Edvard Westermarck’s reasons for choosing Morocco

Finnish anthropologist and philosopher Edvard Westermarck (1862-1939), renowned for his work on ethics, (1) marriage and religion, devoted almost forty years of his life to the study of Morocco. Through successive visits between 1898 and 1926, he built up an exceptional ethnographic corpus on the religious practices, rituals and social structures of the Moroccan populations, particularly the Amazigh/Berber. (2)

Why did a European intellectual, trained in the positivist and evolutionist tradition, turn to Morocco? (3) (4) This geographical, cultural and methodological choice of field had several motivations: an intellectual quest, political accessibility to the country, and a personal fascination for a culture perceived as both archaic and alive.

Edward Westermarck is best known for his work on morality, marriage, (4) and incest, as well as for his fieldwork in Morocco, (6) particularly among the Imazighen/Berbers in the early 20th century. (7) He is considered one of the first ethnographers to conduct intensive field research in Morocco, at a time when anthropology was still highly theoretical and Eurocentric. He is, also, considered one of the pioneers of modern social anthropology. (8) He held professorships at the University of Helsinki and the London School of Economics. (9)

On the ethnographic work of Westermarck, Andrew Lyons wrote: (10)

‘’In 1893 Westermarck began his teaching career at Helsingfors (Helsinki), an association which lasted 25 years. He was to become Professor of Philosophy there in 1907. In 1898, Westermarck began fieldwork in Morocco. He was to make as many as 21 visits to the country over a 30-year period, spending a total of 7 years there. Much of his fieldwork was conducted in summers before and a few years after the Great War, but there were also protracted stays, including one continuous stay of two years and two months (1900-1902). Westermarck’s magnum opus, the two-volume, Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas, was published in 1906-1908. It reflected his command of written sources in anthropology, moral philosophy and psychology, but it also incorporated findings from his Moroccan fieldwork. By the time it appeared Westermarck was holding appointments in two universities in different countries, the London School of Economics (from 1904) and Helsingfors. In 1906, he was appointed Professor of Philosophy in Helsingfors, and in 1907 became Martin White Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics (LSE). Usually he would teach for two terms in Finland, teach for a term in London and then spend the summer in Morocco. His monograph, Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco, appeared in 1914.’’

He resided in Tangier for several years and was interested in Moroccan society, particularly its social structures, legal customs, popular religious beliefs, (11) and rituals. He is best known for his theory of early sexual aversion (now known as the Westermarck Effect). (12)

At a time when most anthropologists studied “from a distance”, Westermarck opted for direct immersion. Pre-colonial Morocco, rich in social, religious and legal diversity, offered him a unique terrain. He focused on rural populations, Amazigh/Berber tribes and dealt with popular religious practices.

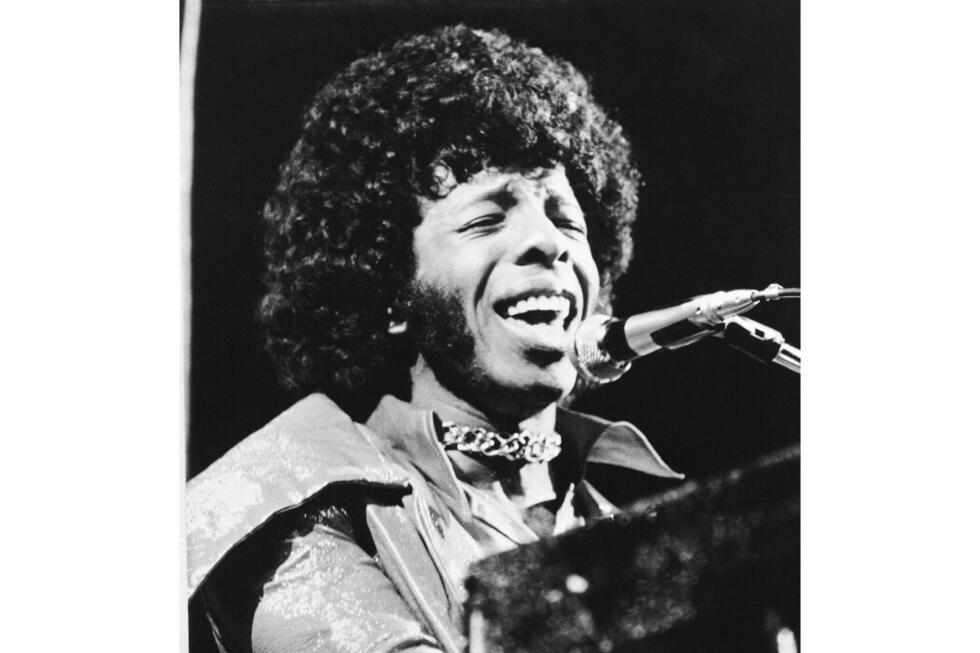

Edvard Westermarck (1862–1939). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

He began visiting Morocco regularly as early as 1898, mainly in Tangiers, where he established an observation base for around 30 years. At the time, Morocco was still an independent sultanate, but under colonial influence (French protectorate in 1912, and Spanish in the north). He was one of the first to observe Amazigh/Berber and Arab tribal societies from the interior, particularly in the Rif and High Atlas mountains.

Morocco enabled Westermarck to confront his philosophical theories (notably on the origins of morality and religion) with concrete social practices. He sought to observe societies where modern institutions had not yet “dissolved” popular beliefs: (13) “In Morocco religion is not a thing apart, a matter of Sunday observance or of occasional ritual. It pervades daily life, from birth to death, and manifests itself in countless acts and customs which are seldom questioned.”

For Westermarck, rural Morocco represented a “society in its raw state”, allowing to trace the original forms of religious thought, notably through witchcraft, prophylactic practices and the cult of saints. (14) His aim was to document the evolution of human thought from magic to religion, and then to rationality. In this, his approach remains marked by the dominant evolutionary paradigm of his time.(15)

At the end of the 19th century, Morocco remained an independent state, outside of the African colonial divide, but under increasing pressure from the European powers. This intermediate situation offered freer access to rural, less Islamized regions, without the cumbersome administrative constraints of the French or British colonies.

In relation to this, Westermarck points out: (16) “Morocco offered the double advantage of being little known and within easy reach of Europe. I went there time after time; and in the course of twenty-one journeys undertaken in the period between 1898 and 1926 I spent there altogether seven years.”

He was also one of the first Europeans to reside for long periods in certain Amazigh/Berber-speaking areas, notably in the Atlas Mountains and southern Morocco. His ability to live in contact with the local population, learn the language and forge ties opened up an exceptional terrain for the time.

Westermarck made no secret of his fascination with Amazigh culture, which he admired for its attachment to tradition, its customary legal system, and the richness of its popular beliefs. He is impressed by the social intelligence of collective practices: (17) “The Berbers, although generally illiterate, have a very elaborate customary law (ʿurf), administered by village assemblies (djema‘a), and many religious practices interwoven with magic and superstition.”

He also discussed hospitality and moral codes: (18) “Among the Berbers hospitality is a duty enforced by custom; a stranger is sacred, and to harm him is regarded as a crime of the gravest nature.”

But this admiration remains ambivalent: it is tinged with an exoticizing gaze, typical of colonial anthropology. As Talal Asad points out, (19) even “empathetic” anthropologists produce asymmetrical knowledge, rooted in a relationship of domination : “The fieldworker gains access to cultural and historical information about non-Western societies through a relationship of power. This relationship helps to define the conditions of research, and it determines in part the problems that can be formulated and the types of solutions that can be proposed.”

Nevertheless, Westermarck stands out for his willingness to describe without judging, and to question the internal logics of the rituals observed.

Morocco, for Westermarck, is at once an intellectual laboratory, an accessible space for observation, and a source of ethnographic wonder. His choice of terrain, far from being anodyne, responds to a vision of the world marked by the search for origins and cultural comparison. (20)

Why did Westermarck study the Imazighen of Morocco? A strategic, scientific, and cultural choice of terrain

At the end of the 19th century, Edvard Westermarck began a series of extended stays in Morocco, where he devoted himself to studying the religious, social, and legal practices of the Imazighen/Berbers, particularly in the mountainous regions of the High Atlas and southern Morocco. (21) This choice may seem surprising for a Finnish thinker trained in moral philosophy and European positivism. (22) So why this detour to the Maghreb? Why, of all the so-called “traditional” societies, did Westermarck specifically choose the Imazighen/Berbers of Morocco as the object of his observation and reflection? (23) We will see that this choice reflects three intertwined rationales: an intellectual quest, a historical opportunity, and a cultural fascination, all embedded in the colonial and scientific context of the turn of the 20th century.

Trained in philosophy and sociology, Westermarck sought to identify the foundations of universal moral beliefs and practices. According to him, rural societies, little influenced by urbanization or literate Islam, offered an ideal terrain for studying religion in its most “primitive” form: (24) “I wished to examine religious beliefs where they are still closely connected with everyday life and less formalized by theology.”

The Imazighen of Morocco, particularly those of the countryside and mountains, appeared to him to be conservative societies, where oral tradition and pre-Islamic rites survived. Their study allowed him, from his perspective, to access original forms of religious thought, essential to inform his work on morality and magic. (25)

Early 20th-century Morocco also represented a logistical and political opportunity. Even before the French Protectorate of 1912, the country attracted European researchers because it was still largely independent, yet sufficiently accessible for observation.

Westermarck took advantage of the political climate to travel freely throughout the Amazigh/Berber-speaking regions, sometimes on horseback, sometimes on foot, accompanied by local guides. He even settled in villages, participating in daily activities, which allowed him to observe practices rarely described before. (26) He says on this: (27) “Nowhere have I found a people among whom belief in magical practices is more alive and intimately bound up with daily life than among the Moroccans.”

His choice of Morocco was also part of the logic of accumulating ethnographic knowledge during the colonial era, when each empire sought to better understand the societies it administered or coveted.

Throughout his stays, Westermarck developed a genuine admiration for the social organization of the Amazigh, which he considered egalitarian, pragmatic, and based on community values: (28) “Although the Berbers are, for the most part, illiterate, their unwritten laws are remembered and observed with remarkable accuracy.”

He particularly admired the flexibility of customary justice, tribal cohesion, and local forms of spirituality. He noted the importance of marabouts, saints, (29) collective rituals, and prophylactic practices, all analyzed in terms of their social functions. This approach distinguished him from many contemporary Orientalists, who viewed these practices as purely “superstitious.” (30)

Main works from his Moroccan research

Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914, two volumes)

Published in 1914, Edvard Westermarck’s two-volume Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (31) is one of the first major ethnographic studies of matrimonial practices in Morocco, particularly among the Amazigh population. Far from being a simple folkloric description, Westermarck’s study is part of a rigorous anthropological approach, based on prolonged field observation and meticulous data collection.

Westermarck analyzed marriage as a social, religious and symbolic institution, closely linked to Amazigh community structures. His work, despite its descriptive richness, bears the marks of a European view of cultural otherness, and how it can be reread today in the light of postcolonial critiques. (32)

Westermarck’s interest in marriage is not limited to the union between two individuals. (33) He perceives this institution as a total ritual (in the sense that Mauss (34) would later theorize), engaging social, economic, symbolic and religious dimensions. He writes: (35) “A marriage among the Berbers is not simply a union of two persons; it is, above all, a contract between families, often entered into with a view to mutual advantage.”

Marriage ceremonies are long, sometimes spanning several days, and include:

Negotiations between families ;

- Purification rites ;

- Codified songs and dances ;

- Animal sacrifices to ward off the evil eye ; and

- Symbols of fertility and protection.

These elements show that marriage is an occasion for reinforcing social order, but also for ritual dialogue with invisible forces (djinns, (36) saints, spirits, etc.).

Westermarck pays particular attention to gendered roles in ceremonies, observing that women play a central role, particularly in singing, lamenting, preparing bodies and transmitting certain ritual knowledge: (37) “The women in the bride’s house prepare her with ceremonial songs and baths… These performances are not for display, but rooted in ancient customs believed to influence fertility and harmony.”

He also showed that marriage is less a personal choice than a negotiated social act, often at the service of tribal alliances, economic stability or the reproduction of a symbolic order. This places Amazigh practices within a collective logic, where the individual is inserted into a network of obligations and exchanges, sometimes far removed from Western representations of the romantic union.

Although Westermarck shows a sincere respect for Amazigh culture and a rigorous curiosity, his gaze remains marked by the evolutionary anthropology of his time. He saw in Amazigh matrimonial practices a trace of an earlier stage in human evolution: (38) “It is thus not improbable that many features of the marriage customs now prevalent among the Berbers may be survivals from a stage of culture in which institutions of family life were of a much simpler kind than they are at present.”

Such a reading tends to freeze Amazigh societies in an archaic past, positioning them as “others” in a shifted temporality. Talal Asad warns against this type of posture: (39) “The anthropologist, even when sympathetic, still writes from a position of power; the structure of his discipline ensures that he speaks with epistemological authority about the other.” Westermarck’s approach, though advanced for its time, thus participates in a colonial knowledge, which describes without really letting the local actors themselves speak.

Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco is a major work in the history of Moroccan anthropology and ethnography. Westermarck’s scope, precision and attention to detail have made it possible to document a ritual and symbolic richness little known in Europe. The work remains a valuable source for contemporary anthropologists, particularly in the study of Amazigh rituals, alliance systems and ritual performance. (40)

However, this work must also be reread with a critical eye, attentive to the theoretical frameworks of the time and the power relations implicit in any colonial ethnographic undertaking. The challenge today is to complement and reinterpret these archives through the words of the Amazigh communities themselves.

Ritual and Belief in Morocco (1926, two volumes)

Published in two volumes in 1926, Ritual and Belief in Morocco (41) is the culmination of more than twenty years of ethnographic observation by Edvard Westermarck among Moroccan populations, particularly the Amazigh/Berber. The author, already known for his work on morality and marriage, developed an ambitious ethnography focusing on magico-religious beliefs, saints, spirits, taboos and ritual practices. (42)

Westermarck sought to demonstrate that these practices – too often described as “superstitions” by colonial observers – are endowed with coherent internal logics, and that they reveal a rich and structured cosmology. (43)

The originality of Ritual and Belief in Morocco lies in the scope of the investigation carried out: Westermarck visited numerous rural regions of Morocco, particularly in the Middle and High Atlas, where he was able to observe practices that had not yet been described.

He explains his method as follows: (44) “In all this I have endeavoured not only to describe but to compare these beliefs with those of other peoples. And the material on which my descriptions are based has, with very few exceptions, been derived from the people themselves, either directly or through native informants.” The book covers a wide range of themes :

- Witchcraft (sihr), protection against the evil eye (‘ayn) ;

- The cult of saints (awliyâ’) and visit of shrines (ziyâra) ;

- Offerings, taboos, festivals and curses; and

- Invisible spirits (jnûn) and souls (rūḥ, âr).

By systematically cross-referencing Moroccan practices with other traditions (Finnish, Arab, Mediterranean), he adopted a comparative and evolutionary approach, aiming to place these rites within a universal history of beliefs. (45)

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Westermarck did not scorn popular beliefs. He insisted on their own rationality, often linked to social, psychological or symbolic needs. He writes : “Superstition, often despised by the educated classes, is in fact a serious attempt to explain the relation between cause and effect, and to enforce social norms by appeals to the sacred.”

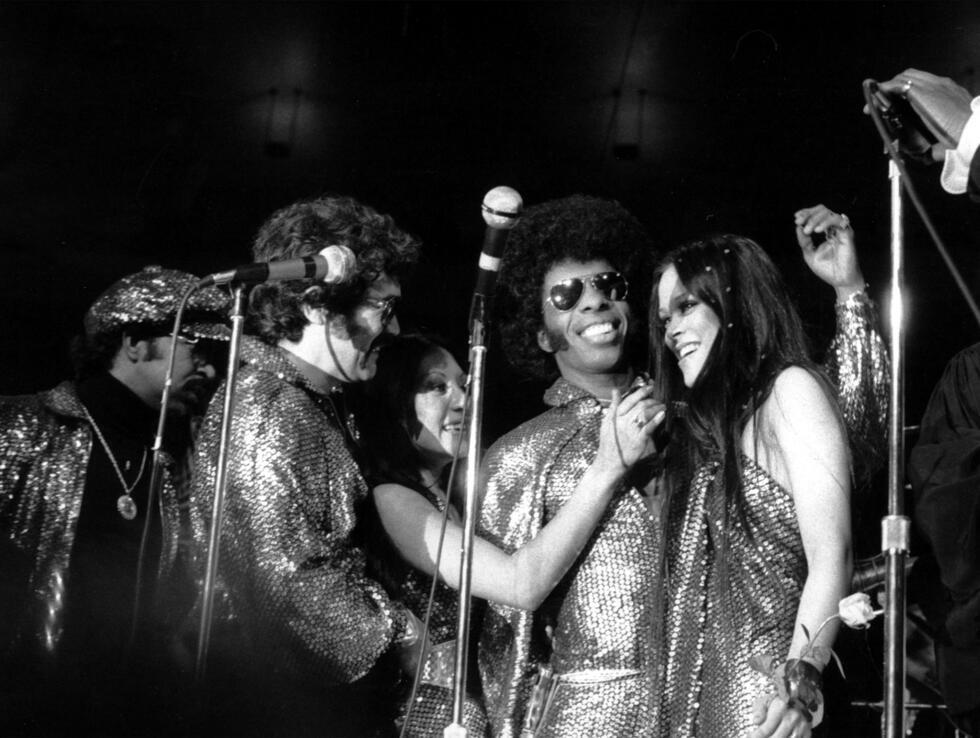

Berber wedding in Morocco. Photo Credit: Adil Chaouki, Wikimedia Commons

The cult of saints, for example, is seen as a social institution for channeling individual demands for healing, justice or fertility. Prophylactic practices (amulets, incense, holy water, sacrifices) aim to establish a boundary between the human world and invisible forces.

Westermarck described at length the ambivalent power of the jinn, capable of possession, hurt and disease: (47) “The jnûn are not necessarily evil, but they are dangerous because of their power and their susceptibility to offence. They may cause illness, madness, or misfortune when irritated, often unintentionally by humans.” These beliefs are analyzed as mechanisms for managing risk and explaining the inexplicable, integrated into everyday life. (48)

Ritual and Belief in Morocco is a monumental work, reflecting a deep respect for Moroccan folk cultures. Through his empirical approach, rigor and comparative sensibility, Westermarck has opened up an entire field of research into beliefs, saints, rituals and relations with the sacred in Morocco. But this work must be reread today with a critical eye, aware of the epistemological and political stakes of colonial ethnography. If Westermarck has made a major contribution to making known the richness of Amazigh culture, it is our duty as contemporary researchers to give a voice back to the communities themselves, and to value their own interpretations of ritual and the sacred. (49)

Wit and Wisdom in Morocco (1930)

In Wit and Wisdom in Morocco (1930), (50) Edvard Westermarck, in collaboration with linguist R. Brown, proposed an original approach to Amazigh and Moroccan culture through the study of proverbs. Unlike his previous works, which focused on religious rites (Ritual and Belief in Morocco, 1926) or marriage ceremonies (Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco, 1914), this book gives voice to popular wisdom itself. Drawing on a vast collection of sayings, Westermarck seeks to understand how Moroccans, and the Imazighen in particular, think, judge and structure the world. This essay analyzes the content and anthropological scope of this work, highlighting its contributions and limitations in the light of contemporary critical approaches.

Wit and Wisdom in Morocco brings together over 2,800 proverbs, mainly from Amazigh (translated from Tamazight) and dialectal Arabic oral traditions, collected in several regions of Morocco. This compilation is not purely literary; it is part of an anthropological project. (51) Westermarck says: (52) “The proverbs are of special interest because they throw light upon the moral ideas, customs, manners, and general outlook on life of the people who use them.’’ Through them, it is possible, according to him, to grasp the Amazigh “mentality”, particularly with regard to :

- Gender roles ;

- Hospitality and honor ;

- Power relations ; and

- Religious and supernatural beliefs.

For example, an Amazigh proverb translated and commented on in the book reads: (53) “A man without vengeance is like a goat without horns,” underlining the importance of honor and reciprocity in rural societies.

The study of proverbs enables Westermarck to develop a moral anthropology, i.e. an analysis of the implicit norms that govern society. (54) He notes, for example: (55) “Proverbs reveal that popular justice rests less on formal rules than on social equilibria sensitive to shame, prestige and reputation.”

This work goes beyond folklore. It enables us to draw up a mental map of traditional Amazigh values, which often escape conventional institutional or religious approaches. The proverbs about women, though sometimes tinged with misogyny, also show tensions about female power: (56) “She cries when she wants, and she laughs when she’s got what she wants.” Westermarck emphasized the pragmatic, ironic character of these maxims, which reflect a disillusioned yet lucid view of life.

Despite its originality, Westermarck’s approach is not free of bias. His position as a foreigner, collecting and translating proverbs into a language that is not his own, (57) raises questions of interpretation and fidelity. (58) What’s more, the selection of proverbs and their commentary sometimes reflect the prejudices of the time, particularly in judgments on male-female relations or supposedly “primitive” attitudes. (59)

Wit and Wisdom in Morocco remains a pioneering work in the history of Moroccan anthropology. By giving central importance to the proverbial speech of the Imazighen, Westermarck reveals a aspect of oral culture often overlooked by colonial researchers. This work contributed to bringing Amazigh orality into the scientific field and continues to fuel reflections on popular wisdom, everyday morality, and social structures in the Maghreb. (60) But this work must now be critically reread, taking into account the challenges of translation, power relations, and the need to allow the populations concerned to interpret their own culture.

Aspects of Berber culture in the work of Edward Westermarck

One of the central aspects of Westermarck’s work is his meticulous description of popular Amazigh/Berber beliefs. He highlighted a religious system marked by a strong imprint of maraboutic Islam, mixed with pre-Islamic elements. He devoted long sections to witchcraft (sihr), jnûn (spirits), talismans and local saints (awliyâ). According to him: (61) “In the Berber regions the official religion of Islam is mingled with a very ancient and deeply rooted belief in magic and spirits, which pervades the whole life of the people.” He further observed that the Berbers attribute supernatural powers to certain places, objects or individuals, which structures a large part of their daily lives.

In Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914), Westermarck provided an in-depth analysis of Berber marriage customs. He described various tribal practices: arranged marriages, wife exchanges (tabbâdl), dowries, divorce, polygamy and fertility rituals. He pays particular attention to the role of women and inter-tribal alliances. He wrote: (62) “Among the Berbers, marriage is less an individual affair than a communal one, intended to strengthen social ties and tribal cohesion.” He also pointed to the flexibility of Berber customary law (azref), sometimes in opposition to Islamic law, as evidence of a certain cultural autonomy.

Westermarck described Berber society as based on egalitarian tribal structures, often without a strong central authority. He admired what he calls their “primitive democracy”: (63) “The Berber political system, based on the assembly of free men (jama’a), represents a remarkable form of popular government.” He also noted the importance of blood ties (nasab), inter-clan alliances and vendetta rules, which ensure social regulation in the absence of a formal state.

Westermarck also devoted many pages to describing the daily activities of the Amazigh/Berbers: terraced farming, livestock breeding, trade, but also hospitality, gastronomy and clothing. He dwelt on seasonal cycles, agrarian festivals and craft techniques: Westermarck extensively discussed the seasonal rhythms and ecological integration of Berber economic practices. In Volume II, particularly in chapters concerning agricultural rites and seasonal festivals, he described how agricultural and pastoral activities among Berber communities are closely tied to seasonal cycles, including sowing, harvesting, and transhumance (seasonal migration of livestock). These practices are deeply embedded in their cultural and ritual life, illustrating a profound connection with their environment. This ethnography of everyday life gives his work an invaluable ethnological richness.

While Westermarck showed sincere desire to understand, his vision remained marked by the categories of his time. Some critics have noted a certain exoticism, notably in his focus on religious practices deemed “primitive”. Nevertheless, his detailed descriptions and immersion in the field make him a valuable observer, whose work still serves as a reference today.

In her book Impasse of the Angels: Scenes from a Moroccan Space of Memory, Pandolfo (64) delves into the complexities of ethnographic representation and the dynamics between the observer and the observed. She explores how ethnographers, including Westermarck, engage with their subjects, often oscillating between empathetic understanding and a sense of otherness. This duality reflects the broader challenges within anthropological studies of balancing closeness with critical distance.

Fundamental questions of Berber culture in the research of Edvard Westermarck

From his earliest works, Westermarck has been investigating Berber religious and magical beliefs. He wondered how these beliefs influenced their daily lives and social practices. He noted that Berbers firmly believe in the existence of jnûn, invisible spirits, as well as in the powers of local saints (marabouts). For him: (65) “In the Berber regions the official religion of Islam is mingled with a very ancient and deeply rooted belief in magic and spirits, which pervades the whole life of the people.”He posed a fundamental question: is folk religion simply a distortion of orthodox Islam, or an autonomous form of spirituality responding to specific social needs?

In Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914), Westermarck describes a wide variety of union forms, from arranged marriages to partner exchanges. He questioned the deeper meaning of these practices: are they primarily religious, economic or symbolic? He noted: (66) “Among the Berbers, marriage is less an individual affair than a communal one, intended to strengthen social ties and tribal cohesion.” The underlying question is the link between marriage and social organization. Westermarck saw it as a mechanism for alliance, conflict regulation and the reproduction of internal hierarchies.

Another of Westermarck’s major lines of research concerns the political organization of Berber societies. He was struck by the absence of authoritarianism and the presence of local institutions, such as the jama’a (assembly of notables). He wondered how a society could maintain itself and prosper without centralized power. He writes: (67) “The Berber community rests upon a self-regulating equilibrium, maintained by honor, negotiation, and a system of codified revenge.” His question is therefore anthropological and political: are so-called “primitive” structures viable alternatives to Western state models?

Westermarck is also interested in Berber justice. He noted that Berbers regulate their internal affairs according to customary law (azref), often on the bangs of Islamic law (established by the qudât). He noted: (68) “Customary law, though unwritten, constitutes a practical and flexible system of justice, adapted to the social needs and conditions of the community.”He thus posed an important question: how can an uncodified legal system ensure social cohesion, property protection and conflict resolution?

Finally, Westermarck explored the cultural dimensions visible in everyday practices: food, clothing, housing, agricultural work and festivals. He showed that Berber identity is expressed in ordinary gestures, but that they carry deep meaning: (69) “The life of the mountain Berbers is closely bound up with their environment; their economic activities, social organization, and customs are intimately connected with the land they inhabit.”

Is Berber culture stuck in tradition or capable of adapting to modernity? Edvard Westermarck’s work on the Berbers answered fundamental questions of an anthropological, political and legal nature. By examining popular religion, marriage, customary justice and tribal autonomy, he reveals the complex dynamics of a society that was little known at the time. His approach combined rigorous curiosity with a certain fascination, typical of nascent ethnology. Even today, his questions remain relevant to our understanding of the cultural logics of tribal societies

Westermarck: methodology and scientific approach in the study of Amazigh culture

Westermarck adopted an empirical method close to what would later be called participant observation, long before it became a pillar of modern anthropology. He spent a long time in Morocco, learned Moroccan dialectal Arabic, and lived among the local populations, particularly in the Berber-speaking regions: (70) “I made careful notes of every fact and every custom as it was told to me, verifying by repeated inquiries.” He emphasized the importance of cross-checking facts, avoiding speculative interpretations as much as possible. His close approach, without becoming an “insider,” allowed him to describe popular beliefs often overlooked by Moroccan scholars themselves.

One of the defining features of the Westermarckian approach is its systematic classification of cultural practices. The collected data are sorted according to themes—sacrifice, saints, witchcraft, the evil eye, spirits, etc.—and compared with facts observed elsewhere: (71) “In all this, I have attempted not only to describe, but to compare these beliefs with those of other primitive peoples.”

Westermarck thus followed a comparative evolutionary tradition, inspired by thinkers like Frazer. (72) He postulated a progression of human thought, going from the magical to the religious, and then to the rational. This approach, although criticized today, aimed to place Amazigh facts within a global history of religion. (73)

Westermarck’s methodology is not without limitations, particularly due to his evolutionary theoretical framework, which sometimes led him to describe Amazigh beliefs as “primitive superstitions” : (74) “These superstitions, irrational as they may seem, are powerful forces in the moral life of the Berbers.”

This hierarchical view has been challenged by postcolonial anthropologists such as Talal Asad, (75) who criticizes the claim of objective knowledge coming from a Western observer says that anthropological knowledge, like all knowledge, is implicated in historical relations of power, including colonialism.

Despite these biases, Westermarck’s work is distinguished by its thoroughness, its desire to reconstruct indigenous logics, and its exceptional documentary contribution. It still constitutes an essential empirical basis for studies on Amazigh culture, as Abdellah Hammoudi has acknowledged that despite Westermarck’s ideological framework, his ethnographic materials are essential for reconstructing the religious and symbolic order of Moroccan rural society.

Westermarck distinguished himself from his contemporaries by :

- Prolonged immersion in the environment studied, learning the language (Moroccan Arabic, some Amazigh).

- Empirical attention to detail: he took notes on local rites, beliefs, kinship rules and institutions.

- A positivist approach, influenced by Spencer’s sociology and the beginnings of British social anthropology.

- Participant observation (living among Moroccans, learning their language, attending rituals).

- Direct interviews with local informants.

- Empirical, comparative and positive approach (influenced by 19th-century European rationalism).

He was equally interested in the social, religious, psychological and legal aspects of daily life. However, he does not completely escape certain orientalist visions, albeit more nuanced than those of his colonial contemporaries.

Westermarck introduced a pioneering methodology in the study of Amazigh culture, based on direct observation, documentary rigor, and intercultural comparison. Despite the limitations of his theoretical framework, his work remains a major reference, not only for its content, but also for the method it pioneered: that of a field anthropology, patient and attentive to the details of local life. In the postcolonial era, his work deserves to be reread critically, but also recognized for its founding contribution to Moroccan anthropology.

Westermarck’s works on the Imazighen of Morocco: between pioneering ethnography and a European view of otherness

Westermarck’s work on the Imazighen is characterized by direct observation in the field, rigorous data collection and a desire to understand local practices from the inside. He adopted an approach that he himself described as “empirical”, concerned not to impose a Eurocentric explanatory grid.

In Ritual and Belief in Morocco, he devoted two entire volumes to popular beliefs, saints, spirits, the evil eye, sacrifices and rites of passage. He states: (78) “Among the Berbers, belief in spirits is not an abstract doctrine, but a living part of everyday life and experience.”

Similarly, in Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco, he described the multiple stages of betrothal, wedding, song and sacrifice, noting their ritual complexity and rootedness in the fabric of the community: (79) “Among the Berbers, marriage is less an individual affair than a communal one, intended to strengthen social ties and tribal cohesion.”

Despite the richness of his descriptions, Westermarck did not entirely escape the biases of his time. He often saw the Imazighen as living witnesses to humanity’s universal past, close to a “primitive” state that would enable us to understand the origin of human institutions. In Ritual and Belief in Morocco, he writes: (80) “The study of Berber beliefs and customs offers valuable insight into the earliest stages of religious development, revealing archaic forms of faith and ritual.”

Edvard Westermarck in Morocco on a white horse. Abdessalam el Bakkali to the left. (Åbo Akademi Picture Collections).

Thus, Westermarck’s enterprise, though humanistic in its method, is shot through with tensions between descriptive admiration and implicit hierarchization of cultures. Between fascination, scientific rigor and evolutionary bias, Westermarck remains an essential figure for anyone interested in Amazigh culture and the history of colonial ethnography.

Westermarck’s scientific contribution is indisputable. His works have served as a basis for several generations of Moroccan and foreign anthropologists. They continue to document practices that have disappeared or been transformed, such as certain Amazigh sacrificial rites, or daily relationships with saints.

He constituted an irreplaceable ethnographic archive. However, postcolonial readings insist on the need to recontextualize his approach, taking into account power relationships, the dynamics of cultural domination and the limits of an outsider’s view of local symbolic structures.

Westermarck’s work on the Imazighen of Morocco represents a major contribution to the history of anthropology. Through a rigorous fieldwork approach and a rare sensitivity to cultural complexity, he introduced Europe to an often marginalized society. Nevertheless, his work cannot be read today without a critical perspective, attentive to post-colonial dynamics and the epistemological challenges of representing the Other.

The nature of Westermarck’s work among the Imazighen/Berbers

His contribution was undoubtedly a pioneering ethnographic work conducted in a little-explored terrain at the time. He began his research in Morocco as early as 1898, even before the start of the French protectorate (1912). He was particularly interested in rural and tribal societies, notably Amazigh/Berber, in the Atlas and Rif regions, and around Tangier. At the time, very few European ethnographers observed these societies from the inside. He lived in Morocco for a long time (until 1936), learning Moroccan Arabic and living as close as possible to the local population. He adopted a field approach, now described as ethnographic, attending rituals, ceremonies, legal debates, weddings and so on. This method represents a break with the practice of anthropology (based in Europe on travelers’ accounts).

Westermarck observed that Amazigh/Berber tribes had their own legal rules azref, often independent of Islamic sharia law. He studied the role of the jama’a (assembly of notables), customary sanctions and methods of conflict resolution.

In Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914), he described in detail the practices of engagement, dowry, divorce and so on. He develops his famous theory of early sexual aversion (Westermarck effect), according to which children raised together develop a mutual sexual repulsion. (81)

In Ritual and Belief in Morocco (1926), he documented Berber beliefs related to marabouts, djinns, amulets, magic, baraka, etc. He was interested in a syncretic popular religiosity, distinct from orthodox Islam. (82)

Westermarck aimed to be objective and empirical: he collected, describeed, and classified. He believed strongly in the possibility of comparing societies according to general social laws (influence of 19th-century evolutionary sociology). (83) He didn’t limit himself to description : he looked for regularities, social and psychological causes. For example, he linked certain rituals to symbolic or social needs (cohesion, protection, transition, etc.).

But despite his good will, Westermarck remains a European writing about “the Other”, which leads to certain orientalist biases. His vision of Amazigh/Berber practices is sometimes exotic or hierarchical. Berbers are objects of study, rarely subjects of discourse.

The nature of Westermarck’s work among the Berbers is at once ethnographic, empirical and descriptive, and marks a major advance in knowledge of pre-colonial Moroccan societies. Today, however, his observations need to be contextualized and critically re-read, taking into account issues of power, representation and colonial legacy.

Westermarck’s scientific approach to Morocco

The history of anthropology is marked by pioneering figures who sought to understand human societies through new methods and unexplored terrain. Among them, the Finn Edvard Westermarck occupies a special place. Trained as a philosopher and anthropologist, he devoted almost forty years to the study of Moroccan societies, and Amazigh/Berber societies in particular, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. At a time when non-Western societies were still largely unknown or caricatured, he proposed an approach based on direct observation, comparative analysis and a positivist perspective inspired by the natural sciences. His works – notably Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914) and Ritual and Belief in Morocco (1926) – are still benchmarks in the field of Maghreb anthropology.

But what is the meaning of his “scientific approach” in a colonial context? In what way did Westermarck contribute to empirical knowledge of Moroccan societies, and to what extent should his method be critically re-read today? One must first look at how his work represents a major methodological breakthrough in the study of Morocco, before analyzing the theoretical principles underpinning his scientific approach, and then highlighting its limitations and the contemporary criticisms that stem from them.

Edvard Westermarck distinguished himself from the outset by choosing to carry out long-term fieldwork in a country as yet little explored by European anthropologists. (84) Between 1898 and 1936, he spent a great deal of time in Morocco, particularly in Tangier, but also in rural and tribal areas. He was particularly interested in the Berber populations, whom he saw as privileged witnesses of ancient social structures, relatively untouched by outside influences.

One of the major characteristics of Westermarck’s scientific work is its rootedness in direct, prolonged observation of the field. Unlike 19th-century anthropologists who studied “exotic” societies from European libraries, Westermarck opted for immersion: he stayed regularly in Morocco between 1898 and 1936, establishing a residence in Tangier and traveling to numerous regions, particularly Berber-speaking ones. (85)

He adopted an ethnographic approach, based on visiting local communities, attending their rituals and interviewing informants about their beliefs, legal norms and customs. He learned Moroccan dialect Arabic, which gave him access to popular narratives, although his knowledge of Berber remained limited.

This immersion gave rise to major works, notably Marriage Ceremonies in Morocco (1914) and Ritual and Belief in Morocco (1926), in which he offers meticulous descriptions of family life, religious rituals and customary law (azref). (86) His methodology is based on empirical description: he observed, noted and classified practices, seeking to understand the internal logic of the societies he studies. (87) In this, he is part of a prenarrative dynamic, attentive to facts before drawing generalizations.

Westermarck’s empirical rigor is accompanied by a theoretical and explanatory drive. Influenced by European positivism, notably that of Spencer and Mill, (88) he sought to uncover universal regularities in human behavior. He considered that cultural practices could be analyzed as objective social facts, subject to general laws. (89)

Thus, his study of marriage in Morocco led him to formulate the theory of the “Westermarck Effect”, according to which individuals brought up together develop a mutual sexual aversion, which would explain the universal taboo of incest. (90) He not only described the facts, but also sought to interpret them through a comparative and psychological grid, linking Moroccan customs to other societies studied in Europe and Asia.

Westermarck also integrated a moral and philosophical dimension into his approach. In The Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas (1906-1908), (91) he defends the idea that moral judgments are the fruit of social and emotional experience, and not of religious dogma. This conception led him to study local forms of justice, punishment or protection against evil (magic, djinns, talismans), interpreting them as rational responses to specific social contexts. (92)

First of all, its outlook remaind marked by a certain Eurocentrism: it analyzed Berber societies as examples of primitive stages of human evolution, in a sometimes hierarchical perspective. Certain practices are described as “irrational”, ‘superstitious’ or “archaic”, according to an implicit opposition between tradition and modernity, East and West.

Secondly, although he lived among Moroccans, their voices are absent from his writings. Informants are rarely identified, their words rarely quoted directly. Westermarck does not problematize his position as a foreign observer, nor the effects of his presence on the communities. He applied an exogenous analytical grid, without fully integrating local interpretative frameworks.