Flags of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the People's Republic of China. CC BY-SA 4.0

September 21, 2025

By Jumel Gabilan Estrañero, Latrell Andre C. Manguera, Chelsy Dianne Giban, Fordy Tic-ing Ancajas and Keith Justine Michael G. Banda

On August 29, 2025, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA)[1] released its independent yet quite intriguing stance on the geopolitical controversy of Taiwan and China. Accordingly, the DFA emphasized that the 1975 Joint Communiqué between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China remains a cornerstone of our longstanding bilateral relationship.

Added to that, “in line with the One China Policy, which the Philippines has consistently upheld, the Government of the Philippines does not recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state. This policy is clear and unwavering.

At the same time, the Philippines maintains economic and people-to-people engagements with Taiwan, particularly in the areas of trade, investment, and tourism. These interactions are conducted within the bounds of our One China Policy.

Consistent with the Philippines’ One China Policy, no official from Taiwan is recognized as a member of the business delegation that recently visited the Philippines.

Given our geographical proximity and the presence of approximately 200,000 Filipinos working and residing in Taiwan, the Philippines has a direct interest in peace and stability in the region. We therefore continue to call for restraint and dialogue. We leave it to the Chinese people to resolve Cross-Strait matters.”

A day before DFA released the diplomatic communique, a Senate hearing[2] was conducted. Presided Sen. Imee Marcos, she then asked officials of the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA)[3] to clarify the Philippines’ position on the One China policy during a public hearing. Sen. Marcos noted that a lot of people are confused on the issue. “As they say… we all know that if there is a confrontation over Taiwan between China and the United States, there is no way that the Philippines can stay out of it simply because of our physical geographical situation. If there is an all-out war, we will be drawn to it. The situation is confusing and above all, its scary. Just to put it on record, as far as the committee is concerned, the Philippines and the U.S. both still recognize the One-China policy, is that correct?” Marcos inquired.

In retort, Foreign Affairs Sec. Ma. Theresa Lazaro said that based on the 1087 Joint Communique of the Philippines and China, the Philippines does not recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state. “We leave it to the Chinese people to resolve cross-strait matters. Conflict will have an impact on geographically proximate territories and the President did not deviate from our principle of non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, a principle of the joint communique,” Lazaro clarified. The One China policy is the acknowledgment by a country that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland being its sole legitimate government, and that Taiwan is a part of China.

In a political economy analysis by Mr. Manguerra, he laid down the foundation of China’s claim. The fall of the Qing Empire in 1912–which ended imperial China–paved the way for the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). This era saw the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and the Communists, which led to the later division of China. Following this are as follows:

• Partition of China. After the civil war, Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China (PRC) took over the Chinese mainland, while Chiang Kai-Shek’s ROC retreated to Taiwan, creating competing claims of legitimate sovereignty internationally.1

• Prologue & Formalization of Relations. Diplomatic engagement between the Philippines and the PRC began in 1974, which resulted in the signing of the PRC-Philippines joint communiqué in 1975, which officially recognized the PRC under the One China Principle.

• Pragmatic Balance of Ties. Since 1975, the Philippines has walked a pragmatic fine line. The Philippines has vibrant economic relations with the PRC, while keeping the boiling tensions at bay in the West Philippine Sea. At the same time, Manila has informal relations with Taipei in the areas of culture, labor, trade, and technology.

• Political Economy in the 21st Century. The “One China Principle” remains a core component of the diplomatic relations of the Philippines. China is among the top trading partners of the Philippines while there is continuous interaction not only in the unofficial economic and cultural sectors but also in the people-to-people contacts with Taiwan. When a diplomat from the ROC visited Manila in 2025, it incited anger from Beijing which prompted the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs to reaffirm that it does not recognize the sovereignty of Taiwan.

The relationship between the Philippines and China can be traced back through its historical and economic roots. On June 9, 1975, a diplomatic relationship between China and the Philippines was formally established, and nearly 100 bilateral agreements that cover different political aspects: trade, infrastructure, etc, were created. However, tension arises between them, particularly the territorial dispute over the West Philippine Sea, also known as the South China Sea. And with recent remarks of President Bongbong Marcos Jr. regarding the China and Taiwan dispute, stressing “There is no way that the Philippines can stay out of it simply because of our geographic location“, and if there will be one, he would ally with the United States to defend Taiwan from China. In which the Chinese foreign ministry responds that it is contradictory to the 1975 agreement between Philippines and China to respect one’s sovereignty, which includes the “One China” Policy.

Meanwhile in most recent assertion, the People’s Republic of China (PRC)[4] has been strong on pushing for the narrative since last year that Taiwan has been Chinese territory since ancient times. They claim that from 1895 to 1945, Taiwan had been occupied and colonized by Japan. In 1945, the Chinese people won the great victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, ending Taiwan’s half-century of humiliation under Japanese slavery.

To beef up its claim, China is legally cited the Cairo Declaration issued by China, the United States and the United Kingdom in December 1943; stating that it was the purpose of the three allies that all the territories Japan had stolen from China, such as Northeast China, Taiwan and the Penghu Islands, should be restored to China (an expressed claim by PRC). Another pre-owned basis is culled from the Potsdam Proclamation, signed by China, the United States and the United Kingdom in July 1945 and subsequently recognized by the Soviet Union, reiterates, “The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out.” On October 25, 1945 the Chinese government announced that it was resuming the exercise of sovereignty over Taiwan, and the ceremony to accept Japan’s surrender in Taiwan Province of the China war theater of the Allied powers was held in Taipei. The return of Taiwan to China constitutes an important component of the post-World War II international order.

What is interesting is that China also used Philippines for its narrative when it cited Pres. Marcos’ statement. It said that in January 2024, President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. publicly reiterated that the Philippines adheres to the one-China policy, and that the Taiwan is a province of China but the manner in which they will be brought together again is an internal matter.

Analysis

1. The US and China contestation

Internal calls for debates have emerged regarding this underlying issue with some even leveraging the Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States to strengthen strategic ties.

At the backdrop of this, the U.S. establishment of the “One China” policy is an act to maintain a balance in relations with both China and Taiwan. One of the aims of this policy is to maintain peace in the Taiwan Straits to insist on a peaceful resolution being done by both countries without interference from any third parties. However, looking at a different lens, although not specifically mentioned, the policy also functions as an instrument for political economy, ensuring continued access to markets, resources, and investments. This allowed the U.S. to open trade and invest with China, while still maintaining unofficial economic ties with Taiwan. This is the same as the Philippines, with economic and diplomatic relations with China, as well as unofficially with Taiwan. The Philippines benefits from stability, trade, and investment under this policy, but places itself in the middle, especially with the tensions arising in the West Philippine Sea.

If we consider the broader context, we can observe that the United States’ interpretation of the “One-China Policy” afforded them a strategic position to balance their relationship with China while simultaneouslyexerting influence over Taiwan. Given the ambiguity and open-ended nature of the “One-China Policy,” the United States can maintain economic relations with Taiwan while simultaneously acknowledging China’sjurisdiction over Taiwan. This is because the United States has its own business and interests in Taiwan,just as China does. Both nations recognize Taiwan’s geographical and economic potential to contribute to theUnited States’ economic agenda. Consequently, they have chosen to ignore the disputed status of thecountry. Both China and the United States are engaged in a global competition for hegemony, which has ledthem to become the “Modern Colonialists”, they do not engage in physical war but an economic wat. Their objective is to seize control of any potential resources or territories they perceive as advantageous throughassertive dominance or strategic economic maneuvers.

2. Precarious Exchange: Philippines in the Middle of Modern Cold War

Even with increased regional tensions, the Philippines continue economic exchanges with Taiwan but strictly within the framework of One China Policy.

Meanwhile, keeping the One China Policy avoids the Philippines from being antagonistic towards the PRC, an emerging regional hegemon, and maintains Philippine access to trade, investment, and strategic leverage. While informal ties with Taiwan permit Philippines to hedge strategically, it also indicates to China that Philippines has room for flexibility with diplomatic relations and has an independent diplomatic cerebrum. This strategic yet pragmatic actions allow the Philippines to extract benefits and engage selectively with both sides – all with the Philippine national interest in mind.

Perhaps the better question to ask here is “Given that China already possesses everything it needs, whatdoes China want from Taiwan?” and “What Taiwanese possession or ownership does the Chinesegovernment seek to assert its dominance over?” The answer lies within the landscape of Taiwan — they are the largest global manufacturer of chips or semi-conductors, has become a dominant force in the technological market, captivating the attention of the “power-hungry” Chinese government. They aim to seize control of the global chip market due to the increasing demands of globalization. China could have just abandoned Taiwan and allows to exercise their own sovereignty a long time ago, but they could not, given the fact that they see the potential in Taiwan to be their economic resource and to further boost their end goal by take over the global market free from the West.

3. Assertive Response yet Calculated

Evidently, the Philippines strengthened ties with countries such as Australia and Canada through joint drills to counteract China’s ever-growing presence, marking a show of force by rising middle-power countries.

Incidentally and strategically, President Marcos Jr. has acknowledged that the Philippines cannot avoid the conflict between Taiwan and China due to its geographic proximity and the presence of over 200,000 OFWs in Taiwan. This vulnerability is heightened by China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea and its warnings over Philippine engagement with Taiwan, underscoring how the issues are interconnected.

From a political economy perspective, the Philippines is caught in a “tug-of-war,” as any escalation regarding Taiwan could draw it into regional conflict while threatening economic stability. The Department of Foreign Affairs’ affirmation of the “One China” Policy reflects the country’s attempt to balance security commitments with the U.S. and economic ties with China and Taiwan.

Furthermore, when it comes to the Philippines and the “One-China Policy,” the government’s stance isa smart move, but it is also risky. Throughout history, the Philippines has been caught between the two hegemons: China and the U.S., and it has been playing tug-of-war with them. It is better to choose one or the other than to be a puppet on their strings. The stance of the administration is understandable as it gears towards preserving the territory of the Philippines and its right to self-determination. But then again, Filipinos must be vigilant of the ongoing tension between the two superpowers.

4. Balancing Development and Defense

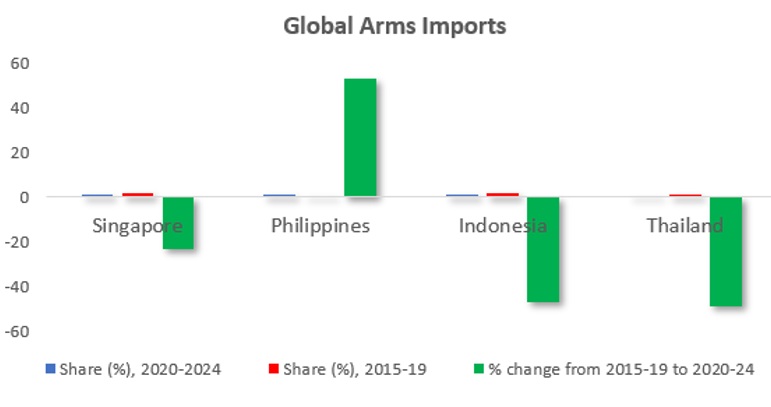

Economic revitalization is something the Philippines need. Engaging with the PRC establishes essential investments, trade, and infrastructure flows that could result in domestic growth, industrialization, and job creation. Informal ties with Taiwan also supplement economic and technological growth, while OFWs in China and Taiwan send remittances and establish human capital that support the overall national development. If Manila were to spur Chinese anger by overexposing itself to Taiwan, bilateral economic coercion, trade gap measures, or capital flight could threaten Philippine growth.

Financial software

The boiling tensions between the PRC and Taiwan (ROC for China mainland’s self-assertion) is not a foreign reality for the Philippines. Like Taiwan, the Philippines is also experiencing Chinese bullying in the West Philippine Sea. In the Cross-Strait context, Pres. Marcos Jr. is realistically correct that if a war breaks out in the Taiwan Strait, the Philippines would be drawn inevitably because of its association with the U.S. through the Mutual Defense Treaty, as the U.S. commits to defend ROC. This challenging reality explains why retaining the One China Policy is primordial, because it allows the country to respond to regional pressures in a pragmatic way that protects the nation’s economic and security interests.

Implications and Some Recommendations

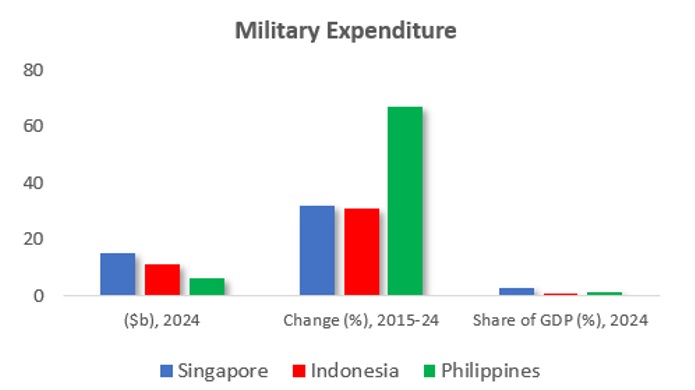

1. We recommend maintaining the adherence of the Philippines to the “One China” Policy to maintain a peaceful and stable relationship with China.[5] Any diplomatic fallout would backfire on the Philippines, as the reality is that the country is weak in terms of military and economic aspects, still depending on outside nations. Adding to this is the ongoing tension regarding the West Philippine Sea. The Philippines’ adherence to the “One China” policy is, therefore, a necessary form of strategic. By maintaining this policy, the Philippines will avoid being directly involved in the cross-strait politicaldispute[6]. And if the latter happens in the future, the Philippines will act as a neutral party. Focused its resources on protecting its people and securing its territory.

2. To mitigate any significant risks of a potential conflict between China and Taiwan. First, deepened the ties with Taiwan. Although acting as a de facto, the key role that Taiwanese companies hold in the manufacturing of electronics and technology should continue to benefit the Philippines in both ways. Also, it is recommended to diversifying economically and strengthening further trade partnerships to reduce dependence on China. One way is to deepen the connection to intra-ASEAN trade to leverage regional supply chains. Relevant today is to explore new market trends, especially those that are known for their renewed technology (Japan) and financing.

3. It is recommended to take an active neutral stance and strengthen thesecurity of these forces under the defense and security department: Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the Office of Civil Defense (OCD), the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO), the National Defense College of thePhilippines (NDCP), the Government Arsenal (GA), and Veterans Memorial Medical Center (VMMC) with supports from National Security Council (NSC), DTI, and the DEPDEV (formerly NEDA). The Philippines must innovate and invest in new and effective dynamics that will safeguard the Philippines from any threats (whether internal or external actors).

To wit, the Philippine Government strikes a balance between economic and political interactions with conflicted countries like Taiwan, China, and the United States. By establishing a balanced economic partnership with these nations, we can minimize the risk of potential conflicts. Additionally, we should strengthen our connections with our allies within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as they are crucial in enhancing our economic security reducing the reliance on the two hegemons.

Conclusion and Way Ahead

In a nutshell, the Philippines’ commitment to the One-China Policy is evident in its long-standing diplomatic stance, as demonstrated since 1975. Indeed, the ‘August 2025 communique’ recognized the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China and acknowledged Taiwan as an integral part of Chinese territory but in a calculated move from Philippine’s fence.

Successive Philippine administrations have consistently upheld this stance, emphasizing respect for China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Executive Department also supports the peaceful resolution of Cross-Strait matters, believing that the Chinese people themselves should resolve them and to avoid escalated and unintended spillovers in Southeast Asian conundrum, yet the Philippines[7] must be prepared in any probable war beyond peacetime. Preparation has always been a key in any grey zone tactics of China.

Despite the recent official diplomatic position, the Philippines maintains robust economic tie-up and people-to-people engagements with Taiwan, particularly in areas such as trade, investment, and tourism. These interactions are carefully conducted within the established bounds of the One-China Policy, reflecting a complex balancing act on its foreign policy. Given its geographical proximity to Taiwan and the significant presence of approximately 200,000 Filipino workers there, the Philippines has indeed a direct interest in regional peace and stability. Consequently, it frequently urges restraint and dialogue in the Taiwan Strait yet here we are, in strategic zen mode of political economy while maintaining peace and security at larger extent in global context.

*Ideas and/or views expressed here are entirely independent and not in any form represent author’s organization and affiliation.

About the authors:

Latrell Andre C. Manguera is an International Development Studies major in De La Salle University, and forerunner of organizational plans & programs in the IDS Council and Christian church (Christ Commission Fellowship / CCF). He is specializing in international relations, sustainable development, and pragmatism in contemporary politics.

Chelsy Dianne Giban is a Political Science major in in De La Salle University, University Student Government Asst. Secretary (Internal), and specializing in cyber-politics, gender and development, public policy, and the emerging sports politics.

Fordy Tic-ing Ancajas is Political Science major in De La Salle University, Deputy Executive Secretary in University Student Government (7th Congress), international law debater, and specializing in Southeast Asian politics, indigenous people’s rights, and human rights.

Keith Justine Michael G. Banda is Political Science major in in De La Salle University specializing in political dynamics and American & European political economy.

[1]DFA Statement on One China Policy, DFA, https://dfa.gov.ph/dfa-news/statements-and-advisoriesupdate/37090-dfa-statement-on-one-china-policy

[2]Senate Public Relations and Information Bureau, https://web.senate.gov.ph/photo_release/2025/0828_01.asp

[3] Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) Secretary Ma. Theresa Lazaro said they have several mechanisms to address the harassment such as the bilateral consultative mechanism, but Committee Chairman Senator Imee Marcos pointed out that the protests do not seem to work. (ABS-CBN, August 28, 2025)

[4] The one-China principle is clear cut. There is but one China in the world. Taiwan is part of China. The Government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole legal government representing the whole of China. UNGA Resolution 2758 fully reflects and reaffirms the one-China principle. On October 25, 1971, the 26th session of the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 2758 with an overwhelming majority. It states in black and white that the General Assembly “decides to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.” (Embassy of the Republic of China in the Philippines, October 8, 2024)

[5] In other words, a good and sedate relationship with China. This is because our stance on “One-China Policy” can be a tool to navigate the dynamics about the ongoing territorial dispute over the West Philippine Sea. Though recently, the Marcos Administration’s actions leaned towards the west, it is still critical to maintain a good relationship with our neighboring country.

This might be a hard pill to swallow that the Philippines is weaker in terms of economy and military compared to what China has, and any misunderstanding of China could lead to unpleasant outcomes as far as the Philippines is concerned. Therefore, the adherence of the Philippines to “One-China Policy” is pivotal in achieving its national interest which is to protect and preserve our territory free from international violence.

[6] For example, Philippines to keep the people-to-people exchanges between China and Taiwan going. Even though the government-to-government relations are on hold, we should still encourage cultural, educational, and tourist exchanges whenever we can. These interactions help us get to know each other better and build a solid foundation of understanding. That could be helpful if we ever need to talk about anything important in the future.

[7] That is why there is big deal on the enhancement of maritime, aerial, and surveillance assets so that the country can effectively deter threats in the West Philippine Sea. The country must use its alliances with like-minded partners responsibly while maintaining a diplomatic equilibrium with China, to keep national security in focus as it tactically seek other ways to deter strategic threats.

[8] He has participated in various NADI Track II dialogues. His articles have appeared in Global Security Review, Geopolitical Monitor, Global Village Space, Philippine Daily Inquirer, Philippine Star, Manila Times, Malaya Business Insights, Asia Maritime Review, The Nation (Thailand), Southeast Asian Times, Global Politics and Social Science Research Network.

Jumel Gabilan Estrañero is a defense, security, & political analyst and a university lecturer in the Philippines. He has completed the Executive Course in National Security at the National Defense College of the Philippines and has participated in NADI Track II discussions in Singapore (an ASEAN-led security forum on terrorism). His articles have appeared in Global Security Review, Geopolitical Monitor, Global Village Space, Philippine Daily Inquirer, Philippine Star, Manila Times, Malaya Business Insights, Asia Maritime Review, The Nation (Thailand), Southeast Asian Times, and Global Politics and Social Science Research Network. He worked in the Armed Forces of the Philippines, Office of Civil Defense, National Security Council-Office of the President, and currently in the Department of the National Defense. He is currently teaching lectures in De La Salle University Philippines while in the government and formerly taught at Lyceum of the Philippines as part-time lecturer. He is the co-author of the books titled: Disruptive Innovations, Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism: A Philippine Terrorism Handbook, and Global Security Studies Journal (Springer Link, United States). He is an alumnus of ASEAN Law Academy Advanced Program in Center for International Law, National University Singapore and Geneva Centre for Security Policy, Switzerland. He is also a Juris Doctor student.