Scarce medical oxygen worldwide leaves many gasping for life

By LORI HINNANT, CARLEY PETESCH and BOUBACAR DIALLO

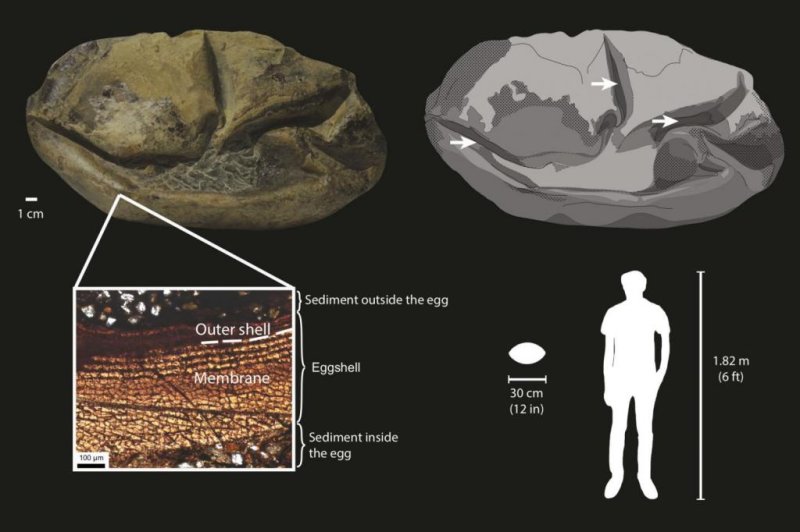

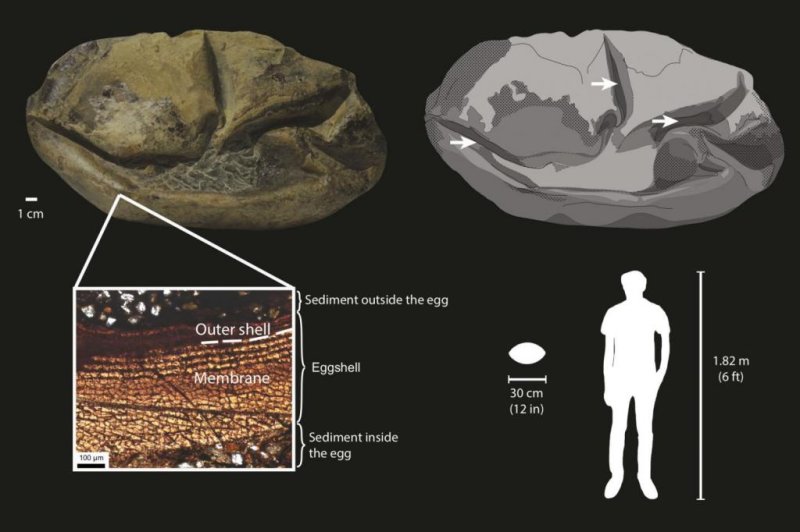

1 of 6Medical workers offload cylinders of oxygen at the Donka public hospital where coronavirus patients are treated in Conakry, Guinea, on Wednesday, May 20, 2020. Before the coronavirus crisis, the hospital in the capital was going through 20 oxygen cylinders a day. By May, the hospital was at 40 a day and rising, according to Dr. Billy Sivahera of the aid group Alliance for International Medical Action. Oxygen is the the facility's fastest-growing expense, and the daily deliveries of cylinders are taking their toll on budgets. (AP Photo/Youssouf Bah)

CONAKRY, Guinea (AP) — Guinea’s best hope for coronavirus patients lies inside a neglected yellow shed on the grounds of its main hospital: an oxygen plant that has never been turned on.

The plant was part of a hospital renovation funded by international donors responding to the Ebola crisis in West Africa a few years ago. But the foreign technicians and supplies needed to complete the job can’t get in under Guinea’s coronavirus lockdowns — even though dozens of Chinese technicians came in on a charter flight last month to work at the country’s lucrative mines. Unlike many of Guinea’s public hospitals, the mines have a steady supply of oxygen.

As the coronavirus spreads, soaring demand for oxygen is bringing out a stark global truth: Even the right to breathe depends on money. In much of the world, oxygen is expensive and hard to get — a basic marker of inequality both between and within countries.

In wealthy Europe and North America, hospitals treat oxygen as a fundamental need, much like water or electricity. It is delivered in liquid form by tanker truck and piped directly to the beds of coronavirus patients. Running short is all but unthinkable for a resource that literally can be pulled from the air.

In Spain, as coronavirus deaths climbed, engineers laid 7 kilometers (4 miles) of tubing in less than a week to give 1,500 beds in an impromptu hospital a direct supply of pure oxygen. Oxygen is also plentiful and brings the most profits in industrial use such as mining, aerospace, electronics and construction.

But in poor countries, from Peru to Bangladesh, it is in lethally short supply.

___

This story was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

___

In Guinea, oxygen is a costly challenge for government-funded medical facilities such as the Donka public hospital in the capital, Conakry. Instead of the new plant piping oxygen directly to beds, a secondhand pickup truck carries cylinders over potholed roads from Guinea’s sole source of medical-grade oxygen, the SOGEDI factory dating to the 1950s. Outside the capital, in medical centers in remote villages and major towns, doctors say there is no oxygen to be found at all.

The result is that the poor and the unlucky are left gasping for air.

FILE - In this Monday, June 8, 2020 file photo, people wearing masks amid the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic wait for hours, some for 10 hours, to refill their oxygen tanks at a shop in Callao, Peru. Long neglected hospitals around the world are reporting shortages of oxygen as they confront the spread of the disease. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

“Oxygen is one of the most important interventions, (but) it’s in very short supply,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. and current CEO of Resolve to Save Lives.

Alassane Ly, a telecommunications engineer and U.S. resident who split his time between the Atlanta suburbs and his homeland, boarded a flight to Guinea in February. He promised his wife and young daughters he’d be home by April to celebrate Ramadan with them.

Then he fell ill. Struggling to breathe and awaiting results for a coronavirus test, he went with his brother-in-law on May 4 to a nearby clinic on the outskirts of Conakry. But they weren’t equipped to help.

His condition worsening, he tried the Hospital of Chinese-Guinean Friendship, which also turned him away, his family says. Finally, his brother-in-law drove him through curfew checkpoints to the intensive care unit of the Donka hospital for the oxygen he had sought all day.

It was apparently too little and too late. Within hours, he was dead. Six weeks later, his coronavirus test came back positive.

His death has sparked a furor in Guinea. The country’s health minister, Rémy Lamah, maintained that Ly got excellent care at Donka.

But when Lamah himself came down with coronavirus this month, he, like other top government officials, went to a military hospital only for VIPs.

Ly’s widow, Taibou, said if Lamah was so confident about Donka, he would have gone there himself. She accepts her husband’s death as God’s will, but said she cannot accept a medical system that failed.

“One life is not worth more than another,” she said from her home in Atlanta. “They will have to live with their conscience.”

FILE - In this Thursday, April 2, 2020 file photo, patients lie in beds at a temporary field hospital in the Ifema convention center in Madrid, Spain. As coronavirus deaths climbed, engineers laid 7 kilometers (4 miles) of tubing in less than a week to give 1,500 beds in the impromptu facility a direct supply of pure oxygen. (AP Photo/Manu Fernandez)

_____

For many severe COVID patients, hypoxia — radically low blood-oxygen levels — is the main danger. Only pure oxygen in large quantities buys the time they need to recover. Oxygen is also used for the treatment of respiratory diseases such as pneumonia, the single largest cause of death in children worldwide.

Yet until 2017, oxygen wasn’t even on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. In vast parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Asia, that meant there was little money from international donors and little pressure on governments to invest in oxygen knowledge, access or infrastructure.

“Oxygen has been missing on the global agenda for decades,” said Leith Greenslade, a global health activist with the coalition Every Breath Counts.

The issue got more attention after British Prime Minister Boris Johnson narrowly survived a bout of coronavirus, crediting his recovery to the National Health Service and “liters and liters of oxygen.” But Johnson is a prominent figure in one of the world’s richest countries.

Unlike for vaccines, clean water, contraception or HIV medication, there are no global studies to show how many people lack oxygen treatment — only broad estimates that suggest at least half of the world’s population does not have access to it.

In the few places where in-depth studies have been carried out, the situation looks dire. In Congo, only 2% of health care facilities have oxygen; in Tanzania, it’s 8%, and in Bangladesh, 7%, according to limited surveys for USAID. Most countries never even get surveyed.

In Bangladesh, the lack of a centralized system for the delivery of oxygen to hospitals has led to a flourishing market in the sale of cylinders to homes.

Abu Taleb said he used to sell or rent out up to 10 cylinders a month at his medical supply shop; now it’s at least 100. Courts have sentenced about a dozen people for selling and stockpiling unauthorized oxygen cylinders, often at exorbitant prices.

Tannu Rahman, a housewife, waited three days to get a cylinder of oxygen for her brother-in-law, who has been infected with coronavirus in the capital, Dhaka. Rahman said they were in complete despair as “nobody came forward,” even though she offered to pay twice the regular price.

Finally, she managed to buy a cylinder at three times the price, but her brother-in-law is now in the hospital in critical condition.

“We don’t know what is waiting for us,” she said. “We are very worried.”

In Peru, which recently surpassed Italy in its number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, the president has ordered industrial plants to ramp up production for medical use or buy oxygen from abroad. He allocated about $28 million for oxygen tanks and new plants.

Some hospitals have oxygen plants that don’t work or can’t produce enough, while others have no plants at all. In the city of Tarapoto in northern Peru, relatives of COVID patients who died from lack of oxygen protested outside a hospital with a plant that does not work, banging pots and pans. The government has flown in tanks of oxygen by air and is expected to install a new plant.

Annie Flores has lost two relatives to COVID oxygen shortages. She said the family embarked on a desperate quest to buy oxygen after being told the hospital didn’t have any. Price gouging was rampant, with tanks going for six times the usual amount.

She said her sister-in-law’s aunt died Sunday, 30 minutes after an oxygen provider refused to refill a tank the family had bought elsewhere.

“I’m anxious and having panic attacks,” said Flores, a special events planner. “The amount of oxygen being brought here isn’t enough.”

In Sierra Leone, neighboring Guinea, just three medical oxygen plants serve 17 million people. One inside the main Connaught Hospital broke down for nearly a week, as COVID cases mounted. Even now, with the plant working again, there are shortages of cylinders to fill.

FILE - In this Tuesday, March 31, 2020 file photo, medical oxygen tanks for respiratory treatment are prepared in Cinisello Balsamo, near Milan, Northern Italy. In wealthy Europe and North America, hospitals treat oxygen as a fundamental need, much like water or electricity. But in poor countries, it is in lethally short supply. (Claudio Furlan/LaPresse via AP)

Everywhere that oxygen is scarce, pulse oximeters to measure blood-oxygen levels are even scarcer, making it nearly impossible for doctors and nurses to know when a patient has been stabilized. By the time lips turn blue, a frequent measure used, a patient is usually beyond saving.

Some places have made progress, largely thanks to local activists who have pushed for more oxygen plants and better access outside just the largest cities. Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda all have made it a priority, according to Dr. Bernard Olayo of the Center for Public Health and Development in East Africa.

But in Guinea, not a single hospital bed has a direct oxygen supply, and the daily deliveries of cylinders are taking their toll on budgets, with each one costing $115. A standard cylinder costs on average $48 to $60 in Africa, compared to the same amount of oxygen for between $3 and $5 in wealthy countries, Olayo said.

Dr. Aboubacar Conté, a surgeon who runs Guinea’s health services, said four hospitals in outlying cities will eventually get their own on-site plants to ease what he acknowledged is a need for oxygen outside the capital.

“We just need the financing for the need to improve the health of the population,” said Conté, who was diagnosed with coronavirus the day after speaking with The Associated Press by phone. “These are big investments that you will see in time.”

____

Roughly the size of Britain, Guinea reaches out into West Africa like a hook, sharing borders with six countries. It is believed to have half the world’s reserves of bauxite, the base material for aluminum, as well as scattered mines for gold and diamonds. But mineral wealth has not translated into health for its 12 million residents, with one in 10 children dying before the age of 5.

Guinea’s landscape ranges from coastlines to hills to rainforests, with sparse dusty unpaved roads that fill with water in the rain. In a good all-terrain vehicle, crossing Guinea takes four days; in the rainy season, much longer.

Inequality is built into the distance along the mud roads. The SOGEDI oxygen factory delivers only to Conakry, and sparingly, for few medical centers even in the capital have the means to pay for its cylinders and so send away patients they cannot help.

Doctors outside Conakry say oxygen is just one of the most basic of necessities they do without, including general painkillers, thermometers and reliable electricity.

“It’s a matter of priority for us. ... We have nothing,” said Dr. Theophile Goto Monemou, the chief medical officer at Sangaredi Community Hospital, a stark building with a handful of physicians. “All we can do is send someone elsewhere if they are in need.”

In mid-June, at least two people tested positive for COVID-19 there. One was driven more than six hours by ambulance for treatment, according to Sangaredi Mayor Mamadou Bah.

Guinea’s official coronavirus tally is about, 5,000 coronavirus cases and 28 dead. The tally is an undercount as testing is limited.

Dr. Fode Kaba, a cardiologist at a public hospital in Ratoma, an outlying neighborhood of Conakry, said he has no oxygen at hand and no intensive care beds. When people seeking urgent care can’t breathe, he calls an ambulance to send them to Donka, about 20 minutes away, and hopes for the best. But, he acknowledged, “If you don’t get it right away, it’s death.”

Guinea was the source of the Ebola epidemic that began in 2014 and spread through West Africa, ultimately killing more than 11,000 people over two years. Dr. Amer Sattar, a public health expert who worked in Guinea during that time and is there still, said even after Ebola, the country failed to do what was needed for basic health care.

He said the coronavirus crisis is a chance for international donors and governments alike to invest in the long term “so that we’re ready for the next pandemic.”

FILE - In this Friday, May 22, 2020 file photo, patients testing positive for COVID-19 breathe in oxygen in the emergency area of the Guillermo Almenara hospital in Lima, Peru. As the coronavirus spreads, soaring demand for oxygen is bringing out a stark global truth: Even the right to breathe depends on money. In much of the world, oxygen is expensive and hard to get — a basic marker of inequality both between and within countries. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Medical oxygen comes in liquid and compressed forms.

Liquid oxygen is what wealthy countries largely use. Air is chilled to minus 186 degrees Celsius, so that the oxygen condenses into a liquid in much the same way dew forms in cool night air. It is then pumped into a truck-sized double-thick vacuum flask on wheels and sent to hospitals. There, pumps warm it back into a gas.

Compressed oxygen is pressurized into cylinders about the size of a small adult. Each weighs about 50 kilograms (110 pounds).

Before the coronavirus crisis, the Donka hospital in Conakry went through 20 oxygen cylinders a day. By May, the hospital was at 40 a day and rising, for a total of more than $130,000 a month, according to Dr. Billy Sivahera of the aid group Alliance for International Medical Action. Oxygen is the hospital’s fastest-growing expense.

The system for delivering oxygen cylinders is clunky and expensive. At least once a day, and sometimes twice, a 23-year-old driver takes a truckload of white cylinders full of oxygen from the SOGEDI factory to Donka, and picks up the empties to be refilled. It can carry a couple of dozen cylinders at a time.

The arrival of the cylinders is marked on a clipboard, and half a dozen young men shoulder them off the truck and reload used ones. The oxygen goes almost exclusively to COVID patients, with a canister sometimes split between beds to make it last a little longer. The hospital has also brought in oxygen concentrators, portable and usually temporary devices where the purity and volume of oxygen is lower.

Everyone is counting on the hospital’s oxygen plant to start up, but no one knows when. There is no budget for a charter plane for technicians and no date for a resumption of commercial flights. In the meantime, the wall hookups that someday may carry pure oxygen to the beds gather dust.

“We need more access to oxygen because the consequences are serious,” Sivahera said. “We need them to come finish this.”

___

Hinnant reported from Paris; Petesch reported from Dakar. Julhas Alam in Dhaka, Bangladesh; Christine Armario in Bogota, Colombia; and Youssouf Bah in Conakry, Guinea, contributed to this report.

___

Follow AP pandemic coverage at http://apnews.com/VirusOutbreak and https://apnews.com/UnderstandingtheOutbreak