The eccentric musician, dressed like a Viking playing songs on the streets of New York, is being celebrated by names such as Rufus Wainwright and Jarvis Cocker on a new album

Jim Farber

THE GUARDIAN

Most tourists who come to New York City for the first time seek out sights like the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty and Central Park. But between the early 60s and 1972, visitors with a more adventurous nature had a different agenda. “Certain people flying into the city at that time would jump into a cab and tell the driver – ‘take me to Moondog!’” said Robert Scotto, author of a book about the eccentric musician and composer who went by that luminous name. “The driver would take them straight to 6th Avenue and 53rd Street because everyone knew that’s where he was.”

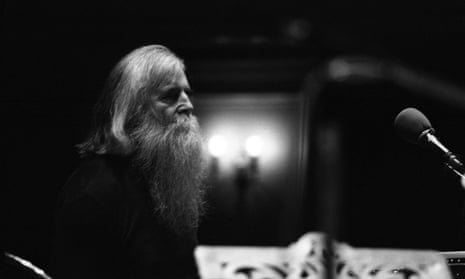

Certainly, no one who passed by that busy stretch of the city during that era could have missed him. Outfitted like a fantasy Viking, complete with a double-horned headdress, a doomy black tunic, an eight-foot spear and a long white beard, Moondog had an imposing presence to say the least. It only magnified the intensity of his appearance that he was blind, a fact he refused to hide behind dark glasses. From his reliable perch, Moondog would pull from his pockets reams of poetry, sheet music, 78rpm recordings and broadsides he had written to sell to curious passersby. Some people thought he was a freak or a vagrant. (He was, in fact, homeless during several short stretches of time.) Others saw him as the ultimate counter-cultural figure, while some major musicians viewed him as a visionary, including the jazz greats Benny Goodman and Charlie Parker and classical artists from Arturo Toscanini to Leonard Bernstein. Janis Joplin covered his existential composition All Is Loneliness, on her first album with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and pop acts from T-Rex to Prefab Sprout referenced him in their lyrics. Moondog was written up in many local and national papers and, in 1969 and 1971, he had two albums on Columbia Records which, at the time, was headquartered on the same block he haunted.

Today, it’s mainly musicians and fans of the arcane who have any awareness of Moondog at all – an oversight which inspired the creation of a new tribute album to amplify his legacy, titled Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog. The project was initiated by the Brooklyn-based jazz-chamber ensemble Ghost Train Orchestra in collaboration with the Kronos Quartet, and also features vocal performances from stars such as Rufus Wainwright, Jarvis Cocker and Joan as Policewoman. “Over the years, I’ve become a kind of evangelist for Moondog,” said Ghost Train Orchestra’s leader, Brian Carpenter. “I want more people to know about the joy and wonder of his music. And, luckily, there’s so much of it.”

Tue 26 Sep 2023

Most tourists who come to New York City for the first time seek out sights like the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty and Central Park. But between the early 60s and 1972, visitors with a more adventurous nature had a different agenda. “Certain people flying into the city at that time would jump into a cab and tell the driver – ‘take me to Moondog!’” said Robert Scotto, author of a book about the eccentric musician and composer who went by that luminous name. “The driver would take them straight to 6th Avenue and 53rd Street because everyone knew that’s where he was.”

Certainly, no one who passed by that busy stretch of the city during that era could have missed him. Outfitted like a fantasy Viking, complete with a double-horned headdress, a doomy black tunic, an eight-foot spear and a long white beard, Moondog had an imposing presence to say the least. It only magnified the intensity of his appearance that he was blind, a fact he refused to hide behind dark glasses. From his reliable perch, Moondog would pull from his pockets reams of poetry, sheet music, 78rpm recordings and broadsides he had written to sell to curious passersby. Some people thought he was a freak or a vagrant. (He was, in fact, homeless during several short stretches of time.) Others saw him as the ultimate counter-cultural figure, while some major musicians viewed him as a visionary, including the jazz greats Benny Goodman and Charlie Parker and classical artists from Arturo Toscanini to Leonard Bernstein. Janis Joplin covered his existential composition All Is Loneliness, on her first album with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and pop acts from T-Rex to Prefab Sprout referenced him in their lyrics. Moondog was written up in many local and national papers and, in 1969 and 1971, he had two albums on Columbia Records which, at the time, was headquartered on the same block he haunted.

Today, it’s mainly musicians and fans of the arcane who have any awareness of Moondog at all – an oversight which inspired the creation of a new tribute album to amplify his legacy, titled Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog. The project was initiated by the Brooklyn-based jazz-chamber ensemble Ghost Train Orchestra in collaboration with the Kronos Quartet, and also features vocal performances from stars such as Rufus Wainwright, Jarvis Cocker and Joan as Policewoman. “Over the years, I’ve become a kind of evangelist for Moondog,” said Ghost Train Orchestra’s leader, Brian Carpenter. “I want more people to know about the joy and wonder of his music. And, luckily, there’s so much of it.”

Moondog in 1972. Photograph: CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

In fact, when Moondog died in 1999 at 83, he left an archive filled with hundreds of compositions, many of which have yet to be transcribed or recorded. The range of the material in that archive, located in Münster, Germany, is broad and varied enough to embrace many kinds of music. “I always say that Moondog was a composer’s composer,” Carpenter said. “He wrote for string ensembles, percussion ensembles, solo percussionists, choirs, reeds, brass, but he also wrote pop songs with lyrics and jazz pieces. His work seems endless.”

To capture the dizzying and unusual range of sounds in his head, Moondog created his own instruments, much in the manner of another inventive American composer, Harry Partch. “Over time, his instruments became more and more elaborate,” Scotto said. “You would look at it and say, ‘how does one play this?’ And he was very fussy about their construction. It had to be a certain kind of wood and the cymbal had to be a certain kind of metal.”

His best-known invention was a triangle-shaped percussive contraption called the “trimba”. “You could get an enormous number of percussion sounds out of it by hitting different parts of the wood block,” Carpenter said.

There was also a triangular-shaped harp he called the “oo”, a stringed instrument named the “hüs” and more. Moondog made his own clothes too, many of which were modeled after Norse myth. It’s all a logical byproduct of a life based almost entirely on self-invention. The man who would become Moondog was born Louis Hardin in 1916 in Marysville, Kansas, to a religious family. His father, an Episcopalian minister, moved the family to Wyoming when the boy was young, and it was there that he discovered his first major musical influence, which came from Indigenous American culture. His eureka moment occurred after his father took him to an Arapaho Sun Dance where he met Chief Yellow Calf who showed him how to play a tom-tom made of buffalo skin. A lifelong fascination with rhythm was born. At 16, however, his life changed radically after he came across an object while playing that he didn’t realize was a dynamite cap. The device exploded in his face, blinding him. “Moondog later told me that for almost a year after that he felt as if he couldn’t breathe,” Scotto said. “The life had drained out of him.”

His sister was instrumental in rallying his spirits, reading to him works of philosophy and mythology that helped him form the character he would later become. While attending the Iowa School for the Blind he learned music, which he began to compose in braille. In 1943, he took that knowledge to New York where, shortly after he arrived, he adopted the name Moondog for a canine he knew who howled at the moon. He had yet to develop his Viking character when he began his career by recording his own compositions for small labels, some of which proved impressive enough to earn the attention of Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the New York Philharmonic, who invited him to perform with them.

In fact, when Moondog died in 1999 at 83, he left an archive filled with hundreds of compositions, many of which have yet to be transcribed or recorded. The range of the material in that archive, located in Münster, Germany, is broad and varied enough to embrace many kinds of music. “I always say that Moondog was a composer’s composer,” Carpenter said. “He wrote for string ensembles, percussion ensembles, solo percussionists, choirs, reeds, brass, but he also wrote pop songs with lyrics and jazz pieces. His work seems endless.”

To capture the dizzying and unusual range of sounds in his head, Moondog created his own instruments, much in the manner of another inventive American composer, Harry Partch. “Over time, his instruments became more and more elaborate,” Scotto said. “You would look at it and say, ‘how does one play this?’ And he was very fussy about their construction. It had to be a certain kind of wood and the cymbal had to be a certain kind of metal.”

His best-known invention was a triangle-shaped percussive contraption called the “trimba”. “You could get an enormous number of percussion sounds out of it by hitting different parts of the wood block,” Carpenter said.

There was also a triangular-shaped harp he called the “oo”, a stringed instrument named the “hüs” and more. Moondog made his own clothes too, many of which were modeled after Norse myth. It’s all a logical byproduct of a life based almost entirely on self-invention. The man who would become Moondog was born Louis Hardin in 1916 in Marysville, Kansas, to a religious family. His father, an Episcopalian minister, moved the family to Wyoming when the boy was young, and it was there that he discovered his first major musical influence, which came from Indigenous American culture. His eureka moment occurred after his father took him to an Arapaho Sun Dance where he met Chief Yellow Calf who showed him how to play a tom-tom made of buffalo skin. A lifelong fascination with rhythm was born. At 16, however, his life changed radically after he came across an object while playing that he didn’t realize was a dynamite cap. The device exploded in his face, blinding him. “Moondog later told me that for almost a year after that he felt as if he couldn’t breathe,” Scotto said. “The life had drained out of him.”

His sister was instrumental in rallying his spirits, reading to him works of philosophy and mythology that helped him form the character he would later become. While attending the Iowa School for the Blind he learned music, which he began to compose in braille. In 1943, he took that knowledge to New York where, shortly after he arrived, he adopted the name Moondog for a canine he knew who howled at the moon. He had yet to develop his Viking character when he began his career by recording his own compositions for small labels, some of which proved impressive enough to earn the attention of Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the New York Philharmonic, who invited him to perform with them.

To capture the dizzying and unusual range of sounds in his head, Moondog created his own instruments. Photograph: Dan Grossi

He also had an odd connection to the formative days of rock’n’roll. The seminal DJ Alan Freed named his show The Moondog Rock and Roll Matinee, and used the composer’s piece Moondog Symphony, as his theme song without credit. Moondog sued and won, preventing Freed from using the music or his name. At that time, Moondog was handsome, tall and gaunt, earning him the nickname “the man with the face of Christ”, a sobriquet that incensed him since he was anxious to rebel against the religion he grew up with. “Norse mythology was the exact opposite of what he saw as the facades of Christianity and the Greco-Roman tradition,” said Scotto. “But he wasn’t only drawn to it as a rebel. He also saw in it a great source of metaphor, poetry and, ultimately, musical adaptation.”

More, he recognized that the Viking get-up “was a great come-on”, Scotto said. “He knew it would get him attention and he definitely had a sense of humor about it.”

He chose to anchor his act on 6th Avenue in midtown Manhattan because so many jazz clubs and record labels were located in the area at the time. He became so well-known for occupying that spot that an advertisement in the 60s for the nearby Burlington Mills clothing company read, “come see us – right next to the Hilton Hotel and Moondog!”

Though Moondog usually eked out just enough money from selling his creations to keep a roof over his head – and, eventually, his life proved stable enough for him to marry several times and father a child – he sometimes lived on the streets. In the early 60s, his situation inspired the Village Voice to write an article that asked, “where are Moondog’s friends?” Scotto recalled. “Someone should take him in.”

That someone turned out to be the composer Philip Glass, who let him live on his couch for a year. In return, he got an important musical education. “Philip Glass told me that he learned more from Moondog than he did at Juilliard,” Scotto said.

There’s a clear correlation between Moondog’s compositional process and Glass’s trademark minimalism. “Glass’s music is very sparse and has an enormous amount of repetition, which is what Moondog did all the time,” Scotto said. “As a blind man he could only put a certain amount of information down at a certain time. He would use a large index card and get a complete piece on just that, which is why he often wrote rounds, canons and madrigals.”

He also had an odd connection to the formative days of rock’n’roll. The seminal DJ Alan Freed named his show The Moondog Rock and Roll Matinee, and used the composer’s piece Moondog Symphony, as his theme song without credit. Moondog sued and won, preventing Freed from using the music or his name. At that time, Moondog was handsome, tall and gaunt, earning him the nickname “the man with the face of Christ”, a sobriquet that incensed him since he was anxious to rebel against the religion he grew up with. “Norse mythology was the exact opposite of what he saw as the facades of Christianity and the Greco-Roman tradition,” said Scotto. “But he wasn’t only drawn to it as a rebel. He also saw in it a great source of metaphor, poetry and, ultimately, musical adaptation.”

More, he recognized that the Viking get-up “was a great come-on”, Scotto said. “He knew it would get him attention and he definitely had a sense of humor about it.”

He chose to anchor his act on 6th Avenue in midtown Manhattan because so many jazz clubs and record labels were located in the area at the time. He became so well-known for occupying that spot that an advertisement in the 60s for the nearby Burlington Mills clothing company read, “come see us – right next to the Hilton Hotel and Moondog!”

Though Moondog usually eked out just enough money from selling his creations to keep a roof over his head – and, eventually, his life proved stable enough for him to marry several times and father a child – he sometimes lived on the streets. In the early 60s, his situation inspired the Village Voice to write an article that asked, “where are Moondog’s friends?” Scotto recalled. “Someone should take him in.”

That someone turned out to be the composer Philip Glass, who let him live on his couch for a year. In return, he got an important musical education. “Philip Glass told me that he learned more from Moondog than he did at Juilliard,” Scotto said.

There’s a clear correlation between Moondog’s compositional process and Glass’s trademark minimalism. “Glass’s music is very sparse and has an enormous amount of repetition, which is what Moondog did all the time,” Scotto said. “As a blind man he could only put a certain amount of information down at a certain time. He would use a large index card and get a complete piece on just that, which is why he often wrote rounds, canons and madrigals.”

Rufus Wainwright, who recorded Moondog’s Be a Hobo for the Songs and Symphoniques tribute album.

Photograph: Miranda Penn Turin

The new tribute album surveys the full range of Moondog’s music, from madrigals to symphonic pieces to songs like All Is Loneliness. According to the Janis Joplin biographer Holly George-Warren, Loneliness came to Joplin via the Big Brother guitarist James Gurley who was a Moondog fan. Still, Scotto said the composer was disappointed by their version because “the song was written in 5/4 time, and they did it in 4/4.” The version on the tribute album, solemnly sung by Petra Haden, restores the original time signature.

Many other interpretations on the album take liberties with the original takes. Sam Amidon’s version of Behold turns it from a madrigal into an Americana folk ballad, while the cover of Down Is Up, emphasizes its proto-psychedelic chords. (The piece was written in the 1950s.) Other songs capture Moondog’s sense of whimsy, including Enough About Human Rights, whose lyrics playfully ask “what about goat rights?” and “what about lark rights?” Rufus Wainwright opens the album with a mantra of a piece, Be a Hobo. “It’s a song about letting go of our power so we can just be human,” said Wainwright, who also recorded Moondog’s song High on a Rocky Ledge for his latest album, Folkocracy. “When I first heard Moondog, it was a mystical event,” the singer said. “At first, you’re seduced by the simplicity of his music, but then you hear an underlying sophistication which is the hallmark of genius.”

The tribute album also honors Moondog’s love of street sounds by integrating car horns and pedestrian chatter into the music, just as he did. “He loved the natural world around him in a way that a blind person responds to it – by its sounds, not its sights,” Scotto said.

Despite its grounding in the external world, Moondog’s music also has an otherworldly feel, a sense emphasized by his visual presentation. “Like Sun Ra, Moondog created a cult of personality and a whole mythology around him,” Carpenter said. “There’s a cinematic feel to his music too, like the score to a movie nobody made.”

The efforts to spread the message of Moondog by Ghost Train Orchestra and the Kronos Quartet won’t end with this album. They’re planning a follow-up set and a tribute show at Carnegie Hall to take place in November. Moondog’s compelling backstory always helps in spreading the message, but Scotto says his essence lies elsewhere. “Listen to the music,” he said. “That’s where you’ll meet the man.”

Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog is out on 29 September

The new tribute album surveys the full range of Moondog’s music, from madrigals to symphonic pieces to songs like All Is Loneliness. According to the Janis Joplin biographer Holly George-Warren, Loneliness came to Joplin via the Big Brother guitarist James Gurley who was a Moondog fan. Still, Scotto said the composer was disappointed by their version because “the song was written in 5/4 time, and they did it in 4/4.” The version on the tribute album, solemnly sung by Petra Haden, restores the original time signature.

Many other interpretations on the album take liberties with the original takes. Sam Amidon’s version of Behold turns it from a madrigal into an Americana folk ballad, while the cover of Down Is Up, emphasizes its proto-psychedelic chords. (The piece was written in the 1950s.) Other songs capture Moondog’s sense of whimsy, including Enough About Human Rights, whose lyrics playfully ask “what about goat rights?” and “what about lark rights?” Rufus Wainwright opens the album with a mantra of a piece, Be a Hobo. “It’s a song about letting go of our power so we can just be human,” said Wainwright, who also recorded Moondog’s song High on a Rocky Ledge for his latest album, Folkocracy. “When I first heard Moondog, it was a mystical event,” the singer said. “At first, you’re seduced by the simplicity of his music, but then you hear an underlying sophistication which is the hallmark of genius.”

The tribute album also honors Moondog’s love of street sounds by integrating car horns and pedestrian chatter into the music, just as he did. “He loved the natural world around him in a way that a blind person responds to it – by its sounds, not its sights,” Scotto said.

Despite its grounding in the external world, Moondog’s music also has an otherworldly feel, a sense emphasized by his visual presentation. “Like Sun Ra, Moondog created a cult of personality and a whole mythology around him,” Carpenter said. “There’s a cinematic feel to his music too, like the score to a movie nobody made.”

The efforts to spread the message of Moondog by Ghost Train Orchestra and the Kronos Quartet won’t end with this album. They’re planning a follow-up set and a tribute show at Carnegie Hall to take place in November. Moondog’s compelling backstory always helps in spreading the message, but Scotto says his essence lies elsewhere. “Listen to the music,” he said. “That’s where you’ll meet the man.”

Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog is out on 29 September

No comments:

Post a Comment