What is most revealing about the MAGA aesthetic is its studied ugliness. On one side stands the grotesque excess of beauty-pageant femininity, plastic smiles, puffy lips, lacquered beach-wave hair, sharpened jawlines, and a hyper-sexualized nostalgia masquerading as “traditional values.” US Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem exemplifies this aesthetic as a badge of cruelty. Carefully styling herself in a Barbie-doll register of hyper-femininity, she delivers media performances staged in front of prisons and other sites associated with the punishment and terrorization of immigrants. The effect is chilling: a glossy, pornographic aesthetic fused with images of confinement, state violence, and racialized cruelty. Beauty here does not soften power; it aestheticizes domination and makes authoritarian violence appear natural, even glamorous. This aesthetic of cruelty is not confined to clothing (heavy on tweeds), posture, or setting. It increasingly takes hold at the level of the face itself, where artificiality is no longer concealed but aggressively displayed.

As Inae Oh observes in Mother Jones, perhaps “the most jarring element of this burgeoning MAGA stagecraft is its unbridled embrace of face-altering procedures: plastic surgery, veneers, and injectable regimens of Botox and fillers.” Artificiality here is no longer a flaw to be concealed but a badge of belonging, a visual shorthand for power, wealth, and ideological conformity. As one Daily Mail headline bluntly declared, “Plastic surgery was the star of the show” at the Republican National Convention in 2024. The resulting look, widely disparaged as “Mar-a-Lago face,” signals a politics that treats the body as a surface to be engineered, disciplined, and branded, a mask of dominance and emotional vacancy masquerading as strength. The face becomes armor – hard, synthetic, and affectless – training its wearer to project authority while erasing vulnerability.

Traditional Feminine and Masculinist Style

If this surgically enhanced, hyper-feminized spectacle provides one face of the MAGA aesthetic, what Maureen Lehto Brewster has described as “an almost Fox News anchor look” that signals “dressing in [an] overtly feminine way to reassert patriarchal dominance,” its other face emerges in a parallel masculinist style that draws even more directly from the visual grammar of fascism. Shaved or tightly cropped hair, rigid posture, militarized clothing, and the revival of authoritarian silhouettes unmistakably echo twentieth-century fascist pageantry. Consider Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino’s long black trench coat, worn not for function but for theatrical authority. It is costume politics, a visual performance of domination meant to intimidate rather than persuade. As Arwa Mahdawi remarks in The Guardian, “the Zambian bum-stick chimps seem positively sophisticated in comparison.”

Together, these aesthetic registers do more than signal allegiance. They train bodies to feel power before thinking about it, rehearsing domination as posture, style, and presence, a lesson that now circulates with particular intensity across digital culture. This aesthetic hardens further in the digital sphere. MAGA men proliferate across TikTok, YouTube, X, and other platforms like a fever dream of authoritarian masculinity. They present themselves as strongmen-in-training: squared jaws clenched in permanent hostility, hyper-muscular bodies forged in gym rituals that double as moral theater, libidinal excess mistaken for strength, and rigid, armored postures that signal domination rather than confidence. Their movements are stiff and rehearsed, their bodies disciplined into what Wilhelm Reich once called crippling body armor, where repression congeals into aggression, and vulnerability is converted into cruelty.

Pedagogy of Violence

This is not merely a style; it is an embodied pedagogy of violence. These men learn power through posture, gaze, and gesture. Clenched fists, growling stares, and exaggerated physical presence rehearse domination as a way of being in the world. Misogyny and hostile sexism are not simply beliefs but bodily dispositions, ways of standing, moving, and occupying space that render women, queer bodies, migrants, and the “weak” as threats to be neutralized rather than human beings to be encountered. It is therefore no accident that this aesthetic and affective training culminates in the celebration of ICE, an updated Ku Klux Klan in military dress, where white supremacist terror is bureaucratized and legalized, folded into official policy, and normalized as the everyday practice of state power.

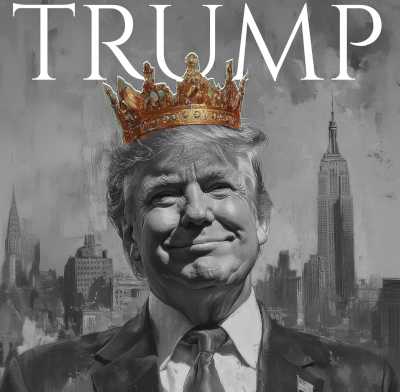

The MAGA aesthetic is tethered to Trump’s regressive theater of white masculinity, a spectacle of grievance, racial resentment, and performative cruelty masquerading as strength. These bodies are drawn to Trump because he licenses their rage. His performance of white supremacy, racism, and nationalist victimhood authorizes the conversion of fear into aggression and resentment into entitlement. What parades as confidence is, in fact, fragility armored with force.

The MAGA male aesthetic is saturated with an evolutionary fantasy of domination: a Hobbesian survival of the fittest worldview stripped of ethics, solidarity, and care. Etched into their faces is a sneer aimed at the “weak,” the feminized, and the racialized other is not incidental; it is central. Violence is already present, normalized through repetition. These bodies function as rehearsals for cruelty, training grounds for a politics in which empathy is viewed with disdain as a weakness, democracy is feminized, and power is proven through the capacity to humiliate, exclude, and harm.

What we are witnessing is more than bad taste or digital bravado; rather it is the corporeal staging of authoritarian desire, a fascist aesthetic that teaches men to feel powerful by hardening themselves against the claims of others. It is violence before the blow, domination before the command, pedagogy before policy.

The MAGA aesthetic is not accidental. Fascist movements have always understood aesthetics as pedagogy, as a way of training people to feel power before they are allowed to think about it. Walter Benjamin warned that fascism aestheticizes politics to mobilize the masses without granting them rights, replacing democratic participation with spectacle, ritual, and submission. Susan Sontag likewise observed that fascist aesthetics glorify obedience, hierarchy, and the eroticization of force, transforming domination into visual pleasure and cruelty into style. In Sontag’s terms, the spectacle does not merely depict power, it trains the eye to desire it. The MAGA look follows this script precisely. It abandons democratic appeal for spectacle, substituting ethical substance with visual aggression and emotional coercion. Its ugliness mirrors its politics: cruel, nostalgic, obsessed with hierarchy, and openly hostile to pluralism. What we see here is not bad taste but a deliberate visual language of authoritarianism, an aesthetic designed to normalize exclusion, glorify force, strip joy and imagination from public life, and prepare the ground for repression.

Nowhere is this aesthetic logic more nakedly visible than in Trump himself, whose body has always functioned as a political text. His appearance is not incidental to his power but central to it, staging domination, excess, and entitlement as visual norms. To read Trump’s look closely is to see how authoritarian values are worn on the body long before they are imposed as policy.

As Jess Cartner-Morley notes, “to critique the Trump aesthetic is not to trivialize abominations, because his values and beliefs run through both. It [begins] at face value, where Trump’s brazenly artificial shade of salmon reflects not only vanity,” but a grotesque misunderstanding of authority, as if a three-week Caribbean cruise tan were an appropriate look for a man entrusted with the gravest responsibilities of public office. His oversized suits and perpetually overlong ties do similar symbolic work. The ties hang like exaggerated phallic markers, extending well past the belt line, signaling not elegance but compulsion, a visual overreach that mirrors his politics. They do not finish the outfit; they dominate it. The result is a body styled not for restraint or dignity but for excess, spectacle, and domination, a supersized ego draped in fabric and color.

All of this is engineered by a president who wears ill-fitting designer suits, commandeers cultural institutions such as the Kennedy Center to impose a politics of vulgarity, and casually announces imperial ambitions, from Greenland to Venezuela. It would be easy to dismiss him as a narcissistic clown. That would be a mistake. He is a demagogue who despises democracy, targets people of color, revels in violence, and has worked to create a personal Gestapo-like police apparatus unaccountable to law. He has elevated staggering levels of inequality and white supremacy into governing principles, funded the genocide in Gaza, and aligned himself on the global stage with war criminals. He appears most animated when humiliating others or inflicting pain. He is the embodiment of an ugly ideology clothed in an equally ugly aesthetic. And in ugly times, such symbols are not incidental; they are warnings.

Henry Giroux (born 1943) is an internationally renowned writer and cultural critic, Professor Henry Giroux has authored, or co-authored over 65 books, written several hundred scholarly articles, delivered more than 250 public lectures, been a regular contributor to print, television, and radio news media outlets, and is one of the most cited Canadian academics working in any area of Humanities research. In 2002, he was named as one of the top fifty educational thinkers of the modern period in Fifty Modern Thinkers on Education: From Piaget to the Present as part of Routledge’s Key Guides Publication Series.