes family is comprised by the union of a man and a woman, and LGBTQ people are far from reassured.

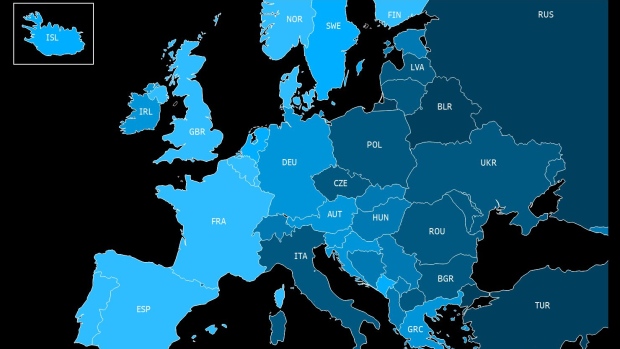

Already, Italy lags behind much of Europe in protecting their rights, placing near the bottom of one recent ranking — along with countries like Hungary and Poland which have cracked down their LGBTQ communities.

That’s largely because successive Italian governments have failed to introduce hate crime laws that cover sexual orientation and gender identity, and to recognize same-sex parents as families.

Marriage equality legislation has stalled in Italy, despite chiding from the European Union. So while same-sex couples have been able to enter a civil partnership since 2016, they still are not allowed to marry, meaning there is no automatic co-parent recognition.

These families are cut off from social benefits, help with school costs, paid parental leave and other state aid.

Same-sex parents seeking joint adoptions and legal recognition for their children must go to court (a lengthy and costly process which has become common in Italy) even though the Constitutional Court has urged parliament to legislate on the matter.

Meloni says she has no plans to overturn the civil union law, but has no interest in improving the legal situation for LGBTQ people, either. “You already have civil partnerships, what else would you ever want?” she said during a campaign rally after an activist jumped on stage to plead for more rights.

Earlier, in June, Meloni warned against the power of what she called the “LGBTQ lobby.”

There are some other dark clouds on the horizon.

Brothers of Italy backs a legal proposal to label surrogacy a universal crime. And in September, Federico Mollicone, who oversees cultural affairs for the party, pushed the state broadcaster not to air an episode of children’s tv show Peppa Pig featuring a family with two mothers. He claimed that Italy bans same-sex unions.

“We are about to face an even more challenging period for the LGBTQ community in Italy, which will face a lack of legal protection,” said Alexander Schuster, a university researcher and a lawyer member of Rainbow Families.

“We expect the elections to impact on the attitude of individual judges and of local administrators, which often place undue burdens upon gay parents,” Schuster said. “The shift towards a conservative attitude had already started, for instance at the Supreme Court, but could get worse.”

It’s difficult to know exactly how many families are affected as data is scarce and Italy’s last official census dates back about 10 years.

“The ideology is very clear, and against our families,” says Andrea Rubera, a father of three with his husband Dario De Gregorio. “It will be harder to talk about diversity, inclusion and different kind of families in schools. That leaves me embarrassed, and without an answer when I am asked by my daughter why for the state we are not a family.”

The hope for parents on the email chain is that Meloni means it when she says she will be a moderate prime minister. But even if she is, without progress, Italy won’t feel like a safe country for them.

The Sad Truth About How Italian Politics Are Holding Up LGBTQ Rights

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- For Giada Buldrini it wasn’t the one act of homophobia that turned her into a full-time activist. It came from being a girl never feeling safe to hold hands with another girl in public, to having to go overseas to be able to have children with another woman and to waking up at the age of 34 to death threats in her inbox for daring to be a lesbian and a mother.

“Until you read one, you can’t imagine what it’s like,” says the former postwoman from Rimini of the many menacing messages she’s received.

That this happened in a smugly liberal corner of Italy that was also one of the touchstones of the resistance to the Nazis, is a reminder of how far behind even core members of the European Union are on LGBTQ issues. Italy ranks lowest in western Europe for gender equality and a bill that criminalizes violence and hate speech targeting a person’s sexual orientation or identity has kicked off protests this weekend as to why, three years after it was first presented, something so basic is still so controversial. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Giada_Buldrini (@duemammetrefigli)

The law is in parliamentary limbo, with conservative senators arguing it would limit free speech and damage traditional Roman Catholic family values. In the meantime, Spain has overhauled its constitution to accept same-sex marriage while Poland moved the opposite way, creating LGBTQ-free zones. Italy is stuck in a frustrating middle, unwilling to embrace root-and-branch change yet shocked by the culture wars in Eastern Europe that are not so far removed from its own existential struggles.

“Italy needs to understand where it stands: it’s either with the EU, where civil rights are also part of a positive business environment, or with Poland and Hungary,” says Alessandro Zan, the 47-year-old openly gay Democratic Party lawmaker who introduced the bill, in an interview in Rome.

Calls for its passage have been growing since a horrific assault in March when a gay couple was beaten after kissing in a metro station in Rome. A video of the incident shows the mens’ attacker running across the train tracks toward them before repeatedly punching and kicking them, while shouting “are you not ashamed of yourselves?” The footage drew outrage after it was broadcast on local television, but usually such incidents garner less attention, and they’re not recorded in any official data as hate crimes.

Zan has achieved quasi-rockstar status in Italy. He recently staged a one-hour Instagram Live with Fedez, a popular rapper who supports the law and has 12 million followers. And during a demonstration in Milan, he walked alongside Francesca Pascale, the ex-fiancee of Silvio Berlusconi who drew tasteless headlines for dating women.

Whether you love him or hate him comes down to which side of the ideological divide you fall on. By and large, the center-left back him while the center-right won’t. And yet, there are signs of a shift in the status quo. Alessandra Mussolini, the right-wing granddaughter of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, endorsed him by posting an Instagram selfie with ‘Zan’ written on her palm. View this post on Instagram A post shared by Alessandra Mussolini (@alemussolini_)

A complicating factor is the Catholic Church based in Rome.

Pope Francis was heralded as the best hope for liberals, but in all of this the Vatican has repeated that it cannot bless same-sex unions and has come out against the Zan law. That’s given Matteo Salvini’s League, the most popular party in the country, yet more reason to hold steadfast in its opposition. Mario Draghi, the current prime minister, is unelected and with a strict mandate to fix the post-pandemic economy before stepping aside after a year or two from now when Italians will go to the ballots.

Salvini has been a vocal opponent of LGBTQ rights, denying the children of same-sex unions to have the name of both parents on national ID cards when he served as interior minister. Andrea Ostellari, the League senator who heads the justice commission that oversees the approval process for social rights bills, has yet to even schedule a debate. He says the issue is too divisive and not as pressing as say, animal rights.

Even if a debate were to start immediately, the bill’s passage could take months.

The electorate meanwhile is more divided than one would think, with about 68% of Italians saying that gay, lesbian or bisexual people should have the same legal rights compared to heterosexuals, compared to 98% in Sweden, 88% in Germany and 85% in France, according to a European Commission survey from 2019.

There is ambivalence to the Zan law even among the community it wants to protect. Put simply, some just don’t think it goes far enough and are tired of settling for less.

Though Italy approved same-sex civil unions in 2016, it still denies same sex couples the right to both register as parents of their children — and in the absence of a national law on the matter each city interprets existing legislation differently, creating confusion damaging to both parents and children. For example, two women married in the EU who decide to have a child in Turin or Palermo may be able to both officially register as parents of the baby, whereas in Rome only the woman giving birth will be considered the mother.

And just outside the capital, near the airport of Fiumicino, city hall was allowing registrations until judges in nearby Civitavecchia questioned the practice, leading to panic and hefty legal costs for the families who’d already signed up. Italy’s Constitutional Court said “the continued legislative inertia is no longer tolerable.”

“Much more needs to be done and quickly, in particular for children,” says Monica Cirinnà, the Democratic Party lawmaker who battled for the civil union law yet freely admits that it was hopelessly flawed.

There are things that don’t just affect the LGBTQ community. If you’re a single heterosexual woman who wants to have a child on her own, artificial insemination is out of the question unless you have the means to pursue it outside of Italy. Buldrini and her partner wound up travelling to Spain to conceive. After their return, and even after the birth of their twins, they still chose not to enter into a civil partnership.

“For a family,” says Buldrini, “it adds duties without rights.”

No comments:

Post a Comment