Revealed: The Mysterious, Legendary Giant Squid’s Genome

How did the monstrous giant squid – reaching school-bus size, with eyes as big as dinner plates and tentacles that can snatch prey 10 yards away – get so scarily big?

Today, important clues about the anatomy and evolution of the mysterious giant squid (Architeuthis dux) are revealed through publication of its full genome sequence by a University of Copenhagen-led team that includes scientist Caroline Albertin of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole.

Giant squid are rarely sighted and have never been caught and kept alive, meaning their biology (even how they reproduce) is still largely a mystery. The genome sequence can provide important insight.

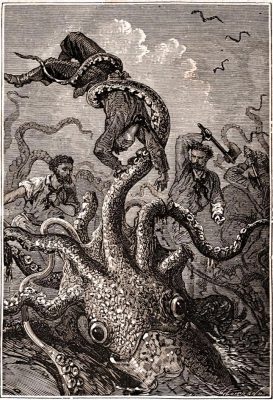

The giant squid has long been a subject of horror lore. In this original illustration from Jules Verne’s ‘20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,’ a giant squid grasps a helpless sailor. Credit: Alphonse de Neuville

“In terms of their genes, we found the giant squid look a lot like other animals. This means we can study these truly bizarre animals to learn more about ourselves,” says Albertin, who in 2015 led the team that sequenced the first genome of a cephalopod (the group that includes squid, octopus, cuttlefish, and nautilus).

Led by Rute da Fonseca at University of Copenhagen, the team discovered that the giant squid genome is big: with an estimated 2.7 billion DNA base pairs, it’s about 90 percent the size of the human genome.

Albertin analyzed several ancient, well-known gene families in the giant squid, drawing comparisons with the four other cephalopod species that have been sequenced and with the human genome.

She found that important developmental genes in almost all animals (Hox and Wnt) were present in single copies only in the giant squid genome. That means this gigantic, invertebrate creature – long a source of sea-monster lore – did NOT get so big through whole-genome duplication, a strategy that evolution took long ago to increase the size of vertebrates.

So, knowing how this squid species got so giant awaits further probing of its genome.

“A genome is a first step for answering a lot of questions about the biology of these very weird animals,” Albertin said, such as how they acquired the largest brain among the invertebrates, their sophisticated behaviors and agility, and their incredible skill at instantaneous camouflage.

“While cephalopods have many complex and elaborate features, they are thought to have evolved independently of the vertebrates. By comparing their genomes we can ask, ‘Are cephalopods and vertebrates built the same way or are they built differently?'” Albertin says.

Albertin also identified more than 100 genes in the protocadherin family – typically not found in abundance in invertebrates – in the giant squid genome.

“Protocadherins are thought to be important in wiring up a complicated brain correctly,” she says. “They were thought they were a vertebrate innovation, so we were really surprised when we found more than 100 of them in the octopus genome (in 2015). That seemed like a smoking gun to how you make a complicated brain. And we have found a similar expansion of protocadherins in the giant squid, as well.”

Lastly, she analyzed a gene family that (so far) is unique to cephalopods, called reflectins. “Reflectins encode a protein that is involved in making iridescence. Color is an important part of camouflage, so we are trying to understand what this gene family is doing and how it works,” Albertin says.

“Having this giant squid genome is an important node in helping us understand what makes a cephalopod a cephalopod. And it also can help us understand how new and novel genes arise in evolution and development.”

Reference: “A draft genome sequence of the elusive giant squid, Architeuthis dux” by Rute R da Fonseca, Alvarina Couto, Andre M Machado, Brona Brejova, Carolin B Albertin, Filipe Silva, Paul Gardner, Tobias Baril, Alex Hayward, Alexandre Campos, Ângela M Ribeiro, Inigo Barrio-Hernandez, Henk-Jan Hoving, Ricardo Tafur-Jimenez, Chong Chu, Barbara Frazão, Bent Petersen, Fernando Peñaloza, Francesco Musacchia, Graham C Alexander, Jr, Hugo Osório, Inger Winkelmann, Oleg Simakov, Simon Rasmussen, M Ziaur Rahman, Davide Pisani, Jakob Vinther, Erich Jarvis, Guojie Zhang, Jan M Strugnell, L Filipe C Castro, Olivier Fedrigo, Mateus Patricio, Qiye Li, Sara Rocha, Agostinho Antunes, Yufeng Wu, Bin Ma, Remo Sanges, Tomas Vinar, Blagoy Blagoev, Thomas Sicheritz-Ponten, Rasmus Nielsen and M Thomas P Gilbert, 16 January 2020, GigaScience.

DOI: 10.1093/gigascience/giz152

DOI: 10.1093/gigascience/giz152

Study Reveals That Giant Squid Throughout the World Are Genetically Similar

Study reveals that giant squid such as this one are genetically similar throughout the world. David Paul/Museum Victoria

In a newly published study, researchers examine the mitochondrial genome diversity of 43 giant squid samples collected from across the range of the species, finding that there is only one global species of giant squid, Architeuthis.

The giant squid is one of the most enigmatic animals on the planet. It is extremely rarely seen, except as the remains of animals that have been washed ashore, and placed in the formalin or ethanol collections of museums. But now, researchers at the University of Copenhagen leading an international team, have discovered that no matter where in the world they are found, the fabled animals are so closely related at the genetic level that they represent a single, global population, and thus despite previous statements to the contrary, a single species worldwide. Thus the circle, that was first opened in 1857 by the famous Danish naturalist Japetus Steenstrup as he first described the animal, can be closed. It was Steenstrup that realized this beast was the same animal that in the past gave rise to centuries of sailors tails, and even in more recent became immortalized by writers such as Jules Verne and Herman Melville, by demonstrating that the monster was based in reality, and gave it the latin name Architeuthis dux.

It was less than 1 year ago, that the giant squid, Architeuthis dux, was first filmed alive in its natural element. Taken at a depth of 630m and after 100 missions and 400 hours of filming, the footage was captured by a small submarine lying off the Japanese island of Chichi Jima – near to the famous Iwo Jima that was the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting between Japan and the USA in the Second World War.

Now, PhD student Inger Winkelmann and her supervisor Professor Tom Gilbert, from the Basic Research Center in GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen University, have managed to place new bricks into the puzzle of this giant 10 armed invertebrate, that is credibly believed to grow up to 13 meters long and way over 900 kg.

And the two scientists conclusions are: No matter what a sample looks like, its one species all over the deep oceans of the planet.

Sinking to the depths

PhD student Inger Winkelmann says about these findings, that are published in the esteemed British journal, the Proceedings of the Royal Society B:

– We have analysed DNA from the remains of 43 giant squid collected from all over the world. The results show, that the animal is genetically nearly identical all over the planet, and shows no evidence of living in geographically structured populations. We suggest that one possible explanation for this is that although evidence suggests the adults remain in relatively restricted geographic regions, the young that live on the ocean’s surfaces must drift in the currents globally. Once they reach a large enough size to survive the depths, we believe they dive to the nearest suitable deep waters, and there the cycle begins again. Nevertheless, we still lack a huge amount of knowledge about these creatures. How big a range to they really inhabit as adults? Have they in the past been threatened by things such as climate change, and the populations of their natural enemies, such as the planet’s largest toothed whale, the sperm whale that can grow up to 20 m in length and 50 tons? And at an even more basic level…how old do they even get and how quickly do they grow?

The kraken and the seamonk

These new results about the mysterious giant squid are released, fittingly enough, on the 200th anniversary of the Danish naturalist and polymath, Japetus Steenstrup (born in 1813).

At the age of 44, in 1857, it was Steenstrup who saw that many of the monsters of sea-legend were related to fragments that he had been sent of what appeared to be a giant squid, and in doing so described the species for the first time and removed any hope that sea monsters such as the Kraken and sea-monk really existed (although nevertheless, similar monsters still inspired beasts in literature and even films throughout the 20th century, including Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings in 1957).

Professor Tom Gilbert, who lead the team that undertook the research, says:

– It has been tremendous to apply the latest techniques in genetic and computational analyses, to follow up on Steenstrup’s scientific research 146 years after he started it. But its also been a fantastic experience to work with the giant squid as a species, because of its legendary status as a seamonster. But despite our findings, I have no doubt that these myths and legends will continue get today’s children to open their eyes up – so they will be just as big as the real giant squid is equipped with to navigate the depths.

The work was undertaken in collaboration with researchers around the world, including scientists in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Spain, Portugal, USA and Ireland.

Publication: Inger Winkelmann, et al., “Mitochondrial genome diversity and population structure of the giant squid Architeuthis: genetics sheds new light on one of the most enigmatic marine species,” Proc. R. Soc. B 22 May 2013 vol. 280 no. 1759; doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0273

Image: David Paul/Museum Victoria