Baloch women, at the forefront of protests to ensure illegal arrests and detentions do not take place, are alone in pressing for their rights.

Baloch women face off with police in Karachi. Photo: Veengas

Veengas

Karachi: “What you can do? You can only abduct Baloch people. If you want to pick us up, do it,” Amna Baloch tells a police officer.

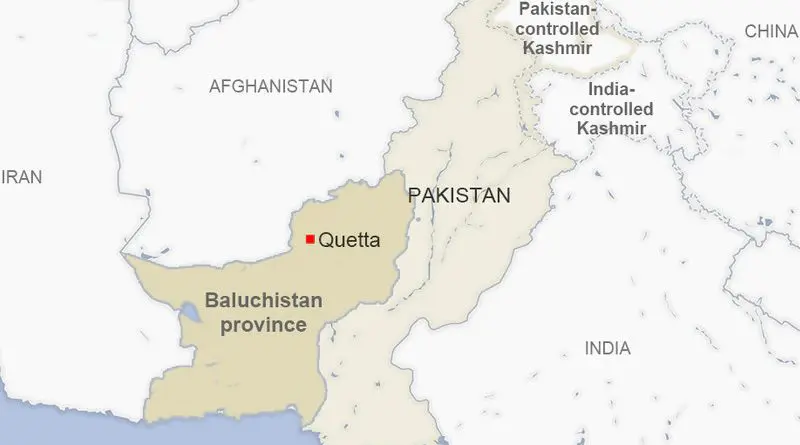

On May 24, the Baloch Yakjehti Committee and Voice for Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP) were to jointly lead a protest rally from the Karachi Press Club to the Sindh chief minister’s house. However, the Sindh government imposed Section 144 and banned political gatherings and rallies. When a few of them gathered to ask about abducted women, they were taken to the police station.

Baloch people have been agitating for the release of all missing persons and in recent times, several Baloch women have allegedly been abducted under the pretext of curbing terrorism.

Mohammad Ali Talpur, a well-known columnist who has spoken for Baloch rights, says that since 1973, Pakistan has been leading a concerted attempt to suppress Baloch people and their demands for rights.

“The policy of abduction, killing, and dumping reared its ugly head in 2000 and then in 2008, it rapidly increased. In 2008-2009, the Pakistan People’s Party government spent Rs four million [Pakistani rupees] on counter-insurgency, in addition to paying amounts to death squads in Balochistan,” Talpur says.

So brazen are the attacks on Baloch people, that police do not even back down from launching assaults in front of media.

“Do not touch him,” Sammi Deen Baloch, a human rights activist, and deputy general secretary for VBMP, cried loudly as police officers and men in civilian clothes attempted to pick up a Baloch man at the Karachi Press Club.

Under pressure, police ended up releasing the Baloch man. Officers told media that the action was against the flouting of Section 144.

Meanwhile, Amna Baloch had a different version. She said that there were only four of them, and they did not chant a single slogan but just asked about two Baloch women who had earlier been taken to the police station.

Also read: ‘Tell Us Whether We Are Orphans’: In Pakistan, No Respite for Families of Baloch Missing Persons

Wracked with worry about the two women, Amna says that police initially were unwilling to share details. When Amna, Sammi, and other Baloch protesters pressed them, they said the two were in police custody.

When this reporter took a photograph of police gathered at the scene, she was asked to delete the photo. Eventually, explanations on her nature of work seemed to suffice. However, to questions on where the two Baloch women were kept in custody, police remained mum and instead, laughed.

This reporter also overheard police discussing the eventual picking up of Sammi, one of the four asking after the two Baloch women.

“Look at her (Sammi), she speaks a lot, you should abduct her,” one man in civilian clothes was heard telling police.

By then, reporters had surrounded Sammi. Some of the reporters asked police how she had violated Section 144, and what pretext police could have of taking her to the police station. To this, officers had no answers.

The women were eventually taken to the police station and released afterwards.

Sammi and others being taken to the police station. Photo: Veengas

After a few hours, videos of this went viral on social media. The Sindh government, later, took notice of the incident.

Nida Kirmani, an activist, was taken along with the Baloch women to the police station. But Nida, a non-Baloch woman, was apologised to by police. Baloch women were asked to take off their masks and niqab. Nida shared her experience on Twitter.

Political activist Mahrang Baloch said that abducting Baloch women has been publicly justified by law enforcement ever since Shari Baloch attacked Karachi University.

After the University incident, Baloch students in various institutions were harassed in the guise of investigations, including in Punjab universities.

“But Baloch women had been targets long before. In Awaran, a city of Balochistan, security agencies had abducted Baloch women in an explosives case. Later, allegations proved untrue. Those women were so poor they had no slippers on their feet. Pakistan security forces target common Baloch citizens, even those who aren’t rights activists,” Mahrang said.

Mass graves were found in the province, she added.

At the KPC protest, Amna said that the state’s violence was a cause of constant fear and sorrow. Sammi, for instance, has been agitating for the release of her father.

Mahrang’s father, Abdul Ghaffar, was abducted in 2009 and his mutilated dead body was recovered from Gadani on July 1, 2011. In 2017, her brother was abducted but released after four months. She has received threats to end her political activism.

Even Balochistan home minister Mir Zia Lango once taunted her, noting that the state had not apprehended her yet.

“When my number comes, they will definitely abduct me,” Mahrang said. “If the agencies can arrest Noor Jan, who lives in the much more central Hoshaap area, then who am I?”

Mahrang along with VBMP leaders, led a sit-in in front of the Balochistan chief minister’s house demanding knowledge of missing persons and Noor Jan, a 40-year-old Baloch mother of three, who was abducted in a suicide bomb case. The FIR says she was apprehended wearing a suicide jacket. Initially given a death sentence, she was released on bail.

Baloch women and men in a sit-in in front of the CM’s house in Balochistan.

“How is possible that a mother will wear a suicide jacket at 3 am in the house where her children are sleeping?” asks Mahrang.

One Habiba Baloch was dragged by male security officers from her home in Karachi and released after four days.

Mahrang also cites the example of Hafeez Baloch, who is an MPhil student at Quaid-e-Azam University of Islamabad, who was picked up and charged allegedly in a fake case.

Mahrang is also worried about conservative society in Pakistan that is ready to point fingers at women who are outside at night. “When Baloch women are made to spend days in the custody of security agencies, you know what and how society thinks,” she said.

Many see in present day Pakistan’s treatment of Baloch women a reflection of how Bengali women were treated in East Pakistan.

Silence of human rights groups

Human rights groups and political parties remain silent on the mistreatment of Baloch women.

Recently, Shireen Mazari, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf leader and former minister for human rights, was arrested by the police. In Pakistan, people condemned it and Islamabad high court sat at night to rule in the case. The same reaction is absent when it comes to Baloch women.

Talpur says there is a clear difference of perception.

Sammi criticised the role of feminists in Pakistan who raise voices in selective cases but when the question comes to Baloch women, they are silent. “Why does their feminism end at Baloch women?” Sammi asks.

Also read: Pakistan: Family of Baloch Activist Who Died in Canada Claim Harassment by Authorities

Mahrang added that if the Balochistan government and other political parties genuinely wanted the removal of the FIR against Noor Jan, they could have asked for it.

She criticised political parties who, when they are in opposition, speak about Balochistan for their vote banks, but when they come in power, they speak for Kashmir first and then for Islam. “Balochistan was and is never their priority. For instance, the sitting government’s interior minister Rana Sanaullah rejected a commission for Baloch students who have been made to disappear. He belongs to Pakistan Muslim League, led by the same Maryam Sharif who once promised us that she would look into our matter,” Mahrang said.

On the other hand, human rights organisations follow the state’s narrative in the case of Balochistan. “We (Baloch women) force them to issue statements. Otherwise, they do not care about us,” she said.

Baloch women entered the protest arena asking for the release of their fathers and brothers. Mahrang said that the time will soon come when Baloch fathers and brothers will need to agitate for the release of their daughters and sisters.