The Human and Ecological Price of Renewable Energy on Tamil Nadu's Coast

Madhu Ramnath

21/Jan/2026

THE WIRE

Fisherfolk and coastal residents speak of lost livelihoods, eroding shores and ignored voices as offshore wind and other projects advance along the coastline, against scientific warnings.

Fishermen in Thoothukodi say flyash dumped from thermal plants have reduced their catch.

You see the sea from outside, as an object to be viewed for entertainment, to pass your time, or to relieve you of stress. For us it is a God who feeds us. If we lose our focus even for a day, we will perish. We are a people who catch fish worth ten rupees and make a living. Each day the sea air mixes with our blood, and nobody understands this. They just see the sea as something big, with nothing happening in it, which is why so many development projects are brought to the coast.

(A member of the Periyathazhai community.)

India’s renewable energy goals

India is making great strides to achieve its promised goals in the move from fossil fuels to renewable energy, made at the Conference of Parties (COP21) held in Paris. In November 2022, the Union Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and the Danish Energy Agency (DEA) made a conceptual plan involving 15 locations for offshore wind in the country, 14 of which are to be in Tamil Nadu and one in Gujarat.

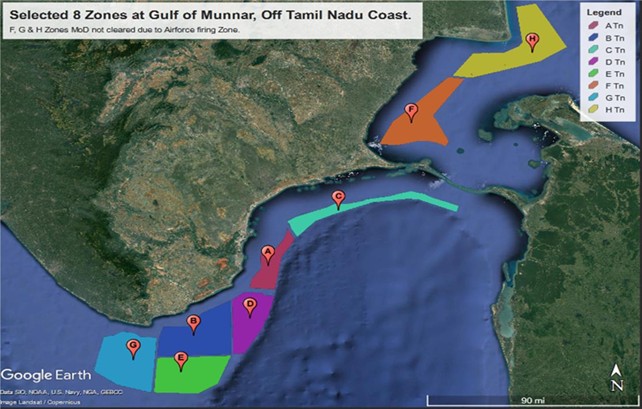

These offshore wind farms are meant to occupy hundreds of acres in the sea, stretching from Kanyakumari to the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Bay regions, along the districts of Kanyakumari, Thoothukudi and Ramanathapuram. Studies for these farms have been conducted by the Centre for Excellence for Offshore Wind and Renewable Energy, a joint initiative of the DEA and the MNRE.

India’s goal to install 500 gigawatts (GW) of non-fossil fuel energy by 2030 is progressing well. The target for the Tamil Nadu project is 30 GW. As of end March 2024, the country’s renewable energy power capacity is about 43% of its total installed capacity, which is 190.57 GW. The cumulative installed capacity is now 441.97 GW, up from 275.90 GW in 2014-15.

According to the MNRE, solar energy overtook wind energy in India – its share rose from 9.97% to 81.81% between 2015 and 2024. Within solar energy, ground-mounted solar is the most prominent category. In October 2015, an Offshore Wind Energy Policy was published by the MNRE, followed by a strategy paper in 2022, titled ‘The Establishment of Wind Energy Projects’, which outlined three models for development, each depending on the studies and surveys conducted (or to be conducted), the sites and areas of operation and whether financial assistance would be available from the government.

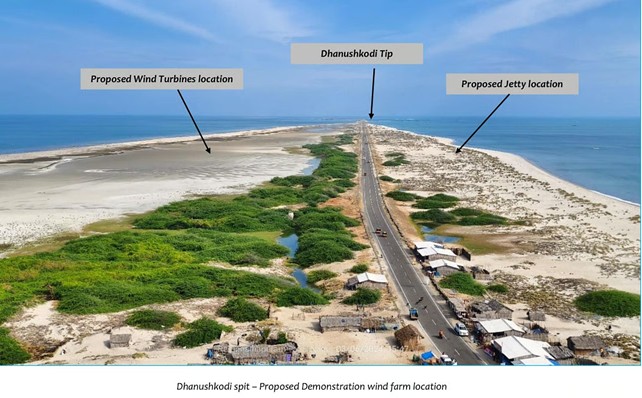

The National Institute for Wind Energy (NIWE) has identified a test facility for testing wind turbines in Dhanushkodi, the southern tip of Pamban island, in Ramanathapuram district. The facility is spread over 75 acres, with intended installation of four turbines to generate 50 megawatts (MW), for studies and data, at a cost of Rs 350 crore. About 70% of the cost is towards the pile foundation. The mast in offshore wind installations is at least 100 metres, with 50 metres of it below the seabed.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for this project states that excavation for the foundations will remove plankton and benthic animals, and the resulting turbidity could affect shellfish and clog the gills of several species of fish. The turbine testing facility was subjected to a rapid marine EIA, conceptualised by the NIWE and the MNRE, and conducted by Indomer Coastal Hydraulics (Pvt) Ltd., a Chennai-based company, given that role under the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) of the United Kingdom. (More detail about ASPIRE is available at the FCDO.)

Source: Project Environmental Impact Assessment. The site is a wetland and falls in different Coastal Regulation Zone areas.

The human angle

Despite numerous pre-feasibility and feasibility studies conducted by various agencies, the human element was missing, or mentioned only in passing. The opinions of the coastal people and fishers, in whose waters these projects are planned, were often absent – as they were often not informed or consulted about the projects.

All along the Tamil Nadu coast, a number of projects have been implemented, and more are planned. These include a heavy water plant, a nuclear plant, zirconium mining, deep sea mining, seabed sand mining, thermal plants, a rocket launch pad, captive ports, harbours and jetties – and the newly proposed offshore wind farms.

Map showing proposed and existing projects along the Tamil Nadu coast. Source: Coastal Peoples Federation, Nagercoil.

Interspersed below, alongside the descriptions of the most recent of these projects – the Offshore Wind initiative with the pilot turbines in Dhanushkodi – are the testimonies of locals, the people who will be the most affected by such a project, but whose views have found no space in the public domain. Most of the people spoken to for this report belong to the fishing communities and requested anonymity. Wherever possible, the names of the villages are mentioned.

Map showing the area of interest for the offshore wind energy project.

Voices from Periyathazhai

Periyathazhai literally means “big thazhai”, referring to a large Pandanus odoratus tree, a common coastal species that is threatened by indiscrimate clearing. Here are the views of two locals about the project proposals:

Since the Kudankulam nuclear power plant protests, almost no project has been preceded by public hearings. They want to end coal, find something to replace coal. They go to solar energy, wind energy, more energy…. But [they do so] without talking about reducing or balancing our energy needs or distributing energy equally, and only wanting to produce more and more energy. Coal has destroyed the land, and now we want to create energy in the sea, forgetting that this will impact the people who depend on the sea negatively. The southern districts of Tamil Nadu, from Rameshwaram to Kanyakumari, span 500 kilometres – about half the Tamil coastline, and are home to the most densely populated fishing-community belt in the state. And here we have a developmental project every 5 kilometres. Why is this happening? For whom? It is to satisfy the insatiable hunger of the corporate sector of the world, for which the sea and the forsaken people are being wiped out?

The sea is not just the water. It includes the sand, the land at the edge, the living beings in it. Take the turtle. It needs land to nest, and it returns to the same spot to lay eggs every year. What a wonder of nature! But with tourism, the same land won’t be there, as it is destroyed or changed. People don’t even believe that sand has life, that life originated in the sea is now being studied – which means that the sea and the coast are alive.

Voices from Manapadu: ‘This project will hurt us’

They [the government] say that the earth is heating up, so we need to do this [find other sources of energy than coal]. They say that it won’t be like coal – there won’t be fly ash. What they will say if we oppose this is that it is necessary for development. Fine, but we will accept it if there are no bad impacts. This project will be very negative for us, and for fishing, as it will be within 3-4 nautical miles [of the coast]. Something happening in Chengalpet will affect the sea up to Chennai. For instance, the anchors lost by small boats even years ago still damage our nets. This project will completely destroy our livelihood. If there are cables running for a kilometre from the shore into the sea, they will restrict fishing; it will become a private area. The very conditions it will create will hamper us. Any scheme within the sea will affect fishing. There is no scheme that can happen in the sea that won’t negatively impact fishing and fishermen.

The Manapadu estuary, one of eight prime locations for port investments under Tamil Nadu’s ‘Blue Economy’ initiative. The primary purpose is to develop infrastructure for coal and LNG jetties, to support coal-based thermal plants. The local fishing communities have opposed the project. Photo: Madhu Ramnath

If they introduce a scheme that impacts 20% of fishermen, can they create a project that takes care of these 20%? They don’t even have such an intention. Can the government show that because a certain project in an area, the people of that area are doing better? Such an example – of a people satisfied with a project – who say that a hundred people were educated in their village and they got jobs, and that their village was now doing well – that cannot be said about any scheme of theirs. The government can point to any four villages where they have implemented some scheme and ask two of the villages to speak about the benefits they have received…that they were satisfied, that they had better water, etc., but there is nothing like that. [They only say] that they have been impacted negatively, that promises were not kept. There is nothing like employment for us. Even here, only the people who come from the north are given employment.

Many of our nets get damaged in the jetty. They [the government] had said that if we lose Rs 10,000, we will get that back, even Rs 1 lakh will be compensated. But nobody even comes to see the damage, let alone pay for it. Actually, we have to see the damage, make a complaint and take it to the officer concerned, which is then processed… As far as I know, only one complaint has made it the whole way, but even that has not been paid [compensated]. They said there were no funds for it – even for such a large project, no fund was kept aside for this. They never seem to do anything right.

From Idinthakarai

Idinthakarai is a coastal village about 25 kilometres from Kanyakumari, the site of protests against the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant in Tirunelveli district. “Idindhakarai” means broken shore, a reference to the damaged coastline of the region. Here is what several locals said:

The government tells us that projects will bring more jobs. But does one livelihood have to be wiped out for another?

There used to be an abundance of lobsters on our coast, now that has declined. Nor is there much seaweed. The ribbon fish, also known as cavalai meen [Lepturacanthus savala], is hardly found now.

There is much erosion of the seashore; the groynes meant to prevent damage create new sand formations, which cause conflicts among fishermen who need that space to land their boats.

According to a shoreline assessment report by the National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR), a branch of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Tamil Nadu lost 1,802 hectares to sea waves at 22 locations identified as ‘erosion hotspots’. Several southern and delta districts are mentioned in this report, including Thoothukodi and Ramanathapuram. The latter has lost 413 hectares of shoreline, the most in the state. As one fisherman said:

My personal understanding of agitations came with the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant. Leaders don’t emerge nowadays, and there is no popular support for a cause. Opposition parties support an agitation until the elections are over, and then they leave.

In Periyathazhai, I asked whether anyone was making the local communities aware of the issues. The state government? The Union government? What are these development projects? Why were they here? Was there any discussion? And the responses this author got echoed the three persons cited below:

Nothing of the sort. They are afraid to meet people. The Kudankulam protest took place for many years and, after that, they (the government) work only through dadas (goons). In fact, any project, before commencing, requires a public hearing. But for the last 5-6 years, there have been no such hearings. Earlier, any proposed scheme was discussed at the collectorate and the concerned departments would come together and talk about it. They would then meet the people and explain the matter to them. We have an ISRO [Indian Space Research Organisation] project here. For this, there were no public hearings. They announced it sometime earlier, but work began about a year ago. This project was always on the cards, but the last public hearing was held for Kudankulam. We had opposed that too, but they did not listen to us.

On the way here, you must have seen a thermal plant when you crossed Kallamuli, the Udangudi Thermal Plant. But it is not in Udangudi; it’s not even in the Udangudi Panchayat. That [other] project in Kulasekarapatnam is not in Kulasekaram at all, but in Madhavankuruchi Panchayat. None of these projects have asked for people’s opinion or consent.

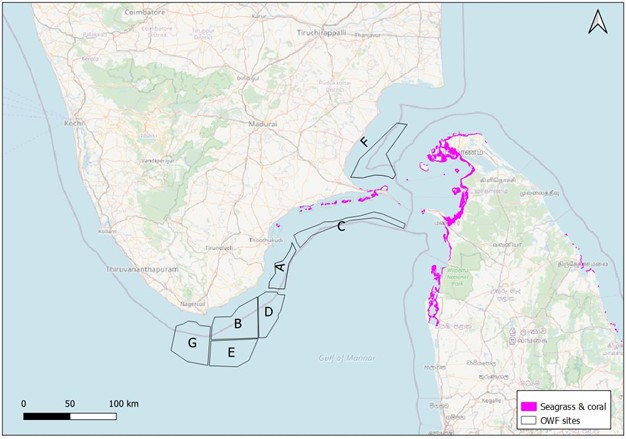

Seagrass and coral sites. Dugongs feed almost exclusively on seagrass, forming a symbiotic relationship. Source: Centre of Excellence for Offshore Wind and Renewable Energy, 2022. Source: Maritime Spatial Planning for offshore wind farms in Tamil Nadu.

See the sand on the shore. There are thousands of life forms in it. But it is being destroyed due to tourists and tourism, and the filth they leave behind. Go to Marina beach, get some sand. Then go to a village near Dhanushkodi and get some sand. One will be dead sand, one will have some life in it. They have begun to destroy Dhanushkodi, also in the name of spiritual tourism. The sand at the shore is food for the mosses, for the turtles. Not only that, where the sea and sand meet there is oxygen. There are many elements in these sands, and it is only when these sands mix with the water that the sea water gets its required density.

Reactions in Nagercoil

The existing windmills are more than sufficient for the energy we need. If we need more, why not use some lands in Ramnad for solar farms? The economics of OWE is incorrect – more input than output. You need to count the impacts as input. Windmills are being planned in the fishing grounds of the people and that will impact their livelihood.

Government records show that temperatures are rising and the shore is eroding, leading to a decline in fish. In Kanyakumari, the sea has advanced 26-27 metres over the last decade. OWE will change ocean currents and wind directions, which will affect the small boats of the fishermen, especially their ability to steer. There will be problems during the drilling – noise and earth shaking – which will affect the migration of fish. Pollution will affect the food chain and biodiversity. There will be problems when the equipment wears out and needs repair or replacement.

Marine ecology of proposed project area

Twenty-seven species in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region are vulnerable and eight are critically endangered. The government’s website on Ramsar reports that, “4 of the 7 sea turtle

species found worldwide are reported here – Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), Green Turtle

(Chelonia mydas), Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and the Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). All 4 species are protected under Schedule-I of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act (1972), and also listed in Appendix-I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)”.

It is quite obvious that the locations for the offshore wind energy projects lie close to, or within, the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay regions, which host a multitude of vulnerable, endangered and threatened marine and other species. In addition, the coastal length used for fisheries in Tamil Nadu runs parallel to the project sites.

The gulf region consists of estuaries, mudflats, beaches and forests in the near-shore environment and includes algal communities, seagrasses, coral reefs, salt marshes and mangroves. There are 21 islands in the area, where fishermen land during their expeditions, using these islands as their landing spaces.

The Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve hosts 3,600 species, including the globally endangered dugong, and six species of mangrove endemic to India. There are 117 species of corals (live coral was observed within a 10-kilometre radius of the project area, and dead coral within a 12-kilometre radius), ten divided into 14 families and 40 genera (of the 89 found in India).

Note that under the Indian Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, all coral species are protected. There are about 100 species of echinoderms – Sea stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, etc. – in the Gulf of Mannar that live among the corals and have been observed about 5 kilometres from the project area. Also, 321 species of sponges of 129 genera have been recorded. Of these, 63 genera (and 257 species) are endemic to the area. In addition, 67% of the sponges in India are found in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay regions.

The dugong is a flagship species in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region, with a symbiotic relationship with seagrass, and highly endangered worldwide. It is now recognised that both dugongs and seagrasses are endangered due to several factors, chiefly habitat destruction and climate change.

As recently as June 2025, the Tamil Nadu government issued an order declaring the 524.78 hectares of Ramanathapuram district as part of the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve. It recognised that the area is extremely important for both resident and migratory birds and serves as a key stopover along the Central Asian Flyway with essential feeding and resting grounds. Some 128 species of both migratory and resident birds have been recorded in the area, and in the 2023-24 census, 10,761 birds were recorded there. The Dhanuskodi village and its surroundings in the Ramanathapuram district is to be declared a Greater Flamingo Sanctuary for the conservation of this ecology, particularly bird species.

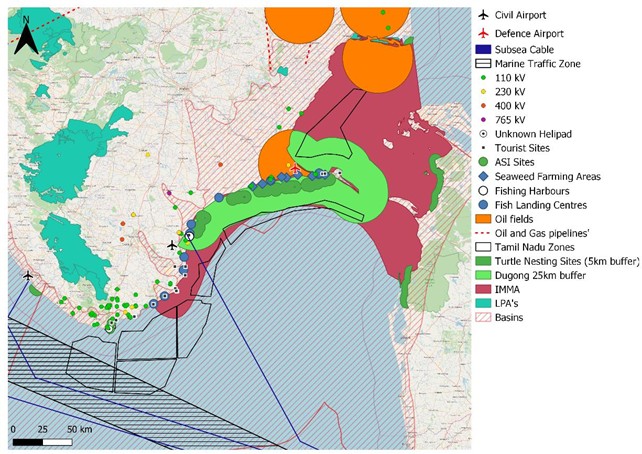

Map showing ecological sensitive zones and fishing related sites along the proposed project areas.

Source: Centre of Excellence for Offshore Wind and Renewable Energy, 2022. Maritime Spatial Planning for offshore wind farms in Tamil Nadu.

Tamil Nadu has five bird sanctuaries, two national parks, one wildlife sanctuary and one biosphere reserve. In addition, it has ecologically important coastal areas, such as the Pulicat Lake (with lagoons), the Gulf of Mannar (sensitive for coral reefs) and Pichavaram, Vedaranyam and Muthupet (sensitive for mangroves).

An EIA was conducted as per norms approved by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC), after ‘discussions’ with NIWE. The report was submitted to the CRZ Board (It is not in the public domain but was available through one of the board members). The Gulf of Mannar Marine National Park (GMMP) has a core area of 560 square-kilometres (from Rameshwaram to Tuticorin) within the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve, an area of about 10,500 square-kilometres on the southeastern coast of India.

It is the first Marine Biosphere Reserve in Southeast Asia, established in 1989 and recognised by UNESCO, it is also a Ramsar site, recorded as No. 2472, and was intended to conserve and protect the dugong and the whale shark, among thousands of other species. It is the world’s richest region in terms of marine biodiversity. Some marine species have a range of 15 kilometres (such as dugongs) but others (like the turtles) may have ranges of many thousands of kilometres. The buffer and core zones of the biosphere reserve would be impacted by the project as well as each stage of its implementation.

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) – the total environmental impacts generated by a system, process or activity over an ecosystem or persons throughout its lifespan – of the materials used in the construction of the turbines is detrimental to the environment. Most of the material used in OWE are harmful to human and environmental health.

These materials include metals, concrete, laminar compounds, fibreglass, plastics, epoxy resins, rubber, oil derivatives (lubricants), rare earth elements and oil (fuel). The metals are essentially Aluminium (Al), Iron (Fe), Zinc (Zn), Copper (Cu), and Steel, all of which demand land and freshwater during their extraction and generate industrial wastewater discharges when the turbine parts are fabricated. A number of conflicts in the world can be traced back to the extraction or control over some of the critical minerals (cobalt, lithium, nickel, molybdenum), which are concentrated in a few countries, as in the DRC and the Sibuyan Islands in the Philippines.

The noise level due to the construction, especially by pile driving, will be very high. Studies say that the levels will be as high as 208 dB, peaking at 244 dB re 1 μ Pa20 at 1 metre; the EIA, however, only mentions a noise level of 120 decibels (dB) at 3 metres (or 129.5 dB at 1 m), which is misleading.

Pile driving will remove the biota at the foot of the wind mast in a marine geological formation consisting of calcareous reef; these negative effects will be repeated in the construction of a jetty.

According to a report by FOWIND, a partnership between the European Union and India on Clean Energy and Climate, several important parameters of the Tamil Nadu offshore wind projects require more scrutiny. These include:Wind resource assessment, which carries high uncertainty.

Metocean climate (water), with limited wave and current data and high uncertainty.

Geotechnical conditions, due to limited seabed geology information.

Grid connection, which also carries uncertainty.

The report also notes that, as yet, “there is no regulation in place stipulating ESIAs for the wind sector in India.” The impacts of offshore wind developments depend on the site and scale of the project, making pre-construction analysis essential. Currently, India has a framework—the 2015 National Offshore Wind Energy Policy—that mandates EIA studies. However, there is no unified national EIA law for offshore wind projects. Work on the ground proceeds based on rapid EIAs and specific guidelines that attempt to ‘balance’ development and environmental protection in sensitive zones.

In its feasibility study report, FOWIND categorised almost all parameters as either ‘medium risk’ or ‘high risk’; none were placed in the ‘low risk’ category. Other considerations include bathymetry, soil conditions, jack-up vessels, ports and logistics, and ESIA. FOWIND has made detailed recommendations to mitigate these risks.

Beyond technical and ecological drawbacks, India’s legal framework emphasises the need to protect marine biodiversity. Yet the human angle remains largely unaddressed, as evident from the testimonies we have read. There has been little attempt at public hearings, or to take people’s views, cultural practices, or livelihood concerns into account when designing the demonstration facility or the larger envisioned project.

Thermal plants like this one, photographed at night, generate tremendous flyash that pollutes the water, air and soil, leading to declines in fishing yield.

Though renewables now constitute about 50% of the installed power capacity, thermal power is still the source of much of the country’s round-the-clock electricity demand. There is little chance that India will be able to deal with its climate commitments before 2047 without compromising its economic ambitions.

The key issue in energy, as renewables expand in the power sector, is energy storage. Other aspects include better distribution, including better metering and improved technology. Before going ahead with the planned installation of offshore wind farms, it is crucial to make existing thermal plants more efficient. Alongside the obvious and important considerations of marine ecology and seascapes, the impacts on human lives and livelihoods need to be taken into account.

Madhu Ramnath is a botanist, anthropologist and writer. He is the author of Woodsmoke and Leafcups.