In a few months, Covid-19 has remade our political horizons entirely.

History moves slowly, then all at once. The coronavirus crisis has catapulted us into the latter rhythm. The pace of events has accelerated sharply; the course of events has become impossible to predict. In retrospect, 2020 may end up being a 1968 or a 1917: a year of leaps and ruptures, and a dividing line between one era and the next.

How might we characterize the new era? It’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions about a period that is in the earliest phases of its formation. Still, even in fast-moving moments, it’s possible to work up a preliminary sketch. For such a sketch to be useful, though, it must capture, albeit in rough strokes, the sharpness of the break and the newness of the situation produced by it. As Stuart Hall wrote:

When a conjuncture unrolls, there is no “going back.” History shifts gears. The terrain changes. You are in a new moment. You have to attend, “violently,” with all the “pessimism of the intellect” at your command, to the “discipline of the conjuncture.”

A conjuncture is a thing made out of other things—literally, a “joining together.” So a good way to start when trying to attend to it is to attend to the various elements that combine to create it. Ideally, this shouldn’t just be a laundry list of various things that are happening but also an account of how they fit together, a theory of the complex, contradictory whole that is generated by their interaction.

This is difficult work, and it requires a sustained, collective effort. It’ll take a lot of people thinking and acting together to make sense of our new terrain. What follows is an early contribution: a partial inventory of circumstances in the US and a provisional picture of how they fit together.

The economy is collapsing. Goldman Sachs economists have predicted an annualized 34 percent decline in GDP in the second quarter of 2020—an implosion with no historical precedent. By comparison, the worst annual decline on record is 13 percent, which happened in 1932 during the Great Depression. Goldman’s predictions for the rest of 2020 are somewhat rosier: a return to double-digit growth in the third and fourth quarters, so that GDP falls by 6.2 percent for the full year on an annual average basis.

These numbers may ultimately be too optimistic, however. They take for granted that lockdowns and social distancing will be relaxed enough towards the end of the year for something resembling normal life to resume. By contrast, the economists Warwick McKibbin and Roshen Fernando suggest, more plausibly, that the economic fallout from the coronavirus crisis will be worse. They estimate that a pandemic that lasts a year and kills a million people—well within the range of current CDC projections, and perhaps too low given the current pace of infection—would reduce GDP for the year by 8.4 percent.

But a precipitous drop in growth isn’t the only cause for concern. We may also be facing another financial crisis soon, which would make the situation considerably more painful. Corporate debt is particularly vulnerable, partly as a result of how governments handled the last financial crisis. To combat the 2008 meltdown, central bankers made money cheap. This in turn encouraged companies to issue bonds, largely to finance mergers and acquisitions and stock buybacks. Since most of these companies aren’t sitting on huge cash piles, even minor disruptions may make it impossible for them to service their debt. Given the immense volume of this debt—the global value of non-financial corporate bonds reached $13.5 trillion at the end of 2019—a crunch could easily sink the financial system, freezing up credit markets and leading to a wave of bankruptcies among employers.

It’s little comfort, then, that investors have been fleeing assets of all kinds in recent weeks: not just corporate bonds, but historical safe havens like gold and Treasury bonds. The Fed has acted aggressively, using tools similar to the ones it deployed in 2008: slashing interest rates and buying up various financial assets, including corporate bonds. Still, the ambivalent response of markets to these moves suggests they may not be enough. Stocks rallied in anticipation of the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill, and continued their gains after the bill passed. But there is little doubt that more upheaval lies ahead.

If the swiftness of the economic contraction inflicted by the pandemic is one feature that distinguishes our present crisis from previous ones, another is the particular segment of the economy that will suffer the most from that contraction: services. Services usually don’t take the worst hit during recessions. That’s because they can’t be stored, so they have to be consumed right away.

The coronavirus crisis may break this pattern, however. “This will probably be the world’s first recession that starts in the service sector,” the economist Gabriel Mathy told the New York Times. In a pandemic, services are uniquely vulnerable. For instance, people won’t go get their hair cut, either because they’re afraid of being infected or because a government-mandated shutdown has closed the barbershop. And because you can’t store the output of services—a barber can’t stockpile haircuts in a warehouse until demand picks up again—businesses quickly go bankrupt, and the layoffs come hard and fast.

The human toll of such layoffs will be immense, because the service sector is where most Americans work. According to the latest estimate by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 71 percent of all non-farm payroll employees—more than a hundred million people—are in the service sector. Granted, services is a heterogenous category, encompassing everything from stockbrokers to fast-food workers. But most of the growth in recent decades has been on the lower end of the wage spectrum, and this is also where most of the pain will be felt.

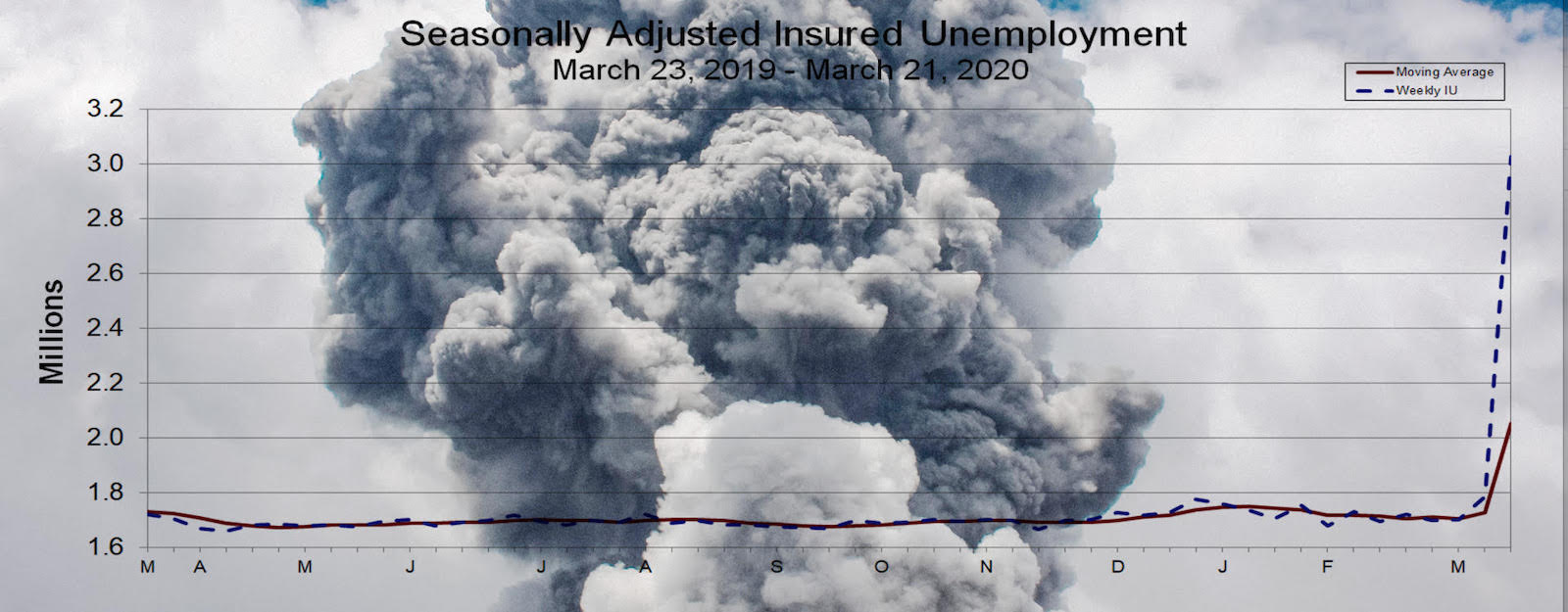

That pain is already being felt on a very large scale. In the week ending March 21, 3.3 million people applied for unemployment insurance. The following week, that number doubled to 6.6 million—nearly ten times the record set in 1982. The layoffs are concentrated in the service sector, particularly its lower-wage layers. The coming weeks will almost certainly bring more bad news. Goldman expects the unemployment rate to hit 15 percent; the St. Louis Fed says it could surge as high as 32.1 percent.

These numbers reflect the disintegration of a central pillar of the US economic model. For decades, the service sector has played an essential role in stabilizing the labor market. Because services are more difficult to automate—it’s harder to automate the production of a haircut than the production of an automobile—they have lower rates of productivity growth, which means they need more labor. This is what has enabled the service sector to absorb the workers that the manufacturing sector began shedding in the 1970s as a global crisis of overcapacity set in. Services can’t serve as the growth engine that manufacturing did, as the worsening performance of the US economy since the 1970s makes clear. But they have provided a steady supply of jobs.

The pandemic shuts off this safety valve. With the service sector in freefall, there is no longer anywhere for the surplus labor generated by decades of economic stagnation to go.

Of course, some of those who were laid off will eventually find new jobs, particularly if the post-crisis rebound follows the more optimistic estimates. But the economy they return to will have permanently changed. Small businesses, which currently employ nearly half of the country’s private-sector workforce, will be decimated. Giants like Amazon and Walmart will tighten their grip over consumer spending.

Amazon and its fellow tech firms will also benefit from how the crisis reprograms consumer behavior. The pandemic has already been a boon to e-commerce, as people try to buy the things they need with a minimum of social interaction. Amazon recently announced it would hire one hundred thousand workers amid booming demand; Instacart, the online grocery delivery service, is adding three hundred thousand. This trend could very well become permanent. Consumers may come to prefer getting their groceries delivered rather than going to the supermarket, for instance, whether out of habit, convenience, or continued fear of infection. The service jobs of the future, then, will likely be concentrated in transportation and warehousing. A growing portion of the US working class will make a (meager, precarious) living packing and delivering the goods that people in extended periods of isolation need to survive.

The issue of survival brings us to another core theme of the coronavirus crisis: social reproduction. Social reproduction refers to the various systems—formal and informal, waged and unwaged—that make capitalism possible by raising, socializing, educating, healing, housing, and otherwise sustaining the workers whose labor power it runs on. These systems have long been under severe strain in the US. Stagnant wages and pitiful structures of social provision have placed most of the US working class on the brink of bankruptcy or worse, with nearly 80 percent of Americans living paycheck to paycheck.

The pandemic demolishes this rickety arrangement. Soaring demand for unemployment insurance and food stamps is pushing the parsimonious US welfare state well past the breaking point. Meanwhile, the fragile condition of the country’s highly financialized healthcare system—which has spent the last decade enriching executives and investors in a mergers and acquisitions spree—has been cast into stark relief.

But the pandemic isn’t just intensifying an existing crisis of social reproduction. The pandemic is also being intensified by the crisis. The poor quality of social-reproductive systems in the US has created the ideal conditions for contagion. To take one example, nursing homes emerged as hotspots early on. A large part of the blame lies with a wave of private-equity investment in the nursing home industry over the past decade, which has forced facilities across the country to cut costs in order to shovel more profits upwards. Many homes became extremely unsanitary as a result, with state inspections uncovering appalling cases of abuse and neglect. Now they have become major sites of infection.

A virus isn’t just a biological phenomenon, but a social one. The vulnerabilities it exploits to propagate itself aren’t just the properties of human cells, but how human societies are organized. Societies that organize themselves around the accumulation of capital—that is to say, capitalist ones—place themselves at risk, especially societies like the US, where accumulation takes a particularly brutal form.

There is a contradiction here: by undermining social reproduction, capitalism undermines its own stability. Squeezing the proletariat dry feeds the engine of capital up to a certain point—then it causes the machinery to seize up, as the feminist theorist Nancy Fraser has explained. The coronavirus crisis offers a vivid illustration of this dynamic. The extreme pressure that capital has placed on social reproduction in the US has produced a hospitable environment for a pandemic that is destroying the economy. Those private-equity capitalists, by strip-mining seniors for profit, have helped create a situation in which many of their fellow capitalists will no longer be able to set capital in motion.

For accumulation to resume its normal course, the virus must be contained: the robustness of the Chinese response, for example, is motivated not just by the desire to preserve the political legitimacy of the Communist Party but to restart industrial production. In the US, returning to business as usual will require, among other things, modest increases in public support for social reproduction. This may explain how Congress managed to pass a bill mandating ten days of paid sick leave for a subset of US workers so quickly in the first week of the pandemic. Letting workers get sick and die is acceptable; letting workers get sick and threaten the accumulation process is not.

In the industrial era, labor won concessions from capital because of a basic dependency: capitalists needed workers to run the factories. The economic slowdown since the 1970s has diminished this dependency, with the decline of manufacturing inaugurating an era of stagnation characterized by persistently low demand for labor, tilting the balance of power to capital’s advantage. The pandemic has the potential to partly reverse this development. Workers may hold less leverage over the accumulation process as workers, but they can now endanger that process as vectors of viral transmission. Perhaps this offers a new basis on which to win concessions.

Of course, workers can also make trouble the old-fashioned way: by engaging in disruptive action in their workplaces and their communities. The space for such action is likely to grow dramatically in the coming weeks and months. Imagine a near future of 30 percent unemployment, widespread food and housing insecurity, and millions dead from the pandemic and from the increased mortality of an overwhelmed healthcare system. These are essentially wartime conditions. They are the conditions under which revolution becomes, if not likely, at least thinkable.

In a crisis, the parameters of political possibility expand. Dozens of municipalities have halted evictions and utility shutoffs. Trump has instructed HUD to suspend foreclosures and evictions of homeowners with mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration. California plans to move thousands of homeless people into hotels, in some cases buying the hotels outright. New York City, Houston, and Detroit have made local bus service free.

But this is the only beginning. With pressure from below, these cracks in the common sense can be widened; indeed, the survival of a significant number of people probably depends on it. Towards that end, Bernie Sanders wants the federal government to send every household $2000 per month, invoke the Defense Production Act to force private firms to produce critical goods like masks and ventilators, and institute a national moratorium on evictions, foreclosures, and utility shutoffs, among other measures.

Given the pace of events, however, even these demands may look moderate within a short period of time. Among socialists, the crisis has spurred renewed calls to nationalize various sectors. Healthcare seems like an obvious candidate, particularly given the coming flood of hospital bankruptcies, the need for rational coordination of the kind that markets can’t provide, and the moral imperative to care for the many millions of Americans who are uninsured or underinsured.

Yet a concrete analysis of the concrete situation also requires something more. A perennial temptation among socialists is to pick up models from previous eras of struggle and apply them, without modification, to the problems of the present moment. This temptation grows in times of crisis, as a weakening of the status quo creates opportunities to put old socialist ideas into wider circulation. But times of crisis are also opportunities to generate new socialist ideas: new modes of organizing, new horizons for social transformation. The socialist tradition is a valuable source of inspiration and insight. It also does not hold the answers to every question posed by every conjuncture, for the simple reason that every conjuncture poses different questions.

Marx believed the answers to such questions must be found in the struggles of the working class. The working class was not just the only social force capable of constructing socialism—it was also the only social force capable of determining what socialism would look like. This process would be advanced through practice; that is, through the innumerable collisions and resistances of class struggle. Communism, he and Engels famously wrote, is not “an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself,” but “the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.” The task for socialists today is to locate the tremors of that movement and draw out its implicit content: to refine its raw materials into new strategies and programs and possible futures.

There will soon be no shortage of materials to work with, as the pandemic spins up a cycle of proletarian self-activity. Workers everywhere now have an urgent issue to agitate around—their health—and are already organizing on that basis. Wildcat strikes have broken out among garbage workers, auto workers, poultry workers, warehouse workers, and bus drivers. Amazon has seen a wave of militancy, forcing management to promise better health protections and to extend paid time off to its entire workforce. Instacart and Whole Foods workers have staged labor actions. Unionized nurses have rallied to protest shortages. Workers at GE have demanded repurposing jet engine factories to make ventilators. Mutual aid groups are emerging to coordinate grocery deliveries and childcare. Tenants across the country are organizing rent strikes. In Los Angeles, homeless families are seizing vacant homes.

These are strategies for survival but they are also, possibly, the seeds of a new world: sites of social power where people can collectively provision the resources they need and participate directly in the decisions that affect them. It is in these places and practices that the outlines of the next socialist project will be found. For this project to be credible to the people on whom it depends, it must be equal to the radicalism of our reality. It must offer a socialism that is not a branch of progressivism or a wing of the Democratic Party but a truly anti-systemic alternative, one that promises, however improbably, an end to the death cult of capital and the elevation of human health, dignity, and self-determination as the supreme organizing principles of our common life.

BEN TARNOFF

Ben Tarnoff is a founding editor of Logic.

A virus isn’t just a biological phenomenon, but a social one. The vulnerabilities it exploits to propagate itself aren’t just the properties of human cells, but how human societies are organized. Societies that organize themselves around the accumulation of capital—that is to say, capitalist ones—place themselves at risk, especially societies like the US, where accumulation takes a particularly brutal form.

There is a contradiction here: by undermining social reproduction, capitalism undermines its own stability. Squeezing the proletariat dry feeds the engine of capital up to a certain point—then it causes the machinery to seize up, as the feminist theorist Nancy Fraser has explained. The coronavirus crisis offers a vivid illustration of this dynamic. The extreme pressure that capital has placed on social reproduction in the US has produced a hospitable environment for a pandemic that is destroying the economy. Those private-equity capitalists, by strip-mining seniors for profit, have helped create a situation in which many of their fellow capitalists will no longer be able to set capital in motion.

For accumulation to resume its normal course, the virus must be contained: the robustness of the Chinese response, for example, is motivated not just by the desire to preserve the political legitimacy of the Communist Party but to restart industrial production. In the US, returning to business as usual will require, among other things, modest increases in public support for social reproduction. This may explain how Congress managed to pass a bill mandating ten days of paid sick leave for a subset of US workers so quickly in the first week of the pandemic. Letting workers get sick and die is acceptable; letting workers get sick and threaten the accumulation process is not.

In the industrial era, labor won concessions from capital because of a basic dependency: capitalists needed workers to run the factories. The economic slowdown since the 1970s has diminished this dependency, with the decline of manufacturing inaugurating an era of stagnation characterized by persistently low demand for labor, tilting the balance of power to capital’s advantage. The pandemic has the potential to partly reverse this development. Workers may hold less leverage over the accumulation process as workers, but they can now endanger that process as vectors of viral transmission. Perhaps this offers a new basis on which to win concessions.

Of course, workers can also make trouble the old-fashioned way: by engaging in disruptive action in their workplaces and their communities. The space for such action is likely to grow dramatically in the coming weeks and months. Imagine a near future of 30 percent unemployment, widespread food and housing insecurity, and millions dead from the pandemic and from the increased mortality of an overwhelmed healthcare system. These are essentially wartime conditions. They are the conditions under which revolution becomes, if not likely, at least thinkable.

In a crisis, the parameters of political possibility expand. Dozens of municipalities have halted evictions and utility shutoffs. Trump has instructed HUD to suspend foreclosures and evictions of homeowners with mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration. California plans to move thousands of homeless people into hotels, in some cases buying the hotels outright. New York City, Houston, and Detroit have made local bus service free.

But this is the only beginning. With pressure from below, these cracks in the common sense can be widened; indeed, the survival of a significant number of people probably depends on it. Towards that end, Bernie Sanders wants the federal government to send every household $2000 per month, invoke the Defense Production Act to force private firms to produce critical goods like masks and ventilators, and institute a national moratorium on evictions, foreclosures, and utility shutoffs, among other measures.

Given the pace of events, however, even these demands may look moderate within a short period of time. Among socialists, the crisis has spurred renewed calls to nationalize various sectors. Healthcare seems like an obvious candidate, particularly given the coming flood of hospital bankruptcies, the need for rational coordination of the kind that markets can’t provide, and the moral imperative to care for the many millions of Americans who are uninsured or underinsured.

Yet a concrete analysis of the concrete situation also requires something more. A perennial temptation among socialists is to pick up models from previous eras of struggle and apply them, without modification, to the problems of the present moment. This temptation grows in times of crisis, as a weakening of the status quo creates opportunities to put old socialist ideas into wider circulation. But times of crisis are also opportunities to generate new socialist ideas: new modes of organizing, new horizons for social transformation. The socialist tradition is a valuable source of inspiration and insight. It also does not hold the answers to every question posed by every conjuncture, for the simple reason that every conjuncture poses different questions.

Marx believed the answers to such questions must be found in the struggles of the working class. The working class was not just the only social force capable of constructing socialism—it was also the only social force capable of determining what socialism would look like. This process would be advanced through practice; that is, through the innumerable collisions and resistances of class struggle. Communism, he and Engels famously wrote, is not “an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself,” but “the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.” The task for socialists today is to locate the tremors of that movement and draw out its implicit content: to refine its raw materials into new strategies and programs and possible futures.

There will soon be no shortage of materials to work with, as the pandemic spins up a cycle of proletarian self-activity. Workers everywhere now have an urgent issue to agitate around—their health—and are already organizing on that basis. Wildcat strikes have broken out among garbage workers, auto workers, poultry workers, warehouse workers, and bus drivers. Amazon has seen a wave of militancy, forcing management to promise better health protections and to extend paid time off to its entire workforce. Instacart and Whole Foods workers have staged labor actions. Unionized nurses have rallied to protest shortages. Workers at GE have demanded repurposing jet engine factories to make ventilators. Mutual aid groups are emerging to coordinate grocery deliveries and childcare. Tenants across the country are organizing rent strikes. In Los Angeles, homeless families are seizing vacant homes.

These are strategies for survival but they are also, possibly, the seeds of a new world: sites of social power where people can collectively provision the resources they need and participate directly in the decisions that affect them. It is in these places and practices that the outlines of the next socialist project will be found. For this project to be credible to the people on whom it depends, it must be equal to the radicalism of our reality. It must offer a socialism that is not a branch of progressivism or a wing of the Democratic Party but a truly anti-systemic alternative, one that promises, however improbably, an end to the death cult of capital and the elevation of human health, dignity, and self-determination as the supreme organizing principles of our common life.

BEN TARNOFF

Ben Tarnoff is a founding editor of Logic.

4.07.2020