Bees Reveal a Human-Like Collective Intelligence We Never Knew Existed

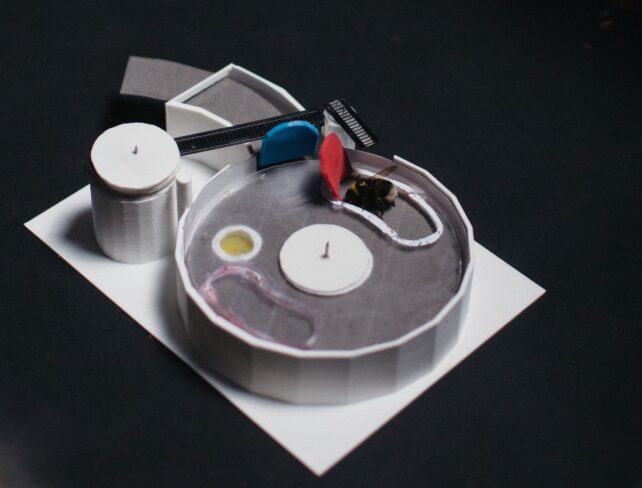

Two bees solving the two-step puzzle. (Queen Mary University of London)

Two bees solving the two-step puzzle. (Queen Mary University of London)The humble bumblebee is proof that brain size isn't everything.

This little insect with its wee, seed-sized brain has shown a level of collective intelligence in experiments that scientists thought was wholly unique to humans.

When trained in the lab to open a two-step puzzle box, bumblebees of the species Bombus terrestris could teach the solution to another bee that had never seen the box before.

This naive bee would not have solved the puzzle on its own. To teach the 'demonstrator' bees the non-intuitive solution in the first place, researchers had to show them what to do and offer them a reward after the first step to keep them motivated.

"This finding challenges a common opinion in the field: that the capacity to socially learn behaviors that cannot be innovated through individual trial and error is unique to humans," write the team of researchers based in the United Kingdom and United States.

Humans have a long history of 'moving the goalposts' on what sets our species apart from all others.

Once, it was thought that humans were the only animals with culture. But 'viral' songs among sparrows, the evolving dialects and traditions of whales, the regional hunting strategies of orcas, and the learned tool tricks of apes, crows, and dolphins, all suggest that socially transmitted behaviors are also present in animal societies, too.

Some of these cultural behaviors even show signs of refinement and improvement over time. Homing pigeons, for instance, learn from each other and adjust their culture's flight paths year on year.

An influential way to move the goalposts on human intelligence is to say that humans are unique from other animals because we can learn things from each other that we could not invent independently.

Think of the device you are reading this article on right now. No one human can invent all its parts and mechanics from scratch on their own and in one lifetime. It's taken decades of work and refinement to get to this advanced stage. Even the very act of reading is a skill that generations of humans have built upon little by little.

Obviously, no animal can put together an iPhone or read an article on animal intelligence. But at a basic level, bumblebees join chimpanzees in "cast[ing] serious doubt on this supposed human exceptionalism," writes Alex Thornton, an ecologist at the University of Exeter, in a review of the bumblebee research for Nature.

Chimpanzees have large brains and rich cultural lives, but the discovery among bumblebees, Thornton argues, is "all the more remarkable because it focuses not on humanity's primate cousins, but on… an animal with a brain that is barely 0.0005 percent of the size of a chimpanzee's."

Underestimated for decades, largely because of their size, bumblebees are finally getting their due.

Recent experiments in the lab show these bees can learn from each other, use tools, count to zero, and perform basic mathematical equations.

The collective intelligence of their hive mind is also not to be dismissed.

To test it, behavioral scientist Alice Bridges from Queen Mary University of London and colleagues housed colonies of bumblebees with a two-step puzzle for a total of 36 or 72 hours over 12 or 24 consecutive days, with no human help.

After all that time, the bees could not figure out how to get to the sugary reward. Bumblebees spend on average about 8 days foraging in their lifetimes, so it's as if they had up to a third of their lifetime foraging time to work on the puzzle.

In the image below, you can see the puzzle. The yellow circle contains a drop of sugar under a plastic lid. Bees can get to it by pushing the red tab, but only once the blue tab has been pushed out of the way.

It took a human to painstakingly show them the way, and this was only possible using an extra reward. But once one bee figured it out, they could teach others how to move the two tabs to retrieve a sugary treat.

A similar experiment on chimps was also published recently in Nature Human Behavior. Both the vertebrate and invertebrate case studies showed a sharing of ideas that were exceptionally hard to learn alone.

Of course, this behavior wasn't observed in the wild. It had to be taught to the bees and chimps first. But the findings leave open the possibility that if there were a rare, once-in-a-lifetime innovator in chimp or bee society – an Einstein among bees – their ideas might stick around in animal culture and be used for generations to come.

Bees' famous honey waggle dance, pointing out the distance, direction, and quality of sources of food, for instance, is a behavior that was once thought to be purely instinctive, but it now appears to be somewhat shaped by social influences.

In 2017, researchers also trained bumblebees to roll a ball into a goal for a reward. To score, the insects had to learn from each other and remedy their previous mistakes. And so they did.

The newest experiment, Thornton writes, "suggests that the ability to learn from others what cannot be learnt alone should now join tool use, episodic memory (the ability to recall specific past events) and intentional communication in the scrapheap" of explanations for human cognition and culture.

The study was published in Nature.

BEES ARE SYMBOLS OF THE AEON OF MAAT

SEE Liber Pennae Praenumbra - Wikisource, the free online library

Why do bees have queens? 2 biologists

explain this insect’s social structure – and

why some bees don’t have a queen at all

The queen, on the right with a larger, darker body, is bigger than the worker bees in the colony and lives several times longer. Jens Kalaene/picture alliance via Getty Images

THE CONVERSATION

Published: March 4, 2024

Associate Professor of Biology, Tufts University

Professor of Biology, Framingham State University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why do bees have queens? – Rhylie, age 8, Rosburg, Washington

When you think “bee,” you likely picture one species that lives all over the world: the honey bee. And honey bees have queens, a female who lays essentially all of the eggs for the colony.

But most bees don’t have queens. With about 20,000 species of bees worldwide – that’s about 2 trillion bees – the majority of them don’t even live in groups. They do just fine without queens or colonies.

Instead, a single female lays eggs in a simple nest, either inside a plant stem or an underground tunnel. She provides each egg with a ball of pollen mixed with nectar that she collected from flowers, and she leaves the eggs to hatch and develop on their own. She doesn’t have anyone to help with this process.

These bee species, often spectacularly beautiful, are important pollinators of many crops and plants, though most people aren’t even aware of them.

Since lots of bees successfully live without a queen, what is it that queens provide for the bee species that do have them? We are behavioral ecologists who study social insects, and this question is at the heart of our research

A queen, workers and drones

Along with honey bees, two other kinds of bees also have queens: bumble bees, which are found on all continents except Australia and Antarctica, and stingless bees, which are found primarily in tropical areas.

One honey bee colony – also called a hive – may have more than 50,000 bees, while bumble bee colonies usually have just a few hundred bees. Stingless bee colonies are often small, but some are as large as the biggest honey bee hives.

These bees’ social structures have two more things in common besides the egg-laying queen: the female workers who care for the colony, and the males, sometimes called “drones.”

Notice the males are not included in the “worker” group. Males generally don’t help collect nectar or pollen, protect and maintain the hive, or care for the young larvae. The females do all of those jobs.

Instead, the males have one task: to find and then mate with a female who may become a future queen. After building their strength, males leave the hive to join thousands of other drones to wait for new queens that are also looking for mates. If males are lucky enough to mate, they die soon afterward. In contrast, females typically mate with many different males before starting their lives as egg-laying queens.

Female worker bees do pretty much all the work.

The isolated queen

Maybe you imagine a queen as the one in charge, ordering everyone around. But that’s a case of language being misleading. Unlike human queens who lead their people, bee queens don’t rule over their workers.

Instead, particularly for honey bees, the queen is rather isolated from what’s happening in the hive. Remember, she just lays eggs, up to 2,000 in a day. The workers surround and take care of her while managing the colony. The queen bee might live for a few years, much longer than female worker bees and drones.

Other animals also live in social groups with a division of labor between those who reproduce and those who maintain the colony. Ants, termites and some wasps – like yellow jackets and hornets – have a similar kind of colony structure. So does the naked mole rat. Why did these groups evolve to have queens?

Family ties

One way for an organism to pass on genes is by having offspring.

Another way is to help close relatives, who are likely to share many of your same genes, to produce more offspring than they would if they were on their own.

This option is pretty much what happens in a bee colony. Those thousands of female worker bees may not themselves reproduce, but the queen is their mother. They help her produce another generation of siblings who will one day be their sisters. In this way, the female worker bees are passing their genes on to the next generation, just not directly.

Something else to consider: A honey bee hive is a wonderfully complex structure. The layers of wax combs built to store honey and raise offspring are a marvel of architecture and require a large workforce for construction, ongoing repairs and protection from intruders or predators.

So you might ask: Which came first? Social groups with queens and workers producing large numbers of related offspring that required more elaborate nest structures? Or did the complex nest arise first, which led to greater success for groups that evolved to divide tasks among queens and workers?

These are fascinating questions that biologists have been exploring for decades. But both of these factors – the division of labor and the complex hive structures – help explain why there are bees with queens.

Kollontai – Love of worker bees

14/10/2009 by Josephine Grahl

No comments:

Post a Comment