First published at Phenomenal World.

On the 3rd of January 2026, Washington launched a military assault on Caracas, capturing Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. In gross violation of the UN Charter, one hundred and fifty US aircraft bombed essential infrastructure throughout Northern Venezuela as the military raided Maduro’s compound.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the intervention was just how smoothly it went. In its aftermath, former Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez swiftly took the stage and embarked on a historic overhaul of the country’s Organic Hydrocarbons Law, paving the way for the privatization of its vast oil industry.

What explains Maduro’s downfall and what does it signal for the rest of Latin America? Phenomenal World editors Maya Adereth and Camilo Garzón discussed these questions with Venezuela’s former Energy Minister, Rafael Ramírez. As Chavez’s longest-serving cabinet member and President of Venezuela’s national oil company, PVDSA, Ramírez presided over the country’s developmental victories and rising global influence. Under Maduro he served as Permanent Representative to the UN before resigning from his post amid disagreements with the government. Here he reflects on the trajectory of Venezuela’s resource economy, its changing geopolitical orientation, and the future of the Bolivarian cause.

Maya Adereth: Let’s begin with your entry into the Venezuelan energy ministry. What were your strategic priorities when you joined Hugo Chávez’s government in 2000, and how did you cope with the dramatic oil sector strikes of 2002-2003?

When I became President of Venezuela’s National Gas Entity (ENAGAS), the question of oil was generating profound internal conflict. PVDSA, Venezuela’s oil company, was at that time pursuing the “apertura petrolera” — a policy in which the best oil areas were handed to private and largely American companies. Leaders of PVDSA had hoped that new legislation would legalize those contracts.

Of course, we did not pursue this path. As a result, violent conflict rapidly broke out, culminating in the attempted coup d’état of April 2002. My main objective as President of ENAGAS was to prevent Venezuelan gas from being privatized, handed over to US companies like Enron, and extracted from the country. This was critical not only because there was no technical reason to privatize the sector, but also because that gas was essential for our own energy and economic infrastructure.

One of the first things President Chávez did in response to the attempted coup was to change the key ministries. I was appointed oil minister in July 2002 with two core aims: bring the oil industry — then in open defiance — under control, and implement the newly enacted Hydrocarbon Law, which reserved oil extraction to the state.

In response to these policies, the 2002 oil strike paralyzed production with the demand that Chávez leave the country and resign. As minister, it fell to me to reestablish control of the PDVSA company and oil production. In January 2003, we were producing 23,000 barrels of oil per day. In March of that same year, we increased production to 3 million barrels, becoming the fourth largest oil exporter in the world. We managed to stabilize our production and sustain it until Nicolás Maduro came to power.

It must be said that the strike was not an act of sabotage by the workers. The workers were with us the whole time. It was sabotage by senior management, who facilitated a naval blockade of our coasts and halted production. This was a traumatic moment in which we lost 20,000 workers. With the 20,000 who stayed, we managed to revive production and recover full operational capacity. That was my baptism by fire in the oil industry and in government.

Camilo Garzon: What role did companies such as ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips play in the political disputes of the period? What happened to these companies after you left the ministry during the Maduro era?

Immediately after we gained control of PDVSA, which was the main obstacle to the Hydrocarbons Law, we began to redevelop a legal framework for the sector. The first thing we did was to shift from operating agreements to joint ventures. Operating agreements were a mechanism through which previous administrations had handed over the management of oil production to the private sector. We reversed that, and invited them to create joint ventures with PDVSA instead.

In 2006, we proposed to the large international companies, namely ConocoPhillips, Exxon, Chevron, Total, Equinox, Eni, and Repsol, that they embrace the new law. We got 31 of the 33 international companies to agree, and a nationalization decree signed by Chávez was issued. Overall, this was a successful process that ensured most companies would migrate to the new scheme and we could retain them as partners.

ConocoPhillips and Exxon, however, did not accept our terms. They were unwilling to work under Venezuelan law, despite the advantages of the proposals. We took control of their areas, and they resorted to international arbitration courts. ExxonMobil sued Venezuela for $16 billion before the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in Paris. We went, defended ourselves, and won, and the ICC said we only had to pay $907 million. Then they sued again for $10 billion, this time before the Tribunal of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in Washington. We defended ourselves again and won once more, ultimately paying $1.6 billion minus the $900 million already paid.

One year after I left the ministry in 2014, ConocoPhillips also sued Venezuela before the ICC. That time, the Maduro government did not defend the cases adequately. We lost as a result and the ICC ordered Venezuela to pay $2 billion. Then Conoco sued us again before the ICSID, and once more we were charged with paying $8.3 billion total. Of that money, the Maduro government paid nothing to ConocoPhillips and left much of the debt to Exxon unpaid.

From then on, the companies began to file claims abroad. ConocoPhillips succeeded in getting a Delaware court to confiscate the assets of Citgo, a refinery we had in the United States, which was valued at $14 billion in 2014 and ended up being seized. It would have been enough to pay the companies what we owed them, but now it is being auctioned off for $5 billion to the United States.

MA: In 2000, OPEC leaders came together for the first time since 1975 and relaunched the organization with the aim of advancing a shared political vision. In 2016, OPEC+ emerged — a more politically powerful organization, but with a looser political purpose. What has been Venezuela’s position within OPEC’s internal debates?

The Caracas summit in 2000 was a very important meeting, during which Chávez took over as OPEC leader and managed to convene the member states despite the recent invasion of Kuwait by Iraq and the war between Iraq and Iran. There were two important groups within OPEC at the time. One consisted of the Gulf monarchies, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar, which were more aligned with the United States. The other consisted of countries like Venezuela, Iran, Algeria, and Libya, which were more forceful about defending geopolitical and resource sovereignty. With a renewed production rate of 3 million barrels, Venezuela gained an important position in the organization’s political decisions.

The Venezuelan government had already advocated for the creation of a broader OPEC that would include Russia, but at the time, Saudi Arabia opposed this for fear of losing its relative strength. When Chávez died, Maduro neglected the organization and Venezuela’s domestic oil production, which fell to 1.9 million barrels in 2017. From this point on, Venezuela’s oil production would continue to fall, compounded by the impact of US sanctions. From the fourth largest oil producing country in the world, we plummeted to number 18.

The loss of political influence in OPEC was inevitable. With the military intervention in Libya, a weakened Venezuela, and sanctions on Iran, the Saudi monarchy no longer feared Russia’s participation in the broader OPEC framework. Russia’s invitation to OPEC+ remains a great initiative, however, because someone still has to defend oil prices. It is very telling that when Covid-19 caused oil prices to plummet worldwide, it was Donald Trump himself who called on OPEC to cut oil production and protect prices. This alone confirms the importance of the organization.

MA: PDVSA opened its first office in China in 2005. Today, China’s National Petroleum Corporation has producing assets in Venezuela, and there have been recent reports that Trump’s intervention has caused problems for Venezuela in servicing its debt to China. How has Venezuela’s relationship with China evolved and what stakes does China have in the current crisis?

For a hundred years, Venezuela was a satellite of the US economy. All our oil production was sold to the United States, and it was sold at discounts of up to 40 percent—$4 per barrel when the price was $11. We were an oil enclave for US transnational corporations.

When the Chávez government stabilized the industry, it sought to diversify oil supplies. It began within the region itself, with the creation of Petrocaribe in 2005, a cooperation agreement among the poor island countries. Chávez then pursued an agreement with Argentina and later expanded to the European market, where we made agreements with Portugal, Spain, Italy, and France. During that process of expansion, we formed relations with China with the idea of helping to build a multipolar world. In 2005, Venezuela was not selling a single barrel of oil to China, so these relations were absolutely fresh.

Opening up to China involved logistical changes, such as finding tankers with a capacity of 2 million barrels and formally inviting Chinese companies to produce Venezuelan oil. Chinese companies had access to areas that allowed them to produce up to 1 million barrels of oil per day. When I left the ministry in 2014, Venezuela was selling 600 barrels of oil a day to China directly to the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC). This was out of 2.5 million total exports—24 percent of total production. The great advantage of the arrangement was that, unlike our agreements with the United States, all payments from China were at market price. Yet throughout this period, we continued to send 1.2 million barrels, almost half of our exports, to the US.

The relationship with China also opened up other areas of cooperation. The Joint China-Venezuela Fund of 2007 offered domestic financing payable in oil. Another part of the agreement included the supply of technology and equipment. Including India, to whom we supplied 400,000 barrels, we had a market of 1 million barrels in Asia with two of the world’s largest oil importers. This was a win-win relationship.

When Maduro came to power, these plans and programs fell apart. Petrocaribe collapsed, and oil was no longer supplied through this alliance. The agreement with Argentina was blocked after right-wing President Mauricio Macri took office. The supply agreements with India were no longer fulfilled, nor were those with Europe. And with China, supplies were greatly reduced. Maduro also incurred enormous debt with China, estimated at up to $70 billion in loans, though official figures are unavailable. Our commercial relationship with China has therefore weakened significantly.

CG: What did Maduro’s intervention in PDVSA consist of, and what effects did it have on the country’s oil production? What are the main differences between Chavismo and Madurismo when it comes to the management of the oil industry?

Maduro sought direct control of all the country’s institutions. He started with the economy, taking control of the Ministry of Finance, the central bank, and, of course, PDVSA, where he appointed people loyal to him. I opposed that, and that is why they pushed me out of the country.

The government then began to imprison workers from the organization. More than 150 managers and directors were sent to prison, many of whom have been there for more than eight years. Former oil minister Nelson Martínez died there. It was undoubtedly a violent intervention, crowned by the appointment of a general from the National Guard, Manuel José Quevedo. Quevedo took charge of PDVSA and persecuted more than 30,000 employees in the industry.

So, the first thing that was lost as a result of the new government was human capacity. Maduro’s administration made the mistake of trying to control the company’s operating budget, something Chávez never did. This left the company without any money, and PDVSA came to a standstill. From a production of 3 million barrels in 2013, we fell to 500,000 in 2020, and today it stands at 965,000.

Since Maduro rose to power, we have lost almost 75 percent of our oil production capacity. That had never happened in any oil-producing country in the world, unless it was involved in an internal war. But in Venezuela, what happened was an internal war by the government against the oil industry. Much of the current production is sustained by Chevron, which pays no royalties or taxes.

In an oil-producing country with a rentier model imposed by transnational corporations, the collapse of the oil industry often means the collapse of the country itself. The Venezuelan economy contracted by 80 percent. The minimum wage fell from $450 per month to $2 per month. And 8 million people left the country because it became impossible to live there.

The fundamental difference between Chávez and Maduro is that the former leveraged oil in service of the population. Maduro, on the other hand, privatized oil and placed it in the hands of his political operators. All our social programs were dismantled. We went from a country that had a national developmental and redistributive project to one that was decimated, internationally isolated, without institutional legitimacy, and lacking strategic leverage.

MA: During the 1950s, Venezuela was the largest destination for US foreign investments and one of its largest sources of revenue. Is Trump trying to restore the 1950s model, and if so, should we understand this as pure resource control, price-setting control, or something else?

The first thing to say is that any military intervention in Venezuela must be firmly opposed. The capital city, Caracas, was bombed for the first time since we became a republic. The new US national security policy talks about reviving the Monroe Doctrine. This is a clear regression by the United States to the 1950s: the time when Latin America was dominated by military dictatorships in the context of the Cold War. Today it is Venezuela. Tomorrow it could be Colombia. After that it could be Mexico, or any other country.

Trump’s attempt to control the oil industry is especially concerning for Venezuela, because we would return to the concession period. Transnational corporations began to exploit oil in the country from 1920 until 1976, when it was nationalized. During those years, the United States did whatever it wanted with Venezuela. It took more than 50 billion barrels of oil without paying royalties or taxes. That changed with the nationalization of oil and, later, with Chávez, the nationalization of the oil belts of Orinoco.

The US claim — which the interim government has allowed — that profits from Venezuelan oil exports should go to a fund managed by the US Secretary of State, is an intervention that has not happened in any country since World War II. It has no political or legal basis. This will not be sustainable over time, but in order to resist it effectively Venezuela must have the capacity to increase production.

CG: Venezuelan oil production is already committed to domestic consumption and bilateral contracts primarily with China, Iran, Russia, and Cuba. What are the prospects now for fulfilling these contracts under US supervision, and how is OPEC’s role being reconfigured in light of this new situation?

If the United States were to control oil production in Venezuela, OPEC would be hugely weakened because of the model it represents for producing countries. The nationalization of oil in Venezuela had an international significance — it represented a vindication for all oil-producing countries who, thanks to their control over production and exports, were able to implement OPEC policies. If a country as important as Venezuela backs down from this model, any other country could follow in the face of a military confrontation: Libya, Iraq, or Iran. This would be disastrous for OPEC.

A number of US transnational companies have already told the White House that they will not return to Venezuela. Companies have to respond to their direct bonds and make decisions that make practical sense. So it will not be easy for Trump to get companies to invest in Venezuela as he wants. The current oil market is marked by abundant production, and there are many opportunities for Exxon and Chevron to seize, Guyana being just one example. There, the companies have guaranteed production of 1 million barrels of oil by 2027, with only 1 percent royalties. They are not desperately looking for oil fields.

But, in any case, Venezuela remains very important due to the simple fact that we can certify the largest oil reserves on the planet. The United States has about 32 billion barrels in reserves, which at the current rate of consumption will last for seven or eight years. This is a strategic problem for them, especially since they have discarded the energy substitution policies of the Biden agenda. They need oil.

Venezuela’s current production agreements are with China and Russia, each of which could produce up to 1 million barrels. But since Chávez’s death they have halted their investments. The Chinese only produce 100,000 barrels through the joint venture of Petrosinovensa. They could produce 1 million, but they did not invest under Maduro. The details of the other agreements with Iran and Cuba, which are not for production but for supply, are secret. Obviously, the United States is seeking to undermine these agreements so that oil no longer reaches Cuba.

Russia and China have said, albeit very timidly, that their projects in the country are still legally in force. But I think everyone is waiting and probably negotiating with the Americans. Neither Russia nor China is going to go to war to maintain their production in Venezuela, which is already at very low levels.

CG: What do you think should be the guidelines for a plan to rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry? What efforts are necessary to ensure that its profits can be used for economic reconstruction rather than being syphoned out of the country?

The problem we face with oil is not a technical one, it is a political one. In Venezuela, we need a return to the rule of law and to some degree of normality. Only then will our oil industry be able to undergo some kind of reconstruction, because the damage done to it has been very great. We must release all political prisoners, call back all the managers and workers who left the company out of fear, and make a national agreement to rebuild oil production. We need to create the political and economic conditions, within the boundaries of a sovereign and unified nation, that will allow us to focus on this issue.

The Orinoco oil belt is the country’s newest large oil-producing area. The capacity is there but it is currently unexploited. This area should be prioritized and its oil dividends should be used to meet human needs, flowing into wages and food; and then we can move on to the most problematic and oldest areas, such as Lake Maracaibo. Trump, of course, wants to seize the monetary gains from Venezuelan oil. But even before his intervention, Maduro’s allies were reselling oil to a ghost fleet of buyers who received it at a 25 percent discount and paid for it in cryptocurrency. Oil must be sold again at market prices and that money must go to the Central Bank of Venezuela so that it can be injected into the national economy, as the law requires.

A government of national unity is necessary to enshrine the reconstruction of the oil industry as a national priority. Then the political battle can be fought over what we should do with these revenues, whether they should go to the national bourgeoisie or to the people. But this conversation can only take place once we have rescued the management of oil.

Although Venezuela is an oil-producing country, it does not actually depend on domestic oil consumption. Almost all of its energy comes from water sources. But in the short and medium term, at the global level, there is no technology or energy source capable of replacing oil. The best proof of this was when Covid shut down the economy of the developed world. When they tried to restart it, wind energy and electric cars did not come to the rescue. What countries asked for was oil, and more of it than before. This indicates that oil, and Venezuela, will continue to play an important role in global energy demand.

The essential transition for Venezuela will be out of the oil rentier model. We made a great effort in that regard during the last year of President Chávez’s life and prepared something called the Plan de la Patria, with the help of the China Development Bank. When Chávez died this all came to a standstill. But that is a task that new generations of Venezuelans from now into the future will have to complete.

30 Days in Venezuela

Brian Mier

March 6, 2026

On January 23rd, I ignored a factually incorrect State Department warning about chavista motorcycle gangs “kidnapping Americans” and flew into the airport in La Guaira, Venezuela, for a 30-day reporting assignment for TeleSur. The first thing I saw stepping into the airport was a “wanted” sign for US-backed 2024 presidential candidate Edmundo Gonzalez, who fled the country that September after being charged with falsification of public documents, instigation to disobey the law, conspiracy and other crimes associated with the wave of violent mercenary attacks against police and public institutions the day after the elections on August 1.

I encountered motorcycle clubs several times at Free Maduro rallies, and contrary to the State Department Warning, no one kidnapped me.

I was a little worried. I remembered my trip to Serbia a few years earlier when friends from the Party of the Radical Left showed me the burnt out shell of the Radio-Television Serbia headquarters, which was bombed by US/NATO forces in 1999, killing 16 people, including actors, journalists and an employee in the makeup department. With Iran’s public TV station bombed by Israel in 2025, I was reminded that the US police-state has no moral qualms about the murder of journalists.

The US and freedom of the press: Radio-Television Serbia headquarters in April, 1999.

Luckily for the people of Venezuela, however, things had now returned nearly to normal after the January 3 attack.

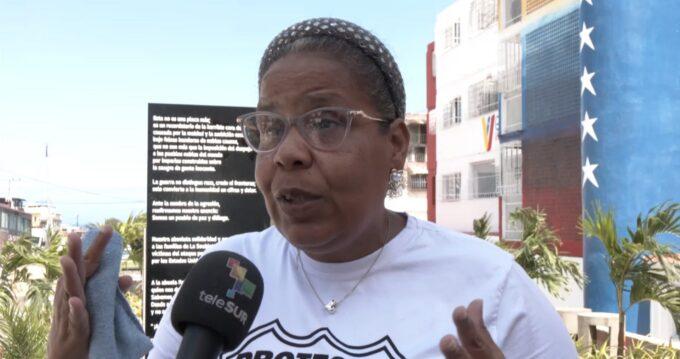

My first assignment was in Carlos Soulblette, a working class neighborhood adjacent to a naval academy in La Guaira which had been hit with US missiles. We watched repairs underway in one of the hundreds of thousands of ownership-based social housing buildings constructed by the Maduro administration, which had been directly hit, killing Rosa Elena Gonzales de Yanez, an 82 year old grandmother. I interviewed a middle aged woman named Maria Elena Carreno, the next door neighbor of the woman who had been murdered by the US government.

“When we managed to get out to the living room,” she said, “we saw that the door was gone. The wooden door had been completely blown away by the force, by the sound. I told my husband ‘Let’s calmly open the gate,’ because we didn’t know what could be waiting for us, since everything was full of dust. Thank God that we stepped out cautiously because we realized the wall was no longer there. If we had run out of the living room we would have plunged into the void.”

Maria Elena Carreno, nurse and next door neighbor of victim of US missile strike.

Two days later, I covered the first of 6 “free Maduro” protests I would report on during my month in Venezuela. Thousands of local residents had gathered in a favela in Antimano parish to march down to a main avenue and close it off, demanding the return of their President and First Lady.

A local resident named Ronny Camelo, told me, “Since the empire burst into the dreams of the Venezuelan people on January 3rd, crossing our border and violating all international laws, we demand that the will of the people is honored. We demand the return of our First Lady and our president Nicolas Maduro Moro, who was elected by the power of the people and the social movements. We pledge all of our support to comrade Delcy Rodríguez to bring back our president Nicolás Maduro Moro. Viva Independence and Viva our socialist homeland!”

Another positive thing I noticed in Caracas was the near absence of homeless people. During my month of traveling to the four corners of the city during news reporting and on my days off, I counted a total of 5 homeless people in a city of 3 million. As in any city, there were signs of poverty, but in terms of homelessness I can’t remember visiting any city in my home country of Brazil, the US or the UK in the last decade that had so few homeless people. This is undoubtably due in part to the Bolivarian government’s social housing program, which has seen construction of over 5 million social housing units in the last 15 years, in a country with a total population of 28 million.

Unlike the average month in Recife, where I live, there were no electrical blackouts while I was there. I commuted to Telesur by subway and bus. Although the subway operating speed was as slow as it is in US cities like Chicago and New York, they came every few minutes, even on Sundays, and at 17 cents US, the ticket price was a bargain compared to the $1 USD I am used to paying in Sao Paulo. The buses are old and raggedy looking, but they are run by cooperatives instead of outsourced private companies like in Brazil, and are dependable, especially with that 17 cent fare price.

I found grocery prices to be significantly higher than in Brazil, but the residents of poor and working class neighborhoods buy much of their weekly groceries at the government neighborhood markets which sell basic food stables at heavily subsidized prices for residents. Although I didn’t need this service, I understand that there is still a big problem with medical treatment in Venezuela, as after the Trump administrations criminal blockades kicked in and the national income plummeted by 90% between 2017 and 2020, there was an exodus of doctors out of the country, leaving many of the public health posts in working class neighborhoods woefully understaffed. In January, acting President Rodriguez announced plans to implement a new, universal public health system. Hopefully the increased oil revenue caused by relaxing the blockades can help transform this into a reality.

Subsidized prices at weekly market in San Augustin.

Caracas is still crippled by lack of parts for its water system caused by the US blockade and we went for 24 hours without water in our apartment one day, forcing us to take bucket showers with water from our reserve tanks. An end to the blockades would quickly solve this problem. When Hugo Chavez took office in 1999, Venezuela imported 80% of its food. Over the last 26 years, the nation has developed food sovereignty, with a record 94% produced nationally in 2025. The minimum wage, including the mandatory minimum bonus system established by the Maduro administration, hovers at around $160/month, compared to around $300 in neighboring Brazil. This is a weak point in the system that I heard many people grumbling about, which hopefully will improve as the economy continues to grow. With 19 consecutive quarters of positive GDP growth, the time seems right for revamping the minimum wage policy. When Lula first took office in 2003, Brazil’s minimum wage was under USD$50, and his 8 consecutive above inflation minimum wage increases are now cited as the most important factor in poverty reduction. This serves as a good example for the Rodriguez administration.

On February 2, while sitting in the journalist’s apartment kitchen during our nightly round of food and political conversation, I asked what the point of the free Maduro protests was. Did anyone really think that street protests were going to influence a US decision to drop its fabricated charges against Nicolas Maduro and First Lady Cilia Gomes, whose only “crime” appeared to be standing next to President Maduro when the kidnapping goons arrived?

My roommate, and fellow TeleSur correspondent Osvaldo Zayas said, “A CIA team has just arrived in Caracas and they are certainly going to try to start Gen Z revolution-style protests. The point of tomorrow’s protest is to show a sign of force by the organized left to send a signal to them that things won’t be as easy as they think. If it flops, they will move forward quickly.”

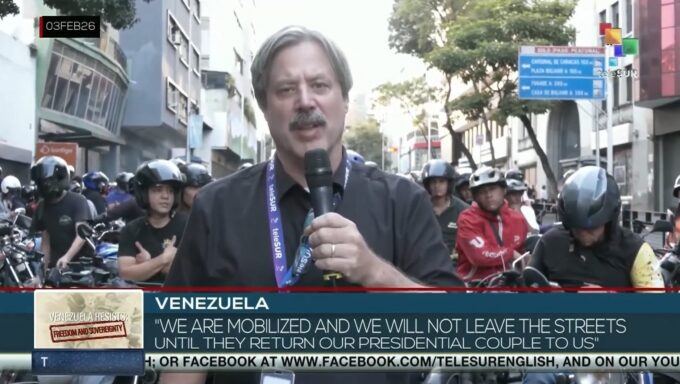

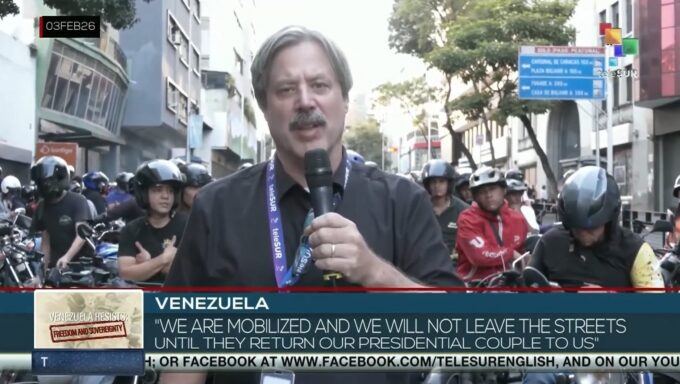

On February 3, tens of thousands of people marched through downtown Caracas for the largest free Maduro protest yet. Although no official crowd size estimate was generated, at it’s height, I observed a dense, moving crowd fully occupying 4 city blocks of a four lane road. One of the marchers, Miladros Rinconez, told me, “We are demanding the release of Cilia and Nicolás. Exactly one month ago, the US. government, represented by the pedophile Trump, invaded Venezuelan soil, killing over 100 compatriots. We are mobilized, and we will not leave the streets until they return our presidential couple to us. And we reaffirm our support for Acting President Delcy Rodríguez Gómez.”

Free Maduro march in Caracas on February 3.

The next day, we headed two hours down from the mountains to the city of Maracay, in Aragua state,for a rally commemorating the 34th anniversary of the Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement 200 rebellion, led by Hugo Chavez against IMF-imposed austerity cuts. Maracay was the city where the rebellion kicked off, and although it was eventually crushed, Lieutenant Colonel Chavez emerged from prison 5 years later and was elected President in 1999.

We expected this to be a show of force by “the machine”, the nickname given to the working class left political network of communes, government workers, cooperatives, citizens militias, union workers and local party officials that forms the base of the ruling PSUV party, and turnout proved to be larger than expected. The crowd that was easily twice, possibly even three or four times the size of the February 3 march in Caracas, in a city with less than 1/3 of its population.

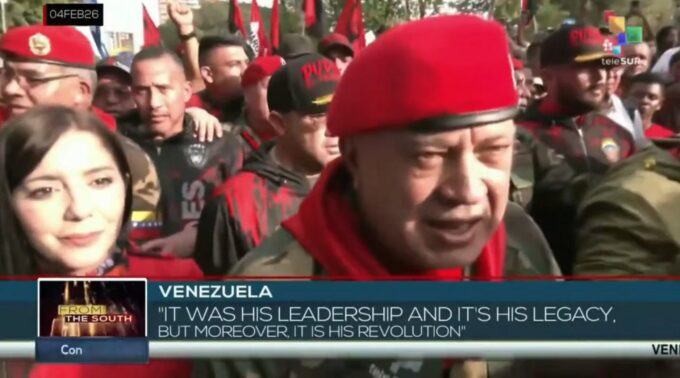

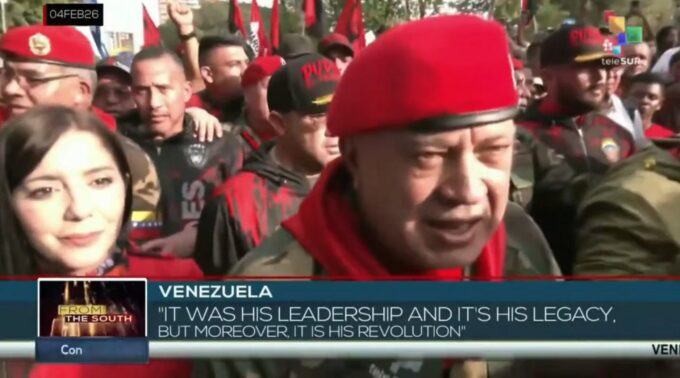

After racing back and forth through a moving crowd for two hours, my cameraman and I arrived at the end point of the march, only to discover that we had only been filming a small portion of it in front of the first sound car. Tens of thousands of people of all ages continued to stream in for another hour. This march was larger than the largest campaign rally I covered during the 2022 elections in Brazil, the massive Lula rally on final day before the election on Paulista and Augusta avenues in Sao Paulo. We doubled back and found my co-worker Osvaldo interviewing Diosdado Cabello, who participated in the 1992 rebellion as an army Captain and is currently Venezuela’s Minister of Interior, Justice and Peace.

“Today is very important,” he said, “you can see the people here on the streets. The people remember Chávez, he is the guide. It was his leadership and it’s his legacy, but moreover, it is his revolution. This is Chávez’s revolution. And we will always come out every February 4th to remember our commander and remind the world why these people rose up.”

Diosdado Cabello.

One thing that stands out in the marches I have covered in Venezuela compared to those in Brazil is that the crowds exercise more discipline. Marches in Brazil are typically accompanied by dozens of beer cart vendors and drum groups and can have a carnaval-like atmosphere. I didn’t see that kind of alcohol consumption in Venezuelan marches. Obviously one factor is that public drinking is illegal in some places, but even the bars along the routes didn’t seem very crowded. In Maracay, in addition to the kinds of social movements and organizations associated with the “machine”, entire families were out on the street. There were thousands of students and signs and banners calling for freedom for Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores were everywhere.

On February 12th, 1814, when Spanish forces attacked the city of Caracas thousands of students joined the battle. After a day of fighting the Royalists fled to the mountains. It was a key victory in the war of Independence, and in memory of the students who fought, the day is now a holiday known as National Youth Day. On February 12, 2026, high school and university students were gathering on Plaza Venezuela to march 6 kilometers through downtown Caracas.

Since some analysts weave a narrative that Latin American working class, organized left movements are aging and the only people who still support the socialist cause are over the age of 50, this would be a good test. I was pleasantly surprised to see tens of thousands of youth on the streets, demanding freedom for Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores.

Natasha Coronado, a teenager from the Miranda chapter of the Venezuelan High School Students Federation, told me, “Today, our greatest battle is not with a rifle—it is in books, it is in the historical consciousness of our youth, and in defending our peace. That is why today we students march with joy, but at the same time we march to demand the prompt return of our constitutional president, our builder of victories, Nicolás Maduro, and our first combatant, Cilia Flores. Today, the youth supports them, and we also march with the same spirit as José Félix Ribas and Robert Serra. Let the students go forth, let the student organizations go forth, and let the Venezuelan High School Student Federation go forth!”

Natasha Coronado.

The international media had been disseminating state department-friendly

disinformation all month. During the first weeks after the missile

attack, caution in issuing visas to journalists from international media

organizations that support the blockade, run continual fluff pieces

about right wing multi-millionaire Maria Corina Machado and label

Nicolas Maduro as a “dictator” was spun as “authoritarian repression of

journalists.” On February 12, the international media both sidesed the student march, insinuating that an opposition protest, the second I had seen since arriving in Caracas, was equal in size, despite photo and video evidence showing there were only a few hundred people there.

My observations of these and other “free Maduro” protests that I witnessed during my month in Venezuela have led me to conclude that the base level support for the Bolivarian transformation to socialism remains strong. The Trump administration’s decision to not challenge the PSUV’s hold on political power in the country, instead merely claiming victory and moving on to their next media circus act, has been at least partially due to the fact that, as in Iran, regime change seems beyond its reach due to the strength of base level support for the government. Whereas large street demonstrations clearly aren’t reflective of the opinions of the entire population, in the case of Venezuela they seem to have been large enough in February, to complicate or at least delay any attempts to trigger a social media fueled “Gen Z rebellion” like the one that recently flopped in Mexico.

This could change depending on how the relationship between Acting President Delcy Rodriguez and the US government develops. For the last month, I have been disappointed to see some analysts on the left repeat the narrative spread by expanded state actors like the New York Times and BBC that acting President Rodriguez has been totally co-opted by the US government, with some pretending it is their own original analysis. This simplistic, social media-friendly narrative avoids a lot of nuance, including the push-back from the Bolivarian government within its adaptation to what appear to be US demands.

I covered the preliminary ratification, two popular consultations and the final ratification of Venezuela’s partial hydrocarbon reform law. Although there are questionable elements to it, it looks like continuity with Nicolas Maduro’s anti-blockade law of 2020, which partially liberalized sectors of the economy, that Steve Ellner framed in Leninist terms as “defensive economic measures”, and an expansion of the government’s long relationship with Chevron. The new reforms maintain state petroleum company PDVSA under 100% public ownership, enabling public private partnerships in the form of 30 year leases on oil fields which can be canceled at any time for breach of contract. This resembles the lease contracts that were ratified in limited form for Brazil’s Pre-Salt reserves during the Dilma Rousseff administration and expanded after the 2016 coup. In a similar manner to Rousseff’s move, acting President Delcy Rodriguez has announced the creation of funds guaranteeing that the royalties will be exclusively used to fund infrastructure, health and education projects. One key difference is that, whereas the Brazilian contracts route 15% of the royalties to the government, the Venezuelan law calls for 30%, including 15% in taxes and 15% in royalties, with exceptions enabled that could bring the total amount down to 25%. After illegitimate coup President Michel Temer took power in Brazil, exceptions were opened up that lowered royalties to 5.9% in a deal struck between the government and BP during the last year of Jair Bolsonaro’s mandate. The biggest red flag in the new petroleum reforms is that the US government is calling for the royalties to be held in a fund in Qatar, under supervision of the US government, which raises the worry that the US will merely steal them as it stole Venezuela’s CITGO gas station chain in the US. Time will tell, however, how this plays out. The US is demanding that these partnerships only apply to US companies, but during her refreshingly short speech to thousands of petroleum workers on the night that the law passed its first parliamentary hurdle, acting President Rodriguez announced that they plan to work with companies from Asia and Europe as well, and said they were closing a natural gas deal with a company from Indonesia. During her speech, Rodriguez also announced that she had been working on the hydrocarbon law reforms for months with President Maduro before his kidnapping, and presented it as an extension of the 2020 anti-blockade law.

The same kind of push-back is clearly visible in the Amnesty law, which is enabling the release of thousands of political prisoners from parole and incarceration, but clearly lists a series of exceptions in article 8, which exempt a series of crimes including murder, human rights violations, and public support for the murderous blockade and US invasion of Venezuela. According to the new law, neither Edmundo Gonzalez nor Maria Corina Machado, the most ridiculous example of a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate since Henry Kissinger, would qualify for amnesty. Acting President Rodriguez made this clear in her February 12 interview with NBC when, asked about Maria Corina Machado, she said, “with regards to her coming back to the country, she will have to answer to Venezuela. Why she called upon a military intervention, why she called upon sanctions to Venezuela, and why she celebrated the actions that took place at the beginning of January.”

During the interview she also made it clear that she does not consider herself to be President of Venezuela. “I can tell you President Nicolás Maduro is the legitimate president,” she said. “I will tell you this as a lawyer, that I am. Both President Maduro and Cilia Flores, the first lady, are both innocent.”

The morning of the kidnapping, a State Department-friendly narrative immediately viralized that someone at the top level of the Venezuelan government had betrayed Nicolas Maduro. “Why was it so easy? It went, “why didn’t anyone fight back.” On social media, it took wings, with Pepe Escobar making yet another of his typically fantastic claims that a (non existent) Russian battalion had rushed to the scene only to be driven back by a group of Venezuelan bodyguards. This theory was immediately debunked when it came out that 32 Cubans and dozens of Venezuelans had been killed during the kidnapping. Why didn’t the much hailed Russian anti-aerial defense system work? One possibility is that the US and France aren’t the only countries that pawn off outdated military equipment to their allies. But reports have surfaced that the US jammed the phone, radio and internet communications systems minutes before the attack. Trump has bragged about using a secret weapon in the attack and eye witness accounts suggest that artificial intelligence was used in the helicopter gunships as they illegally encroached onto Venezuela’s sovereign territory. TeleSur correspondent Osvaldo Zayas spent the second half of February interviewing friends and family members of victims of the US attack. He told me that one of the victims, a 19 year old Venezuelan soldier, was hit with a missile within seconds of firing his first shot at a US helicopter. “His friends told me it seemed like an automated response that immediately pinpointed the location of the gunfire. His body was carbonized with his arms still locked in the firing position.”

To date, no evidence has surfaced of any betrayal at top levels of the Venezuelan government, and the behavior of Venezuelan leadership indicates that they are united. These leaders include Congressman Nicolas Maduro Guerra, son of the kidnapped President, who regularly appeared in public alongside Delcy Rodriguez, congressional president Jorge Rodriguez, and Diosdado Cabello. The alliance between Maduro Guerra with the acting President and Bolivarian government can be interpreted as evidence against the “betrayal” narrative.

In closing, I would like to emphasize that I am not a Venezuela specialist. I am a just a journalist who has spent a few months in Venezuela over the past 5 years. This story is the result of my observations covering Venezuelan politics between January 23 and February 22, 2023. For more leftist analysis of what is happening in Venezuela I suggest not giving too much credence to people who have made careers for themselves as “ex-chavistas” and triangulating sources with different Venezuela-based news and analysis outlets including TeleSur, Mission Verdade, and Venezuela Analysis. Although the signs of push-back give me hope for the future of the Bolivarian government, it’s clear that the imperialist United States has deeply encroached on the sovereignty of the Venezuelan people. As Kawsachun News’ Camila Escalante tells me, “Venezuela is being robbed at gunpoint while trying to negotiate a hostage crisis.” As I left Venezuela on February 22, I noticed that the wanted signs for Edmundo Gonzalez were still on display in the Caracas airport.

This first appeared on Brian Mier’s Substack, De-Linking Brazil.

Brian Mier is a native Chicagoan who has lived in Brazil for 25 years. He is co-editor of Brasil Wire and Brazil correspondent for TeleSur English’s TV news program, From the South.