101 suspects arrested and rare cultural treasures recovered in huge global investigation

KARMA PRIMITIVE ACCUMULATION OF CAPITAL

Sam Jones in Madrid Fri 8 May 2020

Spanish police recovered a unique Tumaco gold mask. Photograph: Interpol

Two huge international police and customs operations targeting the trade in stolen artworks and archaeological artefacts have led to the arrest of 101 people and the recovery of more than 19,000 items, including a pre-Columbian gold mask, a carved Roman lion and thousands of ancient coins.

Two huge international police and customs operations targeting the trade in stolen artworks and archaeological artefacts have led to the arrest of 101 people and the recovery of more than 19,000 items, including a pre-Columbian gold mask, a carved Roman lion and thousands of ancient coins.

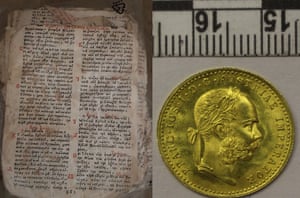

A Menaion from 1760 was seized in Romania as well as coins. Photograph: Interpol

The joint initiatives – which involved officers from Interpol, Europol, the World Customs Organization and many national police forces – focused on the criminal networks that steal from museums, plunder archaeological sites and take advantage of the chaos in war-afflicted countries to loot their cultural treasures.

Details of the two concurrent investigations carried out last autumn are emerging only now for operational reasons.

Police officers in Spain recovered several rare pre-Columbian objects at Madrid’s Barajas airport, including a unique Tumaco gold mask, gold figurines and pieces of ancient jewellery. All had been illegally acquired by looting in Colombia.

Three traffickers were arrested in Spain, while Colombian police carried out a series of searches in Bogotá, resulting in the confiscation of a further 242 pre-Columbian objects – the largest such seizure in the country’s history.

Colombian authorities retrieved 242 objects. Photograph: Interpol

Spain’s Guardia Civil police force said nine people were arrested in the country during the crackdown, and a Roman lion carved in limestone was recovered, as well as a frieze and three Roman columns.

Argentinian federal police seized 2,500 ancient coins, Latvian state police a further 1,375 coins, and Afghan customs officials at Kabul confiscated 971 cultural objects bound for Istanbul.

Other items recovered during the operations included fossils, paintings, ceramics and historical weapons

Cultural objects seized in Italy. Photograph: Interpol

Interpol said particular attention had been paid to monitoring online marketplaces. In the course of a “cyber patrol week”, officers led by the Italian carabinieri gathered information and identified targets that led to the seizure of 8,670 cultural objects offered for sale online.

“The number of arrests and objects show the scale and global reach of the illicit trade in cultural artefacts, where every country with a rich heritage is a potential target,” said Interpol’s secretary general, Jürgen Stock.

“If you then take the significant amounts of money involved and the secrecy of the transactions, this also presents opportunities for money laundering and fraud as well as financing organised crime networks.

”

Afghan customs recovered 971 cultural objects at Kabul airport. Photograph: Interpol

Europol said law enforcement agencies across the world needed to combat what it termed a “global phenomenon” that went well beyond the trade in looted artefacts, and that was closely related to other kinds of widespread criminal activity.

“Organised crime has many faces,” said its executive director, Catherine de Bolle. “The trafficking of cultural goods is one of them: it is not a glamorous business run by flamboyant gentlemen forgers, but by international criminal networks. You cannot look at it separately from combating trafficking in drugs and weapons: we know that the same groups are engaged, because it generates big money.”

Afghan customs recovered 971 cultural objects at Kabul airport. Photograph: Interpol

Europol said law enforcement agencies across the world needed to combat what it termed a “global phenomenon” that went well beyond the trade in looted artefacts, and that was closely related to other kinds of widespread criminal activity.

“Organised crime has many faces,” said its executive director, Catherine de Bolle. “The trafficking of cultural goods is one of them: it is not a glamorous business run by flamboyant gentlemen forgers, but by international criminal networks. You cannot look at it separately from combating trafficking in drugs and weapons: we know that the same groups are engaged, because it generates big money.”

_(ef04def6065c81ceb7d81c967f1e2095c2d32a4d).png?width=300&quality=85&auto=format&fit=max&s=e9b9293758a22d40baaefc91e2ea77e9)