The government is putting stricter restrictions on vaping than on smoking. That’s bad for public health.

Clive Bates

Writes The Counterfactual by Clive Bates ·

Aug 8,2022

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

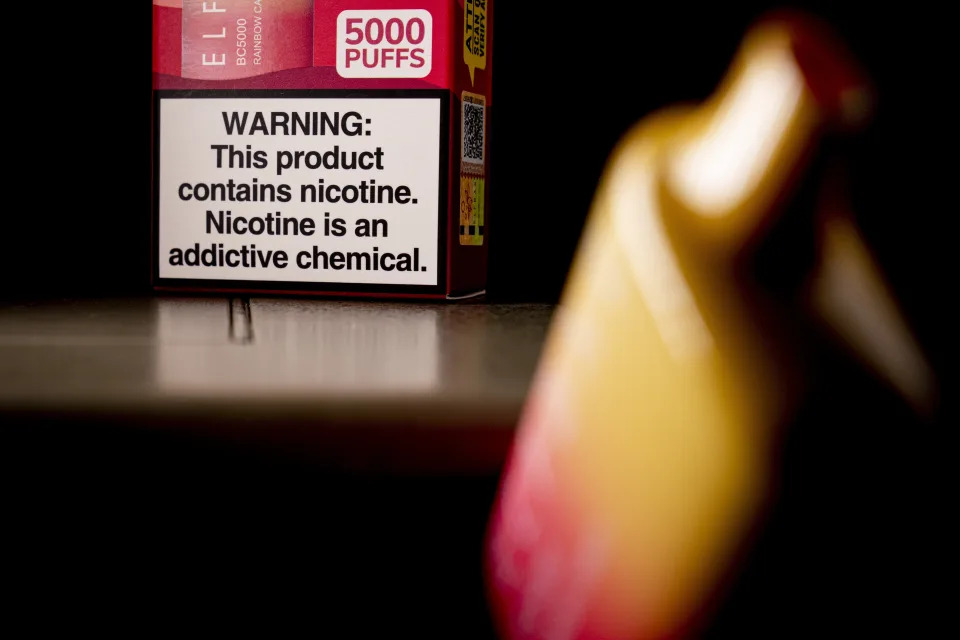

While the boiling controversy over the use of e-cigarettes—popularly known as vaping—can seem like a quirky but noisy sideshow, in reality, millions of lives are at stake. E-cigarettes were first commercialized around 2006 and work by heating a nicotine liquid to create an inhalable mist, rather than by burning tobacco to create smoke. Though not completely safe, vaping is far less dangerous than smoking combustible cigarettes, the dominant product for nicotine use.

Despite this, the Food and Drug Administration has been cracking down on vaping—often claiming that vaping poses a health risk and is a threat to young people. This overly cautious approach is hindering a technology that will help eliminate the burden of disease, death, and suffering caused by smoking.

People smoke primarily to experience the effects of nicotine—for stimulation and pleasure; to reduce stress and anxiety; and to improve concentration, reaction time, and cognitive performance. For some people, these effects improve their quality of life. But on the dark side, nicotine use can lead to dependence.

Crucially, however, it is smoke, not nicotine, that causes the overwhelming burden of disease and death. Inhaling the toxic particles and gases from the burning tip of a cigarette exposes the body to thousands of chemicals, of which hundreds are known to be hazardous. The result is widespread death and disease, with cigarettes killing 480,000 Americans annually and leaving around 16 million suffering from a smoking-induced disease. Without the harmful effects of smoking, nicotine use starts to look more like moderate alcohol consumption—a modest substance use that fits within the normal risk appetites of modern society.

With vaping, we have a solution to two related problems. First, millions of American smokers have the option of switching from smoking to vaping, greatly improving their health prospects. Second, people in the future who want to use nicotine will be able to do so with considerably reduced consequences.

In a liberal society, we should not prohibit or aim to eliminate drug use or pretend that it can be risk-free, but we should try to limit the risks to the extent possible. Vaping is the best opportunity we have to do that for nicotine.

Critics of vaping typically rely on three main arguments.

First, we do not know the long-term consequences of e-cigarette use. This is true, as it is for any new product. We will have to wait another 50 years to know the full story. But what we do know today is that cigarettes are very dangerous. Additionally, all the available evidence suggests that vaping is much less harmful than smoking.

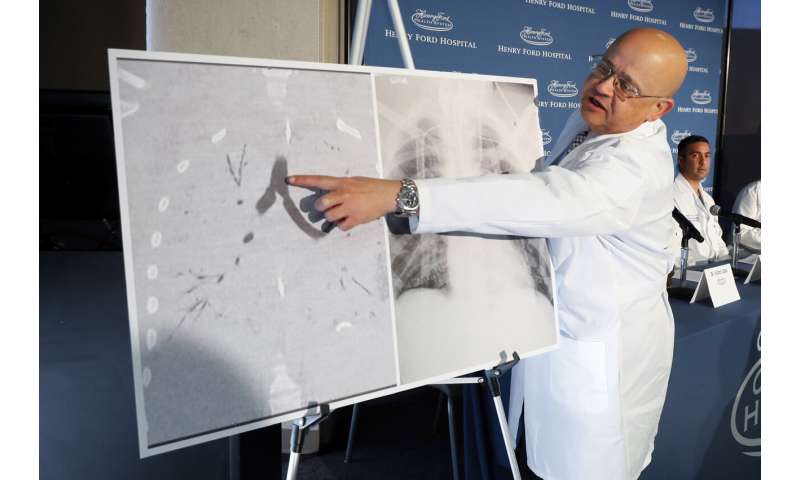

Second, vaping skeptics point to the outbreak of lung injuries in 2019 in the United States—which caused 2,800 hospitalizations and 68 deaths—as evidence that vaping is potentially extremely dangerous. But while this outbreak was initially attributed to e-cigarettes, it turned out to be caused by illegal and unregulated cannabis vaping products that included a dangerous cutting agent, Vitamin E Acetate, which is not added to nicotine liquids.

Third, opponents will claim that there is a “youth vaping epidemic,” pointing out that high school-age vaping reached 27.5% in 2019. While there has been a considerable uptick in youth e-cigarette use in recent years as the technology developed, the high 2019 numbers are an outlier. The headline number of the study measured any vaping in the past 30 days, and around two-thirds of users said they were making infrequent use of these products. Additionally, those vaping frequently were likely to have smoked previously, and it is possible that their vaping was a diversion from lifelong smoking. Furthermore, by 2021, the number of high-schoolers who had used a vape in the last 30 days had fallen to 11.3%, suggesting that claims of an “epidemic” were likely premature.

Together, these concerns have gained so much purchase among the general public that most Americans wrongly believe that vaping is just as harmful or more harmful than smoking. Even worse, the visceral politics around vaping, in particular the idea of the youth vaping epidemic, have driven the F.D.A. to apply overly burdensome and restrictive regulations on vaping products.

As a result, over one million vaping products have been denied access to the U.S. market, and the great diversity of flavors and device types have been cut down to a handful of uninspiring tobacco-flavored products. In stark contrast, no public health test applies to the 3,000 cigarette products that have been on the market for years throughout America. They were grandfathered in under the 2009 Tobacco Control Act.

In June, the F.D.A. announced that it had denied marketing applications made by Juul Lab Inc., one of the world’s biggest vaping companies with around three million adult users of its products. The F.D.A.’s case against Juul was very weak—it did not rely on youth vaping or any identified risk to health with the product but on some “inconsistent and conflicting data” in Juul’s 125,000-page application. These should have been addressed through discussions between the applicant and the regulator, but Juul argued in court that the F.D.A.’s “scientific” reasons were a feeble pretext for a politically-motivated attack. The F.D.A. withdrew from the legal proceedings and will review its approach internally.

Despite this recent victory for Juul, the F.D.A.’s interventions have resulted in an anarchic market of a few authorized vaping products, thousands of products either under review or pending legal challenge, and an emerging black market for unregulated vape products.

If the F.D.A. is taking a tough stance on safer alternatives, what is it doing about cigarettes, the product that causes the most harm? In 2023, it plans to publish a plan to reduce nicotine levels in cigarettes to very low levels. The F.D.A. argues that this would make the products minimally addictive, help smokers quit, and prevent youth uptake.

The problem with this approach is that it amounts, in practice, to a prohibition of cigarettes in their traditional form. But most smokers won’t just quit as the F.D.A. hopes. Some will buy cigarettes on a black market while others will hand-roll their own or switch to cigars. And though it would be good if some smokers responded by switching from smoking to vaping, the F.D.A. seems to be working hard to make that option more difficult.

Ultimately, the most likely fate of this poorly constructed proposal is that it will be debated until it is no longer needed. Many consumers who wish to use nicotine will switch to products such as e-cigarettes that cause them much less harm but still allow them to experience mild psychoactive effects of nicotine.

This transition is already underway and likely to continue because it is highly beneficial to those directly involved, both consumers and suppliers. The question is the extent to which misguided, highly risk-averse regulators and prohibitionist activists slow the pace of change. Every day of delay will mean more avoidable death and disease.

Clive Bates is Director of Counterfactual Consulting a public and sustainability practice. He is a former civil servant and former Director of Action on Smoking and Health (UK), a leading anti-smoking non-profit.

[The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to the industries discussed in this article. He has filed an amici curiae brief in support of Juul’s motion for a stay pending substantive review on public health grounds after the FDA denied Juul’s applications to market its products in the United States.]