An 11-year study found women using chemical straighteners had double the risk of uterine cancer faced by those who didn’t use the products.

Photograph: Vystekimages/Getty Images/Photononstop RF

Studies show the products may double the risk of uterine cancer, but tradition, societal pressure and personal taste create obstacles to change

Deborah Douglas

Studies show the products may double the risk of uterine cancer, but tradition, societal pressure and personal taste create obstacles to change

Deborah Douglas

THE GUARDIAN

Mon 12 Dec 2022

Jeanet Stephenson stacks two boxes of hair relaxer on her bathroom sink. She shakes out her long hair before leaning down to reveal wavy roots at her middle part to the camera – straightening this patch of her hair is the purpose of her TikTok video Come Get a Relaxer With Me, Pt 2. A remix of SZA plays in the background as she slicks her hair down with the white chemical concoction from one of the boxes. By the end of the demo clip she is smiling into the camera, glossy-lipped, with an air of satisfaction and shiny, straight, blown-out tresses falling past her shoulders.

The 22-year-old nursing student in Montgomery, Alabama, occasionally gets pushback for posting videos of chemically straightening her hair. Commenters will respond, “Relaxers are damaging, so I don’t see how it’s healthy at all,” or “It’s literally chemicals that make ur hair permanently straight. It doesn’t matter how professionally you do it, it’s still damaging.”

Jeanet Stephenson stacks two boxes of hair relaxer on her bathroom sink. She shakes out her long hair before leaning down to reveal wavy roots at her middle part to the camera – straightening this patch of her hair is the purpose of her TikTok video Come Get a Relaxer With Me, Pt 2. A remix of SZA plays in the background as she slicks her hair down with the white chemical concoction from one of the boxes. By the end of the demo clip she is smiling into the camera, glossy-lipped, with an air of satisfaction and shiny, straight, blown-out tresses falling past her shoulders.

The 22-year-old nursing student in Montgomery, Alabama, occasionally gets pushback for posting videos of chemically straightening her hair. Commenters will respond, “Relaxers are damaging, so I don’t see how it’s healthy at all,” or “It’s literally chemicals that make ur hair permanently straight. It doesn’t matter how professionally you do it, it’s still damaging.”

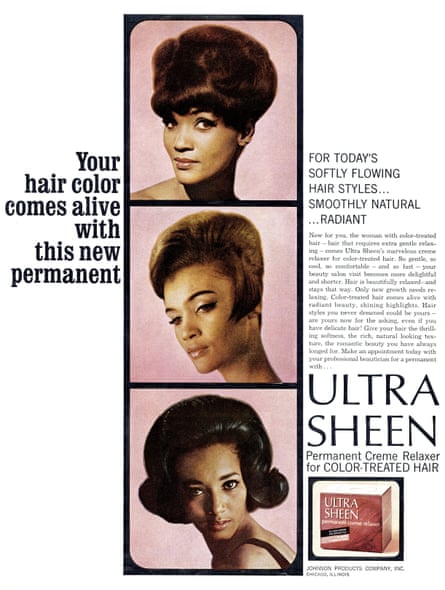

Now more than ever before, the risks of wearing relaxers has been clearly laid out.

Photograph: PermaStrate

But for Stephenson, “a lot of stuff in the world isn’t safe”. She says her tresses are healthy and more manageable, and refuses to give relaxers up.

Whether it’s personal preference, tradition, or response to external pressure to have straight hair, relaxers are a habit many Black women just won’t, or can’t, quit. Michelle Obama recently spoke to the pressure to conform to a certain aesthetic while serving as first lady. During an appearance in Washington DC to promote her new book she said, wearing long braids on stage: “As Black women, we deal with it, the whole thing about do you show up with your natural hair? As first lady, I did not wear braids. I thought about it … nope, nope, they’re not ready.”

The problem is that now more than ever, the risks of wearing relaxers has been clearly laid out. In groundbreaking research released in October, a National Institutes of Health study of about 34,000 women ages 35-74 conducted over almost 11 years found the women who reported using chemical straighteners had double the risk of uterine cancer faced by women who didn’t use these products.

Frequent use of hair-straightening products may raise uterine cancer risk, study says

“Because Black women use hair-straightening or relaxer products more frequently and tend to initiate use at earlier ages than other races and ethnicities, these findings may be even more relevant for them,” Dr Che-Jung Chang, a co-author of the study, said in a statement.

Just days after the study was released, a 32-year-old Black woman from Missouri, Jenny Mitchell, filed a lawsuit against L’Oréal, Strength of Nature, SoftSheen Carson, Dabur International, and Namaste Laboratories – all makers of chemical straighteners and hair relaxers. She got her first relaxer around age eight, amid social norms about having “sleek, nice, laid hair”, Mitchell said. Now, as a uterine cancer survivor who has undergone a hysterectomy and premature menopause, Mitchell cites relaxers as the reason she will never be able to bear children.

Mitchell learned about her cancer while seeking fertility treatments to fulfill her dream of becoming a mother. “That’s always something that I wanted,” says Mitchell, who has 14 nieces and nephews. “I always wanted my great-aunt to see my kids, see my child. It was a dream that I’ve always had that was just snatched away from me.”

Over the past decade, chemical relaxer sales to hair professionals and salons declined, from $71m in 2011 to $30m in 2021, according to the market research firm the Kline Group; Mitchell is one of many Black women who have foregone relaxers and she wears her hair naturally, cut closely to her head.

The defendants have not yet filed an answer to the lawsuit, according to Mitchell’s attorney, Diandra “Fu” Debrosse Zimmermann. Mitchell’s legal team said they expected many more women to file additional lawsuits against the defendants and would ask for all of them to be handled under one federal judge.

“If Jenny prevails, it will be no less significant than the first case where we discovered that smoking caused cancer and that there had to be repercussions,” says Noliwe Rooks, chair of Africana studies at Brown University, who weaves the story of hair into courses she teaches about Black women because it is a crucial element of the Black experience in America. And, if Mitchell prevails, Black women could be faced with a different kind of conversation about hair and adornment – that of adverse and unequal health consequences.

But for Stephenson, “a lot of stuff in the world isn’t safe”. She says her tresses are healthy and more manageable, and refuses to give relaxers up.

Whether it’s personal preference, tradition, or response to external pressure to have straight hair, relaxers are a habit many Black women just won’t, or can’t, quit. Michelle Obama recently spoke to the pressure to conform to a certain aesthetic while serving as first lady. During an appearance in Washington DC to promote her new book she said, wearing long braids on stage: “As Black women, we deal with it, the whole thing about do you show up with your natural hair? As first lady, I did not wear braids. I thought about it … nope, nope, they’re not ready.”

The problem is that now more than ever, the risks of wearing relaxers has been clearly laid out. In groundbreaking research released in October, a National Institutes of Health study of about 34,000 women ages 35-74 conducted over almost 11 years found the women who reported using chemical straighteners had double the risk of uterine cancer faced by women who didn’t use these products.

Frequent use of hair-straightening products may raise uterine cancer risk, study says

“Because Black women use hair-straightening or relaxer products more frequently and tend to initiate use at earlier ages than other races and ethnicities, these findings may be even more relevant for them,” Dr Che-Jung Chang, a co-author of the study, said in a statement.

Just days after the study was released, a 32-year-old Black woman from Missouri, Jenny Mitchell, filed a lawsuit against L’Oréal, Strength of Nature, SoftSheen Carson, Dabur International, and Namaste Laboratories – all makers of chemical straighteners and hair relaxers. She got her first relaxer around age eight, amid social norms about having “sleek, nice, laid hair”, Mitchell said. Now, as a uterine cancer survivor who has undergone a hysterectomy and premature menopause, Mitchell cites relaxers as the reason she will never be able to bear children.

Mitchell learned about her cancer while seeking fertility treatments to fulfill her dream of becoming a mother. “That’s always something that I wanted,” says Mitchell, who has 14 nieces and nephews. “I always wanted my great-aunt to see my kids, see my child. It was a dream that I’ve always had that was just snatched away from me.”

Over the past decade, chemical relaxer sales to hair professionals and salons declined, from $71m in 2011 to $30m in 2021, according to the market research firm the Kline Group; Mitchell is one of many Black women who have foregone relaxers and she wears her hair naturally, cut closely to her head.

The defendants have not yet filed an answer to the lawsuit, according to Mitchell’s attorney, Diandra “Fu” Debrosse Zimmermann. Mitchell’s legal team said they expected many more women to file additional lawsuits against the defendants and would ask for all of them to be handled under one federal judge.

“If Jenny prevails, it will be no less significant than the first case where we discovered that smoking caused cancer and that there had to be repercussions,” says Noliwe Rooks, chair of Africana studies at Brown University, who weaves the story of hair into courses she teaches about Black women because it is a crucial element of the Black experience in America. And, if Mitchell prevails, Black women could be faced with a different kind of conversation about hair and adornment – that of adverse and unequal health consequences.

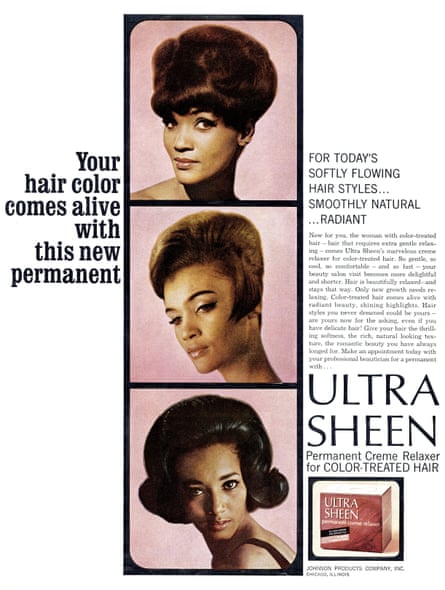

An advertisement for hair relaxer from 1966. Photograph: Granger/Shutterstock

In addition to the October study, a 2021 Oxford University Carcinogenesis Journal study found that frequent, long-term use of lye-based relaxers could have serious health effects, including breast cancer. And Dr Tamarra James-Todd at Harvard University’s Chan School of Public Health has found hormone-disrupting chemicals in half of hair products marketed to Black women, compared with 7% for white women.

“Estrogen levels are involved in breast cancer, for example, and ovarian cancer, as well as uterine cancer,” James-Todd says. “I don’t want anything that’s sitting on the shelf of a store to up-regulate or down-regulate my hormone levels.”

Weighing the risks of using these products has largely been left to consumers because relaxers and hair straighteners are considered cosmetic products, the US Food and Drug Administration said in an emailed statement. “Cosmetic products and ingredients, other than color additives, do not need FDA approval before they go on the market,” according to an agency spokesperson. If a product has been adulterated or misbranded, consumers can report it to the FDA.

Tatiana Smith, a 29-year-old New Jersey-based accountant and bodybuilder, works out almost daily. She tried natural hairstyles for a year, but sweating at the gym and damp weather made for less-than ideal results. “I go out one way from home, and get to the office and I looked different,” she says. “I always know what I’m getting with a relaxer.” She adds: “We know there is a chance for all types of things, cancer included, but I think we’ve heard it before. You really can pick your poison in this country.”

As much as Smith’s decision is personal, what Black women choose to do with their hair has always lived in tension with self- and cultural expression, and the quest for inclusion in American society.

Relaxers, or perms (as they are sometimes called in the Black community because they are meant to be semi-permanent), became a staple in the 1940s, when top Black entertainers sported sleek, processed waves, suggesting sophistication as well as belonging. Before then, all kinds of products purported to straighten Black hair, but it wasn’t until the 40s that women could begin to trust over-the-counter formulations “a little bit”, according to Rooks.

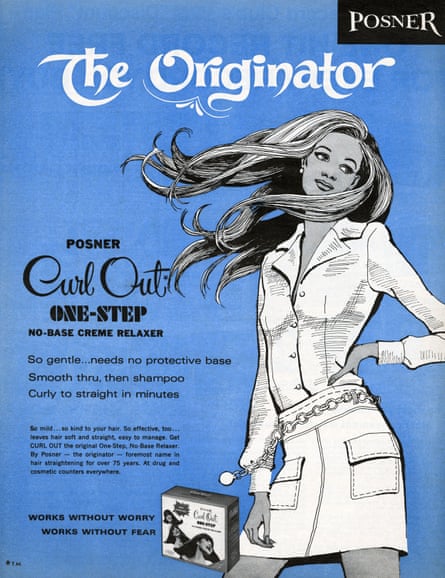

In the 60s, young people embraced Black pride and began wearing naturals, “which was all kinds of horrifying for people”, Rooks says, referring to a lack of acceptance of short afros both from segments of the older Black generation and from various races in professional settings. During this era, relaxers largely went out of style.

“Beauty companies come along and say, ‘Well, let’s kind of split the difference. You don’t necessarily have to have hair that is speaking to Black pride as much as an aesthetic of an afro, but that’s looser and wavy,’” Rooks says. “And those blowout kits actually sort of revived the sale of relaxers, [which] had taken a little bit of a dip in the heart of the Black Power period.” Next came Jheri curls in the 80s, followed by weaves, says Rooks, noting that in the 90s, stories about Black women being fired for wearing natural hairstyles were emerging. The 2000s ushered in a generational change as young people prioritized versatility, she says, so if they wanted to wear straight hair one day and a pink wig or locs the next, everything was fair game.

But with more discussion of self-care as well as self-acceptance in the last decade or so, use of relaxers has dipped significantly. “To a certain extent, you have in the last 10 years started to have more conversations about hair relaxers and health, so you hear about alopecia perhaps having something to do with relaxers,” says Rooks, who sports an above-the-shoulder twist-out style for her salt-and-pepper hair.

As the modern natural hair movement took off, however, Rooks began noticing Black women talking about undergoing “the big chop” to get rid of relaxed hair and make room for new, naturally curly hair to take its place, using words like “self-care” and moving towards self-acceptance.

In addition to the October study, a 2021 Oxford University Carcinogenesis Journal study found that frequent, long-term use of lye-based relaxers could have serious health effects, including breast cancer. And Dr Tamarra James-Todd at Harvard University’s Chan School of Public Health has found hormone-disrupting chemicals in half of hair products marketed to Black women, compared with 7% for white women.

“Estrogen levels are involved in breast cancer, for example, and ovarian cancer, as well as uterine cancer,” James-Todd says. “I don’t want anything that’s sitting on the shelf of a store to up-regulate or down-regulate my hormone levels.”

Weighing the risks of using these products has largely been left to consumers because relaxers and hair straighteners are considered cosmetic products, the US Food and Drug Administration said in an emailed statement. “Cosmetic products and ingredients, other than color additives, do not need FDA approval before they go on the market,” according to an agency spokesperson. If a product has been adulterated or misbranded, consumers can report it to the FDA.

Tatiana Smith, a 29-year-old New Jersey-based accountant and bodybuilder, works out almost daily. She tried natural hairstyles for a year, but sweating at the gym and damp weather made for less-than ideal results. “I go out one way from home, and get to the office and I looked different,” she says. “I always know what I’m getting with a relaxer.” She adds: “We know there is a chance for all types of things, cancer included, but I think we’ve heard it before. You really can pick your poison in this country.”

As much as Smith’s decision is personal, what Black women choose to do with their hair has always lived in tension with self- and cultural expression, and the quest for inclusion in American society.

Relaxers, or perms (as they are sometimes called in the Black community because they are meant to be semi-permanent), became a staple in the 1940s, when top Black entertainers sported sleek, processed waves, suggesting sophistication as well as belonging. Before then, all kinds of products purported to straighten Black hair, but it wasn’t until the 40s that women could begin to trust over-the-counter formulations “a little bit”, according to Rooks.

In the 60s, young people embraced Black pride and began wearing naturals, “which was all kinds of horrifying for people”, Rooks says, referring to a lack of acceptance of short afros both from segments of the older Black generation and from various races in professional settings. During this era, relaxers largely went out of style.

“Beauty companies come along and say, ‘Well, let’s kind of split the difference. You don’t necessarily have to have hair that is speaking to Black pride as much as an aesthetic of an afro, but that’s looser and wavy,’” Rooks says. “And those blowout kits actually sort of revived the sale of relaxers, [which] had taken a little bit of a dip in the heart of the Black Power period.” Next came Jheri curls in the 80s, followed by weaves, says Rooks, noting that in the 90s, stories about Black women being fired for wearing natural hairstyles were emerging. The 2000s ushered in a generational change as young people prioritized versatility, she says, so if they wanted to wear straight hair one day and a pink wig or locs the next, everything was fair game.

But with more discussion of self-care as well as self-acceptance in the last decade or so, use of relaxers has dipped significantly. “To a certain extent, you have in the last 10 years started to have more conversations about hair relaxers and health, so you hear about alopecia perhaps having something to do with relaxers,” says Rooks, who sports an above-the-shoulder twist-out style for her salt-and-pepper hair.

As the modern natural hair movement took off, however, Rooks began noticing Black women talking about undergoing “the big chop” to get rid of relaxed hair and make room for new, naturally curly hair to take its place, using words like “self-care” and moving towards self-acceptance.

A 1968 advertisement. In the 60s, relaxers largely went out of style.

Photograph: Granger/Shutterstock

Many had learned to “distrust and dislike” their natural hair from parents and grandparents, probably responding to generations of external pressure to conform. Then, she says, society reinforces internalized messages about acceptability, by suggesting, “We want you to look a certain kind of way if you’re going to work for our airline, for our hotels, if you’re going to make it into corporate boardrooms.” When Black women tease out what that certain kind of way is, Rooks says, “it’s not the hair like it looks, how it’s grown out your head”.

With more Black women having serious conversations about connections between haircare products and health conditions, Rooks can find “no murmurs of, no hints” of concern by the government or among companies about the safety of these formulations.

A lot of “girlfriend conversations” have involved rethinking the idea of putting formulations with lye, an ingredient used in plumbing, on their heads, though there are plenty of no-lye options on the market.

Black women have reconsidered scalp-level issues, such as relaxer burns, scabbing, and hair loss, says Rooks, who is among the featured guests on Hulu’s The Hair Tales, Tracee Ellis Ross’s recent exploration of Black women’s notions of beauty and identity. Other guests include Oprah Winfrey, Chloe Bailey and the Massachusetts congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, among others.

“We hear about fibroids having something to do with relaxers,” Rooks says of the benign pelvic tumors Black women are two to three times more likely to suffer than white women. Fibroids are also the main reason women get hysterectomies, according to the Black Women’s Health Imperative. “So that has put the brakes on it as well.”

But Black women will continue to wrestle with the pressure to use relaxers to feel socially accepted, according to Alice Gresham, a Philadelphia-based clinical director for outpatient mental health. The Hair Tales makes “it clear the kind of trauma that we’ve been experiencing around a physical attribute secondary to our skin, which of course is still trauma, and it’s double trauma or complicated trauma,” Gresham tells TikTok viewers in a video responding to the Hulu series.

She says in professional settings, including at their jobs, Black women are subject to both hypervisibility – being scrutinized about everything from the work they do to how they look when doing it – and invisibility in being rewarded for good work. This duality produces “a psychosis in Black women in the workplace” trying to fit into corporate structures with the “right” look.

Gresham says she is incensed it is taking so long to make a federal law out of the Crown Act, which would make discrimination based on a person’s texture or style of hair illegal. The bill was co-sponsored by the Democratic representatives Ilhan Omar and Pressley, two Black women, and passed the House but stalled in the Senate. The Democratic New Jersey senator Cory Booker is expected to reintroduce the bill in the next Congress.

“The message is basically, it might be OK for you to do something different with your hair or be natural with your hair,” according to Gresham, who says trauma sets in when non-Black people “say the most ridiculous ignorant things to you about it, including trying to touch it or making comments in front of other people, asking you ‘Is that real?’ or ‘Your hair is so interesting how you have it in a different way each and every day.’”

Gresham says she has mentored women who struggle with thinning and brittle hair after years of relaxer use when the social acceptance they have been chasing hasn’t worked out the way they thought it would. “I believe there’s a bit of an attachment there, like ‘decent’ is relaxing, making it straight,” Greshman says. “We’re still struggling with natural hair in its natural way.”

Many had learned to “distrust and dislike” their natural hair from parents and grandparents, probably responding to generations of external pressure to conform. Then, she says, society reinforces internalized messages about acceptability, by suggesting, “We want you to look a certain kind of way if you’re going to work for our airline, for our hotels, if you’re going to make it into corporate boardrooms.” When Black women tease out what that certain kind of way is, Rooks says, “it’s not the hair like it looks, how it’s grown out your head”.

With more Black women having serious conversations about connections between haircare products and health conditions, Rooks can find “no murmurs of, no hints” of concern by the government or among companies about the safety of these formulations.

A lot of “girlfriend conversations” have involved rethinking the idea of putting formulations with lye, an ingredient used in plumbing, on their heads, though there are plenty of no-lye options on the market.

Black women have reconsidered scalp-level issues, such as relaxer burns, scabbing, and hair loss, says Rooks, who is among the featured guests on Hulu’s The Hair Tales, Tracee Ellis Ross’s recent exploration of Black women’s notions of beauty and identity. Other guests include Oprah Winfrey, Chloe Bailey and the Massachusetts congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, among others.

“We hear about fibroids having something to do with relaxers,” Rooks says of the benign pelvic tumors Black women are two to three times more likely to suffer than white women. Fibroids are also the main reason women get hysterectomies, according to the Black Women’s Health Imperative. “So that has put the brakes on it as well.”

But Black women will continue to wrestle with the pressure to use relaxers to feel socially accepted, according to Alice Gresham, a Philadelphia-based clinical director for outpatient mental health. The Hair Tales makes “it clear the kind of trauma that we’ve been experiencing around a physical attribute secondary to our skin, which of course is still trauma, and it’s double trauma or complicated trauma,” Gresham tells TikTok viewers in a video responding to the Hulu series.

She says in professional settings, including at their jobs, Black women are subject to both hypervisibility – being scrutinized about everything from the work they do to how they look when doing it – and invisibility in being rewarded for good work. This duality produces “a psychosis in Black women in the workplace” trying to fit into corporate structures with the “right” look.

Gresham says she is incensed it is taking so long to make a federal law out of the Crown Act, which would make discrimination based on a person’s texture or style of hair illegal. The bill was co-sponsored by the Democratic representatives Ilhan Omar and Pressley, two Black women, and passed the House but stalled in the Senate. The Democratic New Jersey senator Cory Booker is expected to reintroduce the bill in the next Congress.

“The message is basically, it might be OK for you to do something different with your hair or be natural with your hair,” according to Gresham, who says trauma sets in when non-Black people “say the most ridiculous ignorant things to you about it, including trying to touch it or making comments in front of other people, asking you ‘Is that real?’ or ‘Your hair is so interesting how you have it in a different way each and every day.’”

Gresham says she has mentored women who struggle with thinning and brittle hair after years of relaxer use when the social acceptance they have been chasing hasn’t worked out the way they thought it would. “I believe there’s a bit of an attachment there, like ‘decent’ is relaxing, making it straight,” Greshman says. “We’re still struggling with natural hair in its natural way.”

No comments:

Post a Comment