ASSANGE TRIAL REPORTING

Imperial Venality Defends Itself: Day Two of Julian Assange’s High Court Appeal

On February 21, the Royal Courts of Justice hosted a second day of carnivalesque mockery regarding the appeal by lawyers representing an ill Julian Assange, whose publishing efforts are being impugned by the United States as having compromised the identities of informants while damaging national security. Extradition awaits, only being postponed by rearguard actions such as what has just been concluded at the High Court.

How, then, to justify the 18 charges being levelled against the WikiLeaks founder under the US Espionage Act of 1917, an instrument not just vile but antiquated in its effort to stomp on political discussion and expression?

Justice Jeremy Johnson and Dame Victoria Sharp got the bien pensant treatment of the national security state, dressed in robes, and tediously inclined. Prosaic arguments were recycled like stale, oppressive air. According to Clair Dobbin KC, there was “no immunity for journalists to break the law” and that the US constitutional First Amendment protecting the press would never confer it. This had an undergraduate obviousness to it; no one in this case has ever asserted such cavalierly brutal freedom in releasing classified material, a point that Mark Summers KC, representing Assange, was happy to point out.

Yet again, the Svengali argument, gingered with seduction, was run before a British court. Assange, assuming all the powers of manipulation, cultivated and corrupted the disclosers, “soliciting” them to pilfer classified government materials. With limping repetition, Dobbin insisted that WikiLeaks had been responsible for revealing “the unredacted names of the sources who provided information to the United States,” many of whom “lived in war zones or in repressive regimes”. In exposing the names of Afghans, Iraqis, journalists, religious figures, human rights dissidents and political dissidents, the publisher had “created a grave and immediate risk that innocent people would suffer serious physical harm or arbitrary detention”.

The battering did not stop there. “There were really profound consequences, beyond the real human cost and to the broader ability to the US to gather evidence from human sources as well.” Dobbin’s proof of these contentions is thin, vague and causally absent: the arrest of one Ethiopian journalist following the leak; unspecified “others” disappeared. She even admitted the fact that “it cannot be proven that their disappearance was a result of being outed.” This was certainly a point pounced upon by Summers.

The previous publication by Cryptome of all the documents, or the careless publication of the key to the encrypted file with the unredacted cables by journalists from The Guardian in a book on WikiLeaks, did not convince Dobbin. Assange was “responsible for the publications of the unredacted documents whether published by others or WikiLeaks.” There was no mention, either, that Assange had been alarmed by The Guardian faux pas and had contacted the US State Department of this fact. Summers, in his contribution, duly reminded the court of the publisher’s frantic efforts while also reasoning that the harm caused had been “unintended, unforeseen and unwanted” by him.

With this selective, prejudicial angle made clear, Dobbin’s words became those of a disgruntled empire caught with its pants down when harming and despoiling others. “What the appellant is accused of is really at the upper end of the spectrum of gravity,” she submitted, attracting “no public interest whatsoever”. Conveniently, calculatingly, any reference to the enormous, weighty revelations of WikiLeaks of torture, renditions, war crimes, surveillance, to name but a few, was avoided. Emphasis was placed, instead, upon the “usefulness” of the material WikiLeaks had published: to the Taliban, and Osama bin Laden.

This is a dubious point given the Pentagon’s own assertions to the contrary in a 2011 report dealing with the significance of the disclosure of military and diplomatic documents by WikiLeaks. On the Iraq War logs and State Department cables, the report concluded “with high confidence that disclosure of the Iraq data set will have no direct personal impact on current and former US leadership in Iraq.” On the Afghanistan war log releases, the authors also found that they would not result in “significant impact” to US operations, though did claim that this was potentially damaging to “intelligence sources, informants, and the Afghan population,” and intelligence collection efforts by the US and NATO.

Summers appropriately rebutted the contention about harm by suggesting that Assange had opposed, in the highest traditions of journalism, “war crimes”, a consideration that had to be measured against unverified assertions of harm.

On this point, the prosecution found itself in knots, given that a balancing act of harm and freedom of expression is warranted under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. When asked by Justice Johnson whether prosecuting a journalist in the UK, when in possession of “information of very serious wrongdoing by an intelligence agency [had] incited an employee of that agency to provide information… [which] was then published in a very careful way” was compatible with the right to freedom of expression, Dobbin conceded to there being no “straightforward answer”.

When pressed by Justice Johnson as to whether she accepted the idea that the “statutory offence”, not any “scope for a balancing exercise” was what counted, Dobbin had to concede that a “proportionality assessment” would normally arise when publishers were prosecuted under section 5 of the UK Official Secrets Act. Prosecutions would only take place if one “knowingly published” information known “to be damaging”.

Any half-informed student of the US Espionage Act knows that strict liability under the statute negates any need to undertake a balancing assessment. All that matters is that the individual had “reason to believe that the information is to be used to the injury of the US,” often proved by the mere fact that the information published was classified to begin with.

Dobbin then switched gears. Having initially advertised the view that journalists could never be entirely immune from criminal prosecution, she added more egg to the pudding on the reasons why Assange was not a journalist. Her view of the journalist being a bland, obedient transmitter of received, establishment wisdom was all too clear. Assange had gone “beyond the acts of a journalist who is merely gathering information”. He had, for instance, agreed with Chelsea Manning on March 8, 2010 to attempt cracking a password hash that would have given her access to the secure and classified Department of Defense account. Doing so meant using a false identity to facilitate further pilfering of classified documents.

This was yet another fiction. Manning’s court martial had revealed the redundancy of having to crack a password hash as she already had administrator access to the system. Why then bother with the conspiratorial circus?

The corollary of this is that the prosecution’s reliance on fabricated testimony, notably from former WikiLeaks volunteer, convicted paedophile and FBI tittle-tattler Sigurdur ‘Siggi’ Thordarson. In June 2021, the Icelandic newspaper Stundin, now publishing under the name Heimildin, revealed that Assange had “never asked him to hack or to access phone recordings of [Iceland’s] MPs.” He also had not “received some files from a third party who claimed to have recorded MPs and had offered to share them with Assange without having any idea what they actually contained.” Thordarson never went through the relevant files, nor verified whether they had audio recordings as claimed by the third-party source. The allegation that Assange instructed him to access computers in order to unearth such recordings was roundly rejected.

The legal team representing the US attempted to convince the court that suggestions of “bad faith” by the defence on the part of such figures as lead prosecutor Gordon Kromberg had to be discounted. “The starting position must be, as it always is in these cases, the fundamental assumption of good faith on the part of those states with which the United Kingdom has long-standing extradition relationships,” asserted Dobbin. “The US is one of the most long-standing partners of the UK.”

This had a jarring quality to it, given that nothing in Washington’s approach to Assange – the surveillance sponsored by the Central Intelligence Agency via Spanish security firm UC Global, the contemplation of abduction and assassination by intelligence officials, the after-the-fact concoction of assurances to assure easier extradition to the US – has been anything but one of bad faith.

Summers countered by refuting any suggestions that “Mr Kronberg is a lying individual or that he is personally not carrying out his prosecutorial duties in good faith. The prosecution and extradition here is a decision taken way above his head.” This was a matter of “state retaliation ordered from the very top”; one could not “focus on the sheep and ignore the shepherd.”

Things did not get better for the prosecuting side on what would happen once Assange was extradited. Would he, for instance, be protected by the free press amendment under US law? Former CIA director Mike Pompeo had suggested that Assange’s Australian citizenship barred him from protections afforded by the First Amendment. Dobbin was not sure, but insisted that there was insufficient evidence to suggest that nationality would prejudice Assange in any trial. Justice Johnson was sharp: “the test isn’t that he would be prejudiced. It is that he might be prejudiced on the grounds of his nationality.” This was hard to square with the UK Extradition Act prohibiting extradition where a person “might be prejudiced at his trial or punished, detained, or restricted in his personal liberty” on account of nationality.

Given existing US legal practice, Assange also faced the risk of the death penalty, something that extradition arrangements would bar. Ben Watson KC, representing the UK Home Secretary, had to concede to the court that there was nothing preventing any amendment by US prosecutors to the current list of charges that could result in a death sentence.

If he does not succeed in this appeal, Assange may well request an intervention of the European Court of Human Rights for a stay of proceedings under Rule 39. Like many European institutions so loathed by the governments of post-Brexit Britain, it offers the prospect of relief provided that there are “exceptional circumstances” and an instance “where there is an imminent risk of irreparable harm.”

The sickening irony of that whole proviso is that irreparable harm is being inflicted on Assange in prison, where the UK prison system fulfils the role of the punishing US gaoler. Speed will be of the essence; and the government of Rishi Sunak may well quickly bundle the publisher onto a transatlantic flight. If so, the founder of WikiLeaks will go the way of other prestigious and wronged political prisoners who sought to expand minds rather than narrow them.

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com. Read other articles by Binoy.

In this video, we summarize the main points addressed by Assange’s defence council during what may be the final appeal hearing in the case of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. The outcome of this case will determine if Assange can appeal once more before a UK court or if he enters the extradition process. The defence raised several grounds for appeal before two High Court judges. This was the first time the defence team had an opportunity to present their arguments, which countered some aspects of the district judge’s initial ruling.

By Chris Hedges

Kangaroo Courtship - by Mr. Fish

The prosecution lawyers in the High Court seeking to ensure Julian’s extradition to the U.S. rely almost exclusively on the judicial opinions of Gordon Kromberg, a highly controversial U.S. attorney.

The prosecution for the U.S., which is seeking to deny Julian Assange’s appeal of an extradition order, begun by the Trump administration and embraced by the Biden administration, grounded its arguments on Wednesday in the dubious affidavits filed by a U.S. federal prosecutor in the Eastern District of Virginia, Gordon Kromberg.

The charges articulated by Kromberg — often false — to make the case for extradition did not fly with the two High Court judges, Jeremy Johnson and Dame Victoria Sharp, who are overseeing Julian’s final appeal in the British courts.

The prosecuting attorneys, under questioning from the judges, were knocked off balance when challenged about the veracity of several of the claims which Kromberg made in support of the indictment against Julian. This was especially the case when the attorneys argued that the classified documents Julian released in 2010 — known as the Iraq and Afghan war logs — were not redacted. These unredacted documents, they told the court, jeopardized the lives of those named in the documents and caused some to “disappear.”

As defense lawyers Edward Fitzgerald KC and Mark Summers KC made clear, and the judges seemed to acknowledge, the documents were indeed redacted by Julian as he worked with media partners, such as The Guardian and The New York Times, when WikiLeaks published classified military documents concerning the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, along with U.S. State Department cables. The unredacted versions were first published by the website Cryptome after two reporters from The Guardian published a book with the passcode to the documents, leading to their publication by other online organizations.

Julian contacted the US government, as Summers told the court, and spoke to them at length, in an attempt to prevent the unredacted cables from being published. In the end, the U.S. State Department chose not to act. U.S. officials have sheepishly admitted they have no evidence of anyone named in the documents being harmed. Other allegations — such as that Julian tried to help Chelsea Manning, who leaked the documents, decode a password hash to access documents or protect her identity, or that he sought to conspire with computer hackers — have also been debunked.

A report provided to Judge Baraitser by a U.S. military forensic expert found that even if Manning was able to decode the password hash (which neither she nor anyone at WikiLeaks ever did) it would not have provided access to documents, it would not have provided her with anonymity and it would not have given her access to documents which she did not already have. The expert also described that someone with Manning’s technical knowledge, skill and experience, as well as her lawful access to Top Secret materials, would have known this. But these Kromberg-inspired canards are all the U.S. has, so it uses them.

By the end of the day, it seemed likely that, probably by April, since requested written briefs have to be turned into the judges in March, the two judges will permit an appeal on at least a few of the points. This will, conveniently for the Biden administration — which I expect does not want to take on the contentious issue of extraditing Julian while fueling the genocide in Gaza — mean that any extradition would occur after the election.

The two-day hearing was Julian’s last chance to request an appeal of the extradition decision made in 2022 by the then British home secretary, Priti Patel and of many of the rulings of District Judge Vanessa Baraitser in 2021. If Julian is denied an appeal he can request the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for a stay of execution under Rule 39, which is given in “exceptional circumstances” and “only where there is an imminent risk of irreparable harm.” But it is possible the British court could order Julian’s immediate extradition prior to a Rule 39 instruction or decide to ignore a request from the ECtHR to allow Julian to have his case heard by the court.

The CIA seeks Julian’s imprisonment in the U.S. because of the release of the documents known as Vault 7, which exposed hacking tools that permit the CIA to access our phones, computers and televisions, turning them — even when switched off — into monitoring and recording devices. The formal extradition request does not include charges based on the release of the Vault 7 files, but the U.S. request also only came after the release of the Vault 7 material. The CIA usually gets what it wants. But for the near future I expect Julian to continue to rot in HM Prison Belmarsh, where he has been imprisoned for nearly five years as he deteriorates physically and psychologically. This slow motion execution is intentional.

It is hard to call any court ruling, other than the dropping of the charges against him, a victory, but the longer he stays out of U.S. hands, the more hope he has of regaining his freedom for carrying out the most important investigative journalism of our generation.

Prosecution attorney Clair Dobbin KC, her long blonde hair spilling out from under her official curled blonde court wig, clung to the Kromberg affidavit like the holy grail, reading sections of it to the court.

“It is not part of the ordinary responsibilities of journalists to actively solicit and publish classified information,” she told the court, in one of her most obtuse statements.

The core charges, she said, echoing Kromberg, were “complicity in illegal acts to obtain or receive voluminous databases of classified information;” the attempt to “obtain classified information through computer hacking” and “publishing certain documents that contained the un-redacted names of innocent people who risked their safety and freedom to provide information to the United States and its allies, including local Afghans and Iraqis, journalists, religious leaders, human rights advocates, and political dissidents from repressive regimes.”

Of course, as Julian’s defense pointed out, many of these people were informants, aiding and abetting U.S. war crimes, but the phrase “war crimes” was never mentioned by the prosecution, magically erased from the case.

The prosecution, relying on Kromberg, insisted Julian was not a journalist, that what he published was “not in the public interest” and that the U.S. was not seeking his extradition on political grounds. They charged that “hostile foreign governments, terrorist groups, and criminal organizations have exploited WikiLeaks disclosures in order to gain intelligence to be used against the United States and to be used against foreign nationals who provided assistance to the United States.” They said that Osama bin Laden had requested the material posted by WikiLeaks and that the Taliban used the documents to identify informants.

I first encountered Kromberg — a fervent Zionist with ties to Israel’s far-right settler movement in the occupied West Bank — when in the wake of the attacks of 9/11, the U.S. government began imprisoning leading Palestinian activists as “terrorists” and shutting down Palestinian charities such as The Holy Land Foundation.

Kromberg served as the Grand Inquisitor in these witch hunts, going after numerous Muslims including Ahmed Abu Ali, as well as my friend, the Palestinian professor and activist Dr. Sami al-Arian.

Al-Arian endured a six-month show trial in Florida – not unlike Julian’s – that saw the government’s case collapse in a mass of contradictions and innuendo. During the trial the government called 80 witnesses and subjected the jury to hundreds of hours of often inane phone transcriptions and recordings, made over a 10-year period, which the jury dismissed as “gossip.” Out of the 94 charges made against the four defendants, there were no convictions. Of the 17 charges against al-Arian — including “conspiracy to murder and maim persons abroad” — the jury acquitted him of eight and was hung on the rest. The jurors disagreed on the remaining charges by a count of 10 to 2, favoring his full acquittal.

Following the acquittal, the Palestinian professor, under duress, accepted a plea bargain agreement that would spare him a second trial, saying in his agreement that he had helped people associated with Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the second largest resistance organization in Gaza and the West Bank, with immigration matters. He was sentenced to 57 months in prison. Al-Arian, while imprisoned, was ordered by Kromberg to testify in the grand jury investigation of the International Institute of Islamic Thought in Herndon, Virginia.

When al-Arian’s lawyers asked Kromberg to delay the transfer of the professor to Virginia because of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, Kromberg told them “if they can kill each other during Ramadan they can appear before the grand jury.” Kromberg, according to an affidavit signed by al-Arian’s attorney, Jack Fernandez, also said: “I am not going to put off Dr. al-Arian’s grand jury appearance just to assist in what is becoming the Islamization of America.”

The government wasted $80 million trying to convict Dr. al-Arian, who refused Kromberg’s demand that he testify and was charged with contempt. He was eventually deported and lives in Turkey.

“In 2017, Kromberg prosecuted the case of a D.C. police officer accused of buying gift cards in support of terrorism, charges that arose from a controversial sting operation,” The Intercept noted. “In court, Kromberg leveled eyebrow-raising allegations that the suspect was both a supporter of the jihadist group Islamic State as well as the World War II-era German Nazi Party on the grounds that he owned historical paraphernalia. Referring to an anonymous online commenter who had called the defendant “Muslim-Nazi scum,” Kromberg argued in court, “Whether or not that’s true, I don’t know the answer to that. But the point is that the Nazi stuff in this case is very much related to the, to the ISIS stuff.”

Kromberg has as deep an animus for Julian — and one suspects journalists — as he does for Muslims.

He raises the possibility, a possibility rather foolishly repeated by the prosecution’s representatives in London, that Julian, as a foreign national, could be denied First Amendment protections if tried in the U.S. This prompted the judges to ask if they had “any evidence that a foreign national is entitled to the same rights [under the First Amendment] as a U.S. citizen,” a question Dobbin, fumbling, was unable to answer.

At the same time, Kromberg has offered numerous assurances, repeated by the prosecution on Wednesday, that Julian will not be subjected to harsh prison conditions. He called the possibility that Julian will be housed in a highly restrictive supermax prison “purely speculative.”

Kromberg subpoenaed Manning in 2019 to testify before a grand jury in an effort to get her to implicate Julian in “one count of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion,” a charge which was thoroughly debunked by expert testimony in 2020. Manning appeared before the grand jury but refused to answer questions posed to her. She was held in civil contempt and incarcerated. She was released after the grand jury expired. Kromberg then served her with a second subpoena to appear before another grand jury. Again she refused to testify, leading to another round of incarceration and fines of $500 a day that were raised to $1,000 a day after 60 days of noncompliance. In March of 2020 while being housed in a detention center in Alexandria, Virginia, she was hospitalized after she attempted to commit suicide.

The effort to force Manning to implicate Assange is central to the U.S. case. If they can convince the court that Julian agreed to assist Manning in cracking a passcode to access a Department of Defense computer connected to the Secret Internet Protocol Network, used for classified documents and communications, it would allow the government to charge Julian with an actual crime.

The fatal flaw in the case against Julian is that he did not commit a crime. He exposed the crimes of others. Those who ordered and carried out these crimes are determined, no matter how they have to deform the British and U.S. legal systems, to make him pay.

Related Posts

Karen Sharpe -- February 20, 2024

Julian Assange’s Final Appeal

Chris Hedges -- February 19, 2024

“Free the Truth”: The Belmarsh Tribunal on Julian Assange & Defending Press Freedom

Amy Goodman -- January 01, 2024

Assange: An Unholy Masquerade of Tyranny Disguised as Justice

Craig Murray -- June 16, 2023

The Imminent Extradition of Julian Assange and the Death of Journalism

Chris Hedges -- June 19, 2023

Chris Hedges who graduated from seminary at Harvard Divinity School, worked for nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times, National Public Radio and other news organizations in Latin America, the Middle East and the Balkans. He was part of the team of reporters at The New York Times who won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of global terrorism. Hedges is a fellow at the Nation Institute and the author of numerous books, including War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.

By Craig Murray

Reporting on Julian Assange’s extradition hearings has become a vocation that has now stretched over five years. From the very first hearing, when Justice Snow called Assange “a narcissist” before Julian had said anything whatsoever other than to confirm his name, to the last, when Judge Swift had simply in 2.5 pages of glib double-spaced A4 dismissed a tightly worded 152-page appeal from some of the best lawyers on earth, it has been a travesty and charade marked by undisguised institutional hostility.

We were now on last orders in the last chance saloon, as we waited outside the Royal Courts of Justice for the appeal for a right of final appeal.

The architecture of the Royal Courts of Justice was the great last gasp of the Gothic revival; having exhausted the exuberance that gave us the beauty of St Pancras Station and the Palace of Westminster, the movement played out its dreary last efforts at whimsy in shades of gray and brown, valuing scale over proportion and mistaking massive for medieval. As intended, the buildings are a manifestation of the power of the state; as not intended, they are also an indication of the stupidity of large scale power.

Court number 5 had been allocated for this hearing. It is one of the smallest courts in the building. Its largest dimension is its height. It is very high, and lit by heavy mock medieval chandeliers hung by long cast iron chains from a ceiling so high you can’t really see it. You expect Robin Hood to suddenly leap from the gallery and swing across on the chandelier above you. The room is very gloomy; the murky dusk hovers menacingly above the lights like a miasma of despair, below them you peer through the weak light to make out the participants.

A huge tiered walnut dais occupies half the room, with the judges seated at its apex, their clerks at the next level down, and lower lateral wings reaching out, at one side housing journalists and at the other a huge dock for the prisoner or prisoners, with a massy iron cage that looks left over from a production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

This is in fact the most modern part of the construction; caging defendants in medieval style is in fact a Blair era introduction to the so-called process of law.

Rather incongruously, the clerks’ tier was replete with computer hardware, with one of the two clerks operating behind three different computer monitors and various bulky desktop computers, with heavy cables twisting in all directions like sea kraits making love. The computer system seems to bring the court into the 1980’s, and the clerk behind it looked uncannily like a member of a synthesiser group of that era, right down to the upwards pointing haircut.

In period keeping, this computer feed to an overflow room did not really work, which led to a number of halts in proceedings.

All the walls are lined with high bookcases housing thousands of leather bound volumes of old cases. The stone floor peeks out for one yard between the judicial dais and the storied wooden pews, with six tiers of increasingly narrow seating. The barristers occupied the first tier and their instructing solicitors the second, with their respective clients on the third. Up to ten people per line could squeeze in, with no barriers on the bench between opposing parties, so the Assange family was squashed up against the CIA, State Department and UK Home Office representatives.

That left three tiers for media and public, about thirty people. There was however a wooden gallery above which housed perhaps twenty more. With little fuss and with genuine helpfulness and politeness, the court staff – who from the Clerk of Court down were magnificent – had sorted out the hundreds of those trying to get in, and we had the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, we had 16 Members of the European Parliament, we had MPs from several states, we had NGOs including Reporter Without Borders, we had the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers, and we had, (checks notes) me, all inside the Court.

I should say this was achieved despite the extreme of official unhelpfulness from the Ministry of Justice, who had refused official admission and recognition to all of the above, including the United Nations. It was pulled together by the police, court staff and the magnificent Assange volunteers led by Jamie. I should also acknowledge Jim, who with others spared me the queue all night in the street I had undertaken at the International Court of Justice, by volunteering to do it for me.

This sketch captures the tiny non-judicial portion of the court brilliantly. Paranoid and irrational regulations prevent publications of photos or screenshots.

My rough sketch while trying to listen on a difficult audio feed.

At front two Counsels for #Assange, to right behind them Gareth Perice, then from right John Shipton, @GabrielShipton, @Stella_Assange, behind them @ChrisLynnHedges. Also saw @CraigMurrayOrg and @suigenerisjen. pic.twitter.com/pNI2mHMRHW— Matt Ó Branáin (@MattOBranain) February 20, 2024

The acoustics of the court are simply terrible. We are all behind the barristers as they stood addressing the judges, and their voices were at the same time muffled yet echoing from the bare stone walls.

I did not enter with a great deal of hope. As I have explained in How the Establishment Functions, judges do not have to be told what decision is expected by the Establishment. They inhabit the same social milieu as ministers, belong to the same institutions, attend the same schools, go to the same functions. The United States’ appeal against the original blocking of Assange’s extradition was granted by a Lord Chief Justice who is the former room-mate, and still best friend, of the minister who organised the removal of Julian from the Ecuadorean Embassy.

The blocking of Assange’s appeal was done by Judge Swift, a judge who used to represent the security services, and said they were his favourite clients. In the subsequent Graham Phillips case, where Mr Phillips was suing the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) for sanctions being imposed upon him without any legal case made against him, Swift actually met FCDO officials – one of the parties to the case – and discussed matters relating to it privately with them before giving judgment. He did not tell the defence he had done this. They found out, and Swift was forced to recuse himself.

Personally I am surprised Swift is not in jail, let alone still a High Court judge. But then what do I know of justice?

The Establishment politico-legal nexus was on even more flagrant display today. Presiding was Dame Victoria Sharp, whose brother Richard had arranged an £800,000 loan for then Prime Minister Boris Johnson and immediately been appointed Chairman of the BBC, (the UK’s state propaganda organ). Assisting her was Justice Jeremy Johnson, another former barrister representing MI6.

By an amazing coincidence, Justice Johnson had been brought in seamlessly to replace his fellow ex-MI6 hiree Justice Swift and find for the FCDO in the Graham Phillips case!

And here these two were now to judge Julian!

What a lovely, cosy club is the Establishment! How ordered and predictable! We must bow down in awe at its majesty and near divine operation. Or go to jail.

Well, Julian is in jail, and we stood ready for his final shot for an appeal. We all stood up and Dame Victoria took her place. In the murky permanent twilight of the courtroom, her face was illuminated from below by a comparatively bright light of a computer monitor. It gave her a grey, spectral appearance, and the texture and colour of her hair merged into the judicial wig seamlessly. She seems to hover over us as a disturbingly ethereal presence.

Her colleague, Justice Johnson, for some reason was positioned as far to her right as physically possible. When they wished to confer he had to get up and walk. The lighting arrangements did not appear to cater for his presence at all, and at times he merged into the wall behind him.

Dame Victoria opened by stating that the court had given Julian permission to attend in person or to follow on video, but he was too unwell to do either. After that disturbing news, Edward Fitzgerald KC rose to open the case for the defence to be allowed an appeal.

There is a crumpled magnificence about Mr Fitzgerald. He speaks with great authority and a moral certainty that compels belief. At the same time he appears so large and well-meaning, so absent of vanity or pretence, that it is like watching Paddington Bear in a legal gown. He is a walking caricature of Edward Fitzgerald. Barrister’s wigs have tight rolls of horsehair stuck to a mesh that stretches over the head. In Mr Fitzgerald’s case, the mesh has to be stretched so far to cover his enormous brain, that the rolls are pulled apart, and dot his head like hair curlers on a landlady.

Fitzgerald opened with a brief headline summary of what the defence would argue, in identifying legal errors by Judge Swift and Magistrate Baraitser, that meant an appeal was viable and should be heard.

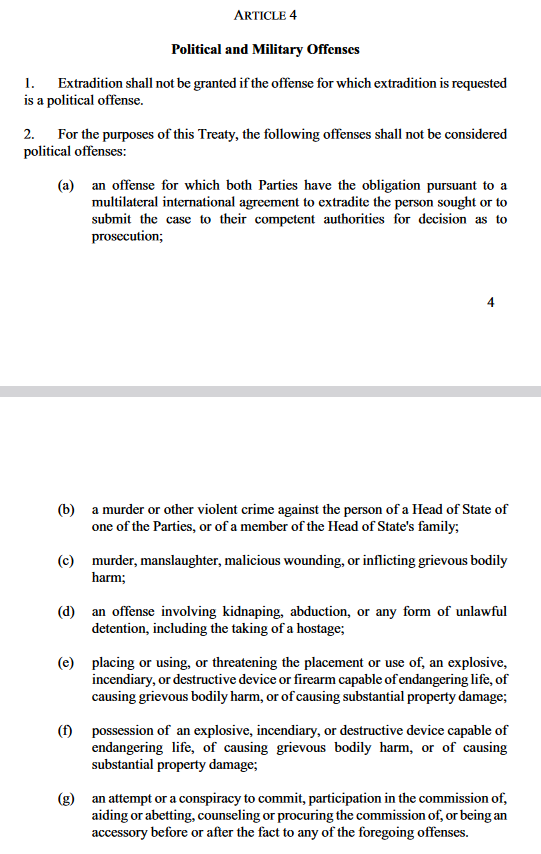

Firstly, extradition for a political offence was explicitly excluded under the UK/US Extradition Treaty which was the basis for the proposed extradition. The charge of espionage was a pure political offence, recognised as such by all legal authorities, and Wikileaks’ publications had been to a political end, and even resulted in political change, so were protected speech.

Baraitser and Swift were wrong to argue that the Extradition Treaty was not incorporated in UK domestic law and therefore “not justiciable”, because extradition against its terms engaged Article V of the European Convention on Human Rights on Abuse of Process and Article X on Freedom of Speech.

The Wikileaks revelations had revealed serious state illegality by the government of the United States, up to and including war crimes. It was therefore protected speech.

Article III and Article VII of the ECHR were also engaged because in 2010 Assange could not possibly have predicted a prosecution under the Espionage Act, as this had never been done before despite a long history in the USA of reporters publishing classified information in national security journalism. The “offence” was therefore unforeseeable. Assange was being “Prosecuted for engaging in the normal journalistic practice of obtaining and publishing classified information”.

The possible punishment in the United States was entirely disproportionate, with a total possible jail sentence of 175 years for those “offences” charged so far.

Assange faced discrimination on grounds of nationality, which would make extradition unlawful. US authorities had declared he would not be entitled to First Amendment protection in the United States because he is not a US citizen.

There was no guarantee further charges would not be brought more serious than those which had already been laid, in particular with regard to the Vault 7 publication of CIA secret technological spying techniques. In this regard, the United States had not provided assurances the death penalty could not be invoked.

The CIA had made plans to kidnap, drug and even to kill Mr Assange. This had been made plain by the testimony of Protected Witness 2 and confirmed by the extensive Yahoo News publication. Therefore Assange would be delivered to authorities who could not be trusted not to take extra-judicial action against him.

Finally, the Home Secretary had failed to take into account all these due factors in approving the extradition.

Fitzgerald then moved into the unfolding of each of these arguments, opening with the fact that the US/UK Extradition Treaty specifically excludes extradition for political offences, at Article IV.

Fitzgerald said that Espionage was the “quintessential” political offence, acknowledged as such in every textbook and precedent. The court did have jurisdiction over this point because ignoring the provisions of the treaty rendered the court liable to accusations of abuse of process. He noticed that neither Swift nor Baraitser had made any judgment on whether or not the offences charged were political, relying on the argument the treaty did not apply anyway.

But the entire extradition depended on the treaty. It was made under the treaty. “You cannot rely on the treaty, and then refute it”.

This point brought the first overt reaction from the judges, as they looked at each other to wordlessly communicate what they had made of it. It was a point of which they had felt the force.

Fitzgerald continued that when the 2003 Extradition Act, on which the Treaty depended, had been presented to Parliament, ministers had assured parliament that people would not be extradited for political offences. Baraitser and Swift had said that the 2003 Act had deliberately not had a clause forbidding extradition for political offences. Fitzgerald said you could not draw that inference from an absence. There was nothing in the text permitting extradition for political offences. It was silent on the point.

Nothing in the Act precluded the court from determining that an extradition contrary to the terms of the treaty under which the extradition was taking place, would be a breach of process. In the United States, there had been cases where extradition to the UK under the treaty had been prevented by the courts because of the ‘no political extradition’ clause. That must apply at both ends.

Of the UK’s 158 extradition treaties, 156 contained a ban on extradition for political offences. This was plainly systematic and entrenched policy. It could not be meaningless in all these treaties. Furthermore this was the opposite of a novel argument. There were a great many authoritative cases, stretching back centuries, in the UK, US, Ireland, Canada, Australia and many other countries in which no political extradition was firmly established jurisprudence. It could not suddenly be “not justiciable”.

It was not only justiciable, it had been very extensively adjudicated.

All of the offences charged were as “espionage” except for one. That “hacking” charge, of helping Chelsea Manning in receiving classified documents, even if it were true, was plainly a similar allegation of a form of espionage activity.

The indictment describes Wikileaks as a “non-state hostile intelligence agency”. That was plainly an accusation of espionage. This is self-evidently a politically motivated prosecution for a political offence.

[To be continued. Have to rush back into court. Sorry no proof reading yet]

By Karen Sharpe

Image by Alisdare Hickson, Creative Commons 4.0

On February 20 and 21, the High Court of Justice in London will conduct a hearing to decide whether WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange can appeal the court’s earlier decision to extradite him to the U.S. to face 17 charges under the Espionage Act and one for computer crime, with a Methuselan prison sentence of 175 years. This, even though Julian is not an American citizen (he’s Australian), and he was not under U.S. jurisdiction when the “crimes” were allegedly committed.

At the end of the two-day hearing the court could grant Julian permission to appeal, it could deny it, or it could postpone its decision to a later date. Or the two judges might have some other ruling up their puffy sleeves.

In the first instance, if permission to appeal is granted, whilst awaiting another hearing, Julian would most likely be returned to high-security Belmarsh Prison where he has been held for nearly five years under arbitrary detention in near-total solitary confinement, though he has been convicted of no crime. Belmarsh is known as Britain’s Guantanamo because of its torturous conditions as well as for its population of mostly alleged murderers and terrorists.

Julian, an award-winning journalist and publisher, a life-long promoter of peace, a nine-time nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize, is quite obviously not in that category, though there are those who think he is. Most notable among these is former CIA Director Mike Pompeo, who pronounced Julian “a darling of terrorist groups”, and defined WikiLeaks as a “nonstate, hostile intelligence service”.

The crime that Julian is essentially “guilty” of is revealing truths most uncomfortable to the ruling powers—practicing journalism as it should be practiced.

The second possible outcome of the upcoming hearing, denial of permission to appeal, could mean that within hours Julian would be shackled and placed on a U.S. military jet headed for Alexandria, Virginia. There his case will be heard by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, where many residents work in national security (CIA, FBI, Department of Defense) or have a family member who does. The jury pool comes from this group and, not surprisingly, no one brought before this court under the Espionage Act has ever been exonerated.

Not only would Julian be denied a fair trial there, according to experts such as Nils Melzer, former U.N. rapporteur on torture, but he would not be able to use the defense that what he did was in the public interest, though clearly it was. The outcome there for Julian has virtually been decided even though his final appeal in Britain has not yet been heard.

What happens to Julian after a near-certain conviction by the federal court is that he will forthwith be sent to Supermax ADX Florence Colorado—or a comparable hell hole—which was described by a former supervisor there as being worse than death.

Possible stay of the extradition

There is one intervention that could at the very least delay Julian’s rendition to the U.S. if his appeal is denied: Julian’s lawyers will petition the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to become involved as a last resort. Julian’s case certainly falls within the scope of Rule 39, under which the court takes on a case if “the applicant would otherwise face an imminent risk of irreparable damage”. This would be Julian’s case in the U.S. where he would be subject to inhuman and degrading treatment—torture.

But there are also a few complications: it is not certain that Britain would respect the court’s decision, and if extradition has already taken place, the U.S. may very well not honor a decision made by a European court.

If (the big if) the plane bearing Julian has not yet left the tarmac in Britain, and the ECtHR has taken on the case in time, it’s probable Julian would be returned to Belmarsh to await the subsequent ruling. Bail has previously been denied, even for health concerns, because Julian is considered a high flight risk, and it’s doubtful bail would be granted at this point.

It’s possible that the judges will not hand down a decision on February 21, but postpone it. A delay would avoid a messy outcry from the increasing numbers of fervent supporters of Julian during an important election year for both the U.S. and Britain, when a virtual death sentence of a publisher would not look good for an incumbent or any candidate who condones the extradition yet touts “a democratic society”.

In any case, barring instant extradition, nothing short of a deus ex machina could prevent Julian from being returned to Belmarsh to await his appeal, intervention by the ECtHR, or a delayed decision on the right to appeal from the High Court.

Deus ex machina?

As improbable as it might seem, the suggestion of a deus ex machina did recently come onto the scene in the guise of former president Donald Trump. Donald Trump, Jr., one of his father’s chief advisors, recently said that based on what he knows now, he would be in favor of dropping the charges against Julian Assange.

Vivek Ramaswamy, former candidate in the Republican party primary, now a Trump supporter who throughout his campaign said he would pardon Julian on day 1, stated that in a recent meeting with Trump, when they discussed various issues, Trump said he would be amenable to pardoning Julian. Three other presidential candidates also want to see Julian freed: Jill Stein, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and Marianne Williamson.

For a Trump pardon of Julian to happen, many factors would have to come into play here. Trump has previously flipflopped with regard to Julian, and may well do so again. “I love WikiLeaks!” he declared with great fervor in 2016, lauding WikiLeaks for having published internal emails of the Democratic National Committee showing it undermined Bernie Sanders’ chances of becoming the Democratic presidential nominee and instead installed Hillary Clinton.

But then Trump indicted Julian under the spurious 107-year-old Espionage Act and declined to pardon him during his last days in office. And, under Trump’s presidency, the CIA plotted to kill Julian. Perhaps now Trump wants to be seen as doing the right thing for Julian—or just gain the hundreds of thousands of votes of those who want to see that happen.

The possibility of Trump being elected and then pardoning Julian is of course very far from certain. If indeed it did happen, it couldn’t be before January 2025. By that time, unless extradited, Julian will have suffered yet another year in Belmarsh prison, where he has been held since April 11, 2019, on remand, at the bidding of the U.S.

Increasing demands for Julian to be freed

As Julian’s dire situation gathers more attention, voices from all around the world have risen up calling for his liberation. In a groundbreaking cross-party show of unity, members of Australia’s House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly (86 to 42) on February 14 for Julian not to be extradited but to be brought home. What was particularly significant here and welcomed by Julian’s supporters well beyond Australia is that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese also voted in favor, after months of waffling.

“Enough is enough”, he kept saying, yet not insisting that the U.S. pardon and release his country’s most famous citizen. This despite the fact that Julian’s return is what nearly 80 percent of Australians want. Perhaps Albanese’s previous inaction was motivated by a recently signed juicy agreement with the U.S. to buy nuclear submarines, bringing the country yet more into the orbit of the U.S. as a strategic satellite in a geopolitically important part of the world.

In view of Albanese’s reticence, a multi-partisan group of Australian parliamentarians has been consistently acting on behalf of those constituents who want Julian freed. Recently they uncovered a ruling by the U.K. Supreme Court that could be the cog in the drive to send Julian to the U.S. According to the law, if a government stipulates that a country to which a person is to be extradited from Britain has given assurances that that person’s health or life won’t be threatened in the receiving country, then those “assurances” must be thoroughly investigated by a third party before extradition can take place.

And so the parliamentarians have written to British Home Secretary James Cleverly calling for a probe into the risks to Julian’s health should he be extradited to the U.S.

In the U.S., House Resolution 934, introduced by Rep. Paul Gosar, a Republican from Arizona, calls for the U.S. to drop the charges against Julian Assange, stating that “regular journalistic activities, including the obtainment and publication of information, are protected under the First Amendment”. The Resolution has eight other co-sponsors from both parties and is currently before the House Judiciary Committee. While its passage there, then onto the floor of the Congress, then over to the Senate could be a lengthy route, its supporters hope that thousands of people will write to their representatives urging their support for this resolution, thereby bringing massive attention to Julian’s case and what it means.

Parliamentarians in France, where Julian also has a family, have called for Julian to be granted political asylum, though it’s questionable if this could be allowed if a demand for asylum has not been requested while the person is actually on French soil. Mexico and Bolivia have offered Julian asylum. Cities in dozens of countries have named Julian an Honorary Citizen.

The five major publications, The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, El Pais, and Der Spiegel, which had “partnered” with WikiLeaks in publishing thousands of files, signed an open letter on November 22 of last year calling for an end to the prosecution of Julian Assange They’re rather late to the game, even with that wishy-washy letter, having profited from enormous sales when the WikiLeaks files were released, then not only ignoring Julian, but criticizing him, often using lies and slander.

Julian’s importance has been acknowledged by hundreds of thousands of parliamentarians, human rights authorities, medical doctors, religious leaders (including the Pope), artists, teachers, trade unionists, legal professionals, journalists, students, writers all over the world who publicly demand his immediate release.

Nevertheless, the Americans and Brits may very well prevail, keeping Julian locked up for more years as he wastes away under the grueling prison conditions awaiting a final decision. Or they could prevail in having Julian sent to a supermax prison via the U.S. district court.

2 by 3 meters in Belmarsh

During the nearly five years Julian has been incarcerated in Belmarsh, he has been kept mostly in solitary confinement in a cell measuring 2 meters by 3 meters, for 23 hours a day, allowed to stretch his long legs in an enclosed concrete area for an hour. Food is budgeted at 2 British pounds ($2.50) a day per prisoner, with meals consisting of gruel, thin soup, and little else.

Julian has not seen sunlight since he entered the Ecuadorian embassy in London in 2012 seeking asylum there, apart from the day he was dragged from the embassy, or the days he was driven in a van from Belmarsh to those court hearings he was actually allowed to attend in person—albeit enclosed in a glass box (as is often the case in British courtrooms).

Not surprisingly his health has been consistently declining. Julian has lost a lot of weight and is paler than any human should be. In 2021, during or before a court hearing, (it’s unclear) he suffered a mini stroke at the age of just 49. He has subsequently been diagnosed with nerve damage and memory problems, and may very well suffer a much more serious stroke.

Death is never far away in Belmarsh—when Julian’s father John Shipton visited his son there, he reported that three suicides and one murder had occurred in the prison just during the past month alone. Nor was death far away in the embassy, where plain-clothes and uniformed officers menacingly patrolled and surveilled the embassy 24/7.

While Julian was considered paranoid for believing the U.S. wanted to kill him, an exhaustive investigation by Yahoo News in September of 2019 revealed that the U.S. and British intelligence services conspired to assassinate Julian by poisoning him while he was in the embassy or shooting him on the street or else kidnapping him from there.

Psychological torture

Julian’s mental health has also suffered severely, as would be the case for anyone incarcerated for so long in such horrifying conditions, undergoing repeated legal proceedings to determine whether the equivalent of a death sentence—lifelong internment in a U.S. supermax prison— will be imposed.

In a supermax prison, and especially under “special administrative measures” that would most likely be applied to Julian, he would be completely isolated. At least in Belmarsh he can now have some visitors, though restricted, and, finally, some books and writing paper. In the U.S. prison he would be in a virtually empty cell, forbidden any contact with the outside world, or even fellow prisoners, and thus denied any support or motivation to keep on living.

The toll on Julian’s mental health has been so significant that when Nils Melzer visited Julian in Belmarsh in May of 2019 with two medical experts, he stated unequivocally that Julian showed all the signs of psychological torture. His excellent book, The Trial of Julian Assange, lays out the case in great detail.

Judge Vanessa Baraitser, the magistrate who officiated during Julian’s first hearing, recognized Julian’s psychological fragility, as described in evidence presented to the court. Although she ruled in favor of extradition based on the 18 points presented by the American lawyers (obtaining, receiving, and disclosing classified information), she ruled against extradition on the grounds that she was certain Julian would commit suicide if placed in a supermax prison.

It’s unlikely Baraitser was motivated by the milk of human kindness, as she refused bail, saying Julian would “abscond”, and, ironically, had him sent back to the same place where, testimony showed, he had seriously contemplated and possibly even attempted suicide. Moreover, subsequent hearings and a final ruling on the 18 points for which she supported extradition would mean Julian would never be released from any prison.

It is clear to many that the process—the relentless persecution and prosecution of Julian—is the punishment. Keeping him silenced, in a deathly dungeon, unable to do what has always been his passion—revealing truths so that we may all act upon them to make the world a better place—is clearly an eroding and fatal punishment.

A threat to the real criminals

Why this ongoing punishment has been inflicted on Julian is to completely break him down, physically and psychologically, without even having to impose the very questionable ultimate blow of locking him up in a supermax prison for 175 years. The 10 million documents Julian published on WikiLeaks earned the wrath of those politicians, officials, plutocrats, dictators, rulers, generals, corporate executives whose murderous, illegal deeds he revealed, whether war crimes, crimes against humanity, corruption, mass surveillance. Ironically none of the perpetrators of those crimes has ever been convicted, while the publisher who revealed them remains in prison.

Revelations have helped end torture in Guantanamo, for example, overturn corrupt governments as in Egypt, end wars, for example in Iraq, aided by the very disturbing Collateral Murder video showing U.S. soldiers in Baghdad joyfully shooting down civilians from an Apache helicopter. Julian has done more than anyone to uncover how governments, politicians, corporations, the military, and the press truly operate. It’s not surprising they want him silenced forever.

The possibility of Julian’s cranking up WikiLeaks to once again be the propaganda and lies-shattering, truth-telling online publication that it was makes him a huge threat to all those all around the world who are committing unseen—or even seen—and with impunity the same and even more nefarious crimes Julian earlier revealed.

During Julian’s incarceration and WikiLeaks slowdown, alternative journalists and bloggers have done heroic jobs of reporting what must be brought to light—in Gaza, Ukraine, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, for example. But few, if any, has the capability to receive securely and completely anonymously major revelations from whistleblowers and then publish them for free for anyone anywhere in the world, as WikiLeaks did so successfully using a revolutionary method Julian invented and pioneered.

The two-day hearing beginning on February 20 will be the fourth time Julian’s case has been in court. The first time, under Judge Baraitser in the Magistrate’s court that denied extradition but upheld the Americans’ 18 points, was followed by a hearing before two judges of the High Court, ruling on the U.S. demand to appeal the extradition decision based on additional assurances. While highly unusual, if not illegal, to present new assurances at that point, the High Court nevertheless agreed to hear the appeal.

In December 2021 it overturned the denial of extradition, accepting the specious assurance by the U.S. that Julian would be treated well in a U.S. prison, unless, their worthless caveat stated, he did something to warrant changing that. Not only could such “assurances” be revoked, but they are unenforceable.

Assange’s lawyers then filed an application for a cross appeal to the High Court of the first court’s judgement as well as the Home Secretary’s decision to extradite. That application was denied by a single High Court judge.

Craig Murray (craigmurray.org), Kevin Gosztola (Guilty of Journalism: The Political Case against Julian Assange), and the excellent Consortium News have done thorough reporting on all these hearings, while the brilliant investigative reporter Stefania Maurizi has followed Julian and WikiLeaks from the beginning, uncovering, as in a detective novel, the government forces arrayed against Julian and their treacherous tactics (Secret Power: WikiLeaks and Its Enemies).

The right to an appeal will now be heard this February 20 and 21 by two High Court judges, Mr. Justice Johnson and Dame Victoria Sharp, who were recently announced. Sharp and her family have long and strong connections to Conservative party leaders, and Sharp’s recent ruling against a journalist, Carole Cadwalladr, in a libel case, was denounced by press freedom advocates for supporting the repression of public interest journalism. Previous judges ruling on Julian’s case have had equally questionable connections.

A case rife with illegalities

The illegalities in this case are numerous, as the bona fides of some of the judges suggest, and further underscore the fact that all along this case has not been about justice but politics. Among the many transgressions of justice and the rule of law figure initially the conditions under which Julian was kept in the Ecuadorian embassy, from which he could never step outside, even for a moment, even for urgent medical care, without risk of being whisked away and imprisoned.

He and his visitors, including his doctors and lawyers, had all their interactions with him filmed and ultimately sent to the CIA. Their electronic devices were confiscated during their visits, photographed, and that information was also sent to the CIA, thereby violating the rights of legal and medical confidentiality—to say nothing of the Fourth Amendment right to privacy—and potentially severely compromising Julian’s legal case.

Two lawyers and two journalists have filed a lawsuit against the CIA and Mike Pompeo plus UC Global, a Spanish security company that carried out the spying in the embassy, for these violations, and a federal judge in New York has agreed to let the suit go through, though any final decision will not be immediate.

An embassy’s premises are meant to be inviolable safe places for those seeking asylum there, yet British police, with the agreement of the Ecuadorian embassy under its newly elected government, dragged Julian—who is also an Ecuadorian citizen—from the embassy and locked him away in Belmarsh. They kept all his belongings, including his computers and legal notes. In Belmarsh he has been kept under conditions that violate any sense of human rights.

The original “crime” for which Julian was brought to prison was breaching bail when he went to the Ecuadorian embassy, rightfully fearing extradition from Sweden to the U.S. following subsequently dismissed—and fabricated—allegations of sexual assault in Sweden. Breach of bail in Britain carries a maximum penalty of a year’s incarceration, though in most cases it results in a fine or dismissal.

Yet Julian has been kept in Belmarsh well beyond that limit, never convicted of any crime, in clear violation of habeas corpus. Much of the irrefutable evidence presented by Julian’s lawyers—he did heavily redact documents before releasing them on WikiLeaks, not a single person was harmed because of the releases, Julian did not help Chelsea Manning leak classified documents—was indeed fallaciously refuted by the judges.

The Espionage Act, under which a journalist or publisher has heretofore never been prosecuted, was designed, as its name suggests, to prosecute those Americans working to undermine the U.S. war efforts by delivering national defense information to the enemy—espionage coming from espion, or spy, in French. Not only is Julian not an American citizen, and he was in Europe when he was publishing WikiLeaks, but the “enemy” to whom he was meant to have supplied classified information—information in the public interest—must ipso facto be any member of the general public anywhere in the world!

The U.S. First Amendment protects the publication of documents, even those that are classified. Moreover per extradition agreements between Britain and the U.S., a person convicted for political reasons—and the case against Julian is purely political—or who could face a death penalty in the receiving country, may not be extradited from Britain.

One of the most egregious transgressions of justice during Julian’s first hearing was the fact that the principal evidence against him was supplied by a diagnosed sociopath, Sigurdur Thordarson, who had been convicted of fraud, embezzlement, and crimes against minors, and who later recanted his testimony, saying he had been bribed by the U.S. to say what he did.

Though Julian’s defense in any impartial courtroom based on the rule of law would undeniably be upheld, he remains condemned, locked up, perhaps forever, with the uncertainty of his future a gnawing torture.

Groundswell of support

Thousands of people from all over the world plan to gather outside the Royal Courts of Justice where the hearing will be held on February 20 and 21 to support Julian, to demand that justice be done. As this is not a trial but a hearing to determine if an appeal against extradition can take place, it is unclear whether Julian will be present, though he has requested that he be allowed to be in court so he can confer with his lawyers. Though for most of his time in Belmarsh Julian was deprived of a computer—although he was once allowed one that had the keys glued—he has nevertheless played a major role in helping his lawyers prepare his legal case.

Stella Assange, Julian’s wife, mother of their two children, and one of his lawyers, has been travelling all over the world trying to convince world leaders, journalists, individuals why it’s in all of our interests that Julian be freed, that justice be upheld, that freedom of expression is sacrosanct, as is our right to know, and that governments must be held accountable.

There has been a groundswell of support for Julian as the court date approaches. Day X, as this date has been referred to in calls to action, has rallied even those who haven’t been active in Julian’s defense to protest in support of what may be Julian’s last attempt to be freed. From Boston to Buenos Aires, Sydney to Naples, Mexico to Hamburg, San Francisco to Montevideo, Denver to Paris, and well beyond, major demonstrations have been planned all across the world on February 20 and 21.

What’s at stake

What’s at stake for Julian is horrendous. What’s at stake for the rest of us is terrifying. If Julian is extradited and convicted under the draconian Espionage Act, the message will be that anyone anywhere in the world who says or writes anything that the U.S. considers against their interests can also be locked away forever.

While the U.S. seems to feel that extraterritorial jurisdiction is its right alone, other countries may decide to follow suit, picking off journalists or activists who don’t toe the government line. If a journalist and publisher is locked away forever for revealing truths, a clear message is broadcast, and even more journalists and publishers will self-censor, so the same fate isn’t rained down on them. And that ends a free and open press, that kills our right to know.

Today it is open season on journalists in many parts of the world, most egregiously in Palestine where some 120 journalists—and often their families as well—have been targeted and assassinated by the IDF of Israel. Increasing numbers of so-called news organizations unquestioningly publish government press releases essentially as news reports, to maintain access to those governments. Bloggers who write on Twitter or Facebook or other social media sites are frequently censored.

To understand what’s going on in the very complex world of today, we desperately need Julian Assange, with his analytical, erudite, prophetic mind, to reveal, assimilate, and interpret this precarious world so we might understand and act.

Some good news

The good news is that Julian has behind him his devoted family, travelling the world, speaking out for him. The excellent film “Ithaka” shows this in detail and very movingly. Julian also has behind him a dogged legal team of hundreds of lawyers and researchers looking for every possible way to secure his freedom.

And he has behind him the hundreds of dedicated supporters who hold weekly vigils whether in Piccadilly Circus or outside Belmarsh prison or in a square in Brussels or Berlin, or who join marches and rallies all over the world.

The other good news is that Julian is indefatigable. While incarcerated in the Ecuadorian embassy, under very difficult circumstances, during the last year often without Internet or telephone connections, Julian helped to publish 5 million documents, produced 3 books, launched more than 30 publications, and gave 100 talks. And he is extraordinarily resilient—few, if any of us, would be able to go through what Julian has, and to keep on going.

John Pilger, the brilliant journalist and filmmaker who recently passed away, said of his dear friend, whom he visited on several occasions in Belmarsh, “Julian is the embodiment of courage.” As Pilger was leaving the prison visitors room, he looked back at Julian. “He held his fist high and clenched, as he always does.”

No comments:

Post a Comment