Crazy for cryptids: The International Cryptozoology Museum blurs the line between fact and fiction

Founder Loren Coleman has been searching for Bigfoot and other legendary creatures for almost six decades

Founder Loren Coleman has been searching for Bigfoot and other legendary creatures for almost six decades

EXTRAORDINARY PLACES, ROAD CULTURE

By Alexandra Charitan

In March 1960, Loren Coleman watched a film on the Yetis of the Himalayas. When he inquired about the creature (also known as the Abominable Snowman) in school, his teachers were less than helpful. They told him to “get back to work” because “[Yetis] don’t exist.” Coleman decided to conduct his own research, and a lifelong interest in cryptozoology—the study of legendary or unknown creatures—was born.

Over the past six decades, Coleman has written letters, articles, and books about cryptozoology, he has taught at universities around New England, and has conducted investigations in 48 states. As he searched for cryptids (alleged animals such as lake monsters, hairy bipeds, or swamp creatures), Coleman collected more than 10,000 objects.

A Bigfoot photo-op. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The museum’s entrance. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

“People would give me, donate, or sell me cryptozoology items from the beginning and my home became a museum of sorts,” Coleman says. The first item was a flag from Sir Edmund Hillary’s 1960 expedition to collect evidence of the Yeti. In 2009, Coleman’s collection of native art, foot casts, hair samples, models, and other memorabilia opened to the public as the International Cryptozoology Museum (ICM)—the first of its kind in the world.

ICM is located in a strip of shops and restaurants on Thompson’s Point along the banks of the Fore River in Portland, Maine. To reach the entrance of the small museum, I have to walk through a restaurant, Locally Sauced, which serves burritos, nachos, and pulled pork sandwiches.

A revitalized, industrial waterfront featuring craft breweries, an outdoor concert venue, and an ice-skating rink may not seem like the most natural place to find a museum dedicated to a fringe pseudoscience, but that’s the thing with mythical creatures—they pop up where you least expect.

“People would give me, donate, or sell me cryptozoology items from the beginning and my home became a museum of sorts,” Coleman says. The first item was a flag from Sir Edmund Hillary’s 1960 expedition to collect evidence of the Yeti. In 2009, Coleman’s collection of native art, foot casts, hair samples, models, and other memorabilia opened to the public as the International Cryptozoology Museum (ICM)—the first of its kind in the world.

ICM is located in a strip of shops and restaurants on Thompson’s Point along the banks of the Fore River in Portland, Maine. To reach the entrance of the small museum, I have to walk through a restaurant, Locally Sauced, which serves burritos, nachos, and pulled pork sandwiches.

A revitalized, industrial waterfront featuring craft breweries, an outdoor concert venue, and an ice-skating rink may not seem like the most natural place to find a museum dedicated to a fringe pseudoscience, but that’s the thing with mythical creatures—they pop up where you least expect.

To get to the museum, visitors walk through a restaurant. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Bigfoot and the Dover Demon

Probably the best-known cryptid in North America is Bigfoot (also known as Sasquatch), and he has an appropriately-big presence at the ICM. I encounter at least three versions of the upright, ape-like creature before I even pay my admission. A carved, wooden totem-style statue sits outside of the museum, and wooden cutouts line the otherwise-sterile hallway that connects ICM to Locally Sauced.

The museum includes several “Bigfoot Parking Only” signs, casts of the creature’s namesake big feet, and numerous dolls and other artwork devoted to Bigfoot. The infamous 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film plays on a loop, and visitors are encouraged to take a selfie with an eight-foot-tall replica. Although Bigfoot is traditionally associated with the Pacific Northwest, a sign urging people to “visit Squatchachusetts” proves that all over the country, people want to believe.

Bigfoot and the Dover Demon

Probably the best-known cryptid in North America is Bigfoot (also known as Sasquatch), and he has an appropriately-big presence at the ICM. I encounter at least three versions of the upright, ape-like creature before I even pay my admission. A carved, wooden totem-style statue sits outside of the museum, and wooden cutouts line the otherwise-sterile hallway that connects ICM to Locally Sauced.

The museum includes several “Bigfoot Parking Only” signs, casts of the creature’s namesake big feet, and numerous dolls and other artwork devoted to Bigfoot. The infamous 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film plays on a loop, and visitors are encouraged to take a selfie with an eight-foot-tall replica. Although Bigfoot is traditionally associated with the Pacific Northwest, a sign urging people to “visit Squatchachusetts” proves that all over the country, people want to believe.

Posters in the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Fact is fiction

ICM is billed as “the world’s only cryptozoology museum,” but that’s no longer true. In fact, “truth” is a loose concept within the confines of a museum dedicated to cryptids, the very existence of which haven’t yet been verified by traditional science. A lot of the “evidence” presented in the museum may seem suspect, but the roots of cryptozoology are planted firmly within the realm of provable science.

“Hidden animals with which cryptozoology is concerned, are by definition very incompletely known,” Bernard Heuvelmans wrote in the 1988 journal Cryptozoology. ”To gain more credence, they have to be documented as carefully and exhaustively as possible by a search through the most diverse fields of knowledge. Cryptozoological research thus requires not only a thorough grasp of most of the zoological sciences, including, of course, physical anthropology, but also a certain training in such extraneous branches of knowledge as mythology, linguistics, archaeology, and history.”

BY MOLLY MCBRIDE JACOBSON FEBRUARY 24, 2017

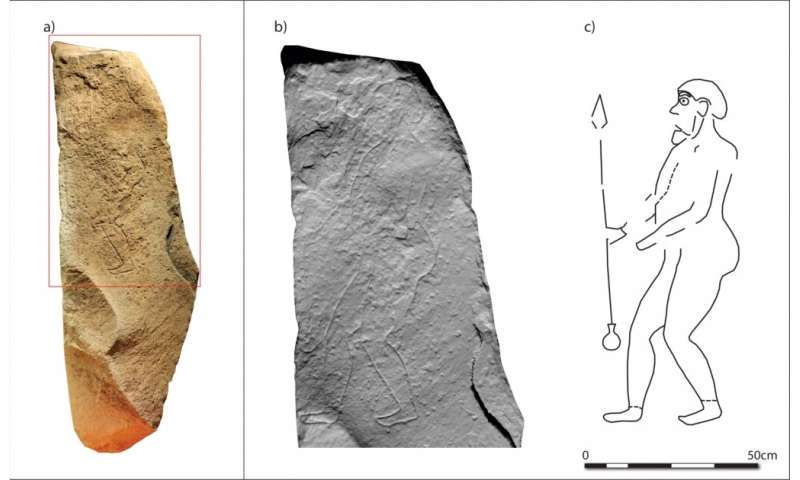

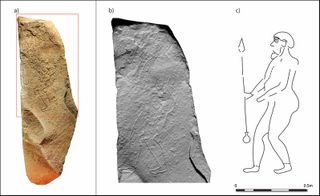

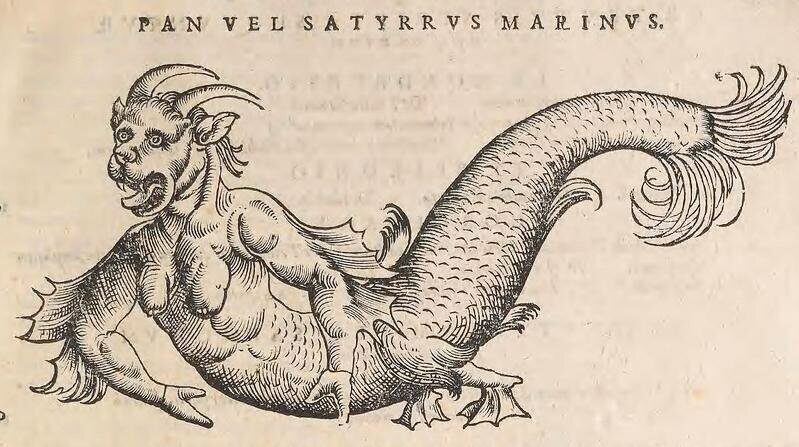

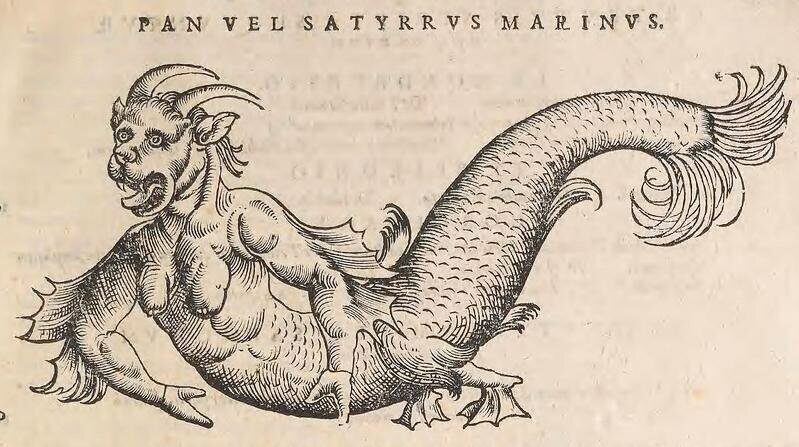

A "sea devil" from Icones animalium (1553). CONRAD GESSNER/PUBLIC DOMAIN

In This Story

PLACE

Mothman Statue

PLACE

Piasa Bird

PLACE

Pope Lick Trestle Bridge

A CRYPTID IS A CREATURE whose existence, diplomatically put, cannot be proved or disproved by science. Cryptid lore tends to be less fantastical than ghost stories or fairytales, but not altogether believable. For some though, an unusual rock, unexplained crop circles, a footprint, or some hair are all the evidence they need that there are creatures unknown to humanity, hiding in the woods.

In these places, tales of mysterious creatures have become so embroiled within local narrative that whether the beast actually exists or not doesn’t matter anymore. Can you imagine Loch Ness without its monster?

HAIRY HUMANOIDS

The Sasquatch, or as it’s colloquially known, Bigfoot, is America’s best known cryptid. It is typically depicted as a giant ape, standing around seven feet tall. Sasquatch lore extends back to American Indian mythology, which describes hairy wild men living in the woods. Anomalous sightings continued into the 20th century, but Sasquatch mania reached its peak following the famed Patterson-Gimlin tape.

Bigfoot is generally associated with the Pacific Northwest, with most sightings reported in Washington. Ape Canyon was the site in which a group of miners came under attack by a gang of wild “apemen” in 1924. According to the five miners, all of whom survived the incident and seemed convinced of its facts, they were asleep in their cabin when the assault started, and the beasts seemed out for blood. The event was widely publicized and no logical explanation was ever found.

Ape Canyon: Sasquatch Country

COUGAR, WASHINGTON

That said, not all sea monsters take the form of slithering water snakes. The Kelpies of Scottish lore are massive demonic horses found in rivers and streams.

The Kelpies

GRANGEMOUTH, SCOTLAND

Tenshou-Kyousha Shrine Mermaid Mummy

FUJINOMIYA, JAPAN

The Hull Mermaid

HULL, ENGLAND

Feejee Mermaid at the Nature Museum

GRAFTON, VERMONT

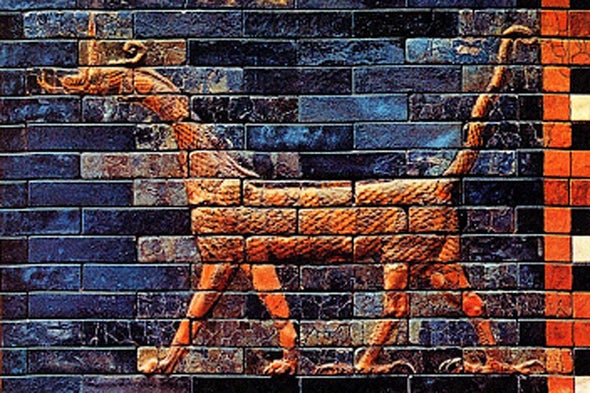

CHIMERAS

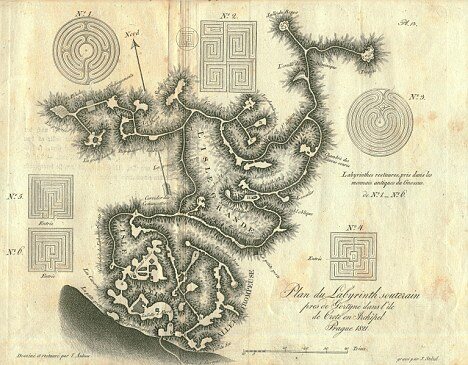

The chimera, another creature of Greek mythology, was said to have the body of a lion, the head of a goat, and a snake for a tail, though today the term is applied to any creature with the body parts of various animals. Nobody does body horror like the Ancient Greeks, whose Minotaur myth (the half-man, half-bull trapped as the protector of the labyrinth) persists to this day.

Labyrinthos Caves: the Minotaur’s Home

GREECE

A cast of Bigfoot’s big foot. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

It’s hard to pick favorites, but Coleman has a soft spot for a creature closer to home: the Dover Demon. The small, orange, hairless being was reported by four different people over the course of one week, in Dover, Massachusetts in 1977. It was spotted both sitting on a wall and leaning against a tree. Eyewitnesses described it as having large, glowing eyes and tendril-like fingers. Although skeptics have dismissed the Dover Demon as a foal or a moose calf, “the whole idea of cryptozoology is to be open-minded about the possible discovery of new animals or species,” Coleman says.

While some people are quick to dismiss cryptozoology as a silly pseudoscience, Coleman urges people to not only open their minds, but their eyes and ears as well. Most cryptids had been appearing in folklore and local legends for thousands of years before Coleman brought them to Portland. “Listening to Indigenous people is key,” he says. “Ethno-known information is important, and then you can look for physical evidence.”

It’s hard to pick favorites, but Coleman has a soft spot for a creature closer to home: the Dover Demon. The small, orange, hairless being was reported by four different people over the course of one week, in Dover, Massachusetts in 1977. It was spotted both sitting on a wall and leaning against a tree. Eyewitnesses described it as having large, glowing eyes and tendril-like fingers. Although skeptics have dismissed the Dover Demon as a foal or a moose calf, “the whole idea of cryptozoology is to be open-minded about the possible discovery of new animals or species,” Coleman says.

While some people are quick to dismiss cryptozoology as a silly pseudoscience, Coleman urges people to not only open their minds, but their eyes and ears as well. Most cryptids had been appearing in folklore and local legends for thousands of years before Coleman brought them to Portland. “Listening to Indigenous people is key,” he says. “Ethno-known information is important, and then you can look for physical evidence.”

Loren Coleman, founder of the International Cryptozoology Museum. | Photo courtesy of Loren Coleman.

Fact is fiction

ICM is billed as “the world’s only cryptozoology museum,” but that’s no longer true. In fact, “truth” is a loose concept within the confines of a museum dedicated to cryptids, the very existence of which haven’t yet been verified by traditional science. A lot of the “evidence” presented in the museum may seem suspect, but the roots of cryptozoology are planted firmly within the realm of provable science.

“Hidden animals with which cryptozoology is concerned, are by definition very incompletely known,” Bernard Heuvelmans wrote in the 1988 journal Cryptozoology. ”To gain more credence, they have to be documented as carefully and exhaustively as possible by a search through the most diverse fields of knowledge. Cryptozoological research thus requires not only a thorough grasp of most of the zoological sciences, including, of course, physical anthropology, but also a certain training in such extraneous branches of knowledge as mythology, linguistics, archaeology, and history.”

A handpainted banner. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A mythical beast. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

You can’t break the rules without first learning what they are, and according to ICM’s website, “cryptozoology is a ‘gateway science’ for many young people’s future interest in biology, zoology, wildlife studies, paleoanthropology, paleontology, anthropology, ecology, marine sciences, and conservation.” As such, the museum also features exhibits on creatures that were once thought to be too fantastical to be real or long since extinct—until actual, live specimens were discovered.

In 1938, fishermen off the coast of Africa discovered a coelacanth, a fish that was thought to have become extinct around 66 million years ago. Between 1938 and 1975, 84 more specimens were caught and recorded, and Coleman’s collection includes the only life-size model of the rediscovered fish displayed in North America. The two-floor museum also includes alleged Yeti hair samples and a FeeJee Mermaid—half monkey, half fish—created for a film about P. T. Barnum, who notoriously loved a hoax.

I want to believe

I have a feeling that P.T. Barnum would have loved ICM—the longer I browse the exhibits, the harder it becomes to distinguish fact from fiction. Since actual artifacts are understandably hard to come by, the museum has several full-sized art sculptures including a Tatzelwurm (a mythical, cat-headed serpent) and a lifesize thylacine (a real-life dog-kangaroo hybrid that is now thought to be extinct).

You can’t break the rules without first learning what they are, and according to ICM’s website, “cryptozoology is a ‘gateway science’ for many young people’s future interest in biology, zoology, wildlife studies, paleoanthropology, paleontology, anthropology, ecology, marine sciences, and conservation.” As such, the museum also features exhibits on creatures that were once thought to be too fantastical to be real or long since extinct—until actual, live specimens were discovered.

In 1938, fishermen off the coast of Africa discovered a coelacanth, a fish that was thought to have become extinct around 66 million years ago. Between 1938 and 1975, 84 more specimens were caught and recorded, and Coleman’s collection includes the only life-size model of the rediscovered fish displayed in North America. The two-floor museum also includes alleged Yeti hair samples and a FeeJee Mermaid—half monkey, half fish—created for a film about P. T. Barnum, who notoriously loved a hoax.

I want to believe

I have a feeling that P.T. Barnum would have loved ICM—the longer I browse the exhibits, the harder it becomes to distinguish fact from fiction. Since actual artifacts are understandably hard to come by, the museum has several full-sized art sculptures including a Tatzelwurm (a mythical, cat-headed serpent) and a lifesize thylacine (a real-life dog-kangaroo hybrid that is now thought to be extinct).

A mermaid creature. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

One of many Bigfoot depictions. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

I try to keep an open mind, but after a few hours spent browsing Coleman’s collection, I wouldn’t exactly consider myself a cryptozoology convert. However, everything known was once unknown, which seems to also suggest the opposite: With enough time and evidence, anything unknown can presumably become known.

“Cryptozoology is all about patience and passion—and so is the museum,” Coleman says. “People enjoy themselves if they come visit to allow new ideas in. The museum teaches critical thinking but also open-mindedness.”Previous

I try to keep an open mind, but after a few hours spent browsing Coleman’s collection, I wouldn’t exactly consider myself a cryptozoology convert. However, everything known was once unknown, which seems to also suggest the opposite: With enough time and evidence, anything unknown can presumably become known.

“Cryptozoology is all about patience and passion—and so is the museum,” Coleman says. “People enjoy themselves if they come visit to allow new ideas in. The museum teaches critical thinking but also open-mindedness.”Previous

The elusive Fur Bearing Trout. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Another depiction of Bigfoot. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Bigfoot signs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A collection of skulls. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Bigfoot or giant ape? | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Footprint casts. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Various examples of scat. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Cryptozoology-inspired labels. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A Fiji Mermaid. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

SUCH CREATURES WERE POPULAR IN FOLKLORE MUSEUMS,

WHEN I WAS A KID WE WOULD GO ANNUALLY THROUGH BANFF ON VACATION

AND I ALWAYS STOPPED AT THE FOLKLORE MUSEUM THERE WHERE SUCH A

HALF CHIMP HALF TROUT MERMAN/MERMAID WAS ON DISPLAY

HOWEVER THE REAL THRILL WAS THE 12 FT KODIAK BEAR, LUCKILY STUFFED.

SEE BELOW

SEE BELOW

Swamp creature memorabilia. | Photo: Alexandra CharitanNext

From Labor Day until Memorial Day, the International Cryptozoology Museum is open Mondays, Wednesdays, and Sundays, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 6 pm. It is closed on Tuesdays.

Where to Find the World's Best Hometown Monsters

Where to Find the World’s Best Hometown Monsters

Here are 25 places to see yetis, sea monsters, Sasquatch, and other cryptids.

From Labor Day until Memorial Day, the International Cryptozoology Museum is open Mondays, Wednesdays, and Sundays, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 6 pm. It is closed on Tuesdays.

Where to Find the World's Best Hometown Monsters

Where to Find the World’s Best Hometown Monsters

Here are 25 places to see yetis, sea monsters, Sasquatch, and other cryptids.

BY MOLLY MCBRIDE JACOBSON FEBRUARY 24, 2017

A "sea devil" from Icones animalium (1553). CONRAD GESSNER/PUBLIC DOMAIN

In This Story

PLACE

Mothman Statue

PLACE

Piasa Bird

PLACE

Pope Lick Trestle Bridge

A CRYPTID IS A CREATURE whose existence, diplomatically put, cannot be proved or disproved by science. Cryptid lore tends to be less fantastical than ghost stories or fairytales, but not altogether believable. For some though, an unusual rock, unexplained crop circles, a footprint, or some hair are all the evidence they need that there are creatures unknown to humanity, hiding in the woods.

In these places, tales of mysterious creatures have become so embroiled within local narrative that whether the beast actually exists or not doesn’t matter anymore. Can you imagine Loch Ness without its monster?

HAIRY HUMANOIDS

The Sasquatch, or as it’s colloquially known, Bigfoot, is America’s best known cryptid. It is typically depicted as a giant ape, standing around seven feet tall. Sasquatch lore extends back to American Indian mythology, which describes hairy wild men living in the woods. Anomalous sightings continued into the 20th century, but Sasquatch mania reached its peak following the famed Patterson-Gimlin tape.

Bigfoot is generally associated with the Pacific Northwest, with most sightings reported in Washington. Ape Canyon was the site in which a group of miners came under attack by a gang of wild “apemen” in 1924. According to the five miners, all of whom survived the incident and seemed convinced of its facts, they were asleep in their cabin when the assault started, and the beasts seemed out for blood. The event was widely publicized and no logical explanation was ever found.

Ape Canyon: Sasquatch Country

COUGAR, WASHINGTON

Ape Canyon, where the miners were attacked by “apemen.” JORDAN/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Sasquatch mythos has caught many in its spell. Refusing to accept claims that Bigfoot sightings are actually black bears or intentional hoaxes, believers continue their search for the hidden primate. California, Oregon, Washington and Canada are dotted with Sasquatch museums and research institutions for those who want to see footprints, photos, and other evidence.

Bigfoot Discovery Museum

FELTON, CALIFORNIA

The Sasquatch mythos has caught many in its spell. Refusing to accept claims that Bigfoot sightings are actually black bears or intentional hoaxes, believers continue their search for the hidden primate. California, Oregon, Washington and Canada are dotted with Sasquatch museums and research institutions for those who want to see footprints, photos, and other evidence.

Bigfoot Discovery Museum

FELTON, CALIFORNIA

Bigfoot Discovery Museum in Felton. INFIDELIC/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

China Flat Museum Bigfoot Collection

WILLOW CREEK, CALIFORNIA

China Flat Museum Bigfoot Collection

WILLOW CREEK, CALIFORNIA

Bigfoot Museum artifacts. ATLAS OBSCURA USER LADYLAURADEMAREST

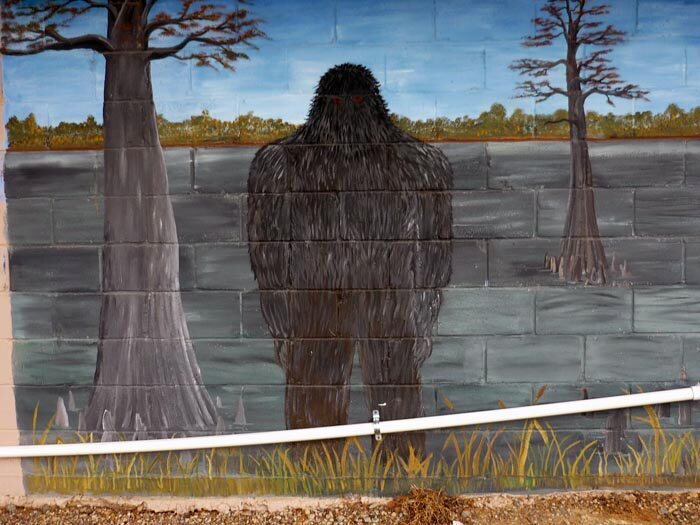

Bipedal hairy beasts aren’t confined to the West Coast though. Illinois and Ohio have remarkably high rates of Bigfoot sightings, and Arkansas has its own permutation: the Boggy Creek monster.

The Boggy Creek Monster

FOUKE, ARKANSAS

Bipedal hairy beasts aren’t confined to the West Coast though. Illinois and Ohio have remarkably high rates of Bigfoot sightings, and Arkansas has its own permutation: the Boggy Creek monster.

The Boggy Creek Monster

FOUKE, ARKANSAS

A Boggy Creek monster mural. ATLAS OBSCURA USER NICHOLAS JACKSON

Florida has its own version of Bigfoot too. Its presence is announced by the foul odor that earned it its nickname: the Skunk Ape.

Skunk Ape Research Headquarters

OCHOPEE, FLORIDA

Florida has its own version of Bigfoot too. Its presence is announced by the foul odor that earned it its nickname: the Skunk Ape.

Skunk Ape Research Headquarters

OCHOPEE, FLORIDA

A sign directs visitors to “SKUNK APE TERRITORY.” JOHN MOSBAUGH/CC BY 2.0

SEA MONSTERS

Ever since sailors first traversed the ocean they have returned with stories of unbelievable creatures emerging from the murky depths. Perhaps it’s because we didn’t (and still don’t) really know what lies beneath the ocean’s surface, a whale or squid could be mistaken for the Leviathan or a Kraken.

That lore is celebrated in places like Skrímslasetrið, Iceland’s sea monster museum. Maritime history is inextricable from Icelandic identity, which includes many tales of ocean beasts lurking just off the edge of the map.

Skrímslasetrið

ICELAND

SEA MONSTERS

Ever since sailors first traversed the ocean they have returned with stories of unbelievable creatures emerging from the murky depths. Perhaps it’s because we didn’t (and still don’t) really know what lies beneath the ocean’s surface, a whale or squid could be mistaken for the Leviathan or a Kraken.

That lore is celebrated in places like Skrímslasetrið, Iceland’s sea monster museum. Maritime history is inextricable from Icelandic identity, which includes many tales of ocean beasts lurking just off the edge of the map.

Skrímslasetrið

ICELAND

1590 map of Iceland with sea monsters, all of which are detailed at Iceland’s sea monster museum. AUSTRIAN NATIONAL LIBRARY/PUBLIC DOMAIN

Creature stories also provided a useful explanation for misunderstood natural phenomena. The geyser of Kauai’s Spouting Horn blowhole was originally attributed to a giant lizard monster trapped beneath the rock.

Spouting Horn Blowhole

KOLOA, HAWAII

Creature stories also provided a useful explanation for misunderstood natural phenomena. The geyser of Kauai’s Spouting Horn blowhole was originally attributed to a giant lizard monster trapped beneath the rock.

Spouting Horn Blowhole

KOLOA, HAWAII

Spouting Horn Park. GARDEN STATE HIKER/CC BY 2.0

Lakes have their fair share of mystery too. The Loch Ness Monster is the most widely known, but prehistoric serpentine beasts have been reported on almost every continent.

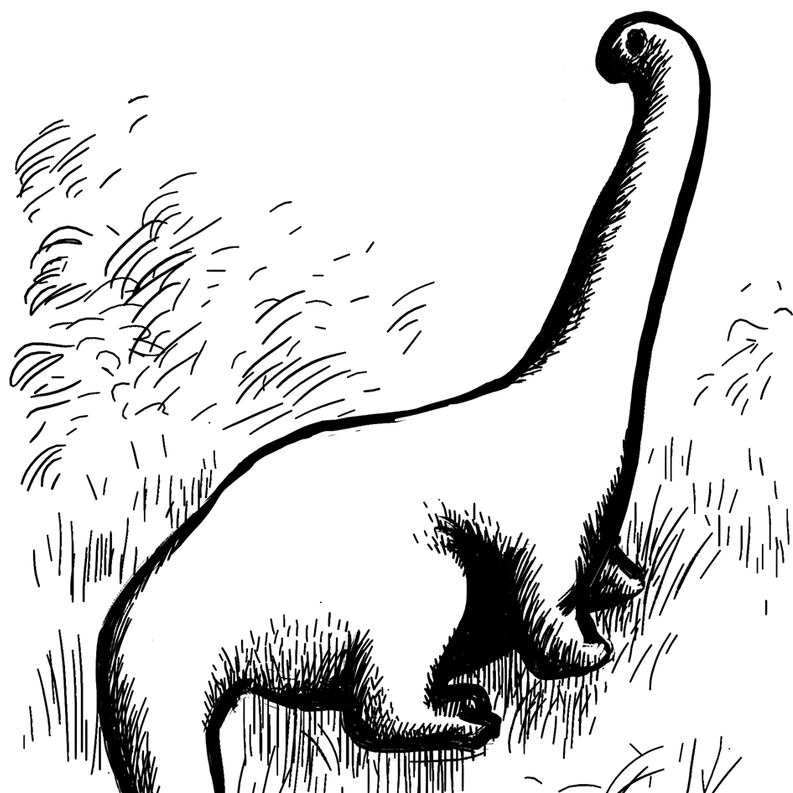

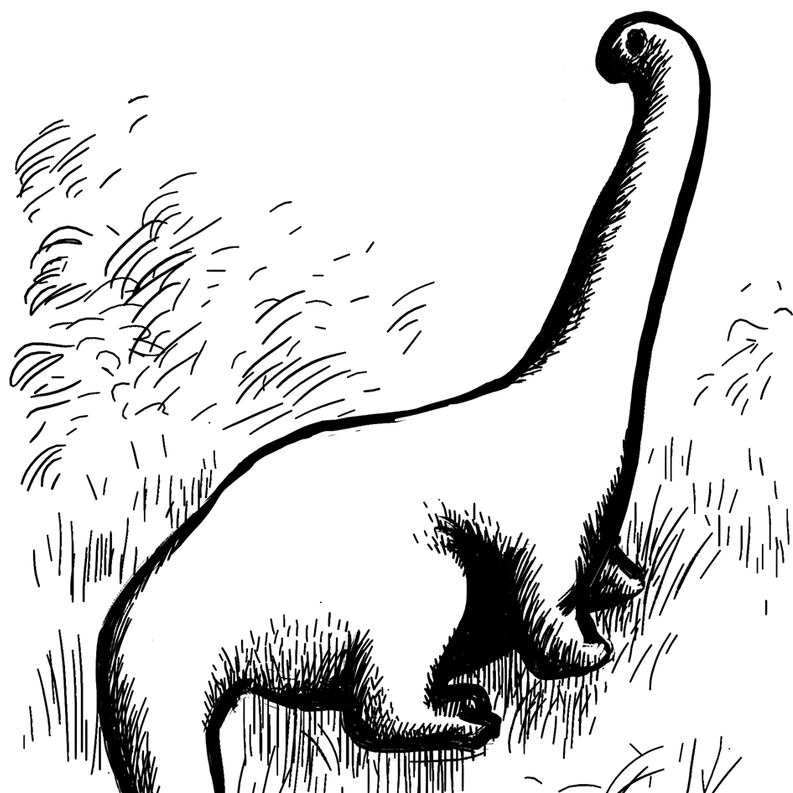

Lake Tele: Home of the Legendary Mokèlé-mbèmbé Monster

EPENA, REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Lakes have their fair share of mystery too. The Loch Ness Monster is the most widely known, but prehistoric serpentine beasts have been reported on almost every continent.

Lake Tele: Home of the Legendary Mokèlé-mbèmbé Monster

EPENA, REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

A sketch of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé. JEAN-NO/FAL 1.3

That said, not all sea monsters take the form of slithering water snakes. The Kelpies of Scottish lore are massive demonic horses found in rivers and streams.

The Kelpies

GRANGEMOUTH, SCOTLAND

MERMAIDS

Mermaids are another sea beast, albeit a significantly more alluring version. Much of our modern mythos surrounding mermaids comes from Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid, but before the 19th century, mermaids were thought of as the deceptive, even evil sprites, no doubt based on the sirens in Homer’s Odyssey.

Mermaids are another sea beast, albeit a significantly more alluring version. Much of our modern mythos surrounding mermaids comes from Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid, but before the 19th century, mermaids were thought of as the deceptive, even evil sprites, no doubt based on the sirens in Homer’s Odyssey.

Doxey Pool, where a mermaid named Jenny Greenteeth is said to seduce and drown young men. MICHAEL ELY/CC BY-SA 2.0

The myth of Feejee mermaids was transported to the West from Japan. Travelers saw mummified “mermaids” in shrines like the 1,400-year-old one at the Tenshou-Kyousha Shrine. Allegedly, this mermaid was once a fisherman who trespassed in protected waters and was transformed into a hideous creature as punishment.

The myth of Feejee mermaids was transported to the West from Japan. Travelers saw mummified “mermaids” in shrines like the 1,400-year-old one at the Tenshou-Kyousha Shrine. Allegedly, this mermaid was once a fisherman who trespassed in protected waters and was transformed into a hideous creature as punishment.

Tenshou-Kyousha Shrine Mermaid Mummy

FUJINOMIYA, JAPAN

The ancient mermaid mummy. ATLAS OBSCURA USER JUSTIN ARNOLD

These weird hybrids, crafted from the upper half of a monkey and the bottom half of a fish, may have been inspired by the Japanese kappa, a mischievous water spirit.

Despite the fact that they were nothing like the lovely fishtailed maidens of fairytales, Feejee mermaids (as they came to be called—allegedly brought back from Fiji, not Japan) captured the Western imagination. They were quickly disproved as fakes, yet after P.T. Barnum had one in his famous sideshow, no cabinet of curiosity was complete without one.

These weird hybrids, crafted from the upper half of a monkey and the bottom half of a fish, may have been inspired by the Japanese kappa, a mischievous water spirit.

Despite the fact that they were nothing like the lovely fishtailed maidens of fairytales, Feejee mermaids (as they came to be called—allegedly brought back from Fiji, not Japan) captured the Western imagination. They were quickly disproved as fakes, yet after P.T. Barnum had one in his famous sideshow, no cabinet of curiosity was complete without one.

WHEN I WAS A KID WE WOULD GO ANNUALLY THROUGH BANFF ON VACATION

AND I ALWAYS STOPPED AT THE FOLKLORE MUSEUM THERE WHERE SUCH A

HALF CHIMP HALF TROUT MERMAN/MERMAID WAS ON DISPLAY

HOWEVER THE REAL THRILL WAS THE 12 FT KODIAK BEAR, LUCKILY STUFFED.

The Banff Mermaid

BANFF, ALBERTA The Banff mermaid, one of the most famous Feejee mermaids. BANFF LAKE LOUISE/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Banff mermaid, one of the most famous Feejee mermaids. BANFF LAKE LOUISE/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

BANFF, ALBERTA

The Banff mermaid, one of the most famous Feejee mermaids. BANFF LAKE LOUISE/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Banff mermaid, one of the most famous Feejee mermaids. BANFF LAKE LOUISE/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0The Hull Mermaid

HULL, ENGLAND

Feejee Mermaid at the Nature Museum

GRAFTON, VERMONT

CHIMERAS

The chimera, another creature of Greek mythology, was said to have the body of a lion, the head of a goat, and a snake for a tail, though today the term is applied to any creature with the body parts of various animals. Nobody does body horror like the Ancient Greeks, whose Minotaur myth (the half-man, half-bull trapped as the protector of the labyrinth) persists to this day.

Labyrinthos Caves: the Minotaur’s Home

GREECE

A map drawn in 1812 depicts the network of tunnels and caves forming the labyrinth. FRANZ WILHELM SIEBER/PUBLIC DOMAIN

Chimera made their way into American folklore. The Texas Woofus in Dallas is a longhorned pig-legged sheep-bird. Its critics call it pagan, and they may not be so far off the mark.

The Texas Woofus

DALLAS, TEXAS

Chimera made their way into American folklore. The Texas Woofus in Dallas is a longhorned pig-legged sheep-bird. Its critics call it pagan, and they may not be so far off the mark.

The Texas Woofus

DALLAS, TEXAS

Re-creation of the Texas Woofus in Fair Park in Dallas. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/LC-DIG-HIGHSM- 29146 (ONLINE) [P&P]

Another American chimera is the Piasa bird, a mysterious feathered beast painted on a rock in Alton, Illinois. The painting has been there since at least the 1670s, though no one knows its origin.

Another American chimera is the Piasa bird, a mysterious feathered beast painted on a rock in Alton, Illinois. The painting has been there since at least the 1670s, though no one knows its origin.

The elusive Piasa Bird. ATLAS OBSCURA USER MATTB

The chimera best known to Americans is the jackalope, a jackrabbit with the antlers of a buck. Mismatched animals like this abound around the world though, likely because hucksters could prove their existence through falsified taxidermy, or “gaffs.” Still, reports of bunnies with massive horns proliferate in the Southwest and elsewhere.

The chimera best known to Americans is the jackalope, a jackrabbit with the antlers of a buck. Mismatched animals like this abound around the world though, likely because hucksters could prove their existence through falsified taxidermy, or “gaffs.” Still, reports of bunnies with massive horns proliferate in the Southwest and elsewhere.

The skvader, a rabbit with the wings of a grouse. ATLAS OBSCURA USER JIBLITE

Not all cryptids and chimera are leporine and sweet though. Some are more sinister, like the Pope Lick Monster, named after the Pope Lick Trestle Bridge it has been sighted beneath. It is said to be a monstrous man-goat hybrid that lures its victims onto the railway trestle.

Not all cryptids and chimera are leporine and sweet though. Some are more sinister, like the Pope Lick Monster, named after the Pope Lick Trestle Bridge it has been sighted beneath. It is said to be a monstrous man-goat hybrid that lures its victims onto the railway trestle.

The Pope Lick Trestle Bridge, which the monster is said to live beneath. DAVID KIDD/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

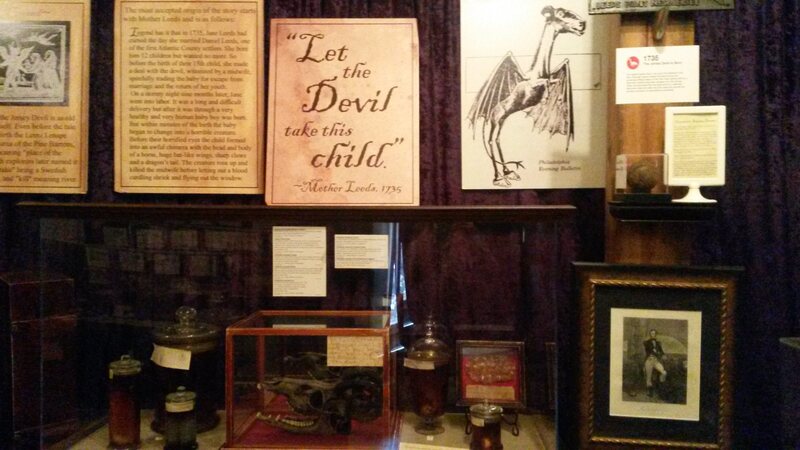

The Jersey Devil was another cryptid seen throughout New Jersey in the 19th and early 20th century. In 1909 alone, hundreds of people reported seeing an unknown creature flying over the Pine Barrens, a forested area on the Jersey coast. They described it as something like a kangaroo with hooves and leathery bat wings that would let out a terrifying shriek before disappearing from the sky. The Jersey Devil hasn’t been reported in recent years, though its memory is now thoroughly embedded in New Jersey folklore.

The Jersey Devil was another cryptid seen throughout New Jersey in the 19th and early 20th century. In 1909 alone, hundreds of people reported seeing an unknown creature flying over the Pine Barrens, a forested area on the Jersey coast. They described it as something like a kangaroo with hooves and leathery bat wings that would let out a terrifying shriek before disappearing from the sky. The Jersey Devil hasn’t been reported in recent years, though its memory is now thoroughly embedded in New Jersey folklore.

Jersey Devil artifacts at the Paranormal Museum. ATLAS OBSCURA USER JANE WEINHARDT

One of America’s more recent cryptids is the Mothman. In November of 1966, numerous people reported seeing a man-like figure with wings spanning upwards of ten feet. Those who saw the creature from their cars reported that its eyes shone red like bicycle reflectors when their headlights hit it. After a local bridge collapsed, killing dozens, Mothman sightings ceased. Conspiracies began to arise. The sightings had all been near the TNT area, a WWII munitions factory, leading some to surmise that the Mothman was a military experiment or an alien visitor.

The mystery was never solved, though skeptics claim it may have simply been an owl. Nevertheless, the story inspired a book and several films, and Point Pleasant commemorates its cryptid with a storefront museum as well as a downtown statue.

Mothman Statue

One of America’s more recent cryptids is the Mothman. In November of 1966, numerous people reported seeing a man-like figure with wings spanning upwards of ten feet. Those who saw the creature from their cars reported that its eyes shone red like bicycle reflectors when their headlights hit it. After a local bridge collapsed, killing dozens, Mothman sightings ceased. Conspiracies began to arise. The sightings had all been near the TNT area, a WWII munitions factory, leading some to surmise that the Mothman was a military experiment or an alien visitor.

The mystery was never solved, though skeptics claim it may have simply been an owl. Nevertheless, the story inspired a book and several films, and Point Pleasant commemorates its cryptid with a storefront museum as well as a downtown statue.

Mothman Statue

he Mothman Statue in Point Pleasant. OZINOH/CC BY-NC 2.0

Cryptids come from all kinds of sources—misunderstandings of natural phenomena, tall tales, and sometimes, sheer human ingenuity, as with Karachi’s very strange fortune-telling fox woman, Mumtaz Begum. They can become a mascot for the place that claims them, a weird source of pride for the people that live there.

Is there a cryptid lurking in your hometown we should know about? Have your own Feejee mermaid or creepy chimera? Add it to the Atlas!

ATLAS OBSCURA TRIPS

Cryptids come from all kinds of sources—misunderstandings of natural phenomena, tall tales, and sometimes, sheer human ingenuity, as with Karachi’s very strange fortune-telling fox woman, Mumtaz Begum. They can become a mascot for the place that claims them, a weird source of pride for the people that live there.

Is there a cryptid lurking in your hometown we should know about? Have your own Feejee mermaid or creepy chimera? Add it to the Atlas!

ATLAS OBSCURA TRIPS

Tetrapod Zoology

Tetrapod Zoology

Cropped version of the O'Connor Loch Ness monster photo - note how the far left part of the image (normally cropped out!) looks weird for what's meant to be part of an animal's body. It's a good match for the corresponding part of an inverted kayak (

Cropped version of the O'Connor Loch Ness monster photo - note how the far left part of the image (normally cropped out!) looks weird for what's meant to be part of an animal's body. It's a good match for the corresponding part of an inverted kayak (