L-R Fortescue CEO metals Dino Otranto, executive chairman Andrew Forrest and CEO growth and energy Gus Pichot. (Photo by Kristie Batten.)

Fortescue (ASX: FMG) founder and executive chairman Andrew Forrest said on Friday that the company was progressing critical minerals projects despite not understanding the “fuss” surrounding the strategic metals.

Speaking at Fortescue’s annual general meeting in Perth, Forrest said the company remained committed to its critical minerals projects but questioned the hype following a deal signed by US President Donald Trump and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on October 20.

“It was good. Knock yourselves out. I mean, I don’t see anything that rare about critical minerals,” Forrest told reporters following the meeting.

“You’ve got declining strategic commodity prices everywhere. I don’t see the fuss, but anyway, other people do so it’s good for the business. We’ve got plenty of critical minerals, which we’re happy to get out of the ground.”

Despite downplaying the sector, Forrest admitted Fortescue was exploring for rare earths in Brazil, where CEO of growth and energy Gus Pichot had discovered “buckets” of material.

“There’s nothing rare about rare earths. [Pichot’s] got a small ocean of it,” he said. “I’d like to see it developed and cranking across to Louisiana and getting developed.”

His comments coincided with Fortescue’s wholly owned subsidiary Wyloo Metals and joint venture partner Hastings Technology Metals (ASX: HAS) signing a non-binding agreement with Ucore Rare Metals (TSXV: UCU). They will explore a long-term offtake agreement for concentrate from the Yangibana project in Western Australia and hydrometallurgical processing options in Louisiana.

Failure key

Forrest reaffirmed Fortescue’s commitment to achieving real zero emissions by 2030, defending the company’s investment in decarbonization.

“This $6.2 billion investment we took back in 2022 will pay dividends. I give you my assurance and sure, we’re the guys up front with the arrows in the back, to be dragged down and told we failed here, we failed there,” Forrest told the meeting.

“Honestly, it just put steel into the spine of the 20,000 people who work at Fortescue getting constantly criticized. Decarbonization is not a straight line. It demands creativity, experimentation and relentless innovation. We’ve literally had to invent our way through.”

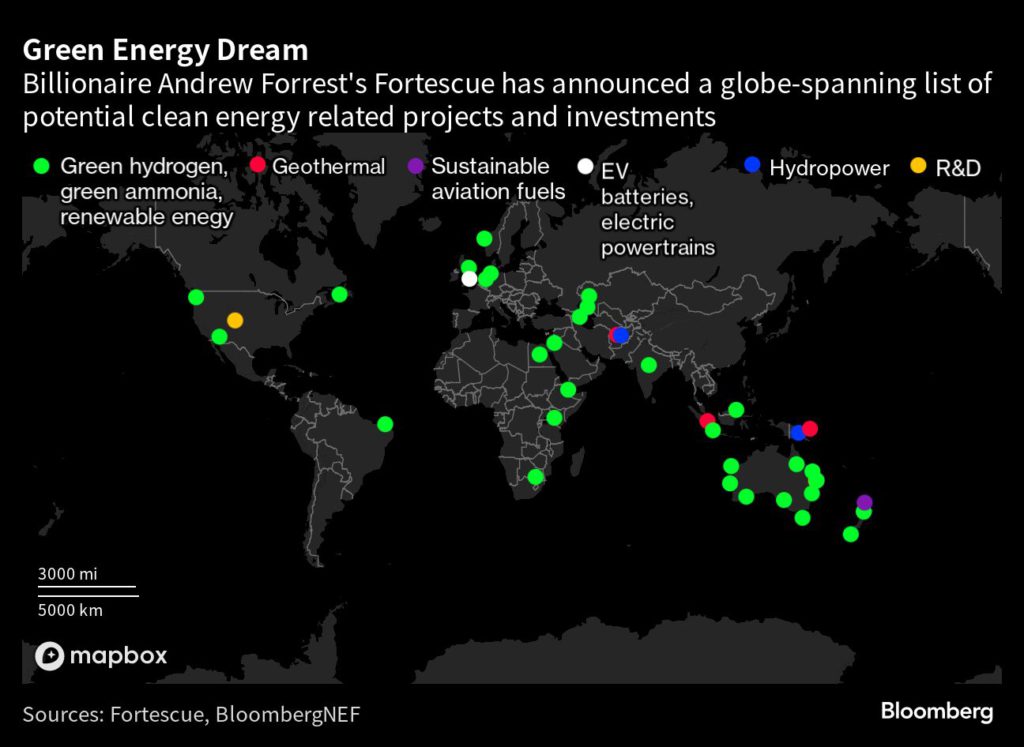

Fortescue has walked away from some of its green hydrogen projects amid weak economics, but Forrest said trying and failing was the “fast track to success.”

“We specialized into hydrogen, believing it would get really big – it hasn’t yet,” Forrest said. “What is enormous is replacing fossil fuel-generated energy with renewables, firmed by the breakthrough we’ve all seen in batteries. That is a crossover point in history, and that’s beginning to happen.”

Forrest conceded there had been job losses in its green energy division but said Fortescue was creating jobs elsewhere.

“I don’t know the net number, but we’re swinging harder and harder into R&D. That is where the value is,” he said.

“We’ve got smartest people in the world working for us. Other people can do spectacular manufacturing. We did what we said we’d do. We’d see if we could compete on manufacturing. We couldn’t, but we can definitely compete on R&D.”

Trump, big oil criticized

Forrest also took aim at big oil companies and Trump, accusing them of dividing the world on climate change.

“You’ve got a President of the United States who declared that climate change is the greatest con job in history, straight in the face of massive investment by some of the smartest people I will ever meet,” he said.

“We’ve got these two stories unfolding, one of progress, one of retraction. One side is racing to deploy renewables at record speed. The other is changing to a view of a romanticized past that never even existed as their own economics fall away.”

His comments followed rival Hancock Prospecting’s annual results on Thursday, when CEO Garry Korte warned that Australia could not afford the cost of reaching net zero.

Forrest dismissed the claim. “All I can say is that we’re seeing economic growth. We’re seeing investment … so trying to pedal yourself back to a utopian history which never existed anyway is not a way to grow an economy,” he said.

Mr President, Take Our Critical Minerals: Albanese in the White House

by Binoy Kampmark / October 28th, 2025

The October 20 performance saw few transgressions and many feats of compliance. As a guest in the White House, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was in no mood to be combative, and US President Donald Trump was accommodating. There was, however, an odd nervous glance shot at the host at various points.

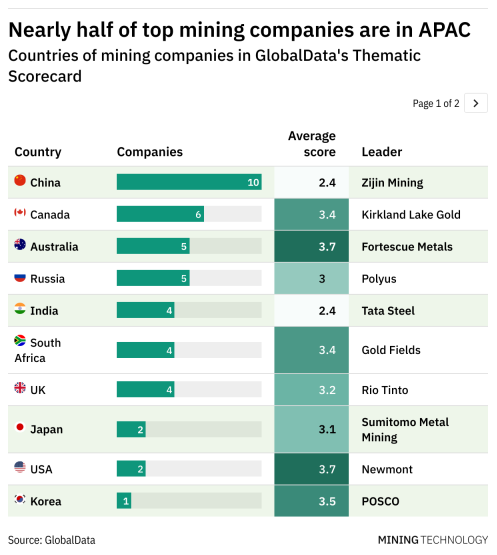

The latest turn of events from the perspective of those believing in Australian sovereignty, pitifully withered as it is, remains dark. In an attempt to seize a share of a market currently dominated by China, Albanese has willingly placed Australia’s rare earths and critical minerals at the disposal of US strategic interests. The framework document focusing on mining and processing of such minerals is drafted with the hollow language of counterfeit equality. The objective “is to assist both countries in achieving resilience and security of minerals and rare earths supply chains, including mining, separation and processing”. The necessity of securing such supply is explicitly noted for reasons of war or, as the document notes, “necessary to support manufacturing of defense and advanced technologies” for both countries.

The US and Australia will draw on the money bags of the private sector to supplement government initiatives (guarantees, loans, equity and so forth), an incentive that will cause much salivating joy in the mining industry. Within 6 months “measures to provide at least $1 billion in financing to projects located in each of the United States and Australia expected to generate end product for delivery to buyers in the United States and Australia.”

The inequality of the agreement does not bother such analysts as Bryce Wakefield, Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Institute of International Affairs. He mysteriously thinks that Albanese did not “succumb to the routine sycophancy we’ve come to expect from other leaders”, something of a “win”. With the skill of a cabalist, he identified the benefits in the critical minerals framework which he thinks will be “the backbone for joint investment in at least six Australian projects.” The agreement would “counter China’s dominance over rare earths and supply chains.”

Much of what was agreed between Trump and Albanese was barely covered by the sleepwalking press corps, despite the details of a White House factsheet. There were more extorting deals extracted from Canberra, with agreements to purchase US$1.2 billion in Anduril unmanned underwater vehicles and US$2.6 billion worth of Apache helicopters. Of particular significance was the agreement to push Australia’s superannuation funds to increase investments in the US to US$1.44 trillion by 2035, which would increase the pool by US$1 trillion. “This unprecedented investment will create tens of thousands of new, high paying jobs for Americans.”

Back in Australia, attention was focused on other things. The mock affair known as the opposition party tried to make something of the personal ribbing given by Trump to Australia’s ambassador to the United States, Kevin Rudd. Small minds are distracted by small matters, and instead of taking issue with the appalling cost of AUKUS with its chimerical submarines, or the voluntary relinquishment of various sectors of the Australian economy to US control, Sussan Ley of the Liberal Party was adamant that Rudd be sacked. This was occasioned by an encounter where Trump had turned to the Australian PM to ask if “an ambassador” had said anything “bad about me”. Trump’s follow up remarks: “Don’t tell me, I don’t want to know.” The finger was duly pointed at Rudd by Albanese. “You said bad?” inquired Trump. Rudd, never one to manage the brief response, spoke of being critical of the president in his pre-ambassadorial phase but that was all in the past. “I don’t like you either,” shot Trump in reply. “And I probably never will.”

This was enough to exercise Ley, who claimed to be “surprised that the president didn’t know who the Australian ambassador was”. This showed her thin sheet grasp of White House realities. Freedom Land’s previous presidents have struggled with names, geography and memory, the list starting with such luminaries as Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. Not knowing the name of an ambassador from an imperial outpost is hardly a shock.

The Australian papers and broadcasters, however, drooled and saw seismic history in the presence of casual utterance. Sky News host Sharri Markson was reliably idiotic: “The big news of course is President Trump’s meeting with Albanese today and the major news story to come out of it is Trump putting Rudd firmly in his place.” Often sensible in her assessments, the political columnist Annabel Crabb showed she had lost her mind, imbibing the Trump jungle juice and relaying it to her unfortunate readers. “From his humble early days as a child reading Hansard in the regional Sunshine State pocket of Eumundi, Kevin Rudd has been preparing for this martyrdom.”

Having been politically martyred by the Labor Party at the hands of his own deputy Julia Gillard in June 2010, who challenged him for being a mentally unstable, micromanaging misfit driving down poll ratings, this was amateurish. But a wretchedly bad story should not be meddled with. At the very least, Crabb blandly offered a smidgen of humour, suggesting that Albanese, having gone into the meeting “with the perennially open chequebook for American submarines, plus an option over our continent’s considerable rare-earths reserves” was bound to come with some human sacrifice hovering “in the ether.”

In this grand abdication of responsibility by the press and bought think tankers, little in terms of detail was discussed about the next annexation of Australian control over its own affairs by the US. It was all babble about the views of Trump and whether, in the words of Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, Rudd “did an extremely good job, not only in getting the meeting, but doing the work on the critical minerals deal and AUKUS”. For the experts moored in antipodean isolation, Rudd had either been bad by being disliked for past remarks on the US chief magistrate, or good in being a representative of servile facilitation. To give him his due, Wakefield was correct to note how commentators in Australia “continue to personalise the alliance” equating it to “an episode of The Apprentice.”