‘Mystery of Cleopatra’ exhibit in Paris pushes back against clichés

For centuries, depictions of Cleopatra have emphasised her beauty and romantic entanglements – much more so than her two-decade rule of Egypt. The Institut du monde arabe (Arab World Institute) in Paris aims to change that with “The Mystery of Cleopatra”, a new exhibit running until January 11, 2026.

Issued on: 26/06/2025 - FRANCE24

By: Vitoria Barreto

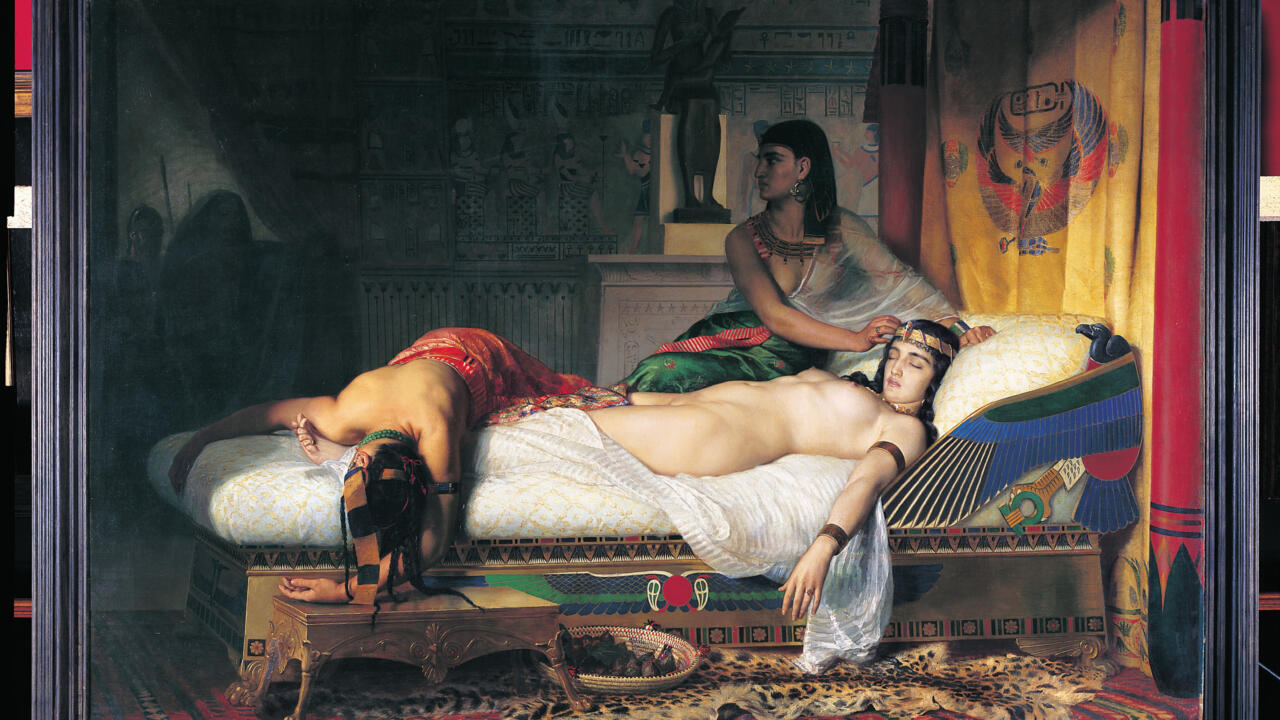

"The Death of Cleopatra", oil on canvas, Toulouse, Musée des Augustins, 1874.

© Jean-André Rixens

Cleopatra has become an icon throughout the centuries, depicted in both classical art and pop culture as a strategic seductress who had relationships with Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, overshadowing her role as a head of state.

“The Mystery of Cleopatra” exhibit at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris, on view until January 11, 2026, aims to push back on these clichés. It opens with archaeological and historical information about her reign, then shifts to explore how the myth of her was constructed through cinema and contemporary art – and, ultimately, how Cleopatra is being reimagined as a symbol of resistance.

A 17th-century white marble statue of Cleopatra, standing tall with a snake wrapped around her body, is the first element a visitor encounters, which sets the tone for the rest of the show.

Cleopatra has become an icon throughout the centuries, depicted in both classical art and pop culture as a strategic seductress who had relationships with Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, overshadowing her role as a head of state.

“The Mystery of Cleopatra” exhibit at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris, on view until January 11, 2026, aims to push back on these clichés. It opens with archaeological and historical information about her reign, then shifts to explore how the myth of her was constructed through cinema and contemporary art – and, ultimately, how Cleopatra is being reimagined as a symbol of resistance.

A 17th-century white marble statue of Cleopatra, standing tall with a snake wrapped around her body, is the first element a visitor encounters, which sets the tone for the rest of the show.

Cleopatra dying, standing, 17th century Versailles, châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. © Château de Versailles, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn, Didier Saulnier

Exhibit curator Claude Mollard points out that from the 15th century onwards, Cleopatra was presented as a seductress. Even Cleopatra’s death has been sexualized. But he says artists have also long been fascinated by her as a symbol of freedom and defiance: she ultimately chooses death over submission. “She is a free woman,” he says.

Cleopatra “preferred to kill herself rather than submit to Octavian, who wanted to take her prisoner and present her in Rome as evidence of his triumph and then, perhaps, execute her".

Born in Alexandria around 69 BCE, Cleopatra was both Greek and Egyptian – a descendant of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since 305 BCE.

Watch moreIn Paris, a museum displays "rescued treasures from Gaza"

Mollard describes Cleopatra's Alexandria as a relatively tolerant regime where multiple religions coexisted and ethnic groups governed themselves through their own courts.

“The Jews had their courts, the Greeks had their courts, and the Egyptians had their courts,” he says. “It was hyper modern, hyper tolerant."

Burial urns and figurines of deities from the time included in the exhibition depict the juxtaposition of religions living in relative harmony.

Egypt’s political structure at the time was unique: men and women often ruled together, often through symbolic sibling marriages, as was the case with Cleopatra and her brother, whom she eventually displaced with Caesar’s support.

Following Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra allied herself with Marc Antony, continuing Egypt’s co-sovereign tradition within the Roman political framework. But as Octavian moved to consolidate Rome under his rule, Cleopatra and Antony resisted, eventually committing suicide after Octavian defeated their forces. Their deaths marked not just the end of a dynasty, but the fall of an entire system of governance.

“The death of Cleopatra marks the end of a tolerant, mixed way of governing and its replacement by a paternalistic male government, which would spread throughout Europe all the way to General [Charles] de Gaulle” and even the conflicts of today, says Mollard.

With Octavian’s victory, the Roman patriarchal regime expanded across Egypt and the Middle East. But Cleopatra’s legacy endured. Coins bearing her face – the only evidence we have of what she looked like –remained in circulation and were cherished by Egyptians for more than 150 years.

Exhibit curator Claude Mollard points out that from the 15th century onwards, Cleopatra was presented as a seductress. Even Cleopatra’s death has been sexualized. But he says artists have also long been fascinated by her as a symbol of freedom and defiance: she ultimately chooses death over submission. “She is a free woman,” he says.

Cleopatra “preferred to kill herself rather than submit to Octavian, who wanted to take her prisoner and present her in Rome as evidence of his triumph and then, perhaps, execute her".

Born in Alexandria around 69 BCE, Cleopatra was both Greek and Egyptian – a descendant of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since 305 BCE.

Watch moreIn Paris, a museum displays "rescued treasures from Gaza"

Mollard describes Cleopatra's Alexandria as a relatively tolerant regime where multiple religions coexisted and ethnic groups governed themselves through their own courts.

“The Jews had their courts, the Greeks had their courts, and the Egyptians had their courts,” he says. “It was hyper modern, hyper tolerant."

Burial urns and figurines of deities from the time included in the exhibition depict the juxtaposition of religions living in relative harmony.

Egypt’s political structure at the time was unique: men and women often ruled together, often through symbolic sibling marriages, as was the case with Cleopatra and her brother, whom she eventually displaced with Caesar’s support.

Following Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra allied herself with Marc Antony, continuing Egypt’s co-sovereign tradition within the Roman political framework. But as Octavian moved to consolidate Rome under his rule, Cleopatra and Antony resisted, eventually committing suicide after Octavian defeated their forces. Their deaths marked not just the end of a dynasty, but the fall of an entire system of governance.

“The death of Cleopatra marks the end of a tolerant, mixed way of governing and its replacement by a paternalistic male government, which would spread throughout Europe all the way to General [Charles] de Gaulle” and even the conflicts of today, says Mollard.

With Octavian’s victory, the Roman patriarchal regime expanded across Egypt and the Middle East. But Cleopatra’s legacy endured. Coins bearing her face – the only evidence we have of what she looked like –remained in circulation and were cherished by Egyptians for more than 150 years.

Coin of Cleopatra VII, made in Alexandria (Egypt).

© National Library of France, Paris, Department of Coins, Medals and Antiques

Sexualization of a queen

In the second part of the exhibition, both Roman and Arabic texts discuss how Cleopatra’s image has been shaped throughout time.

At the entrance to this section, a wall of sculpted noses is a reference to French physicist Blaise Pascal’s quote: “The nose of Cleopatra: if it had been shorter, the whole face of the earth would have changed.” Pascal’s attribution of the reasons for the Egyptian queen’s influence to a single facial feature illustrates how Western narratives often objectified her, erasing her political legacy.

"About 2 inches long", 2020 (production 2025). © Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos

These reductive portrayals date from Ancient Rome, when Octavian spread rumours about his erstwhile competitor by calling her a “prostitute queen”. Roman society followed suit, and coins bearing her image were vandalised.

Roman poets including Horace, Virgil and Propertius celebrated the defeat of the last Hellenistic queen in their poems, with Propertius deriding her as a whore-queen who dared to usurp masculine authority.

The exhibit suggests that Arabic thinkers held a different view of Cleopatra. Historian Ibn Abd al-Hakam (803-871 AD) described her as a "builder queen concerned with ensuring the safety and well-being of her people” even crediting her with the construction of the legendary Lighthouse of Alexandria.

The exhibit’s final section looks at what modern art and pop culture has made of Cleopatra.

These reductive portrayals date from Ancient Rome, when Octavian spread rumours about his erstwhile competitor by calling her a “prostitute queen”. Roman society followed suit, and coins bearing her image were vandalised.

Roman poets including Horace, Virgil and Propertius celebrated the defeat of the last Hellenistic queen in their poems, with Propertius deriding her as a whore-queen who dared to usurp masculine authority.

The exhibit suggests that Arabic thinkers held a different view of Cleopatra. Historian Ibn Abd al-Hakam (803-871 AD) described her as a "builder queen concerned with ensuring the safety and well-being of her people” even crediting her with the construction of the legendary Lighthouse of Alexandria.

The exhibit’s final section looks at what modern art and pop culture has made of Cleopatra.

From myth to symbol of resistance

Renaissance portrayals of the death of Cleopatra fill a section of the exhibition, leading visitors to a dark room with a screen showing how cinema has told Cleopatra’s story over time.

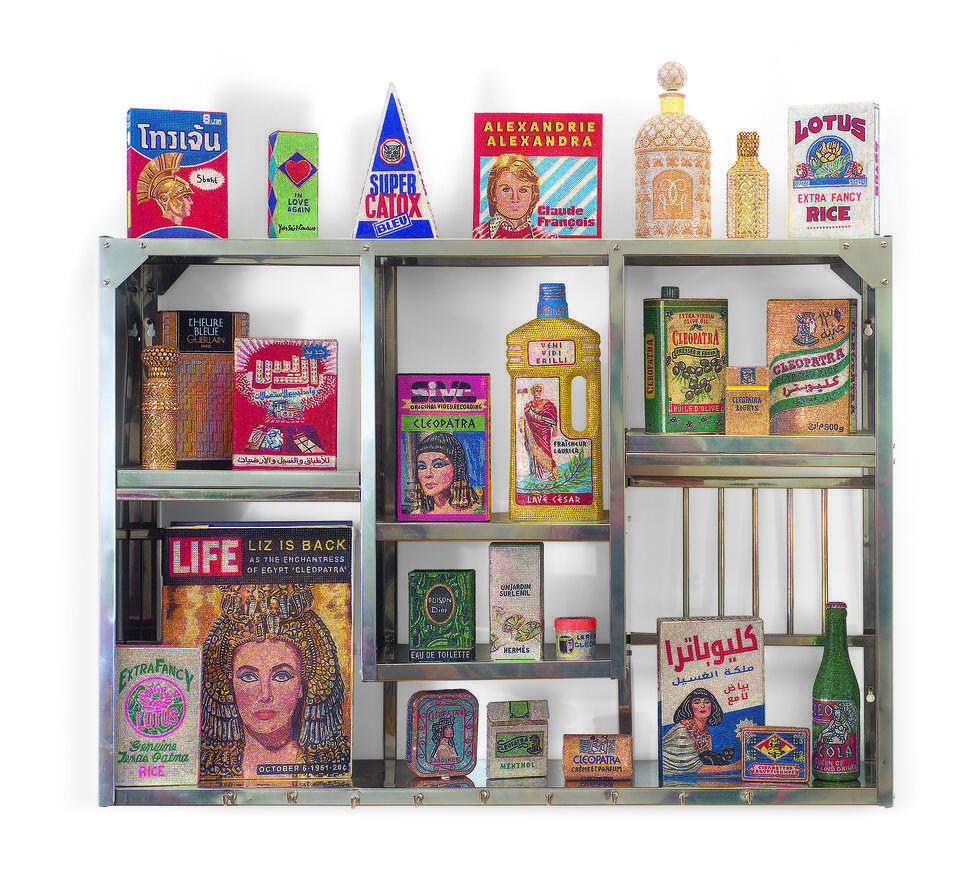

Cleopatra costumes, from Monica Bellucci’s in "Asterix & Obelix: Mission Cleopatra" to Elizabeth Taylor’s iconic performance, fill the room. Elements from commercials and consumer goods that commodify the queen’s image are also on display.

"Cleopatra's Kiosk", Shourouk Rhaiem, 2025. © Collection of the artist Alberto Ricci

These final rooms present her as a symbol of both feminist and colonial resistance. She became a symbol of anti‑colonial defiance during British rule of Egypt and she inspired African‑American pride during and after the Civil War in the United States.

Contemporary feminist artists also contribute to this reframing, exposing the deep misogyny of the way Cleopatra has been portrayed throughout history. One installation revisits ancient texts that once vilified her, now marked in red and rewritten.

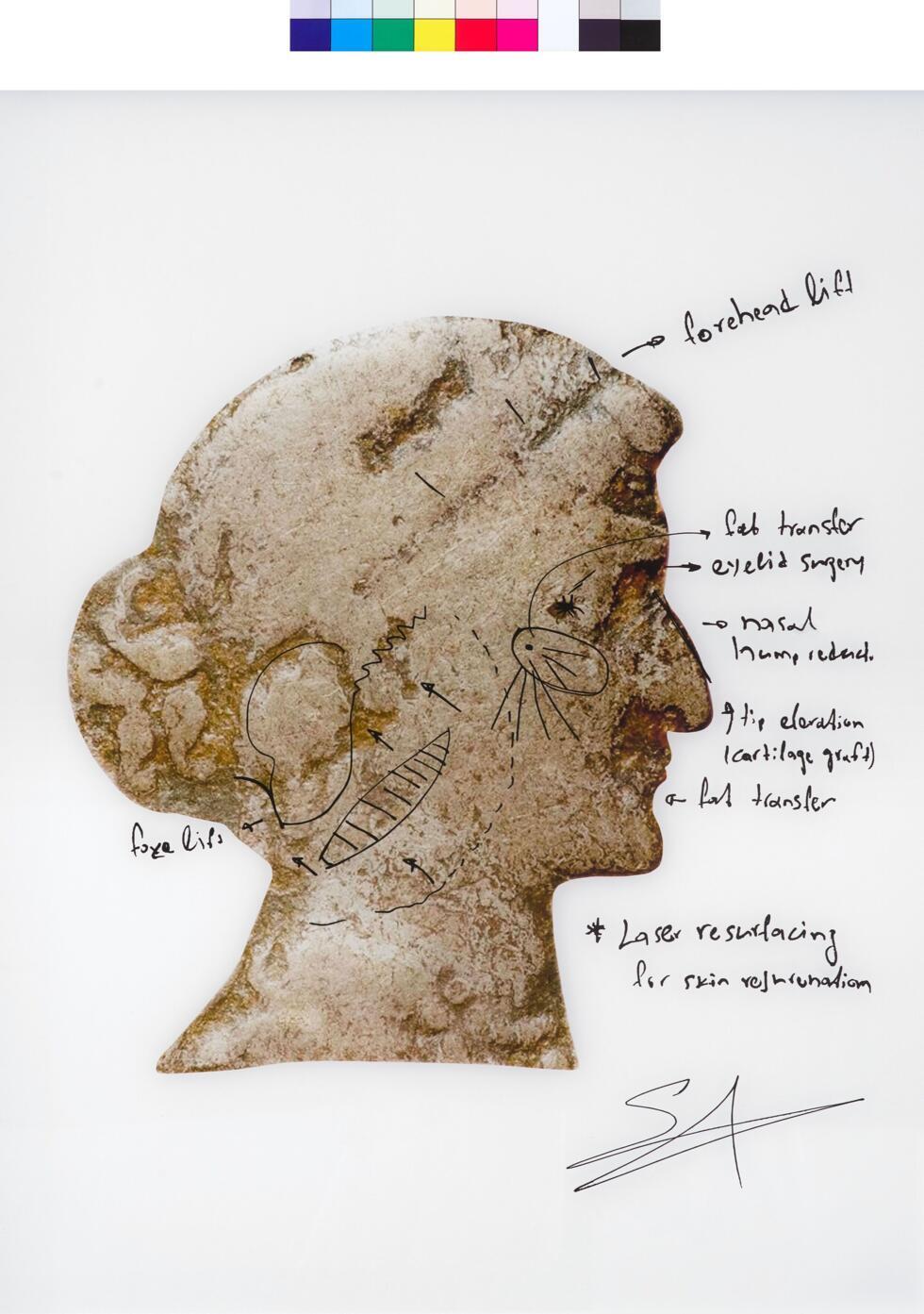

One of the most striking final pieces is a coin depicting her profile that includes notations of the cosmetic procedures Cleopatra would have to undergo to meet modern-day beauty standards.

These final rooms present her as a symbol of both feminist and colonial resistance. She became a symbol of anti‑colonial defiance during British rule of Egypt and she inspired African‑American pride during and after the Civil War in the United States.

Contemporary feminist artists also contribute to this reframing, exposing the deep misogyny of the way Cleopatra has been portrayed throughout history. One installation revisits ancient texts that once vilified her, now marked in red and rewritten.

One of the most striking final pieces is a coin depicting her profile that includes notations of the cosmetic procedures Cleopatra would have to undergo to meet modern-day beauty standards.

"I want to look like Cleopatra #1", 2020. © Esmeralda Komatopoulos

“Cleopatra is a feminist woman who resists the obstacles the Romans place in her path. And so, she has become an example, especially today, when we live in an international period in which the use of brute force is increasing every day," Mollard says.

“Cleopatra is a feminist woman who resists the obstacles the Romans place in her path. And so, she has become an example, especially today, when we live in an international period in which the use of brute force is increasing every day," Mollard says.

No comments:

Post a Comment