The next chapter of lunar exploration could forever change the moon — and our relationship to it (op-ed)

As more lunar exploration initiatives loom, it must be asked: Will we responsibly and sustainably protect future generations' ability to practice scientific and cultural traditions on, near or in relation to the moon? And will we be able to develop a lunar land ethic? With rapidly rising numbers of active governmental and private space actors, and increasing pre-approved, treaty-bypassing space initiatives, it will take courage and vision for any nation(s) to set the intentional precedent of proceeding in ways that honor humanity's scientific-cultural heritage, prioritizing the "right way" rather than "right now."

This feels especially urgent given the first U.S. landing on the moon in 51 years through the U.S.-based, privately-owned Intuitive Machines two weeks ago, carrying scientific experiments as well as human-made "leave behinds" on the lunar surface such as the "Koons moons".

Examples like this urgently require addressing gaps in the language of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the recent Artemis Accords, such as the increasing role of private companies in space and whether their missions, lunar or otherwise, are aligned with the aspirational ideals in the Artemis Accords regarding the preservation of heritage or benefits of space exploration for all of humankind.

Aparna Venkatesan is an astronomer and dark-sky advocate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at University of San Francisco. She works actively on space policy projects and has co-created STEM partnerships with Indigenous communities for almost 25 years. Dr. Venkatesan recently coined the term noctalgia with Dr. John Barentine to express “sky grief” for the accelerating loss of the home environment of our shared skies.

Where will humanity, and the moon, be by the next lunar standstill in the early 2040s?

The moon during a waxing crescent phase.

(Image credit: Valeriano Antonini / 500px)

By Aparna Venkatesan, John Barentine

( s) published 2 days ago

Aparna Venkatesan is an astronomer and dark-sky advocate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at University of San Francisco.

John Barentine is an astronomer, historian, author, science communicator, and founder of Dark Sky Consulting, LLC.

For as long as there have been humans, the moon has been a calendar, ancestor, ritual, inspiration, and origin story for humanity. Its monthly and subtler generational cycles have been — and are still — painstakingly recorded and celebrated by cultures around the world since prehistoric times.

These recurring sequences include the "major lunar standstills" occurring every 18.6 years, when the moon reaches its most northern/southern points, or lunistices, within the course of a single month. We are now entering the period of the latest major standstill in 2024-25.

Two major standstills have occurred since the United States last sent a crewed mission to the moon, Apollo 17 in December 1972. Since that time, only four other countries have joined the small club of countries to successfully achieve soft landings on the moon: The former Soviet Union, China, and since August 2023, India and Japan. Along with spacecraft and crashed pieces of space hardware, humans have left tools, scientific experiments, and even bags of their discarded excrement on our neighboring world.

So we ask in early 2024: Where will humanity, and the moon, be by the next lunar standstill in the early 2040s?

Related: Moon group pushes for protection of ultraquiet lunar far side

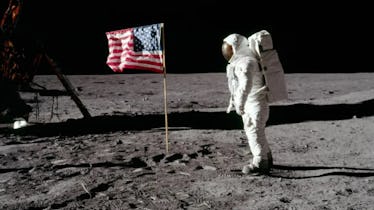

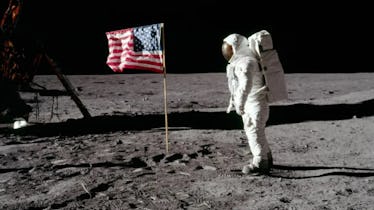

In the 1960s the United States and the Soviet Union vied to be first to achieve the age-old dream of, in U.S. President Kennedy's words, "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth". The crewed Apollo 11 landing on July 20, 1969 was as much a "great leap for mankind" as it was a demonstration not only of the superiority of U.S. technological know-how, but also, some argued, its politico-economic system.

After the fall of the U.S.S.R., its successor state, the Russian Federation, joined the U.S. as a partner in efforts such as the assembly and operation of the International Space Station. It seemed as though the Space Race had ended.

But now a new race to the moon is underway, driven as much by commercial exploitation of lunar resources as by flaunting military power in the new frontier of outer space, and a sense of urgency from "manufactured fear" reflecting Cold War rather than modern collaborative frameworks. As we write this, there are renewed fears of nuclear threats from orbital space following the Russian anti-satellite test of November 2021, which generated space debris that, in the words of the American Astronomical Society, "imperils human spaceflight … the night sky and its accessibility for ground-based astronomy, as well as other scientific, economic, commercial, and cultural purposes."

Because of the changes wrought by human activities since 1959, historians recently argued that the moon has entered a novel phase of its geologic history in which human modification of its surface will vastly outpace the rate of evolution due to natural influences alone. Astronauts returning to the moon in coming years face a world over six decades into this new era, dubbed the "Lunar Anthropocene".

The name of the new lunar era deliberately echoes the Anthropocene of our own planet that increasingly includes its surrounding space environment. In the last seven decades human activity has radically transformed the orbital space near the Earth. Recently, the pace of this change has accelerated at an alarming rate. According to the European Space Agency, the number of known objects orbiting the Earth has doubled just since 2015.

Space debris is similarly proliferating. Collisions between space objects — some accidental, others deliberate — generate cascades of debris, each component of which becomes a collision risk for other objects. Upward of 50 tons of debris may be intentionally deorbited each week by the end of this decade, with unknown consequences for the chemistry of the Earth's upper atmosphere, the ocean and all life on Earth. Additionally, thousands of functional satellites orbiting the planet are already interfering with ground-based observations for radio astronomy as well as optical and infrared astronomy (SATCON1 and SATCON2 reports).

The moon is not far behind. Orbital crowding, environmental degradation and increasing light and radio-frequency pollution are expected consequences of the new lunar space race, mirroring the effects of similar activities near our planet. These developments imperil the potential the moon otherwise shows to host unique scientific research activities, such as the most sensitive radio astronomical measurements ever made from the moon's far side. Soon, the airless moon will no longer be a "quiet" celestial object; rather, it will be bristling with human-generated radio energy.

The moon represents not only shared (solar system) history and scientific opportunity, but also shared heritage and cultural-religious significance to many global cultures, including Indigenous communities.

Current practices by state and private space actors violate cultural beliefs, including in January 2024 when the Astrobotic Peregrine One mission attempted to carry human remains to the moon, resulting in widespread condemnation from Indigenous communities and international outcry.

The Navajo Nation in particular issued a statement to NASA, reminding them of the need for consultation given the 26-year history of this problem which represents a desecration of "a sacred place in Navajo cosmology". There have since been a number of Indigenous-led calls to cease the practice of sending human (and pet) remains to the moon. Thus, the moon is at risk of not only becoming a future war zone but a federally-subsidized grave.

The moon has been our satellite for nearly 4.5 billion years, and despite its annual drift of a few centimeters per year away from Earth, it will remain our closest and most visibly world-like companion for billions of years to come. This makes the current rush to occupy cislunar space and the moon all the more incomprehensible, with an ill-quantified tradeoff between science and security gains versus potentially permanent loss of geological records of early solar system history; environmental and bio-contamination of the lunar surface and atmosphere; and desecration of cultural beliefs around the moon.

By Aparna Venkatesan, John Barentine

( s) published 2 days ago

Aparna Venkatesan is an astronomer and dark-sky advocate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at University of San Francisco.

John Barentine is an astronomer, historian, author, science communicator, and founder of Dark Sky Consulting, LLC.

For as long as there have been humans, the moon has been a calendar, ancestor, ritual, inspiration, and origin story for humanity. Its monthly and subtler generational cycles have been — and are still — painstakingly recorded and celebrated by cultures around the world since prehistoric times.

These recurring sequences include the "major lunar standstills" occurring every 18.6 years, when the moon reaches its most northern/southern points, or lunistices, within the course of a single month. We are now entering the period of the latest major standstill in 2024-25.

Two major standstills have occurred since the United States last sent a crewed mission to the moon, Apollo 17 in December 1972. Since that time, only four other countries have joined the small club of countries to successfully achieve soft landings on the moon: The former Soviet Union, China, and since August 2023, India and Japan. Along with spacecraft and crashed pieces of space hardware, humans have left tools, scientific experiments, and even bags of their discarded excrement on our neighboring world.

So we ask in early 2024: Where will humanity, and the moon, be by the next lunar standstill in the early 2040s?

Related: Moon group pushes for protection of ultraquiet lunar far side

In the 1960s the United States and the Soviet Union vied to be first to achieve the age-old dream of, in U.S. President Kennedy's words, "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth". The crewed Apollo 11 landing on July 20, 1969 was as much a "great leap for mankind" as it was a demonstration not only of the superiority of U.S. technological know-how, but also, some argued, its politico-economic system.

After the fall of the U.S.S.R., its successor state, the Russian Federation, joined the U.S. as a partner in efforts such as the assembly and operation of the International Space Station. It seemed as though the Space Race had ended.

But now a new race to the moon is underway, driven as much by commercial exploitation of lunar resources as by flaunting military power in the new frontier of outer space, and a sense of urgency from "manufactured fear" reflecting Cold War rather than modern collaborative frameworks. As we write this, there are renewed fears of nuclear threats from orbital space following the Russian anti-satellite test of November 2021, which generated space debris that, in the words of the American Astronomical Society, "imperils human spaceflight … the night sky and its accessibility for ground-based astronomy, as well as other scientific, economic, commercial, and cultural purposes."

Because of the changes wrought by human activities since 1959, historians recently argued that the moon has entered a novel phase of its geologic history in which human modification of its surface will vastly outpace the rate of evolution due to natural influences alone. Astronauts returning to the moon in coming years face a world over six decades into this new era, dubbed the "Lunar Anthropocene".

The name of the new lunar era deliberately echoes the Anthropocene of our own planet that increasingly includes its surrounding space environment. In the last seven decades human activity has radically transformed the orbital space near the Earth. Recently, the pace of this change has accelerated at an alarming rate. According to the European Space Agency, the number of known objects orbiting the Earth has doubled just since 2015.

Space debris is similarly proliferating. Collisions between space objects — some accidental, others deliberate — generate cascades of debris, each component of which becomes a collision risk for other objects. Upward of 50 tons of debris may be intentionally deorbited each week by the end of this decade, with unknown consequences for the chemistry of the Earth's upper atmosphere, the ocean and all life on Earth. Additionally, thousands of functional satellites orbiting the planet are already interfering with ground-based observations for radio astronomy as well as optical and infrared astronomy (SATCON1 and SATCON2 reports).

The moon is not far behind. Orbital crowding, environmental degradation and increasing light and radio-frequency pollution are expected consequences of the new lunar space race, mirroring the effects of similar activities near our planet. These developments imperil the potential the moon otherwise shows to host unique scientific research activities, such as the most sensitive radio astronomical measurements ever made from the moon's far side. Soon, the airless moon will no longer be a "quiet" celestial object; rather, it will be bristling with human-generated radio energy.

The moon represents not only shared (solar system) history and scientific opportunity, but also shared heritage and cultural-religious significance to many global cultures, including Indigenous communities.

Current practices by state and private space actors violate cultural beliefs, including in January 2024 when the Astrobotic Peregrine One mission attempted to carry human remains to the moon, resulting in widespread condemnation from Indigenous communities and international outcry.

The Navajo Nation in particular issued a statement to NASA, reminding them of the need for consultation given the 26-year history of this problem which represents a desecration of "a sacred place in Navajo cosmology". There have since been a number of Indigenous-led calls to cease the practice of sending human (and pet) remains to the moon. Thus, the moon is at risk of not only becoming a future war zone but a federally-subsidized grave.

The moon has been our satellite for nearly 4.5 billion years, and despite its annual drift of a few centimeters per year away from Earth, it will remain our closest and most visibly world-like companion for billions of years to come. This makes the current rush to occupy cislunar space and the moon all the more incomprehensible, with an ill-quantified tradeoff between science and security gains versus potentially permanent loss of geological records of early solar system history; environmental and bio-contamination of the lunar surface and atmosphere; and desecration of cultural beliefs around the moon.

As more lunar exploration initiatives loom, it must be asked: Will we responsibly and sustainably protect future generations' ability to practice scientific and cultural traditions on, near or in relation to the moon? And will we be able to develop a lunar land ethic? With rapidly rising numbers of active governmental and private space actors, and increasing pre-approved, treaty-bypassing space initiatives, it will take courage and vision for any nation(s) to set the intentional precedent of proceeding in ways that honor humanity's scientific-cultural heritage, prioritizing the "right way" rather than "right now."

This feels especially urgent given the first U.S. landing on the moon in 51 years through the U.S.-based, privately-owned Intuitive Machines two weeks ago, carrying scientific experiments as well as human-made "leave behinds" on the lunar surface such as the "Koons moons".

Examples like this urgently require addressing gaps in the language of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the recent Artemis Accords, such as the increasing role of private companies in space and whether their missions, lunar or otherwise, are aligned with the aspirational ideals in the Artemis Accords regarding the preservation of heritage or benefits of space exploration for all of humankind.

Aparna Venkatesan is an astronomer and dark-sky advocate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at University of San Francisco. She works actively on space policy projects and has co-created STEM partnerships with Indigenous communities for almost 25 years. Dr. Venkatesan recently coined the term noctalgia with Dr. John Barentine to express “sky grief” for the accelerating loss of the home environment of our shared skies.

UK space chief flags moon mining as next conflict ‘gray zone’

By Sebastian Sprenger

Thursday, Mar 7

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/FLTNX2LKGNDW7IC3WBAQHJFPFA.jpg)

By Sebastian Sprenger

Thursday, Mar 7

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/FLTNX2LKGNDW7IC3WBAQHJFPFA.jpg)

This photo taken on May 5, 2023 shows the moon during a penumbral lunar eclipse in Indonesia. (Chaideer Mahyuddin/AFP via Getty Images)

FARNBOROUGH, England — Mining rare minerals on the moon could mark a new area of competition in space, though it’s too early tell whether the prospect would entail military involvement, according to the U.K.’s top military officer for space.

A scenario of nations jumping on lunar mining to refill their dried-up, terrestrial stocks has the potential for gray zone conflict, the kind of amorphous contest that transcends traditional notions of two warring parties shooting at each other, Air Vice-Marshal Paul Godfrey said at the Space Comm Expo trade show here.

For now, there is no commercial proposition for what Godfrey likened to a science fiction version of the U.S. Gold Rush of the nineteenth century.

“The cost of getting to the moon, creating a lunar base, extracting the minerals and getting them back to earth probably far outweighs mining precious minerals on the Earth,” he told Defense News in an interview.

It’s also still unclear exactly what types of rare-earth metals, critical in producing high-tech components, exist under the lunar surface. On Earth, China is a critical supplier of such ingredients. European and NATO nations are eager to diversify their supply chain as they view Beijing as an unreliable partner politically.

Godfrey characterized developments toward lunar mining as purely commercial, but, by raising the matter, made clear it has started to pop up on the radars of armed forces, with very practical questions emerging.

“Do you ring-fence your particular area on the moon if you strike gold, so to speak?” Godfrey asked.

Whether moon mining will become feasible one day depends on key technologies and ensured access to space for all, he said, adding that proliferating space debris could make the journey impossible for everyone at some point.

Reducing the cost of space launches and advancing the field of on-orbit manufacturing also are stepping stones to the vision of moon mining, Godfrey added.

FARNBOROUGH, England — Mining rare minerals on the moon could mark a new area of competition in space, though it’s too early tell whether the prospect would entail military involvement, according to the U.K.’s top military officer for space.

A scenario of nations jumping on lunar mining to refill their dried-up, terrestrial stocks has the potential for gray zone conflict, the kind of amorphous contest that transcends traditional notions of two warring parties shooting at each other, Air Vice-Marshal Paul Godfrey said at the Space Comm Expo trade show here.

For now, there is no commercial proposition for what Godfrey likened to a science fiction version of the U.S. Gold Rush of the nineteenth century.

“The cost of getting to the moon, creating a lunar base, extracting the minerals and getting them back to earth probably far outweighs mining precious minerals on the Earth,” he told Defense News in an interview.

It’s also still unclear exactly what types of rare-earth metals, critical in producing high-tech components, exist under the lunar surface. On Earth, China is a critical supplier of such ingredients. European and NATO nations are eager to diversify their supply chain as they view Beijing as an unreliable partner politically.

Godfrey characterized developments toward lunar mining as purely commercial, but, by raising the matter, made clear it has started to pop up on the radars of armed forces, with very practical questions emerging.

“Do you ring-fence your particular area on the moon if you strike gold, so to speak?” Godfrey asked.

Whether moon mining will become feasible one day depends on key technologies and ensured access to space for all, he said, adding that proliferating space debris could make the journey impossible for everyone at some point.

Reducing the cost of space launches and advancing the field of on-orbit manufacturing also are stepping stones to the vision of moon mining, Godfrey added.

About Sebastian Sprenger is associate editor for Europe at Defense News, reporting on the state of the defense market in the region, and on U.S.-Europe cooperation and multi-national investments in defense and global security. Previously he served as managing editor for Defense News. He is based in Cologne, Germany.

How private companies aiming for the Moon are ushering in a new age of space exploration

By Anna Desmarais

By Anna Desmarais

Published on 10/03/2024 -

The successful lunar mission by Intuitive Machines last month was in part subsidised by NASA - and it's only the beginning.

The successful but short Intuitive Machines Moon landing last month will be the first in a series of attempts by private companies in the United States from now until the end of the decade.

That’s the takeaway experts in the field want the general public to have from a historic venture cut short.

The mission fizzled out five days in because of a loss of power to the lunar lander Odysseus as the Sun moved away from the last illuminated solar panel on its back.

"This mission is a pathfinder," Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a press conference a few days into the mission. "You can think of it as a flight test".

That’s because the Intuitive Machines mission got part of their funding from a relatively new, little-known NASA programme called the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative. Its aim: putting the responsibility and technicalities of a Moon landing on to private companies for the first time.

Those in the industry say this new initiative from the Us space agency is starting a chain of frequent Moon launches that will define the US presence in space for the next decade as the country prepares for another human landing.

Nicholas Peter, the president of France’s International Space University (ISU) calls this new NASA programme the beginning of the US' "new race to the Moon," as they try to compete with recent successful landings from India, Japan, and China.

"[CLPS] is providing more opportunities to go to the Moon to develop scientific missions, now that it’s not restricted to government bodies," Peter told Euronews Next.

Intuitive Machines' lunar lander blasts off to the Moon in a historic attempt by a private company

NASA's new mission

On May 3, 2018, NASA released a bold new communiqué: that Moon surface exploration would continue in the future, but it would look different.

In the same breath, NASA announced its investment of $2.6 billion (€2.4 billion) to last until 2028 into indefinite contracts, bidded on by a select number of private companies, to "accelerate" the American return to the Moon.

"We’ll draw on the interests and capabilities of U.S. industry and international partners as American innovation leads astronauts back to the Moon and to destinations farther into the solar system, including Mars," said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a press release at the time.

February’s mission from Intuitive Machines is the most recent in a series of expected "deliverable" missions expected before 2026.

The mission is also the second under the CLPS program to get to launch.

In January, Pittsburg-based Astrobotic Technology launched the first and it failed because of a propellant leak that made it impossible to land. Other NASA-funded companies like Draper and Firefly Aerospace are working on upcoming missions.

Later this year, NASA expects mission VIPER from Astrobotic to the lunar south pole, a delivery of technology from Firefly Aerospace to a basaltic plain on the Moon, and another mission from Intuitive Machines to Reiner Gamma, a lunar swirl on the side of the Moon.

NASA declined an interview with Euronews Next.

Ingenuity: NASA's 'little helicopter that could' takes last flight on Mars

"There are companies [funded by NASA] that were barely in existence, were in their infancy that grew to mature companies that can provide this service," Boger said.

There’s other reasons to want to get back to the Moon, according to Peter from the International Space University. One is the new technologies, like data storage in deep space.

Another is the new frontier for resource extraction. The Moon has resources, like water and hydrogen that Peter says will become increasingly important on Earth.

"[Space exploration is] not about planting a flag anymore," Peter said, making reference to the goals of the 1969 Moon landing.

A relay, not a sprint to the Moon

Draper's mission in 2025 is to Schrodinger's Basin, a rare part of the Moon that shows recent volcanic activity (Boger wouldn’t specify how much NASA funding is going into their mission).

Boger said he was "ecstatic" for his colleagues at Intuitive Machines when he heard news of their successful soft landing.

He maintains that this modern space race is less a sprint, more a relay with alot of collaboration between all the companies leading launches.

"All of these missions are providing immense lessons learned for those that haven’t launched yet," Boger said.

"It’s a tight community, there’s alot of transparency and sharing information that we can factor into the mission objectives".

The successful lunar mission by Intuitive Machines last month was in part subsidised by NASA - and it's only the beginning.

The successful but short Intuitive Machines Moon landing last month will be the first in a series of attempts by private companies in the United States from now until the end of the decade.

That’s the takeaway experts in the field want the general public to have from a historic venture cut short.

The mission fizzled out five days in because of a loss of power to the lunar lander Odysseus as the Sun moved away from the last illuminated solar panel on its back.

"This mission is a pathfinder," Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a press conference a few days into the mission. "You can think of it as a flight test".

That’s because the Intuitive Machines mission got part of their funding from a relatively new, little-known NASA programme called the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative. Its aim: putting the responsibility and technicalities of a Moon landing on to private companies for the first time.

Those in the industry say this new initiative from the Us space agency is starting a chain of frequent Moon launches that will define the US presence in space for the next decade as the country prepares for another human landing.

Nicholas Peter, the president of France’s International Space University (ISU) calls this new NASA programme the beginning of the US' "new race to the Moon," as they try to compete with recent successful landings from India, Japan, and China.

"[CLPS] is providing more opportunities to go to the Moon to develop scientific missions, now that it’s not restricted to government bodies," Peter told Euronews Next.

Intuitive Machines' lunar lander blasts off to the Moon in a historic attempt by a private company

NASA's new mission

On May 3, 2018, NASA released a bold new communiqué: that Moon surface exploration would continue in the future, but it would look different.

In the same breath, NASA announced its investment of $2.6 billion (€2.4 billion) to last until 2028 into indefinite contracts, bidded on by a select number of private companies, to "accelerate" the American return to the Moon.

"We’ll draw on the interests and capabilities of U.S. industry and international partners as American innovation leads astronauts back to the Moon and to destinations farther into the solar system, including Mars," said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a press release at the time.

February’s mission from Intuitive Machines is the most recent in a series of expected "deliverable" missions expected before 2026.

The mission is also the second under the CLPS program to get to launch.

In January, Pittsburg-based Astrobotic Technology launched the first and it failed because of a propellant leak that made it impossible to land. Other NASA-funded companies like Draper and Firefly Aerospace are working on upcoming missions.

Later this year, NASA expects mission VIPER from Astrobotic to the lunar south pole, a delivery of technology from Firefly Aerospace to a basaltic plain on the Moon, and another mission from Intuitive Machines to Reiner Gamma, a lunar swirl on the side of the Moon.

NASA declined an interview with Euronews Next.

'It’s not about planting a flag anymore'

Chris Boger, Draper’s Director of Human Space Flight and Exploration, said that before NASA's new CLPS program, it was rare to find an entire space mission by a private company that was supported by the government.

Instead, the space agency would give private companies the task of developing one part of the spacecraft’s hardwire. For Draper, their first NASA contract came in 1959 to develop the navigation system for the famous Apollo landing.

Recently, Boger said there’s been a renewed "explosion" of commercial interest to get to the Moon. So, he continues, that gives NASA more incentive to "boot strap" more missions and, by extension, creating a healthier space startup space.

Chris Boger, Draper’s Director of Human Space Flight and Exploration, said that before NASA's new CLPS program, it was rare to find an entire space mission by a private company that was supported by the government.

Instead, the space agency would give private companies the task of developing one part of the spacecraft’s hardwire. For Draper, their first NASA contract came in 1959 to develop the navigation system for the famous Apollo landing.

Recently, Boger said there’s been a renewed "explosion" of commercial interest to get to the Moon. So, he continues, that gives NASA more incentive to "boot strap" more missions and, by extension, creating a healthier space startup space.

Ingenuity: NASA's 'little helicopter that could' takes last flight on Mars

"There are companies [funded by NASA] that were barely in existence, were in their infancy that grew to mature companies that can provide this service," Boger said.

There’s other reasons to want to get back to the Moon, according to Peter from the International Space University. One is the new technologies, like data storage in deep space.

Another is the new frontier for resource extraction. The Moon has resources, like water and hydrogen that Peter says will become increasingly important on Earth.

"[Space exploration is] not about planting a flag anymore," Peter said, making reference to the goals of the 1969 Moon landing.

A relay, not a sprint to the Moon

Draper's mission in 2025 is to Schrodinger's Basin, a rare part of the Moon that shows recent volcanic activity (Boger wouldn’t specify how much NASA funding is going into their mission).

Boger said he was "ecstatic" for his colleagues at Intuitive Machines when he heard news of their successful soft landing.

He maintains that this modern space race is less a sprint, more a relay with alot of collaboration between all the companies leading launches.

"All of these missions are providing immense lessons learned for those that haven’t launched yet," Boger said.

"It’s a tight community, there’s alot of transparency and sharing information that we can factor into the mission objectives".

More missions to the Moon mean more chances for values, cultures, and priorities to collide.

BYKIONA SMITH

MARCH 6, 2024

INVERSE

Afew weeks before he died, President William G. Harding toured Yellowstone National Park. He said bluntly, “Commercialism will never be tolerated here as long as I have the power to prevent it.” The U.S. National Park system exists, in part, to protect some of our country’s most pristine wilderness from being destroyed by ventures like construction, mining, and logging.

While we’ve been able to create National Parks here in the U.S., nobody has the legal right to do that on the Moon. So what happens to the once-pristine Moon when the space miners show up?

Along with private missions like the recent Intuitive Machines’ lander IM-1, several countries’ space agencies all have their eyes on the same real estate around the Moon’s south pole, where water ice may lie waiting in permanently shadowed craters. Until recently, debates about what should and shouldn’t happen on the Moon have been abstract. Only one country’s space agency had ever sent humans to the Moon, and they didn’t stay long. That’s on the brink of changing. The next decade may see the once-pristine lunar landscape dotted with bases and riddled with mines, all jostling for space (and bandwidth) with telescopes and other scientific exploration. But is the lunar environment worth preserving, for science or in its own right, and who gets to decide?

There’s no life on the Moon, but the scenery is breathtaking (astronaut Harrison Schmitt for scale).NASA

WHO OWNS THE MOON?

A recent (failed) mission to land cremated human remains on the Moon raised a high-profile example of the kind of ethical issues space ethicists say we should be considering. Astrobotic’s Peregrine One lander was scheduled to deliver the cremated remains of Gene Roddenberry and several members of the original Star Trek cast, and others to the Moon.

The Navajo Nation formally protested the mission’s launch; in Navajo beliefs, the Moon is a sacred object, and placing human remains there would be a desecration. In the end, a fuel leak forced the mission to return to Earth, where it ended in a fiery plunge into the upper atmosphere, but it drew attention to a larger debate about who gets to decide — for everyone — how we as a species relate to the Moon now.

“Every culture on Earth has conceptions about the Moon,” Santa Clara University space ethicist Brian Green tells Inverse. “There are lots of groups on Earth who have thoughts on how the Moon should be treated. This is why we need to have a larger conversation.”

Part of the unfolding discussion centers on what, if anything, we should try to protect on the Moon. Several groups here on Earth, such as For All Moonkind, have spent years arguing that the first crewed lunar landing sites are an important part of human history and should be preserved, but at the moment there’s no law or treaty preventing someone from erasing the rover tracks or astronauts’ footprints.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module casts a long shadow over the surface of the Moon — and the footprints of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — in July 1968.NASA

The Navajo aren't the only people who consider the Moon sacred. Cultures around the world have always tended to connect the Moon with the divine. For Hindus, the Moon represents the god Chandra, who is associated with plants and the night. Shinto believers see the Moon as the god Tsukuyomi, and for the Inuit, it's Alignak, a god whose domain includes weather, tides, and earthquakes. In ancient times, the Greeks worshiped the virginal huntress and nature goddess Artemis, while the Egyptians worshiped the god Khonsu, a healer and protector of nighttime travelers.

These deities' domains reveal a lot about how people have seen the moon over the millennia. It's been something pure, a bright light in the darkness, sometimes protective but other times belonging more to wild things than to people.

But the Moon is also a place; in the late 1500s, Galileo pointed his early telescopes at the Moon and discovered mountains, valleys, and craters. Today, we know the Moon as a dusty landscape marked by ancient volcanoes and billions of years of meteors. We've crashed spacecraft into its surface (both accidentally and on purpose), a few people have walked and even driven around small parts of it, and most of them left behind bags of waste and piles of dead-weight junk. But most of the Moon is still what astrophysicist and space ethicist Erika Nesvold calls a “space wilderness." She acknowledges that it's hard to think of wilderness in a place with no life, but argues that perhaps we should.

“We also have to ask questions about things like resource overuse,” says Nesvold. “If we mine out all the water on the moon in the next three generations, what are future generations going to do? Do we need to make sure we're preserving any of that?”

Increasingly, national governments and private companies are seeing the Moon not as a deity, a symbol, or a scientific puzzle: they're beginning to see it as a resource: a source of fuel and water on the way to Mars, a site for radio telescopes, or a source of geopolitical clout.

And that's sparking an urgent debate about whether some parts of the Moon remain pristine -- and if so, which parts. Whose faith and traditions, whose scientific curiosity, whose sense of aesthetics, or whose billion-dollar business plan should decide the fate of the Moon's ancient landscape?

China is the Unites States’ main competitor in the current “space race,” with India close behind.FUTURE PUBLISHING/FUTURE PUBLISHING/GETTY IMAGES

IF YOU’RE NOT FIRST, YOU’RE LAST

Part of the challenge of “space ethics” is to figure out what to do about these issues, but the really difficult part will be figuring out who gets to have a say. Can anyone tell a private company where, or whether, they can mine the Moon, open a lunar landfill, or turn a crater into a cemetery? How can countries with wildly differing values agree on the value – commercial, scientific, or ideological – of the Moon?

“At the more international level, that’s what international law is for,” says Nesvold.

At the moment, only the absolute basics are covered, starting with the Outer Space Treaty, in which most of the world’s nations have agreed that no one can claim territory in space, the Moon is to be used only for peaceful purposes, and nuclear weapons aren’t allowed in space. The Registration Convention requires states to register the orbital paths of their spacecraft with the UN to help prevent collisions. And the Rescue Agreement requires states to help spacefarers in distress, regardless of where they’re from.

Another treaty, the Space Liability Convention, says that spacecraft are the responsibility of the country they’re launched from — whether they’re publicly or privately owned. That means it’s up to an individual country to decide whether a company can launch human remains, soda cans, tardigrades, or anything else to the Moon (under U.S. regulations, any payload can go as long as it’s safe to launch and not a threat to national security).

What’s not covered by those laws is whether it’s okay to carve a giant advertising logo into a lunar basin, inter human remains or leave branded trinkets on the Moon, mine iconic lunar landmarks, or send tourists to the Apollo 11 landing site to walk in Neil Armstrong’s footsteps. And those are all very real possibilities in the near future. Space law, and space ethics, are urgent works in progress.

This artist’s illustration shows what future construction projects on the Moon might look like.NASA

Meanwhile, the power to make those decisions is a big reason countries like the U.S., China, India, and Russia are all scrambling to get a foothold on the lunar surface before their rivals. Being the first to set up shop on the Moon is a huge way for a nation to show off its power, wealth, and technological chops. But on a practical level, being first also means first pick of landing sites, first dibs on lunar resources, and the first chance to choose which pieces of the lunar environment to protect.

“Ultimately, the people who get to make the decisions are the ones who are there,” says Green. “So that's why you hope that the people who are making the decisions and who are there are going to be ethical and actually considerate of other people's opinions.”

But that space race mentality can have its own problems.

“The space race dynamic always makes ethics more complicated,” says Green.

For one thing, there’s the question of what ethical shortcuts a nation or company might be willing to take to get there first. That could mean exploiting workers, taking undue risks with astronauts, or damaging the environment here on Earth.

“People who are arguing for more space telescopes, or people who are arguing for space launch centers on the path towards settling space often have really noble-sounding rhetoric: The idea of rocket launches and building more human civilization in space, versus the concerns about potential pollutants in local wetlands – the sorts of things you hear about in places like Boca Chica,” Nesvold tells Inverse. “I think that's very similar to the sort of manifest destiny rhetoric that you would see during colonization.”

Humans will go to great lengths to plant their country’s flag.NASA

America’s crewed space program was built on a major ethical shortcut: the work of Nazi officer Werner von Braun, who also designed the V2 rockets that killed around 9,000 British civilians during World War II (thousands more forced laborers died building them). Operation Paperclip, which brought von Braun and his team of engineers to the U.S., might have been unthinkable without the pressure to stay ahead of the USSR in space.

What space ethicists like Green and Nesvold want to avoid is a future where we plow blindly forward, with whoever gets there first imposing their will on a satellite that has, for all of human history until now, belonged to everyone – but at the same time, to no one. Nesvold warns that if we do that, we risk repeating the injustices of colonialism here on Earth.

IS ANTARCTICA A BLUEPRINT FOR SPACE?

Nations whose interests and values often clash will have to agree on how to manage a commons: "a broad set of resources, natural and cultural, that are shared by many people," as the International Association for the Study of the Commons puts it. We've already done that here on Earth, to some extent. The future of the Moon and Mars may owe a lot to the system of treaties that protect Antarctica and the set of laws that apply in international waters.

The international agreements that protect these adorable penguins could provide a framework for cooperation on the Moon.ANADOLU/ANADOLU/GETTY IMAGES

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty reserves the entire Antarctic continent for peaceful, scientific use. No commercial mining is allowed, and there are strict rules protecting plants, wildlife, and landscapes. Tourists, scientists, and even some military personnel are allowed to visit (or live there for months at a stretch), but only if the expedition or tour operator has a permit from one of the 56 countries that have signed the treaty.

Countries that issue permits have regulations about the type of activity and the number of people they'll allow; some of those rules are to protect the fragile polar environment, but others are for safety. For example, "the UK will also not normally authorize the use of helicopters for recreational purposes in areas with concentrations of wildlife, including the Antarctic Peninsula region." (As a side note, "for safety reasons the UK will not authorize snorkeling activities in the Antarctic." The more you know.)

Eight of the countries who signed the treaty claim sectors of territory in Antarctica, and some of them overlap. In theory, no one is allowed to claim new territory in Antarctica; the eight countries that claim sectors today had already made their claims before the Antarctic Treaty was written, and part of the treaty forbids anyone from making new claims. But both the U.S. and Russia argue that they've reserved the right to claim territory in Antarctica in the future.

On the other hand, several countries, including the U.S., have research stations in other countries' sectors without any major conflict.

If someone wants to violate the Antarctic Treaty, it's going to be hard to stop them without resorting to military force. That's even more true on the Moon. But so far, the Antarctic Treaty has worked fairly well.

"If we can look at what's worked and what hasn't in terms of preventing conflicts and protecting the environment, then we can apply those in space," says Nesvold.

Afew weeks before he died, President William G. Harding toured Yellowstone National Park. He said bluntly, “Commercialism will never be tolerated here as long as I have the power to prevent it.” The U.S. National Park system exists, in part, to protect some of our country’s most pristine wilderness from being destroyed by ventures like construction, mining, and logging.

While we’ve been able to create National Parks here in the U.S., nobody has the legal right to do that on the Moon. So what happens to the once-pristine Moon when the space miners show up?

Along with private missions like the recent Intuitive Machines’ lander IM-1, several countries’ space agencies all have their eyes on the same real estate around the Moon’s south pole, where water ice may lie waiting in permanently shadowed craters. Until recently, debates about what should and shouldn’t happen on the Moon have been abstract. Only one country’s space agency had ever sent humans to the Moon, and they didn’t stay long. That’s on the brink of changing. The next decade may see the once-pristine lunar landscape dotted with bases and riddled with mines, all jostling for space (and bandwidth) with telescopes and other scientific exploration. But is the lunar environment worth preserving, for science or in its own right, and who gets to decide?

There’s no life on the Moon, but the scenery is breathtaking (astronaut Harrison Schmitt for scale).NASA

WHO OWNS THE MOON?

A recent (failed) mission to land cremated human remains on the Moon raised a high-profile example of the kind of ethical issues space ethicists say we should be considering. Astrobotic’s Peregrine One lander was scheduled to deliver the cremated remains of Gene Roddenberry and several members of the original Star Trek cast, and others to the Moon.

The Navajo Nation formally protested the mission’s launch; in Navajo beliefs, the Moon is a sacred object, and placing human remains there would be a desecration. In the end, a fuel leak forced the mission to return to Earth, where it ended in a fiery plunge into the upper atmosphere, but it drew attention to a larger debate about who gets to decide — for everyone — how we as a species relate to the Moon now.

“Every culture on Earth has conceptions about the Moon,” Santa Clara University space ethicist Brian Green tells Inverse. “There are lots of groups on Earth who have thoughts on how the Moon should be treated. This is why we need to have a larger conversation.”

Part of the unfolding discussion centers on what, if anything, we should try to protect on the Moon. Several groups here on Earth, such as For All Moonkind, have spent years arguing that the first crewed lunar landing sites are an important part of human history and should be preserved, but at the moment there’s no law or treaty preventing someone from erasing the rover tracks or astronauts’ footprints.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module casts a long shadow over the surface of the Moon — and the footprints of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — in July 1968.NASA

The Navajo aren't the only people who consider the Moon sacred. Cultures around the world have always tended to connect the Moon with the divine. For Hindus, the Moon represents the god Chandra, who is associated with plants and the night. Shinto believers see the Moon as the god Tsukuyomi, and for the Inuit, it's Alignak, a god whose domain includes weather, tides, and earthquakes. In ancient times, the Greeks worshiped the virginal huntress and nature goddess Artemis, while the Egyptians worshiped the god Khonsu, a healer and protector of nighttime travelers.

These deities' domains reveal a lot about how people have seen the moon over the millennia. It's been something pure, a bright light in the darkness, sometimes protective but other times belonging more to wild things than to people.

But the Moon is also a place; in the late 1500s, Galileo pointed his early telescopes at the Moon and discovered mountains, valleys, and craters. Today, we know the Moon as a dusty landscape marked by ancient volcanoes and billions of years of meteors. We've crashed spacecraft into its surface (both accidentally and on purpose), a few people have walked and even driven around small parts of it, and most of them left behind bags of waste and piles of dead-weight junk. But most of the Moon is still what astrophysicist and space ethicist Erika Nesvold calls a “space wilderness." She acknowledges that it's hard to think of wilderness in a place with no life, but argues that perhaps we should.

“We also have to ask questions about things like resource overuse,” says Nesvold. “If we mine out all the water on the moon in the next three generations, what are future generations going to do? Do we need to make sure we're preserving any of that?”

Increasingly, national governments and private companies are seeing the Moon not as a deity, a symbol, or a scientific puzzle: they're beginning to see it as a resource: a source of fuel and water on the way to Mars, a site for radio telescopes, or a source of geopolitical clout.

And that's sparking an urgent debate about whether some parts of the Moon remain pristine -- and if so, which parts. Whose faith and traditions, whose scientific curiosity, whose sense of aesthetics, or whose billion-dollar business plan should decide the fate of the Moon's ancient landscape?

China is the Unites States’ main competitor in the current “space race,” with India close behind.FUTURE PUBLISHING/FUTURE PUBLISHING/GETTY IMAGES

IF YOU’RE NOT FIRST, YOU’RE LAST

Part of the challenge of “space ethics” is to figure out what to do about these issues, but the really difficult part will be figuring out who gets to have a say. Can anyone tell a private company where, or whether, they can mine the Moon, open a lunar landfill, or turn a crater into a cemetery? How can countries with wildly differing values agree on the value – commercial, scientific, or ideological – of the Moon?

“At the more international level, that’s what international law is for,” says Nesvold.

At the moment, only the absolute basics are covered, starting with the Outer Space Treaty, in which most of the world’s nations have agreed that no one can claim territory in space, the Moon is to be used only for peaceful purposes, and nuclear weapons aren’t allowed in space. The Registration Convention requires states to register the orbital paths of their spacecraft with the UN to help prevent collisions. And the Rescue Agreement requires states to help spacefarers in distress, regardless of where they’re from.

Another treaty, the Space Liability Convention, says that spacecraft are the responsibility of the country they’re launched from — whether they’re publicly or privately owned. That means it’s up to an individual country to decide whether a company can launch human remains, soda cans, tardigrades, or anything else to the Moon (under U.S. regulations, any payload can go as long as it’s safe to launch and not a threat to national security).

What’s not covered by those laws is whether it’s okay to carve a giant advertising logo into a lunar basin, inter human remains or leave branded trinkets on the Moon, mine iconic lunar landmarks, or send tourists to the Apollo 11 landing site to walk in Neil Armstrong’s footsteps. And those are all very real possibilities in the near future. Space law, and space ethics, are urgent works in progress.

This artist’s illustration shows what future construction projects on the Moon might look like.NASA

Meanwhile, the power to make those decisions is a big reason countries like the U.S., China, India, and Russia are all scrambling to get a foothold on the lunar surface before their rivals. Being the first to set up shop on the Moon is a huge way for a nation to show off its power, wealth, and technological chops. But on a practical level, being first also means first pick of landing sites, first dibs on lunar resources, and the first chance to choose which pieces of the lunar environment to protect.

“Ultimately, the people who get to make the decisions are the ones who are there,” says Green. “So that's why you hope that the people who are making the decisions and who are there are going to be ethical and actually considerate of other people's opinions.”

But that space race mentality can have its own problems.

“The space race dynamic always makes ethics more complicated,” says Green.

For one thing, there’s the question of what ethical shortcuts a nation or company might be willing to take to get there first. That could mean exploiting workers, taking undue risks with astronauts, or damaging the environment here on Earth.

“People who are arguing for more space telescopes, or people who are arguing for space launch centers on the path towards settling space often have really noble-sounding rhetoric: The idea of rocket launches and building more human civilization in space, versus the concerns about potential pollutants in local wetlands – the sorts of things you hear about in places like Boca Chica,” Nesvold tells Inverse. “I think that's very similar to the sort of manifest destiny rhetoric that you would see during colonization.”

Humans will go to great lengths to plant their country’s flag.NASA

America’s crewed space program was built on a major ethical shortcut: the work of Nazi officer Werner von Braun, who also designed the V2 rockets that killed around 9,000 British civilians during World War II (thousands more forced laborers died building them). Operation Paperclip, which brought von Braun and his team of engineers to the U.S., might have been unthinkable without the pressure to stay ahead of the USSR in space.

What space ethicists like Green and Nesvold want to avoid is a future where we plow blindly forward, with whoever gets there first imposing their will on a satellite that has, for all of human history until now, belonged to everyone – but at the same time, to no one. Nesvold warns that if we do that, we risk repeating the injustices of colonialism here on Earth.

IS ANTARCTICA A BLUEPRINT FOR SPACE?

Nations whose interests and values often clash will have to agree on how to manage a commons: "a broad set of resources, natural and cultural, that are shared by many people," as the International Association for the Study of the Commons puts it. We've already done that here on Earth, to some extent. The future of the Moon and Mars may owe a lot to the system of treaties that protect Antarctica and the set of laws that apply in international waters.

The international agreements that protect these adorable penguins could provide a framework for cooperation on the Moon.ANADOLU/ANADOLU/GETTY IMAGES

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty reserves the entire Antarctic continent for peaceful, scientific use. No commercial mining is allowed, and there are strict rules protecting plants, wildlife, and landscapes. Tourists, scientists, and even some military personnel are allowed to visit (or live there for months at a stretch), but only if the expedition or tour operator has a permit from one of the 56 countries that have signed the treaty.

Countries that issue permits have regulations about the type of activity and the number of people they'll allow; some of those rules are to protect the fragile polar environment, but others are for safety. For example, "the UK will also not normally authorize the use of helicopters for recreational purposes in areas with concentrations of wildlife, including the Antarctic Peninsula region." (As a side note, "for safety reasons the UK will not authorize snorkeling activities in the Antarctic." The more you know.)

Eight of the countries who signed the treaty claim sectors of territory in Antarctica, and some of them overlap. In theory, no one is allowed to claim new territory in Antarctica; the eight countries that claim sectors today had already made their claims before the Antarctic Treaty was written, and part of the treaty forbids anyone from making new claims. But both the U.S. and Russia argue that they've reserved the right to claim territory in Antarctica in the future.

On the other hand, several countries, including the U.S., have research stations in other countries' sectors without any major conflict.

If someone wants to violate the Antarctic Treaty, it's going to be hard to stop them without resorting to military force. That's even more true on the Moon. But so far, the Antarctic Treaty has worked fairly well.

"If we can look at what's worked and what hasn't in terms of preventing conflicts and protecting the environment, then we can apply those in space," says Nesvold.

No comments:

Post a Comment