SOCIAL EUROPE

EU policies on better law-making are tipping the scales in favour of businesses, marginalising social and environmental concerns.

Since the 1990s, the Europea Union has prioritised ‘better regulation’ and improved law-making. The European Commission has committed to making EU legislation clearer, simpler and more accessible to citizens.

My research—including a recent study commissioned by the Chamber of Labour Vienna—however shows that, under Ursula von der Leyen as commission president, the reduction of ‘burdens’ and ‘costs’ for businesses has taken centre stage. An analysis of all relevant EU official documents demonstrates a shift in the ‘better regulation’ agenda over time, favouring economic interests over social and environmental protection.

Deregulatory agenda

In the early 1990s, EU law was seen as overly technical and complex, prompting efforts to simplify and clarify it. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, EU legislation was increasingly viewed as a burden, especially for businesses, leading to a deregulatory agenda that often compromised societal standards.

Under von der Leyen’s predecessor, Jean-Claude Juncker (2014-19), while such concerns persisted policy solutions became more comprehensive. Tools such as REFIT (a regulatory-fitness and performance programme), the associated REFIT platform and the Regulatory Scrutiny Board were introduced, with a slightly more inclusive language than before.

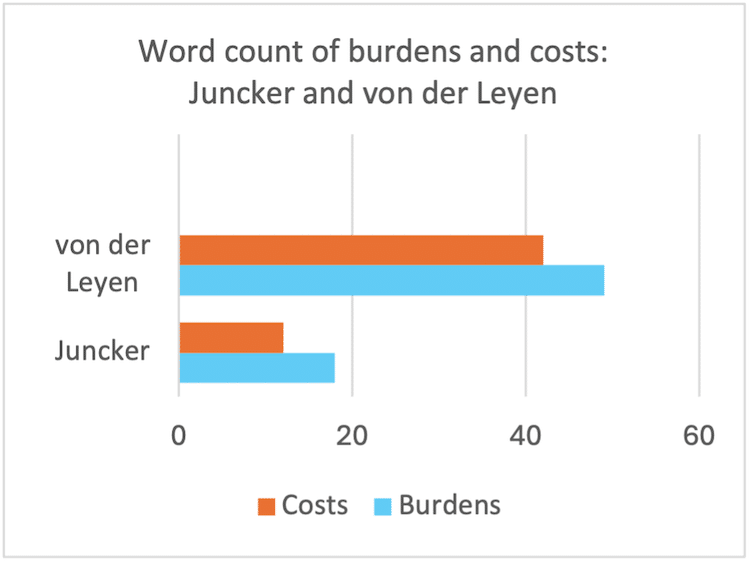

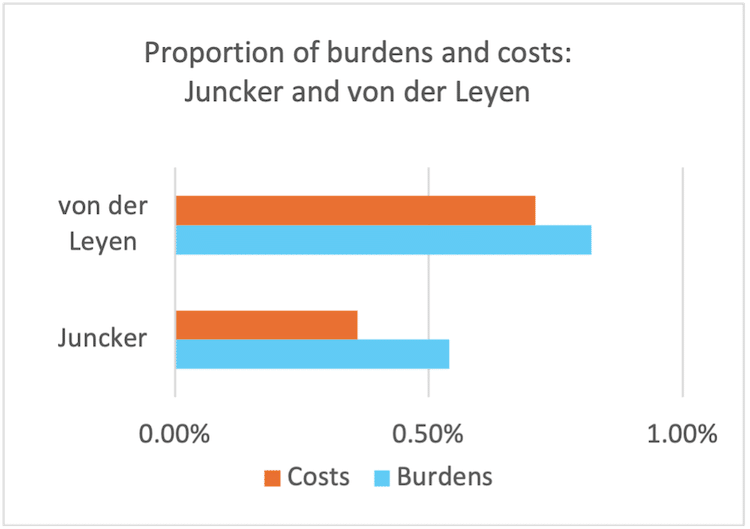

Under von der Leyen’s leadership, however, the commission has undergone a significant shift, prioritising business interests almost exclusively over broader societal concerns while framing EU legislation as too burdensome and costly. The charts below highlight a sharp increase in the focus on costs and burdens in the commission’s official language under von der Leyen, compared with Juncker.

Word count and proportion (%) of burdens and costs mentioned in European Commission communications under the Juncker and von der Leyen presidencies

Specifically, small and medium-sized enterprises have gained favourable conditions. Yet the commission’s definition of SMEs is so broad that 99.8 per cent of all companies in Europe fall into this category, including large enterprises that benefit from reduced obligations.

Even the Signa Holding property empire in Austria was classified as an SME and benefited from the lesser oversight associated with this deregulatory agenda. Signa declared bankruptcy last year—the largest insolvency in European property development—underscoring the dangers of relaxed regulation.

‘One in, one out’

Von der Leyen’s increasing focus on reducing burdens and costs has reshaped the solutions presented to address policy challenges, notably through a strong emphasis on the ‘one-In, one-out’ (OIOO) principle. This aims to balance any new regulations by eliminating a predecessor in the same policy area. Yet this is to view regulation one-sidedly, focusing solely on the costs of new rules (to be offset by retiring old ones) while overlooking the positive purpose of regulations and their value to society.

This approach risks undermining essential social and environmental standards, contradicting the ambitious goals of the European Green Deal and the European Pillar of Social Rights. Yet, despite criticism from the European Parliament and civil-society organisations, von der Leyen has prioritised OIOO and cost reduction, creating favourable conditions for businesses and SMEs which are increasingly exempt from control and reporting obligations, particularly in environmental areas.

A clear example is found in the the 2022 Annual Burden Survey, where the commission referred to EU legislation protecting workers from asbestos as a ‘burden’ on businesses—ignoring the benefits of safeguarding workers’ health, ensuring continued employment and maintaining contributions to social-security systems. The commission also overlooks the costs of failing to regulate, despite the 2008 global financial crisis showing that the consequences of insufficient regulation can be immense.

Same trajectory

The anticipated second term for von der Leyen will maintain this perspective in the five years ahead. For instance, the commission has confirmed that it will enhance efforts to reduce reporting obligations. The Letta and Draghi reports have meanwhile outlined plans to enhance ‘competitiveness’ and reduce regulatory ‘burdens’, especially for SMEs, reflecting von der Leyen’s policy direction. This could lead to more marketisation and privatisation in sectors such as transport and health, risking welfare systems and favouring corporate interests while creating more precarious working conditions across the EU.

The EU Strategic Agenda 2024-2029, adopted by the European Council in June, follows the same trajectory by focusing on security, competitiveness, SMEs and the single market as drivers of integration, while promoting financial integration and the elimination of single-market barriers. The agenda also addresses climate change and the digital transition but it remains vague on specifics beyond climate neutrality. Public health is marginalised—despite the recent pandemic—with only brief mentions of health co-operation. The 2019-2024 agenda had placed greater emphasis on social and consumer protection and on access to healthcare.

Overall, ‘better regulation’ will remain a key principle of the commission under von der Leyen, as she stresses the need to support European businesses in the global market by reducing their regulatory ‘burdens’. With her commission nominees significantly tilted towards the right, the social and environmental policy acquis will be at risk.

Brigitte Pircher

Brigitte Pircher is an associate professor at Södertörn University, Stockholm. Her research focuses on European Union institutions, policy-making and the implementation of EU policies in member states, with a particular emphasis on social policy and the internal market.

No comments:

Post a Comment