Unpacking working-class reaction

First published at Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

The ascent of the far right has become a commanding fact of European political life in the past four decades. Since 1989, far-right parties have increased their median vote share by almost 20 percent, while the previous decade has seen them graduate into plausible contenders for government from Poland to France. The latter trend arguably began in Central Eastern Europe in the early 2010s with the election of Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Andrej Duda in Poland, quickly spreading to the Western half of the continent with upsets for far-right parties in Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, among others. Although its ascent is by no means uniform, the momentum, at least for now, seems firmly on their side.

Currently arrayed across three different camps on the European level, perhaps most remarkable about these new far-right forces is their seeming ability to draw working-class support in a way historical fascist and reactionary parties could not. This fact raises difficult but vital questions for any left project in Europe, both now and in the future. How can the new proletarian swing to the right be understood, and more importantly, can it be reversed?

Marxism hardly is an analytical novice to this question. Stuck in American exile in 1941, the Marxist theorist Karl Korsch surveyed the successes of Hitler’s blitzkrieg on Crete and tried, heroically, to offer a class-conscious interpretation. The German offensive, he wrote in a letter to Bertolt Brecht, expressed “frustrated left-wing energy” and a displaced desire for workers’ control. Decades later, Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt summarized Korsch’s position with reference to the historical background of the German battalions:

. . . in their civilian life, the majority of the tank crews of the German divisions were car mechanics or engineers (that is, industrial workers with practical experience). Many of them came from the German provinces that had experienced bloody massacres at the hands of the authorities in the Peasant Wars (1524–1526). According to Korsch, they had good reason to avoid direct contact with their superiors. Almost all of them could also vividly remember the positional warfare of 1916, again a result of the actions of their superiors, in whom they had little faith thereafter . . . According to Korsch, it thereby became possible for the troops to invent for themselves the blitzkrieg spontaneously, out of historical motives at hand.

Although analytically far-fetched, it is tempting — and consoling — to view the ascendance of Europe’s extreme right through a similar lens. Both new and old provinces conquered — Thuringia, Billancourt, East Flanders, or the suburbs of Vienna — were labour movement strongholds in the twentieth century. There, the old demand for workers’ control seems to have been diverted into xenophobic passion, a longing to overthrow the bourgeois regime replaced by an attempt to smash its weakest subjects. One wants to believe, as did Korsch, that behind the mask of reaction there is still some potentially emancipatory profile, that a left-wing edifice can be rebuilt on the ruins.

Switching sides?

A sizeable body of social-scientific literature built up since the early 1990s, when the European far right achieved its first breakthroughs on the continent, also seems to sanction such a Korschian reading. Together with a growing literature on populism, a “switching thesis” implied that, with the onset of a new, post-industrial society, the European working classes steadily left their abode in Communist and social-democratic parties and migrated to the opposite end of the political spectrum. As Korsch would put it, they deposited their “left-wing energy” elsewhere, in a felicitous convergence of extremes which liberal writers had already detected in the totalitarianisms of the twentieth century.

The thesis continued to haunt political discourse throughout the long 1990s and, with the far right increasingly taking on a social and even anti-European slant, attained a plausibility far beyond the confines of the academe alone. It even led some figures to dub new far-right outfits from the Front National to Jörg Haider’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) workers’ parties, or assign them the title “populist” — still a relatively new addition to the social science vocabulary in the early 1990s.

Its limits were clear to see. Even if it captured some of the rhetorical features of the new far right, which had traded an emphasis on racial identity for cultural specificity, the term all too often allowed them to suppress tainted associations with a post-fascist tradition, and often turned them into freshly appointed stewards for a working class abandoned by its left-wing representatives. At the same time, the term “populist” undoubtedly owed its attraction to the novelty of some of these parties. With no clear military wings and not populated by frustrated veterans, they were hard to compare to their fascist progenitors. Their popularity was driven by the structural decline of party power across Europe, in which voters abandoned their traditional party outfits and joined a newly virtual and undetermined “people”, easily seduced by forces further on the right of the spectrum.

The switching thesis was always more than an analytical device, however. Steadily, it mutated into a fully-fledged political programme, in which left-wing parties were asked to either adjust to and learn from far-right parties, or scout for a new popular base, situated in a new middle class or an increasingly diverse service-sector proletariat. Since their old electorate had left, a new one had to be found. With terms such as “gaucho-lepenisme” or a “red-brown” politics, this literature thereby not only supported a populist interpretation of the new far right; it also beckoned the Left to move rightwards, following the lead of its own ex-electorate and apostles of concern in the commentariat.

Today, the consequence of this switching politics is become even clearer, as establishment conservatives use the notion as an alibi to move further rightwards, while parts of the Left either seek to regain a lost working-class electorate by copying tactics further on the right, or let go of its peripheral constituency altogether.

Yet there was no shortage of critiques of this switching thesis by the early 1990s. They noted that many of the regions now counted as new right strongholds saw higher rates of abstention than others. They insisted that voters who left workers’ parties did so out of a disappointment with the market transitions of the 1990s and 2000s — only faintly captured by the notion of “globalization” — and not out of an ineradicable hatred of foreigners. Critics also insisted that the ties these new voters held with the far right were hardly comparable to the integral social worlds previously offered to them by parties on the Left. The online chat group was not the casa del popolo, and, most importantly, the far right’s social programme lacked any ambition to tackle the growing power of capital.

The result was a twenty-first-century version of the “ecological fallacy” in fascism scholarship: the idea that working-class regions voted fascist in fact obscured the reality that the middle classes in those regions voted fascist, not the working classes themselves, who were always an envious absence from fascist party rolls. Rather than a working-class shift to the right, many exurban workers simply dropped out of politics altogether. Although sections of their class and the new petty bourgeoisie did make a move to the far right — partly out of fear of labour market competition, partly out of xenophobia — they did so hardly as a collective, class-conscious entity.

Fascization without mobilization

The last years have only increased the attractiveness of the switching thesis. In former East Germany, France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, the existence of a growing working-class vote no longer reducible to abstentionism seems undeniable. The interpretative war around this vote has been equally strident. Many insist that the rise of the far right should not be understood as wrongly sublimated left-wing libido, as Korsch had it, but as an expression of late-capitalist rot — not an insurgency to be redirected, but an impulse to be quashed.

The essentials of much of this diagnosis are often inarguable: that the class composition of the new far-right voter is not homogenously proletarian, that they are often not responding to events representing any concrete “immigrant threat”, that their actions were incited by both the political class and a growing army of far-right social media entrepreneurs, and that Europe’s rightward lurch owes more to feverish media speculation than to the authentic grievances of the dispossessed. Rather than “concerned citizens”, this critique claims, the base of the new far right consists of revanchist lumpen and middle classes unable to cope with the fact of social change in the twenty-first century. A literature on “neo-fascism” or “late fascism”, represented by authors such as Alberto Toscano and Enzo Traverso, has sought to place the revenge fantasies of the contemporary far-right in this frame, showing how new settings summon old ghosts.

Yet while the word “populist” proves of highly limited use when understanding the new right, the term “fascist” will undoubtedly prove equally constraining. In terms of the favoured ideologemes — from Great Replacement to other ethnonationalist fantasms — the continuity with the twentieth century is hard to deny. In politics as in biology, environment often proves as important as heredity, as the historian Christopher Hill once noted, and contemporary fascists must contend with parameters incomparable to those of their ancestors. These include demilitarization and the absence of a pre-revolutionary threat from the Left. As Dylan Riley has noted, the peculiarity and the specificity of the contemporary far right becomes clear when contrasted with the fact that, traditionally, fascists never were able to retain any solid working-class support — a point of incessant frustration to many far-right cadres.

Europe’s fascists, for one, rose to power in a period of intense social confrontation: Hitler and Mussolini both prevailed after workers’ movements tried to instigate revolutions, and were seen by elites as their best chance to stabilize the social order and re-establish labour discipline. A muscular proletariat is conspicuously absent from the European scene today, fatally weakened by deindustrialization and loose labour markets. In contrast to the 1930s, when fascist street violence flourished, the contemporary far right thrives on demobilization, both electorally and non-electorally.

For instance: Meloni’s party won a majority of votes in an election in which nearly four out of ten Italians stayed home, with turnout down by almost 10 percent. In France, Le Pen’s National Rally has long received its best tallies in parts of the country with the highest voter abstention rates. In Poland, the Kaczynski family behind the Law and Justice party ruled over a country where fewer than 1 percent of citizens are members of a political party.

These are not mass affairs, but rather exercises in orchestrated passivity that hardly tolerate comparisons with twentieth-century mass parties. As David Broder has noted for the Italian case, while “the latest advance for a far-right party in the land of Fascism’s birth surely lends itself to evocative analogies”, this “does not mean that Mussolini’s heirs merely repeat the past in the present, or even that the fascist elements of their culture are always drawn from interwar Italy.”

The data indicate the deeply contemporary character of the Europe’s extreme right surge — the outgrowths of a newly networked radicalism, not a return to Freikorps militancy or Boulangist militarism that seeks catch-up colonies in the east. Hitler and Mussolini promised to forge colonial empires of the kind their French and British competitors had acquired long ago. Their ambition was to break down borders, not to reinforce them. Today’s far right, by contrast, seeks to shield the Old World from the rest of the globe, conceding that the continent will no longer be a protagonist in the twenty-first century, and that the best it can hope for is protection from the postcolonial hordes.

Where does this leave us for an anatomy? As mentioned, both the copycats and the deniers — one seeking to emulate far-right success in working-class sectors, the other abandoning the terrain — face the same problem. The switching thesis has some empirical support, yet it proportionally includes more normative commitment than sober scientific analysis. In terms of support for the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) or even the Western extreme-right vote in general, what is far more striking is its dependence on demobilization rather than remobilization: most working-class voters drop out of politics while some of them migrate to the extreme right, and this small set of defectors is then made to stand in for the entirety of the demobilized class.

Demobilization thus gets mistaken for remobilization — working-class voters are experimenting with new parties, but the main response is a mixture of apathy and retreat, not rebellious defection. Even those voters who migrate to the Right, thereby feeding the optical illusion of a general switch, usually have much weaker ties with those new extreme-right parties than they used to have with their previous left-wing outfits (a pattern clearly visible in the North of France, where Le Pen has taken former Communist strongholds, and in eastern Germany). There, the vote for the extreme right is a secretive, private, individual affair, not an explicit engagement — more passive-aggressive than active, more informal than formal.

Didier Eribon noted in his memoir of his ex-Communist parents, his father’s migration to the extreme right also had to be expressed in a different register from the Communist lifestyle he had adhered to before. “Unlike voting communist, a way of voting that could be assumed forthrightly and asserted publicly”, his father’s new vote “seems to have been something that needed to be kept secret, even denied in the face of some ‘outside’ instance of judgment.” In contrast to the Communist Party, in “voting for the National Front, individuals remain individuals and the opinion they produce is simply the sum of their spontaneous prejudices”, an act carried out in the enclosure of the ballot box.

Dimensions of reaction

Two poles inherent in the switching thesis can therefore be avoided: presenting the new far right as a supposedly authentic expression of working-class grievances, abandoned by an overly progressive Left, or depicting it as an exclusively middle-class and elite outfit which only simulates its proletarian base. Similarly, a middle way between economism and culturalism stops short from reducing the far-right surge to a proletarian rebellion or claiming that its voters somehow hallucinate the fact of socio-economic decline.

Conversely, Europe’s extreme-right surge is thus no twisted expression of “material interests”, but this should not lead us into a form of superstructuralism that represses the economic roots of the current crisis. While a Korschian outlook can lapse into lazy apologism, there is also a species of anti-economism that risks obscuring the social terrain and thereby relinquishing the prospect of changing it. To understand the flammable environment at which Europe’s pyromaniac far right has taken aim, we need less mass psychology and more political economy. Here, the new right is, at its core, an attempt to rhetorically manage and contain the contradiction at the heart of European financialization: an economy dependent on cheap labour for its meagre growth rates, unable to deliver meaningful productivity, with a population that increasingly wants the state to mount some kind of systemic intervention.

One particular factor of neglect is how economic factors underpin the peculiarly schizoid status of immigration in European public life. A cheap supply of labour remained essential in the wake of partial deindustrialization in the 1990s and 1980s, as demographic expansion became necessary to sustain the rising service sector and help European industry retain competitiveness on an increasingly hostile world market. Despite all its rhetorical bombast, conservative parties have done little to alter these fragile growth models in the last decades. For instance: the British Conservative Party did not reduce immigration figures over the last decade, nor articulate even the mildest equivalent of Bidenist “reshoring”, while its base has increasingly been swept up in anger.

Popular dissatisfaction has meanwhile been rising since at least the late 2000s, with a creeping sense in the lower ends of the labour market that even if immigration does not cause low wages, it remains an indispensable part of the low-wage regime to which the British policy elite is committed. What we have witnessed in recent years is the explosion of that discontent, in Britain and elsewhere, in the “hyperpolitical” form that dominates the 2020s: agitation without durable organization, short-lived spontaneism without institutional fortress-building. With a new flock of influencers on the far right, these “trigger points”, as Steffen Mau and his researchers call them, can easily get charged.

There is an inevitably international dimension to the current rise of domestic xenophobia, as well. Is it surprising that nations that style themselves as attack dogs for a declining imperial hegemon, and unconditionally support an ongoing genocide in the Middle East, would see such belligerence ricochet back onto the home front? Both the UK and Germany, having normalized and repeatedly defended the ongoing war crimes in Palestine, have given a strong impetus to those wishing to enact anti-Muslim violence here at home.

Unlike the dominant varieties of antisemitism, anti-Islamic sentiment does not usually engage in projections of global omnipotence. It casts the Muslim as a dangerously ambiguous figure. In the zero-sum world of late capitalism, their ability to retain a minimum of communal cohesion is seen to have better equipped them for labour market competition. Rather than a fear of the other, anti-Muslim feeling is a fear of the same: someone in a position of equal dependence on the market, yet who is thought to be more effective in shielding themselves against its onslaught. At the same time, the Muslim is also seen as a subaltern agent of the abstraction which finance has inflicted on the worlds of post-war stability: someone who is out of place, who is causing “borders and boundaries to erode”, as Richard Seymour puts it.

Breaking through

In 1913, Lenin controversially claimed that behind the Black Hundreds, the reactionary monarchist force which first gave the world the notion of “pogromism”, one could detect an “ignorant peasant democracy, democracy of the crudest type but also extremely deep-seated”. In his view, Russian landowners had tried to “appeal to the most deep-rooted prejudices of the most backward peasant” and “play on his ignorance”. Yet “such a game cannot be played without risk”, he qualified, and “now and again the voice of the real peasant life, peasant democracy, breaks through all the Black-Hundred mustiness and cliché”.

There is no repressed emancipatory core to Europe’s extreme right surge, no “energy” which can be recuperated. In this sense, the kind of desperate hope that Korsch read into the blitzkrieg should be abjured. But underneath the rise of the continental right still lies a universe of misery which it is the Left’s historic task to negate — and sometimes, as Lenin noted, the voice of the post-industrial peasant breaks through all the “mustiness and cliché”.

More dangerously, successful strategies for doing so are in short supply and often more palliative than oppositional. A-to-B marches, the kind that are now taking place in many European cities every month, can be a useful way to assert a political line and remain a minimum requirement of any politics that would stop the far right. But they are inadequate to occupy the deep social void being seized upon by Europe’s new far right.

Anton Jäger is a Belgian historian of political thought who teaches politics at Oxford.

The far right: A reactionary backlash

First published in Spanish at Revista Contexto. Translation from Transform Network.

I’ve been reading analyses of the far right for years, without finding one that really offered the key to understanding why these forces have so much support. That was until the last few months, when I read a study in the Financial Times, an old feminist book, and a journal article by two historians. Together, they prompted me to think about the answer that — in a nutshell — I intend to set out here.

The rise of the far right is not an expression of political discontent, nor a social pathology, nor still less an expression of anti-systemic feeling. The growth of the far right in the last decade is a backlash — and, moreover, a global backlash. But a backlash against what? Against a shifting of the terrain.

History has changed

Some academic historians have argued that the most profound change resulting from the acceleration of globalisation is the transformation of the concept of History itself — and that this has much to do with the rise of the far right. I am greatly impressed by their argument.

They explain that world history has tended to be studied and taught as a linear history, a series of stages (which even have names and start- and end-dates) through which humanity moves forward, towards ‘progress’. Because of the European empires, History has been understood as Western history, a tree in whose top branches are the developed nations (the great powers, the empires) led by elite white men who are the masters of technology and of the vision of progress (‘civilisation’, it used to be said), whereas lower down are the nations on the path set out by that model of development, and all the other subaltern groups.

These new historians — whose thinking is described in the article by Hugo and Daniela Fazio which I am suggesting to readers — point out that this concept of history is now unsustainable. The rise of Asia, especially China, is deconstructing this idea of Western history. But it is also deconstructed by the emergence of feminism and anti-racism, with its decolonial message, which have brought a shift away from this vision of History in favour of a much more global and diverse one. They have baptised History as a global history, and done so on the basis of a precious truth, which will be self-evident for those without gender or class blindness: Today, subaltern groups that have been under-represented or made invisible in contemporary history are bursting onto the scene, making new demands with new leaderships and epistemologies, as the myth of the West is dislocated in favour of a much more diverse world.

This displacement generates resentment among those who think that they are losing their privileged position, in a world that no longer sees them as an authority and thus challenges their position of power. The far right is just that: backlash by those who are losing their privileges, or fear losing them. The feeling that it manipulates is resentment: Not anger, not rage, not political disenchantment, but a resentful victimisation, the appeal to the wounded narcissism of those who feel they have lost their leading role in history, at home, or in the workplace. The rise of militarism and war are part of this violent reaction against a world that is shifting the terrain underneath them, and against the wave that is dislodging them from their position.

The fourth wave

One feminist book that had a huge impact in the 1990s was Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. Its author Susan Faludi denounced the conservative backlash against women’s advancement in those years — insightfully pointing out that this backlash was not because women had achieved full equality, but because ‘it was possible for them to achieve it’. Faludi’s book helped me to understand that the rise of the far right is a reaction, first and foremost (though not only, against the fourth wave of feminism. I assure you: the data is irrefutable.

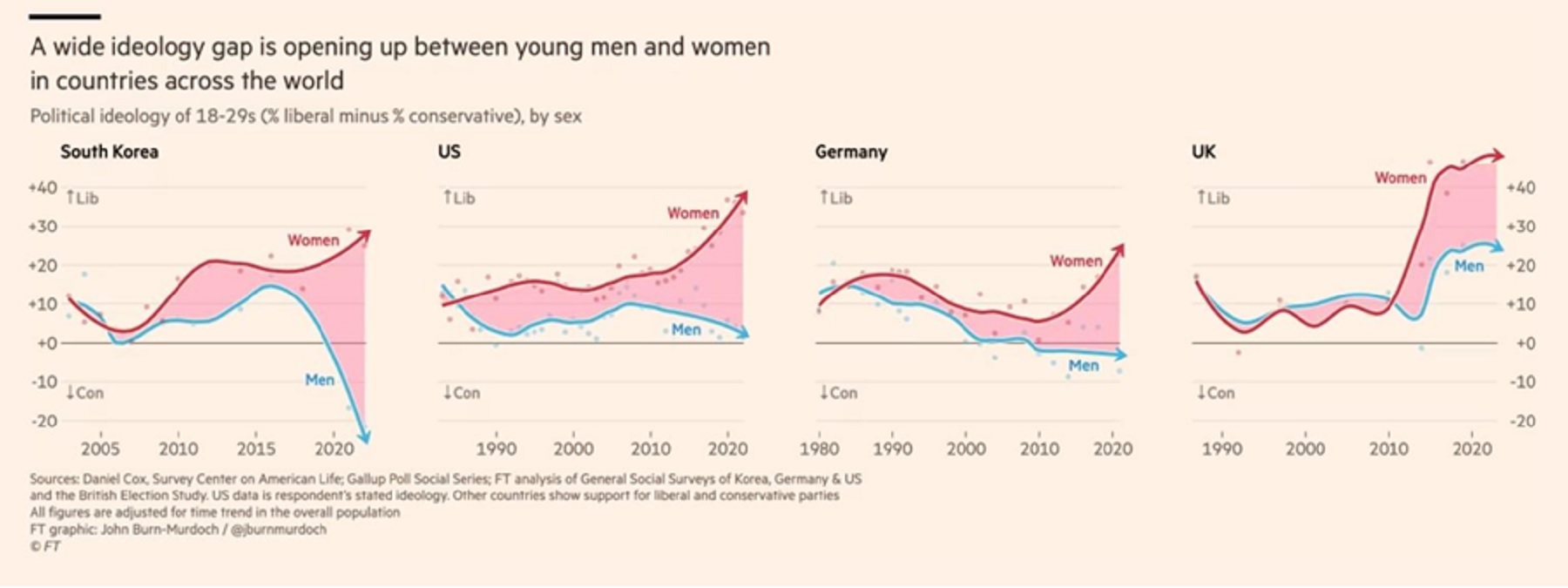

This 25 January, the Financial Times published a study that made the heads of many analysts of the far right explode. The article showed the youth vote by gender in South Korea, the US, Germany and the United Kingdom. It concluded that there is a yawning gap between the political attitudes of young women (who are far more progressive) and young men (who are more conservative and more likely to support the far right). The most shocking thing is that this is a global phenomenon, happening all over the world — including in Spain:

The strangest attempts are made to rationalise all this, often leaving me amazed. They range from claims that women are more ‘moderate’ to the idea that we have ‘less contact with migration’, and other such nonsense. It is obvious, without the gender blindness that pervades academia, that this is the consequence of the fourth wave that has swept the world. When it emerged, almost a decade ago, it did so globally, as a mass movement, expressed through social networks and with a strong intergenerational component.

This is, moreover, a feminist wave that has been more anti-capitalist than previous ones; a feminism that disarms the historical role of patriarchy and has won the battle for the aspiration of equality. The far right is a violent reaction to this displacement, to this dethroning of the pater familias, the dominant male, the maker of history.

Here I think it worth observing that many analyses reduce machismo and racism to moral, cultural attitudes — refusing to reckon with the fact that both constructs are used in capitalism to exploit us further. The self-evident fact that women and migrants are cheaper, indeed all over the planet, doesn’t seem to make a dent in their analysis. They have to go to great lengths to deny the data and continue to insist that women and migrants are minorities and treat us as such, even when the reality is quite the opposite. I almost admire their stubbornness.

I may be wrong, but I sense, moreover, that the analytical blindness is not only gender-based. I detect a stubborn reluctance to accept that there is no direct relationship between economic inequality and the growth of the far right; in other words, economic orthodoxy does not serve to analyse the phenomenon. If this were the case, there would be no way of explaining its success in Scandinavian countries (the least unequal in the world) or the fact that in the country where inequality is most glaring, South Africa, the far right does not even exist. Of course, the economic situation may be a trigger for the growth of the far right, but it is not its cause.

It seems that cold economistic metrics don’t grasp resentment — and resentment is the sentiment that drives backlash. To understand this better, I suggest reading the superb study by Tereza Capela et al. on Korean far-right youth, which concludes, decisively, that their attitudes are exclusively built on resentment and victimisation.

Reactionary whispers

I smell, with trained senses, a certain tendency (from which not even the European left is free) to appease some of the claims of the far right, in the face of the threat that they pose. This is itself a global phenomenon. I am beginning to hear, subtle as a whisper, that perhaps we feminists have gone too far, that we ought to pay more attention to the demands of these young men who are turning to the right, that immigration is a problem, that what’s happening in Palestine is not genocide, that we need to buy more weapons, that the climate crisis is not so fundamental…

I would argue the opposite. The antithesis to the far right — its nemesis — is precisely the defence of feminism, especially of young women and their demands, the concept of class versus nation, the defence of peace, diversity, equality, social justice, solidarity, ecology, and a common world. We must defend them, moreover, with an outlook that overcomes the narrow and hierarchical worldview of the West.

I would argue that the far right is a backlash against the energies with which we subalterns are starting to change the world. But I would also warn — to echo Susan Faludi — that this is backlash not only against change that has taken place already, but also against the possibility of future change. They are reacting violently to change, in order to prevent it from occurring. And that is what the far right is: pure reaction.

Marga Ferré is co-president of Transform Europe.