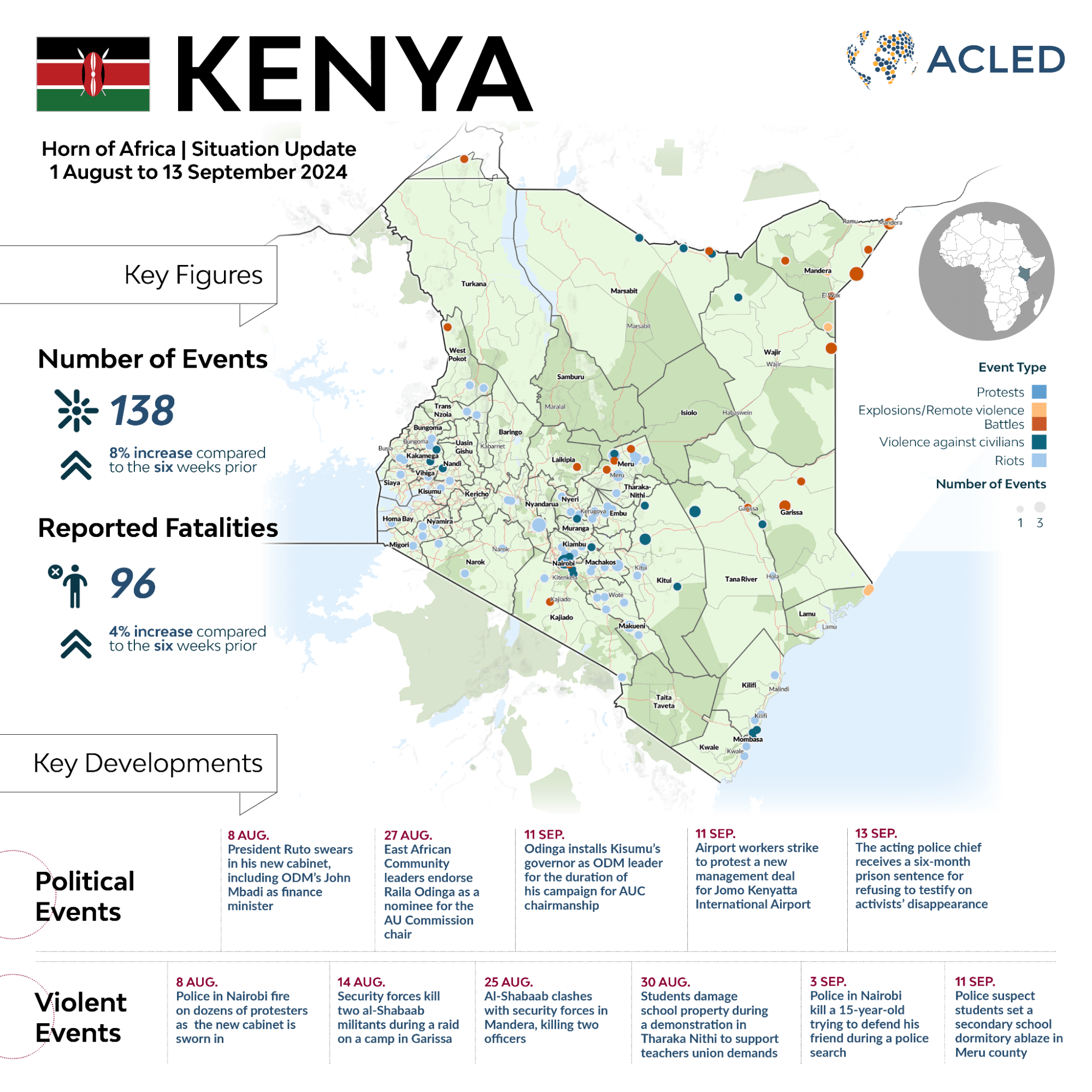

Over the summer, Kenya’s ‘Generation Z’ demonstrations against the government’s 2024 Finance Bill grew to encompass concerns about elite politics, corruption, and inequality. Operating without a recognizable figurehead and organizing online, the movement presented a significant challenge to the status quo. The protest movement scored a quick win when President William Ruto refused to sign the 2024 Finance Bill, sending it back to parliament on 26 June.1 Two weeks after that, he had dismissed all but one of his ministers.2 Through a combination of old-school elite bargaining, intimidation, and heavy-handed policing, President Ruto has broken the youth protest movement wave for now. Yet, these successes turned out to be short-lived. The debt crisis that the Finance Bill was supposed to address remains, and Kenya will likely need to borrow more just to maintain domestic and international debt repayments.3 At this stage, it is unclear whether popular discontent can be contained when public finances are under such strain.

Gen Z protests decrease

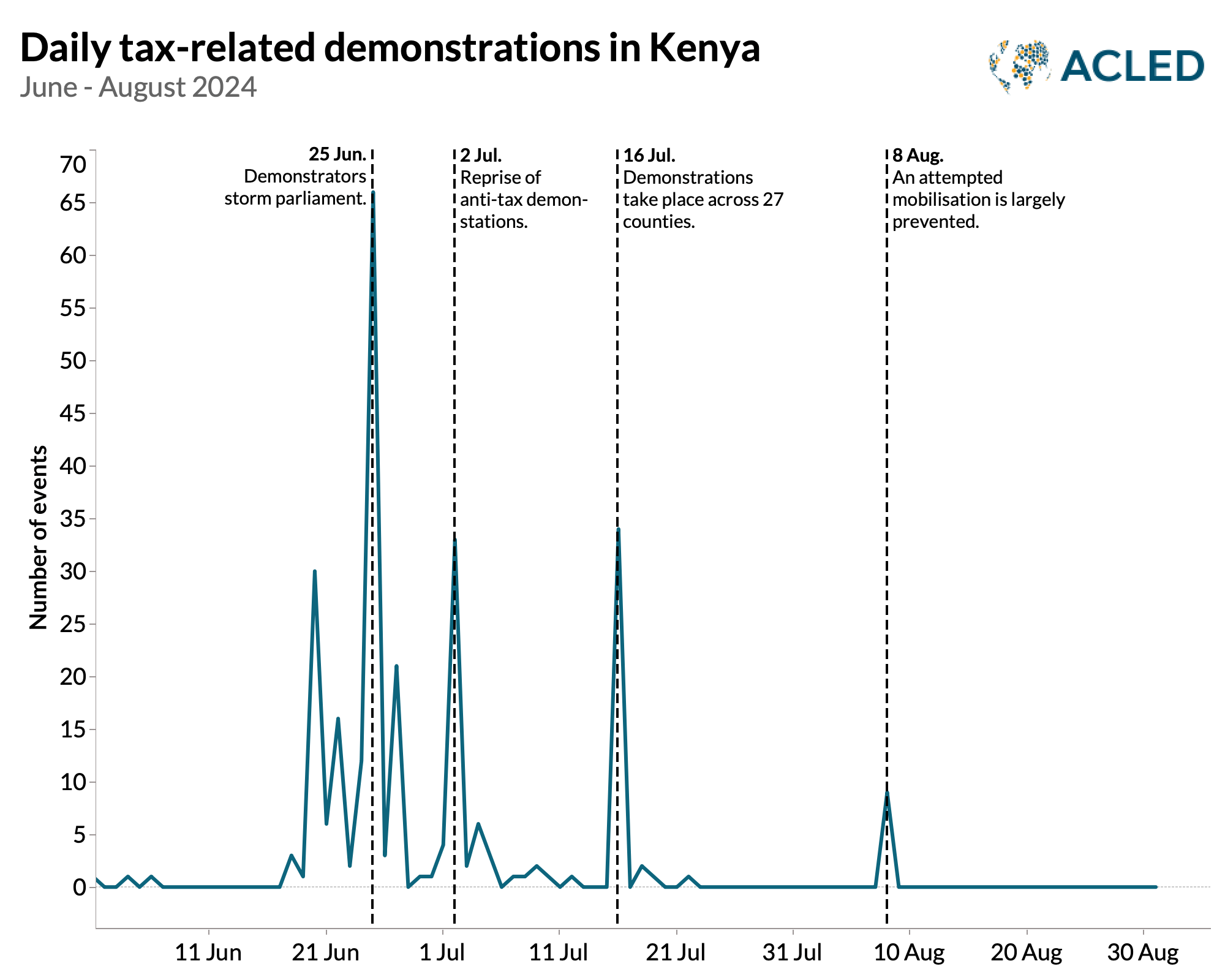

Youth demonstrations fell significantly in July and August. Demonstrations fell overall in July, notwithstanding demonstrations and street violence outbreaks on 2 and 16 July (see graph below). Events on 2 July were driven by dissatisfaction with the Finance Bill. By 16 July, the demonstrators’ concerns were more varied, encompassing corruption and lack of police accountability. Ruto’s cabinet reshuffling the previous week may have dampened protest.4 Following the withdrawal of the Finance Bill, that move likely diffused protestors’ concerns, contributing to a fall-off in events. The 16 July demonstrations occurred in 27 counties. The number of counties affected illustrates that, despite the initial crackdown, the movement retained some organizational capacity. Nevertheless, this was a contraction from 25 July, when 40 of Kenya’s 47 counties were affected. An attempted mobilization on 8 August — the day President Ruto swore in his new cabinet — was modest, with just nine events recorded in eight counties. Security forces successfully prevented protests planned across the country for that day by putting in place roadblocks and carrying out passenger checks outside main towns. In Nairobi, dozens of protestors at most turned out and were met with police force.5

Yet, nationwide mobilization declined only slightly. By August, demonstrations and protests organized by the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers strike outnumbered Gen Z protests by almost 10 to one. The strike was quickly resolved.6 This indicated a return to politics as mediating the interests of well-defined, organized interest groups, something the youth protests had challenged.

Elite bargaining, cooption, and intimidation

President Ruto’s response to the youth demonstrations was to build a coalition of political elites, co-opt influential individuals and groups, and intimidate organizers and participants. Building a traditional political coalition meant reaching out to his principal opponent, Raila Odinga. Taxation’s impact on the cost of living has been the issue around which opposition to President Ruto has organized since early 2023. Odinga, who was defeated as leader of the Azimio la Umoja coalition by less than 2% of the vote in the August 2022 presidential election, claimed Ruto’s government was illegitimate in January 2023.7 By the end of that year, he had identified taxation and the cost of living as the key issues for Azimio la Umoja.8 Street demonstrations led by Azimio la Umoja featured in 2023, with demonstrations spiking in July 2023 in response to that year’s Finance Bill. The state response to the 2023 demonstrations was notably violent, and President Ruto made no significant political compromise. However, the debt crisis facing the government and its domestic and international lenders heightened the urgency for political stability in the face of the Gen Z demonstrations of 2024. For Odinga, this presented an opportunity to move his own political party, the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), to the center of the administration and to satisfy his own ambition to secure the chair of the African Union Commission (AUC).

In 2024, President Ruto’s first response to the demonstrations was to send the Finance Bill back to parliament on 26 June, following the storming of parliament the previous day. By 24 July, a newly nominated cabinet included John Mbadi as finance minister.9 Mbadi had been a member of parliament from Homa Bay county and is the chairman of Odinga’s ODM party. The decision to share power with political elites has been viewed as a cynical move by President Ruto.10 However, there were no significant protests in immediate response to the appointments.

Odinga had signaled his willingness to shore up President Ruto’s administration on 9 July, when he agreed to participate in a National Multi-Sectoral Dialogue Forum established by President Ruto to address the crisis.11 Furthermore, the installation of Mbadi as finance minister signaled that Odinga’s political weight was being put behind President Ruto. In return, in August, President Ruto ensured Odinga’s endorsement as the agreed East Africa region candidate for the position of chair of the AUC.12 Data suggest the demonstrations presented a threat to Raila Odinga as much as they did to President Ruto. Azimio la Umoja dominated the demonstrations in 2023. In July 2023, it was involved in almost all such events. However, in July 2024, it was entirely absent. In opposing President Ruto, the youth demonstrators also took Odinga’s political ground, challenging the traditional dominance of Kenya’s elite politics.

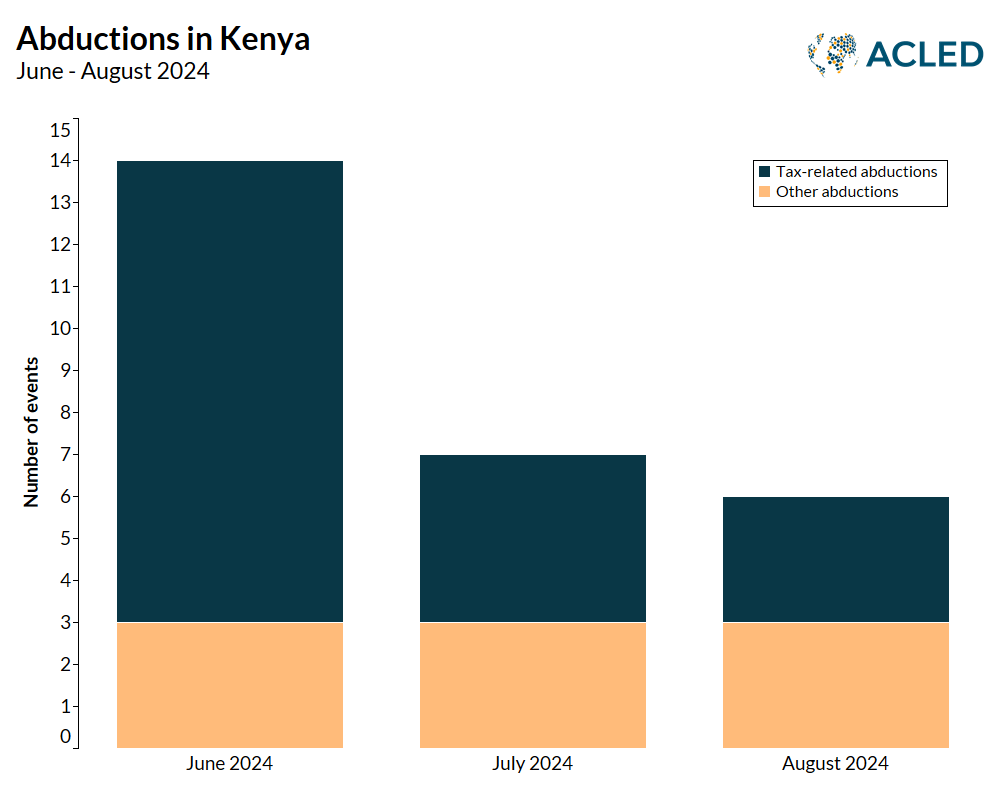

Policing protest — through excessive force against demonstrators and abductions — was a key element of the response to the demonstrations against the 2024 Finance Bill, followed by efforts to co-opt or otherwise intimidate opponents. Through June, July, and August, there was a steady stream of targeted abductions (see graph below). Of 27 abductions recorded by ACLED for June, July, and August, at least 19 were likely related to the protests and were likely undertaken by police. Most of these were on or around 25 June, the day the parliament was overrun. The abductions are currently being investigated by the Police Oversight Investigations Authority.13 In a case brought by the Law Society of Kenya (LSK), acting Inspector General of Police, Gilbert Masengele, has been found to be in contempt of court for not appearing to answer questions about the abductions of protestors, as ordered by the High Court on 23 August.14

On the morning of 25 June, the personal assistant to Faith Odhiambo, president of the LSK, was abducted. In the week before his abduction, the LSK had objected to police banning anti-tax protests.15 The LSK had emerged as a key player in the demonstrations, establishing a legal aid fund to support a network of lawyers it put in place to provide legal representation to arrested demonstrators and others targeted by the state during the unrest.16 Others targeted included social media influencers and people providing medical assistance to demonstrators.17

In July, President Ruto took a different approach and offered LSK’s Odhiambo a position on a proposed Presidential Task Force on Forensic Audit of Public Debt. Odhiambo refused the offer, arguing it would usurp the constitutional role of the Auditor-General.18

This suite of extra-legal and potentially extra-constitutional measures has slowed the Gen Z movement and the organizations that supported it. The cabinet’s dismissal and the Finance Bill’s withdrawal were quick wins, but maintaining such momentum was unlikely. Simply coordinating between the various organizations and individuals involved would be hard to maintain: the Police Reforms Working Group alone, which protested the initial disappearances in June, comprises at least 20 member organizations.19

A budget deficit means protests will re-emerge

The new taxes introduced in the original 2024 Finance Bill were a crude way of addressing the country’s debt crisis. Expenditure cutbacks introduced in the supplementary budget that replaced the act are not enough to stave off increased borrowing needed to pay off old debts.20 Protests by teachers and the related strike were mostly peaceful, and the dispute was resolved.21 However, as the budget deficit is likely to worsen in the coming year, President Ruto’s administration will have less fiscal space to meet such demands from other organized groups.22 Furthermore, he will have no room to improve expenditure on public services, which has been declining in recent years and fueled popular discontent with the Finance Bill this year.

The bargain between Odinga and President Ruto may turn out to be destabilizing. Not all members of the Azimio la Umoja coalition agreed with Odinga’s recent stance toward Ruto, and support was not universal within Odinga’s ODM party, either.23 If Odinga is successful in his AUC campaign, the arrangement may not hold. If unsuccessful, he may appear weakened on return and less capable of dealing with the divisions he left behind.

As the cost of living pressures remain, protests will remain a feature of Kenya’s political life. As for the youth movement, civil society organizations and individual leaders who were involved in the demonstrations will have learned much about organization, protest, and how to channel popular discontent. How this shapes political protest in the future remains to be seen.

No comments:

Post a Comment