COP15

Conservationists optimistic over David Eby's commitments to protect B.C.'s biodiversity

Land stewardship mandate letter calls for 30 per cent of

B.C.’s land base to be protected by 2030

In mandate letters to his land stewardship and forestry ministers, B.C. Premier David Eby says he wants to double the amount of protected land in the province, support new Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, and move faster on recommendations around the logging of old growth trees.

They're conservation goals advocates have been calling on for years to protect B.C.'s unique biodiversity, which has thousands of species at risk due to development and climate change.

"This is potentially a major leap toward protecting endangered ecosystems and the most at-risk, productive stands of old-growth forests left in B.C.," said Ken Wu in a release from the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance.

Experts say protected areas help mitigate the worst effects of climate change, contribute to diversifying local economies and advance reconciliation with First Nations.

This week, Eby named his first cabinet as premier, with former energy and mines minister Bruce Ralston taking on forestry and Nathan Cullen replacing Josie Osborne as the minister for water, land and resource stewardship. The new ministry was put in place in February.

The tone of the letters appears to usher in the type of science-based, holistic approach to conservation and biodiversity in the province that people like Wu have been asking for from the B.C. government.

"We have seen the impacts of short-term thinking on the British Columbia land base — exhausted forests, poisoned water, and contaminated sites," wrote Eby is his mandate letter to Cullen.

"These impacts don't just cost the public money to clean up and rehabilitate, they threaten the ability of entire communities to thrive and succeed."

The highlight is finding ways to partner with the federal government, First Nations, industry and communities to protect 30 per cent of B.C.'s landbase by 2030, including Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs).

IPCAs are lands and waters where Indigenous governments have the primary role in protecting and conserving ecosystems through Indigenous laws, governance and knowledge.

"Research shows that biodiversity thrives on Indigenous-managed lands and waters," said Tori Ball with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, British Columbia.

Canada is committed to protecting 25 per cent of lands and 25 per cent of oceans by 2025,and 30 per cent of each by 2030.

Currently protected lands cover around 15 per cent of B.C.'s land base. Critics say ecological zones with the highest biodiversity are underrepresented.

Old growth

Both letters also ask for the ministers to implement 14 recommendations made more than two years ago in a review of how old growth trees are logged in B.C., specifically transitioning to an industry that prioritizes the health of ecosystems.

Critics say the government has so far moved too slowly on action items as old growth trees in ecologically-rich areas continue to be logged.

Cullen's mandate letter also calls for the development of a "new conservation financing mechanism to support protection of biodiverse areas," but does not expand on what that might be or how it would work.

B.C. has yet to announce matching funding from the federal government, which ear-marked $55.1 million over three years to establish a B.C. "Old Growth Nature Fund" in its budget earlier this year.

The Sierra Club of B.C. said that reaching the commitments in the letters will depend on immediacy, proper funding, and transparency over timelines and milestones.

"Without immediate change on the ground the window of action to safeguard biodiversity as we know it is rapidly closing," said Jens Wieting with Sierra Club B.C.

B.C. vows to reverse ‘short-term thinking’

with pledge to protect 30% of province by

2030

Advocates say Premier David Eby’s conservation mandate is an ‘important step’ in the fight against biodiversity loss in B.C., which is home to nearly 700 globally imperilled species

Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Dec. 8, 2022

The B.C. government has committed to protecting 30 per cent of the province’s land by 2030, joining global efforts to protect nature and reverse potentially disastrous biodiversity loss.

The commitment to double B.C.’s current land protections was made in Premier David Eby’s mandate letter to Nathan Cullen, B.C.’s new Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. Eby instructed Cullen to ensure land operations in the province guarantee sustainability for future generations and to work closely with Indigenous communities to achieve that goal.

“We have seen the impacts of short-term thinking on the British Columbia land base — exhausted forests, poisoned water and contaminated sites,” Eby’s letter states. “These impacts don’t just cost the public money to clean up and rehabilitate, they threaten the ability of entire communities to thrive and succeed.”

The letter instructs Cullen to partner with the federal government, industry and communities, and to work with Indigenous communities to reach the 2030 protection goal, including through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) are gaining recognition worldwide for their role in preserving biodiversity and securing a space where communities can actively practice Indigenous ways of life.

“By planning carefully, we can ensure our province enjoys the best of economic development while conserving wild spaces,” Eby writes. “Indigenous partners in this critical work can bring their expertise, knowledge and priorities to the table to ensure this effort lasts for generations.”

B.C. is poised to announce a long-awaited nature agreement with the federal government that will include a commitment to new protected areas and, according to internal documents obtained by The Narwhal, new protections for “high profile” species such as boreal caribou and spotted owls. The agreement is referenced in Cullen’s mandate letter, but no details are provided other than that it includes the goal to protect 30 per cent of the province by 2030.

About 15 per cent of B.C.’s land is currently conserved in provincial and federal protected areas.

All members of B.C.’s new cabinet received mandate letters Dec. 7 following a cabinet shuffle that saw Cullen’s predecessor Josie Osborne moved to the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation.

In Cullen’s letter, Eby also asks the MLA for Stikine to work with other ministries to develop a “new conservation financing mechanism to support protection of biodiverse areas.”

Conservation groups were quick to applaud the commitments — made as delegates from around the world gather in Montreal for COP15, the United Nations biodiversity conference — calling the news “very encouraging,” “fantastic” and “worthy of international and national attention.”

“It’s great to see provinces like B.C. and Quebec recognizing that the environment and protecting nature is critical, not just for nature, but for the well-being of people and the prosperity of our society,” Dan Kraus, director of national conservation for Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, told The Narwhal, referring to a recent commitment by the Quebec government to protect 30 per cent of its territory by 2030.

Ken Wu, executive director of the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, said B.C. should be commended for committing to federal targets for protecting nature and biodiversity.

“It’s more than what most provinces have done,” Wu said in an interview. “With the exception of Quebec, most provinces have been conservation laggards both in terms of target and in terms of providing funding. So this is an important step.”

Gillian Staveley, director of land stewardship and culture with the Dena Kayeh Institute, said she is pleased the B.C. government is “finally” talking about Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. She praised the “cross-government approach” and called the minister’s letter a “strong mandate.”

“We look forward to rolling up our sleeves and meeting with Minister Cullen as soon as possible to get discussion underway in the work with B.C. to really make our proposed IPCA a reality for the benefit of all British Columbians,” Staveley texted as she boarded a flight to Montreal to attend COP15.

The Kaska Dena aim to protect a wildlife-rich area in their territory, known as the “Serengeti of the North,” through a proposed Indigenous protected area that would conserve a 40,000 square-kilometre region.

The Kaska protected area in northern B.C. would surround or connect to six existing protected areas, conserving watersheds and critical habitat for caribou and other species at risk of extinction while creating sustainable jobs. Staveley noted that Cullen has always been supportive of Dene K’eh Kusān, which in Kaska Dena means “always will be there.”

“Having 30 by 30 as a policy priority is also a big step towards the action we need,” Staveley said. “It leaves us hopeful that Premier Eby intends to be an activist premier and he understands the urgency to getting these protections in place to address climate change and loss of biodiversity.”

B.C. called the ‘biodiversity jewel’ of Canada

Wu and Kraus said they will be watching closely to see which areas of B.C. are protected, noting it’s of paramount importance to conserve areas at the highest risk of biodiversity loss.

Kraus called B.C. the “biodiversity jewel” of Canada. The province has almost 700 globally imperilled species, more than any other province or territory, and a high number of globally threatened ecosystems — 88 at last count, but Kraus noted that ecosystems are not tracked nearly as well as individual species. B.C. also ranks number one in Canada for endemic species, which top 100. Endemic species do not occur naturally in any other part of the world.

“What happens in B.C. is critical for meeting both national and global biodiversity targets,” Kraus said.

Places with high numbers of threatened species and globally imperilled ecosystems include the Lower Mainland and Okanagan area in B.C.’s interior, as well as the provincial capital area of Victoria where almost nothing remains of the now-rare Garry Oak ecosystem that once carpeted the region.

Northern spotted owls, which in Canada live only in old-growth forests in southwest B.C., are critically endangered. Photo: Province of British Columbia / Flickr

Northern spotted owls, which in Canada live only in old-growth forests in southwest B.C., are critically endangered. Photo: Province of British Columbia / Flickr

“We do know where those places are,” Kraus said. “And that focus on biodiversity areas allows us to protect habitat that will [conserve] a whole bunch of species at risk — globally imperiled species [and] nationally imperiled species that aren’t yet listed under the Species At Risk Act … we can be proactive in conserving them by protecting those habitat areas.”

Eby’s letter also instructs Cullen to “protect wildlife and species at risk.” It makes no mention of enacting a stand-alone law to protect B.C.’s growing number of species and ecosystems at risk of extinction, as promised in the 2017 mandate letter for B.C. Minister of Environment and Climate Change George Heyman — but then quietly dropped by the B.C. NDP government.

Instead, Cullen is asked to protect and enhance B.C.’s biodiversity by implementing the recommendations of an old-growth strategic review panel and a somewhat vague, previously announced strategy called Together for Wildlife.

Wu said Eby’s commitment to create a new conservation financing mechanism “may just be words” but the words signify the province is on the right path to establish economic development funding for First Nations tied to protecting places at the greatest risk of biodiversity loss.

“If they follow through with that, without spin, then that is a monumental leap forward,” he said, cautioning that the province has undertaken “creative accounting” in the past regarding how it counts protected areas. Designations such as old-growth management areas, ungulate winter range and wildlife habitat areas lack permanence or the standards of legally protected areas, Wu pointed out.

“Some of these conservation regulations are sort of like the cryptocurrency of protected areas,” he said.

New initiatives could end B.C.’s ‘war in the woods’

Other key elements of Cullen’s mandate include working with First Nations to “improve the protection and stewardship of forest resources, habitats, biodiversity and cultural heritage in the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement” and to “work toward modern land use plans and permitting processes rooted in science and Indigenous knowledge that consider new and cumulative impacts to the land base.”

Cullen was also instructed to work with the Ministry of Forests to begin implementation of recommendations made by an old-growth strategic review panel, which called for a paradigm shift in the way B.C. manages its forests and immediate deferrals from logging for old-growth forests at the highest risk of biodiversity loss.

In a 2019 United Nations report, scientists warned global biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate, with about one million species facing extinction. They also said there is still time to turn things around with transformative change.

At the biodiversity conference underway in Montreal, close to 200 countries are working to finalize an agreement to reverse biodiversity loss and avoid devastating outcomes from the sixth mass extinction event in the Earth’s history, caused by human activity.

The global agreement aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 and achieve its full recovery by 2050.

Wu said B.C. must develop protection targets for all ecosystems and prioritize protection for the most endangered and least represented ecosystems. Economic development funding for First Nations should be tied to the protection of the most at-risk most productive old-growth forests, he said. Old-growth forests with the highest productivity — the biggest trees and the most species at risk of extinction — are found in valley bottoms.

Wu said the province will “get the job done” with a land acquisition fund that can also be used to buy private lands with endangered ecosystems.

“If they protect the valley bottoms, southern parts of the province, lower elevations most at risk, [and] old-growth forests and ecosystems, then they could put an end to the 50-year-old war in the woods.”

The Canadian Press

Published Dec. 9, 2022

OTTAWA -

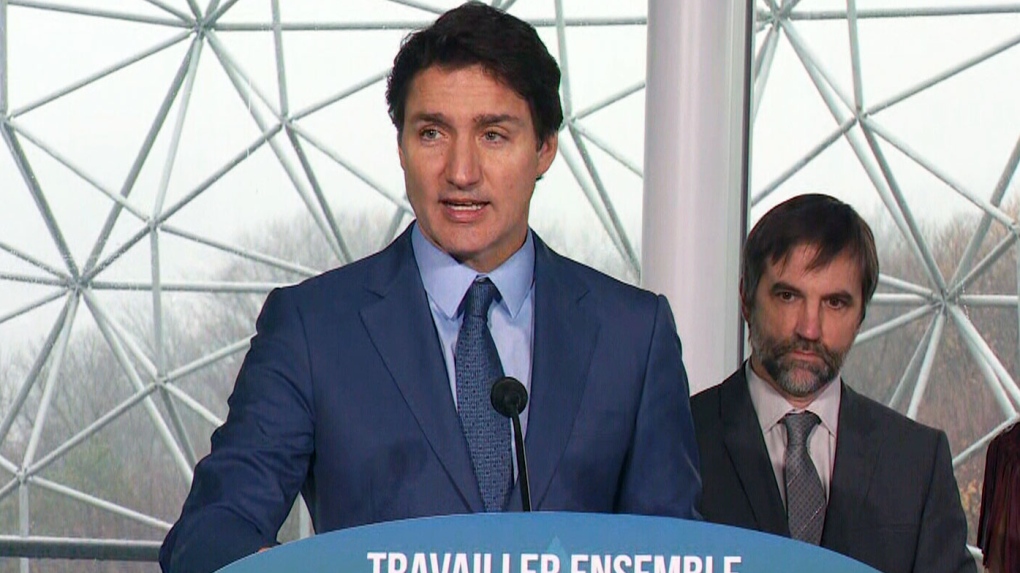

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was unequivocal Wednesday when asked if Canada was going to meet its goal to protect one-quarter of all Canadian land and oceans by 2025.

"I am happy to say that we are going to meet our '25 by 25' target," Trudeau said during a small roundtable interview with journalists on the sidelines of the nature talks taking place in Montreal.

That goal, which would already mean protecting 1.2 million more square kilometres of land, is just the interim stop on the way to conserving 30 per cent by 2030 -- the marquee target Canada is pushing for during the COP15 biodiversity conference.

But what does the conservation of land or waterways actually mean?

"When we talk about protecting land and water, we're talking about looking at a whole package of actions across broader landscapes," said Carole Saint-Laurent, head of forest and lands at the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The group's definition of "protected area," which is used by the UN convention on biodiversity, refers to a "clearly defined geographical space" that is managed by laws or regulations with the goal of the long-term protection of nature.

"It can range from areas with very strict protections to areas that are being protected or conserved," said Saint-Laurent.

"We have to look at that entire suite of protective and restorative action in order to not only save nature, but to do so in a way that is going to help our societies. There is not one magical formula, and context is everything."

The organization, which keeps its own global "green list" of conserved areas, lists 17 criteria for how areas can fit the definition.

Most of the criteria are centred on how the sites are managed and protected. One allows for resource extraction, hunting, recreation and tourism as long as these are both compatible with and supportive of the conservation goals outlined for the area.

In many cases, industrial activities and resource extraction are not allowed in protected areas. But that's not always true in Canada, particularly when it involves the rights of Indigenous Peoples on their traditional territory.

In some provincial parks, mining and logging are allowed. In Ontario's Algonquin Park, for example, logging is permitted in about two-thirds of the park area.

Canada has nearly 10 million square kilometres of terrestrial land, including inland freshwater lakes and rivers, and about 5.8 million square kilometres of marine territory.

As of December 2021, Canada had conserved 13.5 per cent of land and almost 14 per cent of marine territory. The government did it through a combination of national and provincial parks and reserves, wildlife areas, migratory bird sanctuaries, national marine conservation areas, marine protected areas and what are referred to as "other effective areas-based conservation measures."

These can include private lands that have a management plan to protect and conserve habitats, or public or private lands where conservation isn't the primary focus but still ends up happening.

Canadian Forces Base Shilo, in Manitoba, includes about 211 square kilometres of natural habitats maintained under an environmental protection plan run by the Department of National Defence.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada is a non-profit organization that raises funds to buy plots of land from private owners with a view to long-term conservation.

Mike Hendren, its Ontario regional vice-president, said that on such lands, management plans can include everything from nature trails to hunting -- but always with conservation as the priority.

To hit "25 by 25," Canada must further protect more than 1.2 million square kilometres of land, or approximately the size of Manitoba and Saskatchewan added together. To get to 30 per cent is to add, on top of that, land almost equivalent in size to Alberta.

The federal government would need to protect another 638,000 square kilometres of marine territory and coastlines by 2025, or an area almost three times the size of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. By 2030, another area the size of the gulf would need to be added.

Trudeau said that in a country as big and diverse as Canada, hard and fast rules about what can and can't happen in protected areas don't make sense.

He said there should be distinctions between areas that can't have any activity and places where you can mine, log or hunt, as long as it is done with conservation in mind.

"There's ability to have sort of management plans that are informed by everyone, informed by science, informed by various communities, that say, 'yes, we're going to protect this area and that means, no, there's not going to be unlimited irresponsible mining going to happen,"' he said.

"But it doesn't mean that there aren't certain projects in certain places that could be the right kind of thing, or the right thing to move forward on."

The draft text of the biodiversity framework being negotiated at COP15 is not yet clear on what kind of land and marine areas would qualify or what conservation of them would specifically mean.

It currently proposes that a substantial portion of the conserved land would need to be "strictly protected" but some areas could respect the right to economic development.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivers remarks during the opening ceremony of the COP15 UN conference on biodiversity in Montreal, Tuesday, Dec. 6, 2022. Trudeau was unequivocal Wednesday when asked if Canada was going to meet its goal to protect one-quarter of all Canadian land and oceans by 2025. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson)

'Paris moment': COP15 conference in Montreal seeks hard targets on biodiversity

Major biodiversity conference opens in Montreal amid hope of hard conservation target

Financial institutions have a role to play in preserving biodiversity: COP negotiator

Trudeau says 120 countries are ready to agree to '30 by 30' framework at COP15

Hard talks on hard targets: real work begins at Montreal biodiversity conference Climate Barometer newsletter: Sign up to keep your finger on the climate pulse

No comments:

Post a Comment