The Nazi Origins of the South American Drug Trade: Klaus Barbie, Cocaine and the CIA

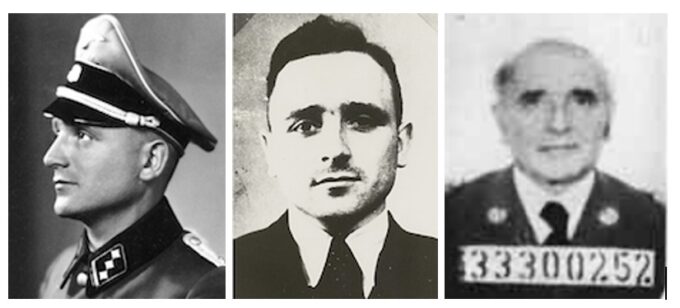

The three faces of Klaus Barbie.

Personally, I have no regrets. If there were mistakes, there were mistakes. But a man has to have a line of work, no?

– Klaus Barbie

By the time Klaus Barbie went on the payroll of an American intelligence organization in 1947, he had lived several lifetimes of human vileness. Barbie sought out opponents of the Nazis in Holland, chasing them down with dogs. He had worked for the Nazi mobile death squads on the Eastern Front, massacring Slavs and Jews. He’d put in two years heading the Gestapo in Lyons, France, torturing to death Jews and French Resistance fighters (among them the head of the Resistance, Jean Moulin). After the liberation of France, Barbie participated in the final Nazi killing frenzy before the Allies moved into Germany.

Yet the career of this heinous war criminal scarcely skipped a beat before he found himself securing entry on the US payroll in postwar Germany. The Barbie was shipped out of Europe by his new paymasters along the “ratline’ to Bolivia. There, he began a new life remarkably similar to his old one: working for the secret police, doing the bidding of drug lords and engaging in arms trafficking across South America. Soon, his old skills as a torturer became in high demand.

By the early 1960s, Barbie was once again working with the CIA to put a US-backed thug in power. In the years that followed, the old Nazi became a central player in the US-inspired Condor Program, aimed at suppressing popular insurgencies and keeping US-controlled dictators in power throughout Latin America. Barbie helped organize the so-called “Cocaine Coup” of 1980, when a junta of Bolivian generals seized power, slaughtering their leftist opponents and reaping billions in the cocaine boom, in which Bolivia was a prime supplier.

All this time, Klaus Barbie was one of the most wanted men on the planet. Even so, Barbie flourished until 1983, when he was finally returned to France to face trial for his crimes. In the whole sordid history of collusion between US intelligence agencies, fascists and criminals, no one more starkly represents the evils of such partnerships than Klaus Barbie.

+++

On August 18, 1947, three men sat over drinks in a café in Memmingen, part of American-occupied Germany. One was Kurt Merck, a former officer in Nazi Germany’s military intelligence agency, the Abwehr. Merck had worked in France during the war and had been scooped up by American intelligence, who debriefed him and soon put him on the payroll. The second man was Lieutenant Robert Taylor, an American officer in the Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC). The third man was Klaus Barbie, at that time on the run from the French and the Soviets, and number three on a US/British list of wanted SS men. Barbie had already been roughly interrogated by the British and did not care to repeat the experience.

Merck was an old friend of Barbie’s. Despite interservice rivalries between the Gestapo and the Abwehr, the two had worked together in France and had gotten along well. Merck was more than willing to vouch to the American officer that Barbie would be a good hire. Merck had been recruited by the Counter-Intelligence Corps in 1946, at a time when US intelligence agencies were trying to recruit Nazi talent. CIC’s cover story for this unwholesome bit of head-hunting was the need to root out and suppress a supposed network of Hitler Youth, whose fanatical detachments had pledged to fight on, no matter what official terms of surrender had been signed.

But CIC’s real interest in Barbie had nothing to do with the so-called Werewolves of the Hitler Youth. Barbie’s hiring as an agent of the CIC was contingent on his willingness to impart information about British techniques of interrogation and about the identities of SS men the British might have tried to recruit as their own agents. Barbie was only too happy to comply, particularly as this enthusiastic torturer had been slightly bruised when he was questioned by the British.

For the next four years, the third most wanted SS man in Germany worked for the US Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps. The Americans set up Barbie in a hotel in Memmingen, brought his family from Kassel and partly paid him in commodities–cigarettes, medicines, sugar and gasoline–that he sold for a handsome price on the black market. After initial debriefings about the intentions and techniques of the British, Barbie’s main assignment, as described in a CIC memo, was to file reports on “French intelligence activities in the French Zone and their agents operating in the US Zone.”

+++

By 1948, the French government had received information that Barbie was living under the protection of the US somewhere in Germany. The French were more eager than ever to get their hands on Barbie, who had already been sentenced to death in absentia for his war crimes. Barbie was needed to testify in the upcoming trial of René Hardy, the Resistance man who saved his own skin from Barbie’s torture by turning in Jean Moulin. But the CIC had no intention of handing over its prize catch to the French, even on loan for the Hardy trial.

Barbie’s handlers at the CIC, who saw the French as allies of Stalin, had nightmares about Barbie spilling the beans on his American employers. Eugene Kolb, the US Army Intelligence officer who had worked with Barbie for a year, said that the Gestapo man couldn’t be returned to the French because he “knew too much about our agents in Europe and the French intelligence agency was saturated with communists.” Kolb’s opinion is backed up by CIC memos, which suggest that the French Sûretė intended to “kidnap Barbie, reveal his CIC connections and embarrass the US.”

So it transpired that in December 1950, the US decided to trundle Barbie and his family down the ratline, an escape hatch from Europe for Nazi agents created by CIC officers Lt. Colonel James Milano and Paul Lyon. Lyon and Milano had been shuttling Nazis out of Germany, Austria and Eastern Europe since 1946, sending them to Argentina, Chile, Peru, Brazil and Bolivia. The tour guide for this operation was himself a war criminal, Father Krunoslav Draganovic, a Croatian priest who oversaw the relocation of several hundred thousand Jews from Yugoslavia to their deaths in Nazi concentration camps. As the fascist government in Croatia began to crumble at the end of the war, the priest made his way to the safety of the Vatican. Then Draganovic exploited the cover of his position with the Red Cross and with the Vatican and shuttled hundreds of war criminals out of Europe.

Many of Draganovic’s first recruits were members of the Ustaše regime, the death squads under the control of Croatian dictator Ante Pavelic, who supervised one of the bloodiest killing sprees of the war. Hundreds of thousands of Serbs–on some estimates more than two million–were slaughtered by Pavelic’s forces to fulfill his insane desire to make Croatia a “100 percent Catholic state.” Pavelic would show his favorite trophy to visitors at his office: a forty-pound jar of human eyeballs extracted from his Serbian victims. After the war, Draganovic helped Pavelic secure safe passage to Argentina, where he became a frequent dining companion of Juan and Eva Peron.

Some of the other notable Nazis who Draganovic helped escape Europe for South America included Colonel Hans Rudel, who went to Argentina, where he headed Peron’s air force and became a leader of the international neo-Nazi movement; Dr. Willi Tank, a chief designer for the Luftwaffe; and Dr. Carl Vaernet, who had overseen surgical experiments on homosexuals at Buchenwald, castrating gay men and replacing their testicles with metal balls. Vaernet was adored by the Perons, who showed their appreciation by making the Nazi doctor head of Buenos Aires’s public health department.

+++

In 1947, the Counter-Intelligence Corps contracted with Father Draganovic to help them dispose of some of their own problematic agents and recruits, namely Nazi scientists, doctors, intelligence operatives and engineers. The deal was brokered in Rome by CIC officer Paul Lyon, who noted that Draganovic had established “several clandestine evacuation channels to various South American countries for various types of European refugees.”

This priest, Draganovic was not an altruist, even on behalf of his Nazi colleagues. He demanded from the American intelligence agencies $1,400 for each war criminal who passed through his doors, and the US intelligence agencies were glad to pay his price.

A memo from an intelligence officer working at the US State Department explained that

the Vatican justifies its participation by its desire to infiltrate not only European countries, but Latin American countries as well, [with] people of all political beliefs, as long as they are anti-communists and pro-Catholic church.

Fearing that Barbie might slip through their fingers, the French protested directly to John J. McCloy, the US High Commissioner in Germany. McCloy icily replied that the US would not hand over Barbie to the French for possible execution, “because the allegations of the citizens of Lyons can be disregarded as being hearsay only.”

McCoy knew this to be untrue. In 1944, Barbie’s name was prominently displayed in McCloy’s own office on a list called CROWCASS (the Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects), where Barbie was identified as being wanted for “the murder of civilians and the torture and murder of military personnel.”

Barbie was hardly the only SS man whom McCloy and his cohorts endeavored to shield from justice. Another was Adolf Eichmann’s right-hand man, Baron Otto von Bolschwing. This former SS officer was hired by the CIC in 1945, where he swiftly became one of the agency’s most productive assets, recruiting, interrogating and hiring former SS officers. Von Bolschwing was later traded to the CIA, where he plied his tradecraft in East Germany. Like Barbie, von Bolschwing was a top-rank war criminal, having been one of Eichmann’s ideological gurus on Jewish matters, helping to script the plan to “purge Germany of the Jews” and rob them of their wealth. It was von Bolschwing who had directed one of the most vicious slaughters in the war, the murder of hundreds of Jews in Bucharest. The Bucharest pogrom is described in wrenching detail by historian Christopher Simpson in his remarkable book, Blowback. Simpson writes:

Hundreds of innocent people were rounded up for execution. Some victims were actually butchered in a municipal meat-packing plant, hung on meathooks, and branded as ‘kosher meat’ with red-hot irons. Their throats were cut in an intentional desecration of kosher laws. Some were beheaded. ‘Sixty Jewish corpses [were discovered] on the hooks used for carcasses,’ US ambassador to Romania Franklin Mott Gunther wired back to Washington after the pogrom. ‘They were all skinned… [and] the quantity of blood about [was evidence] that they had been skinned alive.’ Among the victims, according to eyewitnesses, was a girl no more than five years old, who was left hanging by her feet like a slaughtered calf, her body bathed in blood.

In 1954, von Bolschwing was brought to the United States. Richard Helms, who had helped recruit many of these criminals, defended the protection and use of people like von Bolschwing, saying: “We’re not in the Boy Scouts. If we’d wanted to be in the Boy Scouts, we would have joined the Boy Scouts”–a typically flippant way of rationalizing his recruiting practices.

Barbie’s Counter-Intelligence Corps handlers went to extraordinary lengths to protect their recruit. Eugene Kolb rejected the idea that Barbie might have physically tortured people on the grounds that he “was such a skilled interrogator, Barbie did not need to torture anyone.” In fact, it’s pretty clear that Klaus Barbie was a sadistic monster whose vocational priorities were the infliction of pain and ultimately death, rather than the subtle extraction of information.

Barbie’s expertise as a torturer relied on the use of bullwhips, needles pushed under fingernails, drugs, and, most uniquely, electricity sent by nodes attached to the nipples and testicles. His upward career path at the SS, heralded by games of volleyball with Heinrich Himmler in Berlin in 1940, came to an abrupt end when he beat Jean Moulin to death without getting any information out of him. Even so, a generation later, Barbie and his CIA operatives would happily cooperate in applying his old techniques to left oppositionists in Bolivia and elsewhere.

When it came to Barbie’s anti-Semitism, his American intelligence patrons once again sprang to his defense. Lieutenant Robert Taylor contended that Barbie “was not an anti-Semite. He was just a loyal Nazi.” Another CIC memo held that Barbie “showed no particular enthusiasm towards the idea of killing Jews.” In fact, Klaus Barbie got his start as an officer for the SD, a subunit of the SS charged by Reinhard Heydrich with solving the Jewish “problem” as rapidly as possible.

In an early purge in Holland, Barbie led the infamous raid on the Jewish farm village of Wieringermeer, where Klaus and his men used German shepherd dogs to round up 420 Jews, who were sent to their deaths in the stone quarries and gas chambers of Mauthausen.

From the training grounds of Holland, Barbie was transferred in July 1941 to the Eastern Front, where he joined one of the SS’s so-called “special task forces,” the Einsatzgruppen. These mobile killing squads were assigned the task of murdering every communist and Jew they could find in Russia and the Ukraine, without regard–in Heydrich’s chill phrase–“to age or sex.” In less than a year, these roving death squads under the command of men such as Barbie killed more than a million people. Here was the model for the CIA’s death squads in Vietnam–William Colby’s Phoenix Program and cognate operations– and in Latin America, where CIA-sponsored hit teams in Guatemala, El Salvador, Chile, Colombia and Argentina applied similar methods of brutal terror, killing hundreds of thousands. There’s nothing, in terms of ferocity, to separate a Barbie-run slaughter in eastern Russia from later operations at My Lai or El Mozote.

Montluc Prison in Lyons, France, where Barbie tortured Jewish prisoners.

Rewarded with a new promotion for his work on the Eastern Front, Barbie headed to Lyons in 1942. One of his tasks was to help fulfill Himmler’s recent order that the SS in France deport at least 22,000 Jews to concentration camps in the east. Barbie took up the task with enthusiasm. His crew raided the offices of the Union Générate des Israelites de France in Lyons, seizing records showing the addresses of Jewish orphans and other children hidden in the countryside. Later that day, Barbie arrested one hundred Jews, sending them off to their deaths at Auschwitz and Sobibor. Next, Barbie descended upon the Jewish orphans’ home at Izieu, rounding up forty-one children aged three to thirteen, along with ten of their teachers. All were trucked off to the Nazi death camps. Reporting on this raid of the schoolhouse to his supervisor, Barbie noted, “Unfortunately, in this operation it was not possible to secure any money or valuables.”

During his time in Lyons, Barbie was excitedly alert to the sufferings of the prisoners he held in Montluc prison. The SS man apparently derived a sadistic pleasure from locking his prisoners in cells for days at a time with the mutilated corpses of their friends. He would reassemble captured members of the French Resistance before mock firing squads, apply hot irons to the soles of their feet and palms of their hands, repeatedly plunge their heads into toilets filled with piss and shit and entice his black Alsatian dog, Wolf, to snap at their genitals.

Klaus Barbie’s torture of Lise Leserve was particularly horrific. He shackled her naked body to a beam and beat her with a spiked chain. But despite his “great skill” as an interrogator, Barbie never got Leserve to talk. She survived her torture and a year in Ravensbrück work camp to testify against him at his trial in 1984.

With the Allies advancing on Lyons, Barbie prepared to flee France in 1944. But before he left, he ordered the remaining 109 Jewish inmates of Montluc machine-gunned to death and had their bodies dumped in a bomb crater near the Lyons airport. Barbie also endeavored to wipe out the last of the French Resistance leaders under his control. On August 20, 1944, Barbie’s mean loaded 120 suspected members of the Resistance on covered lorries and drove them to an abandoned warehouse near St. Genis Laval. The prisoners were led into the building, where they were quickly machine-gunned. The mound of corpses was drenched in gasoline and the building was destroyed by phosphorus grenades and dynamite. The explosion sent body parts flying into town 1,000 feet away.

Such were the highlights on the resumé of the man who in 1951 was dispatched along with his family by US military intelligence to a Counter-Intelligence Corps safehouse in Austria. There, the Barbie family was given a crash course in Spanish and furnished with $8,000 in cash. Barbie was provided, courtesy of in-house forgers, with his new identity: Klaus Altmann, mechanic. In a sinister jest, Barbie picked the pseudonym “Altmann” himself, after the name of the chief rabbi in Barbie’s hometown of Trier. Rabbi Altmann had been one of the luminaries of the anti-Nazi resistance until 1938, when he went into exile in Holland, where he was tracked down in 1942 and sent to his death at Auschwitz.

From Vienna, the Barbies were passed via Draganovic’s ratline to Argentina and then on to Bolivia. A CIC internal memo triumphantly noted about the rescue of this war criminal that “the final disposal of an extremely sensitive individual has been handled.”

+++

Former CIA director Richard Helms, who recruited Nazis for the Agency, and defended its relationship with Klaus Barbie. Photo: White House.

On April 23, 1951, Klaus Barbie and his family arrived in La Paz, Bolivia, a city the young Che Guevara would later call “the Shanghai of the Americas.” Che, who visited La Paz in the summer of 1953, described it as inhabited by “a rich gamut of adventurers of all the nationalities.” Some of those adventurers, including Klaus Barbie, whom Che may have unwittingly passed on the streets or in the bars of La Paz, would, with the aid of the CIA, help track down and kill the revolutionary fifteen years later in the jungles outside Vallegrande.

Upon arrival in Bolivia, the Barbies were warmly embraced by Father Rogue Romac, another of Father Draganovic’s exiles. Romac’s real name was Father Osvaldo Toth, a Croatian priest wanted for war crimes. Toth helped Barbie establish a lucrative business destroying the Bolivian rain forest. The Nazi made a small fortune operating sawmills in the Bolivian jungles near Santa Cruz and lumber yards in La Paz. But Barbie soon became restless and could not long conceal his political ambitions. He was quickly drawn into the service of the proto-fascist government of Victor Paz Estensorro, where he consulted on internal security matters with with the Nazi exiles Heinz Wolf and a certain Herr Müller. Müller was a former Nazi prosecutor who had condemned to death the young leaders of the White Rose Resistance. Their crime: handing out anti-Nazi pamphlets at Munich University in 1943.

Barbie proved so useful to the Bolivian ruler that on October 7, 1957 he and his family wererewarded a highly sought prize: Bolivian citizenship, a status that would frustrate attempts to extradite him back to Europe. Barbie’s citizenship papers were personally signed by Bolivian vice president Hernán Siles Zuazo, who, many coups later, would be forced to relinquish Barbie to the French Nazi hunters. Barbie, however, had no particular loyalty to Paz Estensorro. Indeed, he soon found himself griping at a man whose bizarre political ideology merged leftist populism with fascist notions of social order. Barbie’s uneasiness with Paz Estenssoro was mirrored by similar grumblings in Washington. Paz Estenssoro had disappointed his American patrons on two touchstone issues: he maintained cordial relations with Castro’s government in Cuba and he refused to send the Bolivian military to crush striking tin miners. The CIA sent Colonel Edward Fox to La Paz to search for a candidate to replace Paz.

The man who won the CIA’s favor was General René Barrientos Ortuño. Barrientos was no stranger to Klaus Barbie. Indeed, they had been secretly plotting the overthrow of Paz for some time. The moment came in 1964 when the presidential palace was stormed and Paz was presented with a simple choice: he could “take a ride either to the cemetery or the airport.” Paz packed his bags and caught a plane to Argentina. The Barrientos coup returned Bolivia once again into the clutches of military dictatorship. But this time, the US government was taking no chances. It seized firm control of the Bolivian army, sending dozens of US advisers to La Paz and bringing 1,600 of Bolivia’s military officers back to the United States for training at American military bases. The group sent to the United States included twenty of Bolivia’s top twenty-three generals.

It was during this time that the French renewed their hunt for Barbie. They began to look for him in South America and sent repeated cables to the American government regarding Barbie’s whereabouts. The US denied any knowledge of its former agent, even though the CIA and other intelligence agencies were well aware that he had gone to work for the Barrientos regime.

Barbie secured a position in Barrientos’s internal security force, known as Department 4, where he planned counterinsurgency operations and instructed his underlings on Nazi techniques of interrogation and state terror. Barbie also used this position to put into play once more his ideology of political eugenics. This time his victims were Bolivian Indian tribes, whom he considered genetically and culturally inferior.

Barrientos and Barbie lost no time in going after the tin miners, executing a series of bloody raids by the army and Barbie’s secret police. Hundreds of miners and labor organizers were killed. Leaders of the union and of the opposition political party were forced into exile, dooming the tin mines, which were then the principal source of revenue for the Bolivian economy. Barrientos attempted to replace the lost revenue from the mines with oil profits, handing out huge concessions around the town of Santa Cruz to Gulf Oil. In return, Barrientos received what the company chastely termed “campaign contributions.” Gulf also presented Barrientos with a helicopter, a gift the company said was made at the instruction of the CIA. As we shall see, it was a present that would come back to haunt the general.

+++

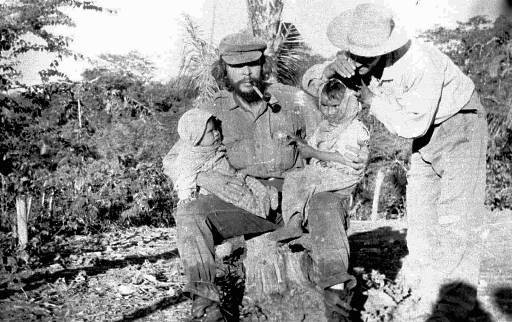

Che Guevara in Bolivia, 1967.

Revolutionary movements were multiplying across Central and South America and the CIA correctly feared that Bolivia, with its mixture of Indian peasants and radical labor groups, was ripe terrain for revolt. The CIA poured several million dollars into Bolivia during 1966 and 1967. Some of the cash, about $800,000, went directly into the pockets of Barrientos, no doubt making it easier for the general to tolerate the American takeover of his government. The CIA justified its presence in Bolivia in a 1967 memo: “Violence in the mining areas and in the cities of Bolivia has continued to occur intermittently, and we are assisting this country to improve its training and equipment.”

With a more stable and authoritarian regime in power, Barbie took the opportunity to expand his “financial empire. He started an enterprise called the Estrella Company, which sold quinine bark, coca paste and assault weapons. He also hooked up with Frederich Schwend, the SS’s financial whiz, who had ended up in Lima, Peru. Schwend had been sent to Latin America through the Nazi underground by the OSS after telling Allen Dulles where the SS had cached millions in cash, gold and jewels looted from its victims. Schwend claimed to be a chicken farmer, but in reality he was a high-paid consultant to generals in Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and Argentina.

The two Nazis also joined forces to create Transmaritania, a shipping company that was to generate millions in profits. Barbie shared the wealth by inviting onto the board of his company some of the heavy hitters of the Bolivian government, including the head of the Bolivian navy, the head of the joint chiefs of staff; and the head of the Bolivian secret police, General Alfredo  Ovando Candía. This shipping company began by handling flour, cotton, tin and coffee, but soon turned to much more profitable cargo: guns and drugs. The source for most of the weapons, including attack boats, tanks and fighter planes, marketed by Barbie and Schwend to regimes across South America was a Bonn-based company called Merex. Merex was controlled by another ex-Nazi taken on by the US: Colonel Otto Skorzeny, Hitler’s favorite stormtrooper and the man who had rescued Mussolini from prison. During the height of the Contra War, Oliver North’s operation would turn to Merex to consummate a $2 million weapons deal, thus underlining the essential continuity of Nazi alliances in US agencies from Army Intelligence to the OSS to the CIA to Reagan’s National Security Council.

Ovando Candía. This shipping company began by handling flour, cotton, tin and coffee, but soon turned to much more profitable cargo: guns and drugs. The source for most of the weapons, including attack boats, tanks and fighter planes, marketed by Barbie and Schwend to regimes across South America was a Bonn-based company called Merex. Merex was controlled by another ex-Nazi taken on by the US: Colonel Otto Skorzeny, Hitler’s favorite stormtrooper and the man who had rescued Mussolini from prison. During the height of the Contra War, Oliver North’s operation would turn to Merex to consummate a $2 million weapons deal, thus underlining the essential continuity of Nazi alliances in US agencies from Army Intelligence to the OSS to the CIA to Reagan’s National Security Council.

At least one of the people associated with Transmaritania was a CIA agent: Antonio Arguedas Mendieta, who served as minister of interior during the Barrientos regime and had been on the CIA’s payroll for many years when he entered into business with Klaus Barbie.

A year after Barrientos took power, Che Guevara vanished from the radar of the CIA. CIA director Richard Helms believed that the revolutionary had been killed after a supposed rupture with Fidel Castro following Che’s fiery public advocacy of a revolutionary line at a moment when Fidel was moderating his rhetoric. Helms was wrong. Che spent more than a year in the jungles of the Congo, helping orchestrate a revolutionary movement to oust the CIA-installed dictator Mobutu. Then in 1967 CIA agents in Bolivia had learned that Che was leading a revolution among the peasants in the Bolivian Andes. A detail squad of CIA officers and Green Berets were sent to La Paz. Four of the new advisers were Cuban veterans of the CIA’s previous plots against Che and Castro, including Aurelio Hernández and Fé1ix Rodriguez.

At this critical hour, the CIA once again sought out Barbie’s help. Acting through intermediaries in the Barrientos government, such as Ovando Candía and Arguedas, the Agency opened a conduit that would last through the 1970s with Barbie sending back a steady stream of information to his handlers at Langley. Barbie, given his close association with General Ovando Candía, almost certainly played a role in the tracking down and murder of Che Guevara.

In true Nazi fashion, General Ovando Candía demanded proof of Che’s identity after he had been shot on Barrientos’s orders. The general originally ordered that Che’s head be cut off and sent back to La Paz. Félix Rodríguez, the CIA man who had looted Che’s watch and a pouch of his pipe tobacco from his body, claims he persuaded the general that this might be counterproductive. Ovando relented, commanding instead that Che’s hands be amputated and embalmed. His body was buried near the airstrip at Vallegrande, and exhumed and returned to Cuba in 1997.

Ultimately, Che’s preserved hands and his diary ended up in the possession of Interior Minister (and CIA asset) Antonio Arguedas. But in 1968, Arguedas turned on the Barrientos regime, secretly releasing Che’s diary of his Bolivian campaign to the public and fled to Cuba with the guerrilla leader’s embalmed hands.

+++

In 1969, Barrientos died when his Gulf Oil helicopter crashed under suspicious circumstances. His death paved the way for General Ovando Candía’s short-lived presidency. Ovando’s government lasted less than a year before he was ousted in an election by the nationalist General Juan José Torres. Torres released Che’s comrades Regis Debray and Ciro Bustos from prison and made dangerous overtures to the Chilean government of Salvador Allende and to Castro’s Cuba. His government also seized lands owned by foreign corporations, including the lucrative mineral rights controlled by Gulf Oil.

This turn of events did not come as welcome news for the CIA, which had invested so heavily in Bolivia. Another coup was plotted. This time, the general of choice was Hugo Banzer Suárez, a man trained by the US military at Fort Hunt and at the Escuela de Golpes (the School of the Americas) in Panama. Banzer proved to be such a prize student that he earned the Order of Military Merit from the US military; he was also a longtime friend of Klaus Barbie, who was to play a crucial role in the coup.

The coup against President Torres culminated in August 1970, a week before President Torres was scheduled to journey to Santiago, Chile for a meeting with Salvador Allende. Even in Bolivia, the overthrow of the Torres government became known for its extreme violence and the lengths the new regime took to eradicate leftist elements in the country. Universities were shut down as “hotbeds” of radicalism, tin miners were once again violently suppressed, more than 3,000 leftists and union organizers were hauled in for interrogations and “disappeared.” The Soviet embassy was shut down, and relations with Cuba and Chile cooled. Gulf Oil was swiftly compensated for its seized properties.

Barbie defended the violent nature of the Banzer coup to Brazilian journalist Dantex Ferreira by saying that Torres’s leftist sympathies posed a threat to all of South America. “What Bolivia did in ’67 to defend herself against a coup by Che Guevara was also condemned in many parts of the world,” Barbie said.

For his role in helping to plot Banzer’s bloody takeover of Bolivia, Klaus Barbie was made an honorary colonel, and he became a paid consultant to both the Ministry of the Interior and the notorious Department 7, the counterinsurgency wing of the Bolivian army. Both institutions were thoroughly penetrated and funded by the CIA. Indeed, records from the CIA and the Bolivian government show that Barbie passed information to the CIA on suspected Soviet and Cuban agents in South America. He also sent back to Langley copies of documents he stole from the Peruvian embassy and information on the operations of the Chilean intelligence agency, DINA.

A Bolivian report on Barbie speaks glowingly of his service to the Banzer government:

One of the most important aspects of Barbie’s work was advising Banzer on how to adapt the military effectively for internal repression rather than external aggression. Many of the features of the Army, which were later to become standard, were first developed by Barbie in the early 1970s. The system of concentration camps … became standard for important military and political prisoners.

The Nazi also continued to advise the military’s secret police on methods of interrogating prisoners, which seem not to have evolved much since his days in Lyons. “Under Barbie, they [the Bolivian military] learned to use the techniques of electricity and the use of medical supervision to keep the suspect alive till they had finished with him.”

The Bolivian government paid Barbie $2,000 a month for his consulting services. But this was just a small portion of his take. He was also earning enormous profits from arms sales to the Bolivian military. Many of these purchases were paid for using funds provided by the US government, which was underwriting the cost of the Bolivian military.

+++

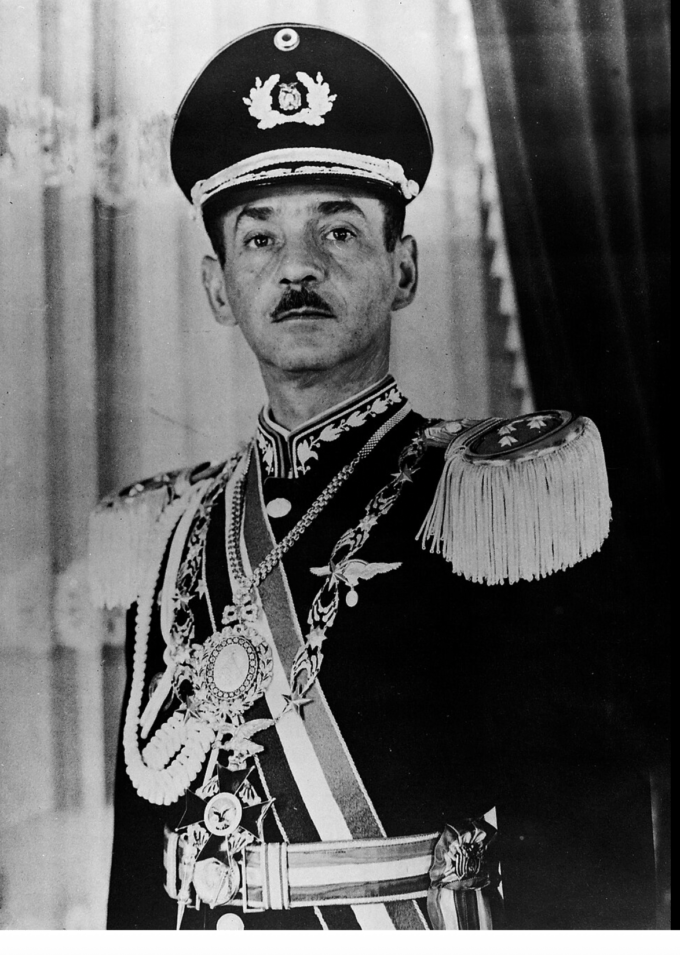

Hugo Banzer Suarez, the cocaine-running, coup-installed, CIA-backed president of Bolivia, who made Klaus Barbie, who put Barbie on retainer, gave him a cut of the cocaine trade and bought weapons from his arms company.

The 1970s were a heady time for Barbie. He lectured widely on the new South American fascism, often at candlelight vigils in so-called Thule halls adorned with Nazi flags and other iconography from the Third Reich. The war criminal also traveled freely. During the late 1960s and 1970s, Barbie visited the US at least seven times. Incredibly, he also journeyed back to France, where he claims to have laid a wreath on the tomb of Jean Moulin.

Catholic missionaries and priests were one of the groups that Barbie and Banzer went after with particular zeal, since Banzer believed that they had “become infiltrated with Marxists.” Priests were hauled in for interrogation, harassed, tortured and killed. One who was murdered was an American missionary from Iowa named Raymond Herman. This repression campaign against liberationist clergy became known as the Banzer Plan, and it was enthusiastically adopted in 1977 by his fellow dictators in the Latin American Anti-Communist Confederation. This crackdown was also backed by the CIA, which provided information to Barbie’s men on the addresses, backgrounds, writings and friends of the priests. Barbie also was at the heart of the US-sponsored Condor Operation, a kind of trade association of South American dictators, who merged their forces in an effort to stamp out insurgencies wherever they broke out on the continent.

Banzer’s startling consolidation of power was backed by millions from two friends, the German-born industrialist Eduardo Gasser and the cattle rancher Roberto Suárez Gómez. But Suarez also had another business. He oversaw one of the world’s most profitable drug empires. Gasser’s son, José, would later join Suárez in this billion-dollar enterprise, as would Hugo Banzer’s cousin, Guillermo Banzer Ojopi, two of Bolivia’s top generals, the head of the customs office at Santa Cruz and Klaus Barbie.

Suárez’s drug syndicate became known as La Mafia Cruzeña. He enjoyed a near monopoly on the most productive coca-growing fields in the world: 80 percent of the world’s cocaine originated from his fields in the Alto Beni. He was the primary supplier of raw coca and cocaine paste to Medellín cartel. Suárez maintained one of the largest private fleets of aircraft in world, which he used to fly much of his coca paste to Colombian cocaine labs. The cocaine planes were launched from one of Suárez’s network of private airstrips. Other coca paste was shipped to Colombia via Barbie’s firm, Transmaritania.

As Suárez’s operation grew into a multibillion-dollar empire, he turned to Barbie for help with his burgeoning security needs. Barbie duly assembled his band of narco-mercenaries, which the Nazi christened Los Novios de la Muerte, the fiancés of death. Their ranks included two former SS officers, a white Rhodesian terrorist, and Joachim Fiebelkorn, a neo-fascist madman from Frankfort.

Barbie assigned fifteen bodyguards to follow Suárez’s every footstep. He ensured that Colombian buyers made their payments and sent armed bands of Novios on forays into the jungle to destroy the operations of rival drug lords. The weapons for Barbie’s men were provided gratis by the Banzer government, which in turn had bought them from Barbie’s arms company.

By the mid-1970s the Bolivian economy was in ruins. Banzer, following the advice of his close friend from Santa Cruz, Roberto Suárez, concocted a bold plan to save Bolivia: he ordered the nation’s ailing cotton fields to be planted with coca trees. Between 1974 and 1980 land in coca production tripled, prompting one DEA agent to note, “Someone out there planted a heck of a lot of trees.” This tremendous upsurge in supply sharply drove down the price of cocaine, fueling a huge new market and the rise of the Colombian cartels. The street price of cocaine in 1975 was $1,500 per gram. By 1986 the price had fallen to about $200 per gram.

“The Bolivian military leaders began to export cocaine and cocaine base as though it were a legal product, without any pretense of narcotics control,” recounted former DEA agent Michael Levine. “At the same time there was a tremendous upswing in demand from the United States. The Bolivian dictatorship quickly became the primary source of supply for the Colombian cartels, which formed during this period. And the cartels, in turn, became the main distributors of cocaine throughout the US. It was truly the beginning of the cocaine explosion of the 1980s.”

Banzer’s take from the drug trade reportedly tallied at several million dollars a year. It was an enterprise he shared with his family and friends. By 1978, Banzer’s private secretary, his son-in-law, his nephew and his wife had been arrested for cocaine trafficking in the US and Canada. Embarrassed by these revelations, Banzer stood down in 1978 and promised free elections in 1979. Despite widespread fraud and voter intimidation, the right-wing parties unexpectedly lost the elections, an event that prompted the infamous cocaine coup of 1980.

This time, the coup plotters were led by General Luis Arce Gómez, Roberto Suárez’s cousin, and his partner General Luis García-Meza. Arce Gómez, then head of Bolivia’s military intelligence agency, had been using the military to assist Suárez’s drug running since early 1970s. In plotting the coup, Arce Gómez called on the services of his close friend, the man he called “my teacher,” Klaus Barbie. The CIA was posted on the events leading up to the coup and, in fact, had been given a tape recording of a planning session involving Arce Gómez, Roberto Suárez and Klaus Barbie.

To aid the cause, Barbie recruited the help of the Italian terrorist Stefano “Alfa” Delle Chiaie. At the time, Delle Chiaie was on the move, following the murder in Washington, D.C. of the Chilean Orlando Letelier by the Italian’s associate Michael Townley, the American agent in the employ of Pinochet’s secret police. Delle Chiaie brought with him to Bolivia a group of 200 Argentine terrorists, veterans of the “dirty war.” In a nod to William Colby’s Vietnam assassins, Delle Chiaie called his band of murderers “the Phoenix Commandos.”

Klaus Barbie’s identity card for the Bolivian secret police.

Delle Chiaie had his own ties to the CIA that stretched back to the close of World War II. The young Italian, who battled his way up through street gangs in Rome and Naples, became the protégé of Count Junio Valerio Borghese, the Italian fascist known as the Black Prince. Borghese headed up Mussolini’s intelligence apparatus and hunted down and killed thousands of Italian resistance fighters. At the close of the war, Borghese was captured by Italian Communists, who were intent on seeing the butcher put to death for his crimes. But when the CIA’s legendary James Jesus Angleton, then with the OSS, learned of the Black Prince’s impending fate, he rushed to Milan and saved Borghese from the firing squad. The Black Prince spent a few months in in prison and then went to work in the CIA’s campaign to suppress the Italian left.

Delle Chiaie was recruited from his street gang into the neo-fascist group the P-2, where he intimidated Italian Communists, initiated a string of bombings and, in 1969, plotted a coup against the Italian government. When that coup failed, Delle Chiaie and Borghese fled to Franco’s Spain, where they supervised covert attacks on Basque separatists. From Madrid, Delle Chiaie launched his career as an international consultant on right-wing terrorism, lending his services to Jonas Savimbi, leader of the CIA-backed UNITA forces in Angola; José Lopez Rega, architect of Argentina’s death squads; and the Chilean dictator helped to power by the CIA, Augusto Pinochet.

On July 17, 1980 the Bolivian cocaine coup unfolded. Liberal newspapers and radio stations were bombed. The universities were shut down. Barbie and Delle Chiaie’s hooded troops, armed with machine guns, swept through the streets of La Paz in ambulances. They converged on the center of resistance, the COB building, the headquarters of the Bolivian national union. Inside was Marcelo Quiroga, a labor leader recently elected to parliament, who had called a general strike. The doors were blasted down, and Los Novios de la Muerte entered, guns blazing.

Quiroga was quickly found and shot. Severely wounded, he and a dozen other leaders were taken to army headquarters, where they were beaten and treated to Barbie’s electro-shock machines. The women prisoners were raped. Quiroga’s body was found three days later on the outskirts of La Paz. He had been shot, beaten, burned and castrated.

The following day General García-Meza was sworn in as Bolivia’s new president. He duly appointed General Arce Gómez as minister of interior. Barbie was selected as the head of Bolivia’s internal security forces and Stephano Delle Chiaie was assigned the task of securing international support for the regime, which quickly came from Argentina, Chile, South Africa and El Salvador.

Over the next few weeks, thousands of opposition leaders were rounded up and herded into the large soccer stadium in La Paz. In true Argentine style, they were shot en masse, their bodies dumped in rivers and deep canyons outside the capital. The Novios de la Muerte began dressing in SS-style uniforms and were called upon by Arce Gómez and Barbie to suppress “organized delinquency.”

In a show of support for the international drug war, the new Bolivian regime quickly began a drug suppression campaign. Klaus Barbie was appointed its supervisor. The operation had three objectives: soften criticism from the US and the United Nations of Bolivia’s role in the drug trade; eliminate 140 rivals to the Suárez monopoly; and ruthlessly suppress the regime’s political opponents. Over the next year, the cocaine generals made an estimated $2 billion in the drug trade.

“Ultimately, the situation in Bolivia became so flagrant that the regime’s backers in the United States decided to pull the plug. García-Meza was forced to resign in August 1981: he left Bolivia a wealthy man after securing his country’s position as world’s leading supplier of cocaine.

Barbie and Delle Chiaie would remain in Bolivia another year and half. The Italian police and the US DEA planned a raid to capture Delle Chiaie in 1982, but he fled Bolivia after being tipped off by a CIA contact. On January 25, 1983, Klaus Barbie was arrested and later handed over to the French. He was brought back to Lyons and imprisoned at Montluc, the scene of so many of his crimes. After his arrest in Bolivia, Barbie was asked by a French journalist if he any regrets about his life. “No, personally, I have no regrets,” Barbie said. “If there were mistakes, there were mistakes. But a man has to have a line of work, no?”

But while Barbie languished in prison, the cocaine empire he helped to build flourished. Indeed, after the masterminds of the cocaine coup fled, the situation actually deteriorated. The amount of cocaine produced in Bolivia rocketed from 35,000 metric tons in 1980 to 60,000 metric tons a year by the late 1980s. Nearly all of it was marked for sale in the US. The drug accounted for 30 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. By 1987, Bolivia was racking up $3 billion a year in cocaine sales, more than six times the value of all other Bolivian exports. In 1998 estimated 70,000 Bolivian families remain dependent on the cultivation of coca, though they earn less than $1,000 a year for their arduous work. “If narcotics were to disappear overnight, we would have rampant unemployment,” commented Flavio Machicado, the former finance minister of Bolivia. “There would be protest and open violence.”

In the 1980s, the DEA and CIA went to Bolivia to train and arm the Bolivian police’s anti-drug shock troops, the Leopards. It soon turned out that many of the Leopards had begun a fruitful partnership with the coca growers and drug traffickers. A congressional review in 1985 found that “not one hectare of coca leaf has been eradicated since the US established the narcotics assistance program in 1971.” But the CIA didn’t mind much, because the Leopards turned their guns on Indian insurgents.”

The level of official corruption also hardly abated after the exile of Barbie, Arce Gómez and García-Meza. A 1988 report by the GAO described “an unprecedented level of corruption which extends to virtually every level of Bolivian govt. and Bolivian society.” Cocaine lord Roberto Suárez himself announced in 1989 that “since the 1985 elections, all the country’s politicians have been involved in cocaine.” This point was driven home in 1997 when Suárez’s old partner Hugo Banzer once again assumed power as president of Bolivia.

As we have already noted, the career of Klaus Barbie – perhaps more strikingly than any other – illuminates the monstrosities of CIA conduct, and the drug empires it has helped spawn and protect. Such conduct, it should again be emphasized, springs not from a “rogue” Agency. but always as the expression of US government policy.

Notes.

This essay originated with a series of reports I wrote for the print edition of CounterPunch and several other now-extinct Northwest Zines: Ilium’s Burning (the Gehlen network) and Pseudotsuga (Operation Paperclip) on US intelligence agencies’ recruitment and use of Nazi war criminals after World War II. It later appeared in edited form in Whiteout: the CIA, Drugs and the Press.

Many of the documents relating to Klaus Barbie’s relationship to American intelligence agencies come from Allan Ryan’s thick report for the US Justice Department. Even so, Ryan’s conclusions are a tremendous whitewash. Incredibly, Ryan claims Barbie was the only wanted Nazi war criminal the US intelligence agencies helped to escape Europe, and he asserts that the US had no contact with Barbie after he arrived in South America. Both claims are ludicrous. Three books on Barbie’s career as a Nazi and US intelligence recruit were indispensable: Tom Bower’s Klaus Barbie, Magnus Linklater and Neal Ascherson’s The Nazi Legacy and Erhard Dabringhaus’s (one of Barbie’s US intelligence handlers) Klaus Barbie. Marcel Ophuls’s epic documentary film Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie was also an important source. The Bolivian cocaine trade is graphically detailed in Paul Eddy’s book Cocaine Wars. Michael Levine gives a gripping account of the 1980 “cocaine coup” in his book, The Big White Lie. Drug War Politics by Eve Bertram, et al. is the best account we’ve come across of the failures of the US drug policy since Reagan for Latin American countries and in the United States itself.

Aarons, Mark, and John Loftus. Unholy Trinity. St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Agee, Philip. Inside the Company: CIA Diary. Stonehill, 1975.

Agee, Philip, and Louis Wolf, eds. Dirty Work: The CIA in Western Europe. Lyle Stuart, 1978.

Allen, Charles. Nazi War Criminals in America: Facts … Action. Charles Allen Productions, 1981.

Andreas, Peter. “Drug War Zone.” Nation, Dec. 11, 1989.

Andreas, Peter, Eve Bertram, Morris Blachman, and Kenneth Sharpe. “Dead End Drug Wars.” Foreign Policy, no. 85, 1991–1992.

Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. Grove Press, 1997.

Anderson, Scott, and Jon Lee Anderson. Inside the League. Dodd & Mead, 1986.

Ashman, Charles, and Robert J. Wagman. The Nazi Hunters. Pharos Books, 1988.

Bertram, Eve, Morris Blachman, Kenneth Sharpe and Peter Andreas. Drug War Politics: The Price of Denial. Univ. of California Press, 1996.

Bird, Kai. “Klaus Barbie: A Killer’s Career.” Covert Action Information Bulletin. Winter, 1986.

Black, George. “Delle Chiaie: From Bologna to Bolivia.” Nation, April 25, 1987.

Blum, Howard. Wanted: The Search for Nazis in America. Fawcett, 1977.

Blum, William. Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Intervention Since World War II. Common Courage, 1995.

Blumenthal, Ralph. “Canadian Says Barbie Boasted of Visiting the US.” New York Times, Feb. 28, 1983.

Bower, Tom. Klaus Barbie. Pantheon, 1984.

Brill, William. Military Intervention in Bolivia: From the MNR to Military Rule. Washington, 1967.

Burke, Melvin. “Bolivia: The Politics of Cocaine.” Current History, 90, 1991.

Christie, Stuart. Stefano delle Chiaie. Refract, 1984.

Colby, Gerard, and Charlotte Dennett. Thy Will Be Done: The Conquest of the Amazon. HarperCollins, 1995.

Corn, David. “The CIA and the Cocaine Coup.” Nation, Oct. 7, 1991.

Dabringhaus, Erhard. Klaus Barbie. Acropolis Books, 1984.

Dulles, Allen. The Craft of Intelligence. Harper and Row, 1963.

Dunkerly, James. Rebellion in the Veins: Political Struggle in Bolivia, 1952–1982. Verso, 1984.

James, Daniel, ed. The Complete Diaries of Che Guevara and Other Captured Documents. Stein and Day, 1968.

Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Vintage, 1997.

Hargreaves, Clare. Snow Fields: The War on Cocaine in the Andes. Holmes and Meier, 1992.

Healy, Kevin. “Coca, the State, and the Peasantry in Bolivia.” Journal of Inter American Studies and World Affairs, 30, 1988.

Higham, Charles. Trading with the Enemy. Delacorte, 1983.

——. American Swastika. Doubleday, 1985.

Höhne, Heinz. The Order of the Death’s Head. Ballantine, 1971.

Gott, Richard. Rural Guerillas in Latin America. Penguin, 1973.

Kahn, David. Hitler’s Spies: German Military Intelligence in World War II. Macmillan, 1978.

Klare, Michael. War Without End. Random House, 1972.

Lee, Martin A. The Beast Reawakens. Little, Brown, 1997.

Lernoux, Penny. Cry of the People: The Struggle for Human Rights in Latin America – The Catholic Church in Conflict with US Policy. Penguin, 1982.

——. “The US in Bolivia: Playing Golf While the Drugs Flow.” Nation, Feb. 13, 1989.

Levine, Michael The Big White Lie. Thunder’s Mouth, 1993.

—— Deep Cover. Delacorte Press, 1990.

Linklater, Magnus, Isabel Hinton and Neal Ascherson. The Nazi Legacy: Klaus Barbie and the Rise of International Fascism. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984.

Loftus, John. The Belarus Secret. Knopf, 1982.

Loftus, John, and Mark Aarons. The Secret War Against the Jews. St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Marchetti, Victor, and John Marks. The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, Dell, 1980.

Molloy, James and Richard Thorn, eds. Beyond the Revolution: Bolivia Since 1952. Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1971.

Murphy, Brendan. The Butcher of Lyons. Empire Books, 1983.

Posner, Gerald, and John Ware. Mengele. Dell, 1987.

Ray, Michele. “In Cold Blood: How the CIA Executed Che.” Ramparts, May 1969.

Rempel, William. “CIA’s Purchase of Smuggled Arms from North Aides Probed by Panels.” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1987.

Rodríguez, Félix, and John Weisman. Shadow Warrior. Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Ryan, Allan. Klaus Barbie and the United States Government. Government Printing Office, 1983.

——. Klaus Barbie and the United States Government: Exhibits to the Report. Government Printing Office, 1983.

St. George, Andrew. “How the US Got Che.” True, April, 1969.

Shafer, D. Michael. Deadly Paradigms: The Failure of US Counter-Insurgency Policy. Princeton University Press, 1988.

Simpson, Christopher. Blowback. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988.

——. The Splendid Blond Beast. Grove, 1993.

- Office of the Comptroller, General Accounting Office. Nazis and Axis Collaborators Were Used to Further US Anti-Communist Objectives in Europe–Some Immigrated to the United States. Government Printing Office, 1985.

——. Widespread Conspiracy to Obstruct Probes of Alleged Nazi War Criminals Not Supported by Available Evidence – Controversy May Continue. Government Printing Office, 1978.

Wiesenthal, Simon. The Murderers Among Us. McGraw-Hill, 1967.