SPENT JULY 1, CANADA DAY

VENCEREMOS FOR BROCCOLI

IN MEMORY OF DAD AND FIDEL

Loz diez millones van! Fidel Castro cuts cane, 1970

FIDEL THE GODFATHER

FIDEL WAS A PALLBEARER

AT TRUDEAU SR. FUNERAL

Loz diez millones van! Fidel Castro cuts cane, 1970

FIDEL THE GODFATHER

FIDEL WAS A PALLBEARER

AT TRUDEAU SR. FUNERAL

The Venceremos Brigade

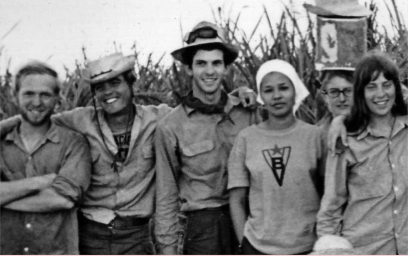

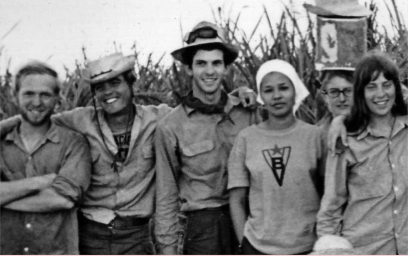

Dick Cluster, third from left, with Cuban and u.s. fifth brigade members of the venceremos brigade. From left to right: Steve, Alberto, Dick, lázara and Nancy. Photo courtesy of Dick Cluster

A 60s Political Journey

By Dick Cluster

In the spring of 1961, as a 14-year-old in Baltimore, Maryland, interested in current events, I read in the New York Times about Cubans fighting for freedom at a place called the Bay of Pigs, against a dictatorship that had hijacked a popular revolution. When the forces of good failed to triumph at the Bay of Pigs, I was shocked. A classmate of mine—a precocious member of the Young Socialist Alliance— told me that the operation had been run by the CIA. I could not believe. Hadn’t Adlai Stevenson denied this at the United Nations? Hadn’t the New York Times and other media reported the invasion was a spontaneous action by freedom-loving Cubans?

I tell this story to explain the political journey that led not only me but many of the 216 members of the first contingent of the Venceremos Brigade to violate the warning on our U.S. passports that stated they were “not valid for travel” to the “restricted countries and areas of Cuba, Mainland China, North Korea, and North Viet Nam.” In the years between 1961 and 1969, the Viet Nam war had taught us that what the mainstream media and our government officials said about our country’s foreign policy might not only be mistaken, but might even be a cynical and conscious effort to mislead us in both senses of the word.

Thus the lure of visiting Cuba to cut sugar cane in the Ten Million Ton harvest of 1969-70 was irresistible. It was a chance to see for ourselves whether the devil really had horns and a tail— or, on the contrary, was an angel with a halo. The prospect of doing manual labor with ordinary Cubans meant we were more likely to see the real Cuba than if we sat in formal meetings and speeches. The journey also promised a limited and measurable task—how much cane did we cut—as compared to the complex and sometimes daunting challenge of ending the war or combating racism or bringing radical change to our society. So we flew to Mexico City—the only air link to Havana in the Western Hemisphere at the time—where we were photographed by Mexican intelligence officers and had “Mexico D.F. CUBA” stamped in large purple letters on our passports so our transgression would not go unnoticed at home. And so eventually we returned, three months later, via Cuban freighter to the Canadian Atlantic port of St. John. In between, we cut cane, asked, listened, looked and argued (mostly with each other).

We lived at the Campamento Brigada Venceremos in rural Havana province near the Matanzas border, flat cane-growing land since its deforestation long ago in the days of the Spanish colony. We lived in canvas tents and gathered in palm thatch meeting and mess halls, the 216 of us and 70 Cuban Young Communists selected to work with us and teach us about the Revolution. In our final two weeks, they and we toured the island by schoolbus, staying in other work camps and recently constructed college dorms. Here are some thoughts I took away from this experience at the time.

The revolution (that is, the rebellion against Batista and its subsequent socialist institutionalization) had been a great exercise in social mobility and redistribution: Lázara, for example, was the daughter of factory worker who had been imprisoned for trade union activity; now she was teaching high school and studying journalism at the university. Alberto’s father had been a truckdriver; he was teaching high school history, studying art and literature, designing posters. Hugo had been a clothing worker himself; now he was an economist. Former mansions in Havana were dorms for students from the countryside. Our Cuban colleagues debated which former luxury tourist hotel they liked best, since all had been the scene of conferences and retreats. In Oriente we could drive to remote villages, previously isolated from all social services; now we found a clinic, a bookstore, a school.

Great changes in consciousness were possible, and had occurred. In the 50s, Cuba had been as anti-communist as the United States. Now, our new friends and their families approved the revolutionary reforms. At a youth work camp we visited—much like ours except it had permanent barracks, a longer workday, and did not have ice cream as part of the daily rations—I met a teenager doing guard duty at her barracks. Only the two of us were there, no minders of any sort. She told me her mother had just left for the United States, but she had chosen to stay. “I love my mother,” she said, “but I love the revolution more.”

Communism did not have to be Stalinist. That is to say, it didn’t need to be a carbon-copy of the U.S.S.R., its culture gray, dogmatic, and always politically correct. In off hours, the camp seemed to teem with spontaneity. If someone had a wooden box and two hands, there would be drumming, music, dancing. Movie posters, even propaganda posters, as well as the new paintings in the Havana fine arts museum owed more to San Francisco psychedelia than Soviet socialist realism.

During our travels, our Cuban friends bought up copies of a new novel by a Colombian novelist, published by Casa de las Américas in Havana, Cien Años de Soledad. Later, in Santiago de Cuba, a medical student who had very tentatively suggested we might consider going home and waging armed struggle to bring socialism to the United States, made us a present of his dog-eared copy of the same book. We asked these enthusiasts about the novel, expecting a revolutionary tale. “Well, it’s about this village. . . . Well, you have to read it, it’s very hard to explain,”they replied, neither the village of Macondo nor the concept of “magic realism” being a doctrinal concept that fit into any prepackaged phrase.

An international new wind could be felt in the contingents participating in the harvest from all over the world, including Vietnamese from both the north and south. However, the most telling vignette was about a personal reunion. Vic, from San Francisco, one of the oldest and most grizzled brigadistas, had fought for the Spanish Republic in the International Brigades. When asked, “what are your politics now?” (a key question for identifying factions and tendencies with which people were associated back home), he would say, “I’m a drunk.” No communist orthodoxy or New Leftist utopianism for him. One day a group of Bulgarian canecutters came to visit and work; with them came their embassy’s cultural attaché. He and Vic (I was told, because I didn’t see it) fell into each other’s arms, in tears. They had not seen each other since Spain, and here they were, at the heart of something that was a continuation, yet different and new. There were some discordant notes, of course. In El Uvero in Oriente, though we met older women who had learned to read in the Literacy Campaign, the bookstore was full of unsold books—and our comrades were ecstatic about finding such a trove, including the sought-after García Márquez novel. When the camp leadership made “proposals” about changes in routine, production targets, and the like, there were no arguments for or against, only a revolutionary duty to rise to the occasion. Trade union leaders we met patiently explained to us that there could be no conflicts between workers and management because enterprises were owned by the revolution which was the workers themselves. All of this, however, paled before the evident enthusiasm for making a new country, not only on the part of the Young Communists but, if more muted by everyday life concerns, of many people we met a random too. That vision continued to inspire me, and it continued to inspire many of us—not only in radical organizing but in political, service, and education work of many sorts since.

Readers of ReVista will be well aware that Cuba today is not the future for which our friends on the brigade were working so hard. The harvest did not meet the goal; a more repressive policy in the arts dominated the 1970s; years of significant economic improvement in the later 70s and 80s were reversed in the 1990s with the end of Soviet aid. The world that our friends’ children got was not the one their parents had planned on bequeathing. (Aside: Nonetheless, I’m quite impressed with the way our friends’ children turned out, and the children of others like them, though that discussion does not fit in this article.)

The Cuban brigadistas with whom I was able to stay in touch now have politics that range from the hope of reinventing Cuban socialism within Fidelismo to constant criticism or cynicism, excluding only association with the U.S.-backed opposition either in Cuba or in Florida. Lázara died in the early ‘90s; by then she had a reputation, among Cubans who casually knew her, as an “honest dogmatist.” But this was her parting thought not long before she died: “We have not resolved the relationship between el hombre (man/woman/the individual) and el poder (the apparatus of power).” In those same years Juan, my former cane-cutting partner who now worked as a translator and interpreter, tried at first to put the best face on things. Then one day he said, “There’s no point in my telling you what I told the visiting Turkish journalists today. You’ve been living here a while, and you know how things are.” A few years later, his wife won the U.S. visa lottery and he somewhat reluctantly moved to Miami, to join many of her relatives and some of his. His plan for this new epoch of his life was to stay out of politics and keep his opinions to himself.

However, this was not what surprised me in my reencounters with Cuban brigadistas in the 90s and since. Rather I was struck that, without exception, they said that what they had told us in 1969-70 was the truth as they saw and felt it then. No one had been treating us like Turkish journalists. What we saw was not completely representative, but it was real. Even more surprisingly, the experience had been as special and intense for the Cuban brigadistas as for us. The explanation for this consensus seemed to boil down to two things:

We took what they were doing seriously. For them as for us, the utopian project was much in need of validation, and formal delegations and slogans about international solidarity were not completely doing the trick. Further, since the 19th century the United States has always had a Janus-faced character in the Cuban imagination—a potentially dominating power to be resisted, but a source of modernity and fresh ideas and part of Cuba’s synthesizing Spanish-African culture too. That we took our Cuban co-workers so seriously confirmed the seriousness with which they wanted to take themselves.

They were challenged and excited by our cultural radicalism. Cuban youth in general were curious, or challenged, or puzzled about U.S. “hippies,” but in the day to day exchanges on the Brigade, our counter-culture got more real. Our drug-taking never made any sense to them. Those who spoke English did enjoy picking up our foul language, “fucking this” and “motherfucking that.”.But more deeply, something about our notions of cultural liberation, of new gender roles, of societal reinvention outside the spheres of pure politics and economics—something about that changed their sense of what was possible, or gave them something new to grapple with. One example out of many is the protest waged by North American women against being consigned to piling cane rather than cutting it, and issue on which the Cubans eventually gave in., Similarly, they were stimulated by the process of responding to our incessant questions about how their system worked (and how it didn’t work).

I think we can take the two-way intensity of that trans-national, trans-cultural exchange as another lasting moral of the story. The world is no less in need now than then of new systems, paradigms, visions, call it what you will. Our country, certainly, needs to overcome its arrogance and isolation. Others still need to process their love-hate relationships with us.

Dick Cluster is a writer, teacher, and translator whose most recent book, The History of Havana (Palgrave-Macmillan 2006, 2008), co-authored with Rafael Hernández, is a social history of the Cuban capital. He is associate director of the University Honors Program at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/venceremos-brigade

Printer-friendly version

A GREAT LEFT SITE AT HARVARD!!!!

https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/sixties-winter-2009

JUST KIDDING

HARVARD ALSO HAS A KICK ASS

LABOR STUDIES , WOMEN'S STUDIES, AND UKRAINIAN STUDIES PROGRAMS

AND PROBABLY A COUPLE MORE I DON'T KNOW ABOUT.

Sandy Lillydahl Venceremos Brigade Photograph Collection

Dick Cluster, third from left, with Cuban and u.s. fifth brigade members of the venceremos brigade. From left to right: Steve, Alberto, Dick, lázara and Nancy. Photo courtesy of Dick Cluster

A 60s Political Journey

By Dick Cluster

In the spring of 1961, as a 14-year-old in Baltimore, Maryland, interested in current events, I read in the New York Times about Cubans fighting for freedom at a place called the Bay of Pigs, against a dictatorship that had hijacked a popular revolution. When the forces of good failed to triumph at the Bay of Pigs, I was shocked. A classmate of mine—a precocious member of the Young Socialist Alliance— told me that the operation had been run by the CIA. I could not believe. Hadn’t Adlai Stevenson denied this at the United Nations? Hadn’t the New York Times and other media reported the invasion was a spontaneous action by freedom-loving Cubans?

I tell this story to explain the political journey that led not only me but many of the 216 members of the first contingent of the Venceremos Brigade to violate the warning on our U.S. passports that stated they were “not valid for travel” to the “restricted countries and areas of Cuba, Mainland China, North Korea, and North Viet Nam.” In the years between 1961 and 1969, the Viet Nam war had taught us that what the mainstream media and our government officials said about our country’s foreign policy might not only be mistaken, but might even be a cynical and conscious effort to mislead us in both senses of the word.

Thus the lure of visiting Cuba to cut sugar cane in the Ten Million Ton harvest of 1969-70 was irresistible. It was a chance to see for ourselves whether the devil really had horns and a tail— or, on the contrary, was an angel with a halo. The prospect of doing manual labor with ordinary Cubans meant we were more likely to see the real Cuba than if we sat in formal meetings and speeches. The journey also promised a limited and measurable task—how much cane did we cut—as compared to the complex and sometimes daunting challenge of ending the war or combating racism or bringing radical change to our society. So we flew to Mexico City—the only air link to Havana in the Western Hemisphere at the time—where we were photographed by Mexican intelligence officers and had “Mexico D.F. CUBA” stamped in large purple letters on our passports so our transgression would not go unnoticed at home. And so eventually we returned, three months later, via Cuban freighter to the Canadian Atlantic port of St. John. In between, we cut cane, asked, listened, looked and argued (mostly with each other).

We lived at the Campamento Brigada Venceremos in rural Havana province near the Matanzas border, flat cane-growing land since its deforestation long ago in the days of the Spanish colony. We lived in canvas tents and gathered in palm thatch meeting and mess halls, the 216 of us and 70 Cuban Young Communists selected to work with us and teach us about the Revolution. In our final two weeks, they and we toured the island by schoolbus, staying in other work camps and recently constructed college dorms. Here are some thoughts I took away from this experience at the time.

The revolution (that is, the rebellion against Batista and its subsequent socialist institutionalization) had been a great exercise in social mobility and redistribution: Lázara, for example, was the daughter of factory worker who had been imprisoned for trade union activity; now she was teaching high school and studying journalism at the university. Alberto’s father had been a truckdriver; he was teaching high school history, studying art and literature, designing posters. Hugo had been a clothing worker himself; now he was an economist. Former mansions in Havana were dorms for students from the countryside. Our Cuban colleagues debated which former luxury tourist hotel they liked best, since all had been the scene of conferences and retreats. In Oriente we could drive to remote villages, previously isolated from all social services; now we found a clinic, a bookstore, a school.

Great changes in consciousness were possible, and had occurred. In the 50s, Cuba had been as anti-communist as the United States. Now, our new friends and their families approved the revolutionary reforms. At a youth work camp we visited—much like ours except it had permanent barracks, a longer workday, and did not have ice cream as part of the daily rations—I met a teenager doing guard duty at her barracks. Only the two of us were there, no minders of any sort. She told me her mother had just left for the United States, but she had chosen to stay. “I love my mother,” she said, “but I love the revolution more.”

Communism did not have to be Stalinist. That is to say, it didn’t need to be a carbon-copy of the U.S.S.R., its culture gray, dogmatic, and always politically correct. In off hours, the camp seemed to teem with spontaneity. If someone had a wooden box and two hands, there would be drumming, music, dancing. Movie posters, even propaganda posters, as well as the new paintings in the Havana fine arts museum owed more to San Francisco psychedelia than Soviet socialist realism.

During our travels, our Cuban friends bought up copies of a new novel by a Colombian novelist, published by Casa de las Américas in Havana, Cien Años de Soledad. Later, in Santiago de Cuba, a medical student who had very tentatively suggested we might consider going home and waging armed struggle to bring socialism to the United States, made us a present of his dog-eared copy of the same book. We asked these enthusiasts about the novel, expecting a revolutionary tale. “Well, it’s about this village. . . . Well, you have to read it, it’s very hard to explain,”they replied, neither the village of Macondo nor the concept of “magic realism” being a doctrinal concept that fit into any prepackaged phrase.

An international new wind could be felt in the contingents participating in the harvest from all over the world, including Vietnamese from both the north and south. However, the most telling vignette was about a personal reunion. Vic, from San Francisco, one of the oldest and most grizzled brigadistas, had fought for the Spanish Republic in the International Brigades. When asked, “what are your politics now?” (a key question for identifying factions and tendencies with which people were associated back home), he would say, “I’m a drunk.” No communist orthodoxy or New Leftist utopianism for him. One day a group of Bulgarian canecutters came to visit and work; with them came their embassy’s cultural attaché. He and Vic (I was told, because I didn’t see it) fell into each other’s arms, in tears. They had not seen each other since Spain, and here they were, at the heart of something that was a continuation, yet different and new. There were some discordant notes, of course. In El Uvero in Oriente, though we met older women who had learned to read in the Literacy Campaign, the bookstore was full of unsold books—and our comrades were ecstatic about finding such a trove, including the sought-after García Márquez novel. When the camp leadership made “proposals” about changes in routine, production targets, and the like, there were no arguments for or against, only a revolutionary duty to rise to the occasion. Trade union leaders we met patiently explained to us that there could be no conflicts between workers and management because enterprises were owned by the revolution which was the workers themselves. All of this, however, paled before the evident enthusiasm for making a new country, not only on the part of the Young Communists but, if more muted by everyday life concerns, of many people we met a random too. That vision continued to inspire me, and it continued to inspire many of us—not only in radical organizing but in political, service, and education work of many sorts since.

Readers of ReVista will be well aware that Cuba today is not the future for which our friends on the brigade were working so hard. The harvest did not meet the goal; a more repressive policy in the arts dominated the 1970s; years of significant economic improvement in the later 70s and 80s were reversed in the 1990s with the end of Soviet aid. The world that our friends’ children got was not the one their parents had planned on bequeathing. (Aside: Nonetheless, I’m quite impressed with the way our friends’ children turned out, and the children of others like them, though that discussion does not fit in this article.)

The Cuban brigadistas with whom I was able to stay in touch now have politics that range from the hope of reinventing Cuban socialism within Fidelismo to constant criticism or cynicism, excluding only association with the U.S.-backed opposition either in Cuba or in Florida. Lázara died in the early ‘90s; by then she had a reputation, among Cubans who casually knew her, as an “honest dogmatist.” But this was her parting thought not long before she died: “We have not resolved the relationship between el hombre (man/woman/the individual) and el poder (the apparatus of power).” In those same years Juan, my former cane-cutting partner who now worked as a translator and interpreter, tried at first to put the best face on things. Then one day he said, “There’s no point in my telling you what I told the visiting Turkish journalists today. You’ve been living here a while, and you know how things are.” A few years later, his wife won the U.S. visa lottery and he somewhat reluctantly moved to Miami, to join many of her relatives and some of his. His plan for this new epoch of his life was to stay out of politics and keep his opinions to himself.

However, this was not what surprised me in my reencounters with Cuban brigadistas in the 90s and since. Rather I was struck that, without exception, they said that what they had told us in 1969-70 was the truth as they saw and felt it then. No one had been treating us like Turkish journalists. What we saw was not completely representative, but it was real. Even more surprisingly, the experience had been as special and intense for the Cuban brigadistas as for us. The explanation for this consensus seemed to boil down to two things:

We took what they were doing seriously. For them as for us, the utopian project was much in need of validation, and formal delegations and slogans about international solidarity were not completely doing the trick. Further, since the 19th century the United States has always had a Janus-faced character in the Cuban imagination—a potentially dominating power to be resisted, but a source of modernity and fresh ideas and part of Cuba’s synthesizing Spanish-African culture too. That we took our Cuban co-workers so seriously confirmed the seriousness with which they wanted to take themselves.

They were challenged and excited by our cultural radicalism. Cuban youth in general were curious, or challenged, or puzzled about U.S. “hippies,” but in the day to day exchanges on the Brigade, our counter-culture got more real. Our drug-taking never made any sense to them. Those who spoke English did enjoy picking up our foul language, “fucking this” and “motherfucking that.”.But more deeply, something about our notions of cultural liberation, of new gender roles, of societal reinvention outside the spheres of pure politics and economics—something about that changed their sense of what was possible, or gave them something new to grapple with. One example out of many is the protest waged by North American women against being consigned to piling cane rather than cutting it, and issue on which the Cubans eventually gave in., Similarly, they were stimulated by the process of responding to our incessant questions about how their system worked (and how it didn’t work).

I think we can take the two-way intensity of that trans-national, trans-cultural exchange as another lasting moral of the story. The world is no less in need now than then of new systems, paradigms, visions, call it what you will. Our country, certainly, needs to overcome its arrogance and isolation. Others still need to process their love-hate relationships with us.

Dick Cluster is a writer, teacher, and translator whose most recent book, The History of Havana (Palgrave-Macmillan 2006, 2008), co-authored with Rafael Hernández, is a social history of the Cuban capital. He is associate director of the University Honors Program at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/venceremos-brigade

Printer-friendly version

A GREAT LEFT SITE AT HARVARD!!!!

https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/sixties-winter-2009

JUST KIDDING

HARVARD ALSO HAS A KICK ASS

LABOR STUDIES , WOMEN'S STUDIES, AND UKRAINIAN STUDIES PROGRAMS

AND PROBABLY A COUPLE MORE I DON'T KNOW ABOUT.

Sandy Lillydahl Venceremos Brigade Photograph Collection

Read collection overview

A 1969 graduate of Smith College and member of Students for a Democratic Society, Sandy Lillydahl took part in the second contingent of the Venceremos Brigade. Between February and April 1970, Lillydahl and traveled to Cuba as an expression of solidarity with the Cuban people and to assist in the sugarcane harvest.

The 35 color snapshots that comprise the Lillydahl collection document the work of during the New England contingent of the second Venceremos Brigade as they worked the sugarcane fields in Aguacate, Cuba, and toured the country. Each image is accompanied by a caption supplied by Lillydahl in 2005, describing the scene and reflecting on her experiences, and the collection also includes copies of the file kept by the FBI on Lillydahl, obtained by her through the Freedom of Information Act in 1975

Background on Sandy Lillydahl

Jamie Lasalle, cutting cane

In 1969, the antiwar activist and former president of Students for a Democratic Society, Carl Oglesby, proposed that the SDS should organize a contingent of American students to travel to Cuba as a gesture of revolutionary solidarity. As guests of the Cuban government, members of what would be called the Venceremos Brigade would go not as tourists, but as workers intending to assist the struggling nation reach its ambitious goal of harvesting 10 million tons of sugarcane for export, allowing them to raise capital to shore up the economy and lessen dependence on the Soviet Union. Following on the heels of the First Brigade in 1969, the Venceremos Brigade became an annual project, sending thousands of American students over the years to work and to learn about Cuban history and culture.

Among the participants on the Second Brigade was a recent graduate of Smith College, Sandy Lillydahl. A native of Wisconsin, Lillydahl had become involved in SDS as an undergraduate and shared in the group's radical opposition to the war in Vietnam and their desire to remake American society on more egalitarian grounds.

In February 1970, nearly 1,000 volunteers from across the United States traveled to Cuba in two large groups defying the imposition of a comprehensive embargo on travel and trade. Several hundred Brigadistas from the western states flew to Havana by way of Mexico City, while approximately 500 participants from the east traveled to New Brunswick, Canada, to board a freighter, the Luis Arcos Bergnes, southward.

Once they arrived in Cuba, the participants were subdivided into smaller Brigades based on their region of origin, with New Englanders comprising Brigades 5 and 6 -- the latter Lillydahl's Brigade.

After harvesting sugarcane in Aguacate, southeast of Havana, for several weeks, the Brigade spent two weeks touring the country from Santiago de Cuba and Oriente Province to Havana, visiting schools and other facilities to learn about Cuba's revolutionary project. After returning to the United States, Lillydahl, like nearly every other member of the Venceremos Brigade, was approached by the FBI about her involvement. She refused to cooperate.

Scope of collection

The 35 color snapshots that comprise the Lillydahl collection document the work of during the New England contingent of the second Venceremos Brigade as they worked the sugarcane fields in Aguacate, Cuba, and toured the country. Each image is accompanied by a caption supplied by Lillydahl in 2005, describing the scene and reflecting on her experiences, and the collection also includes copies of the file kept by the FBI on Lillydahl, obtained by her through the Freedom of Information Act in 1975.

ONCE UPON A TIME MICHAEL KINSLEY WAS A HARVARD LIBERAL, FOUNDER OF SLATE

Venceremos Brigade Saw Joy in Cuba

By Michael E. Kinsley

February 21, 1970

Six members of the Venceremos Brigade, who returned last week from eight weeks of touring and harvesting sugar cane in Cuba, faced the television lights and tattersall pants of the establishment press in a small coffee house near Central Square yesterday.

Thursday, 600 feet of film, tapes and journals they had collected for a book to be published by Simon and Schuster and left with a Canadian professor were confiscated by U. S. customs when the professor tried to bring them over the border. Brigade members claim they themselves were harassed, and much of their literature and souvenirs confiscated, when they crossed the border from Canada last week at Calais, Maine.

Six hundred more Brigade members left Canada for Cuba last week to help harvest the crop. Their goal, they say, is to help Cuba achieve sugar production of 10 million tons, which will allow the government to purchase harvesting machines and free the people for "more meaningful" work.

They may not have found the work meaningful, but they said in their press release, "Many of us felt we were doing truly purposeful work for the first time in our lives ... Accustomed to finding our jobs alienating and destructive, we grew to understand the dedication to work of a people united for their common good."

Michael Kazin '70 said the Cuban people love their work so much that city people volunteered their free time and weekends to go out into the fields and harvest the crops. Even Fidel Castro, he said, spends four hours each day cutting cane, and "cuts like hell."

"In the American press you read of Cubans working extra hours and they give you the impression they're being forced to do it," Kazin said. "On Sunday in Havana, I saw people joyously laughing and singing and planting coffee trees."

While Brigade members wanted to talk about how impressed they were with the Cuban economic, medical, and educational systems, the newsmen and newswomen were more interested in their views on revolution and similar conduct in the United States.

FIFTY YEARS LATER NOTHING HAS CHANGED JUST ASK SEVENTIES GRAD BERNIE SANDERS

Dorothy Devine said, "I was revolutionary before I went to Cuba, and I'm a revolutionary now." To which Kate Hickler '70 added, "Seeing Cuba gave us all a sense of hope."

"The job I see for myself now is not to pick up a gun," Miss Devine reassured newsmen. "That wouldn't be a revolution but a coup d'etat, if the people didn't understand what we were doing."

Mike Landis said, "I used to shout 'Off the Pig,' but now I realize that it's not the pigs' fault-not the people's fault. I don't even think Rockefeller is an ogre. It's just the system we're under, and a matter of convincing people it's not the best one. I hope we can change things as smoothly as possible."Asked if she wanted to bring freedom to the United States "the same way it was brought to Cuba" (ie. through revolution), Miss Hickler quoted from the Declaration of Independence.

"Yes," said a newsman, "but do you think that sort of thing is realistic in this day and age?"

In 1993, journalist Michael Kinsley was at the height of his powers. After serving as editor of magazines like the "New Republic" and "Harper's", he was host of ...

Michael Kinsley is a Contributing Writer for Vanity Fair, where his column appears monthly. Over a long career in the media, he has been Managing Editor of the ...

Apr 28, 2014 - (Michael J. Fox, since you ask, was only thirty when he got the bad ... The summary of my performance starts out pleasantly: “Mr. Kinsley is a ...

Feb 19, 2017 - Michael Kinsley: 'I would like to give living for ever a try'. Interview by Kate Kellaway. The American journalist on ageing, coming to terms with ...

FIFTY YEARS LATER A LIBERAL IS STILL A LIBERAL

Cuba, Que Linda Es Cuba? Notes on a Revolutionary Sojourn, 1969

From cutting cane with Fidel to dining with Viet Cong soldiers, some memories from a trip to Cuba with the first contingent of the Venceremos (“We Shall Win”) Brigade.Michael Kazin ▪ August 17, 2015

I spent two months in Cuba, from December 1969 to February 1970, not as a student or researcher, and certainly not (consciously, at least) as a tourist. I thought of myself as a revolutionary from the United States—“the belly of the beast”—excited to learn from men and women who had already made a triumphant revolution of their own. With 215 other Americans, I was part of the first contingent of the Venceremos (“We Shall Win”) Brigade, organized mainly by members of Students for a Democratic Society.

With great relish, we were breaking our government’s blockade. A warning stamped prominently on our passports stated they were “not valid for travel” to the “restricted countries and areas of Cuba, Mainland China, North Korea, and North Viet Nam.” But who the hell cared about passports? Richard Nixon and his henchmen were not going to stop us from traveling to the land of Fidel and Che—the citadel of anti-imperialism and socialism in the Americas (if not the world)! We did, however, have to fly into Havana from Mexico City—where what I assumed were FBI agents (but were probably Mexican federal police) snapped our photos before letting us board our plane.

For six weeks, we expressed our solidarity by cutting sugar cane at a camp in rural Havana province. Seventy Cuban Young Communists, most of whom spoke pretty good English, lived and worked with us. That year, most Cubans were mobilized in a economic enterprise one could call Promethean or just plain foolish: to harvest 10 millon metric tons of cane—double the output of any previous year—in order to reimburse big loans from Soviet bloc countries and begin to move their economy toward self-sufficiency. Billboards declaring Los Diez Millones Van! were plastered on buildings and alongside roads all over the island. To that end, the government pulled hundreds of thousands of otherwise productive workers out of their mines, factories, and offices to toil in jobs in the fields.

None of us Yanqui radicals had ever before wielded machetes, let alone to chop down ten-foot-high stalks with sharp leaves without damaging the sugar deposits that lie near the ground. We must have been the least efficient macheteros on the island. But, of course, our real reason for being there was to make a political point, as the almost daily coverage we received in Granma, the Communist Party organ, made clear: the same young Americans who fought for civil rights and protested against the Vietnam war were now showing that they were compañeros of the Cuban revolution too.

The practice of solidarity turned out to be a good deal of fun. The Cubans woke us up every morning with a rhythmic tune of their own or a familiar rock song; one morning, we were surprised to hear the Beatles’ “Back in the USSR” blasting from the loudspeakers. Cane-cutting was splendid exercise, and our hosts treated us to a regimen far more luxurious than that endured by native macheteros. They broke up the workday by bringing us jars of frozen Bulgarian fruit yogurt at mid-morning and then served us a three-course meal at lunch.

In the evenings, after an excellent dinner (and all the cigars we could smoke), we listened to speakers and an occasional Afro-Cuban band. One day, El Lider Maximo himself cut cane with us and then gave an hour-long speech, without notes. All I remember from Castro’s talk was his profound doubt that Lee Oswald was a good enough marksman to have assassinated John F. Kennedy in a limousine moving swiftly away from the Texas Book Depository in Dallas.

One evening, our guests were uniformed soldiers from the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam—better known stateside as the Viet Cong. Through a French interpreter, I had a halting, although pleasant conversation, with one of them—a young man about my age. But the conversation ended shortly after I asked him what the large tricolor medal on his chest signified. The soldier beamed and then responded, in English: “Twenty Yankees killed!” Solidarity, I realized, had its emotional limits.

During our last two weeks in Cuba, we were taken, by bus, on a tour around the island. I filled notebook after notebook with details about health clinics, pineapple plantations, secondary schools, the Moncada barracks in Santiago (where Castro and his men staged an unsuccessful attack in 1953 that became the symbolic beginning of their rebellion), and the Isle of Youth, where the Batista regime had kept its political prisoners. Everywhere, we were treated as heroes and urged to transform our benighted nation as the Cubans had transformed theirs.

It all made good sense to me, at the time. (See the embarrassing piece I wrote for the Harvard Crimson a month after returning from the trip. Although the article is attributed to Che Guevara, the bearded icon had not, in fact, composed it from an unmarked grave in the Bolivian jungle, where he died in 1967.)

However, as time passed, I became more critical of the revolution. The big harvest yielded only about 7.5 million tons of the sugar, and the severe economic dislocation it caused made the Cubans even more dependent on the USSR and its allies in Eastern Europe than they had been before. I also learned that a government I had deemed a paragon of true democracy routinely locked up its opponents, jailed gays and lesbians (many on the Isle of Youth, until the prison there was closed in 1967) as “deviants,” and had no intention of allowing its people to decide for themselves if they wanted the Communist Party to remain indefinitely in power.

Gradually, I also began to recall things I had seen or heard during my time on the island that contradicted the gushing, unqualified admiration I expressed at the time. Fierce-looking policemen and soldiers were ubiquitous, particularly in the cities and near big fields and sugar mills. Several of the young Communists who worked and traveled with us confessed their doubts about Fidel’s backing for the Warsaw Pact’s crushing, in 1968, of the Czech attempt to create “socialism with a human face.” They also mocked the stilted rhetoric in their party textbooks as “too Soviet.” Clearly, few would have felt lucky at all, as the Beatles put it satirically, to be “back in the U.S.S.R.”

Cuba, que linda es cuba / Quien la defiende la quiere más, goes the refrain of a patriotic song I learned by heart on the island forty-five years ago: “How beautiful Cuba is… Whoever defends it only loves it more.” Cuba was certainly “linda”—or beautiful. But one should not have to show one’s love for it by defending the Castro regime, now going on its fifty-fifth year. Yes, Cuba has a fine public health care system and the third-highest life expectancy in Latin America, as well as one of the highest literacy rates in the world—higher than that of the United States and most European countries. But there is little else to celebrate after all these years. Soon, I hope the United States will lift its ridiculous embargo and help give ordinary Cubans the opportunity to build a society entirely worthy of being defended.

Michael Kazin is co-editor of Dissent.

FIFTY YEARS AGO

A LIBERAL IS STILL A LIBERAL

This 'Cuba Solidarity' Group Has Sent Americans To The Island For 50 Years To Protest U.S. Policies

WLRN 91.3 FM | By Aaron Sánchez-Guerra

Published August 5, 2019

For 60 years, the U.S. government has sought to punish Cuba's communist regime through a commercial, economic, and financial embargo – known on the island as the bloqueo. But in that same time, a group of U.S. citizens has also traveled every year with aspirations to work alongside Cubans in sugar cane fields and praise their communist institutions. The Venceremos Brigade, which translates as the “We Will Triumph Brigade," is based in New York and identifies itself as a “Cuba solidarity organization." Members of the group are currently on the island celebrating 50 years of sending willing Americans to the Caribbean country.

Heidi María López, 36, of the Bronx, NY, who is of Dominican descent and has visited Cuba with the group for nine years, said "solidarity" is one of the group's main goals. “And also ... political education to raise the consciousness of U.S. citizens of what is happening here,” she told WLRN from Cuba.

The group sent it first delegation of 216 American students in December of 1969 and their trips have been well documented in academia (and also monitored by the FBI). The Brigade denounces American policy towards Cuba as “imperialist” and says it rejects what it qualifies as anti-democratic attacks on the country’s sovereignty and freedom.

As a protest against Washington's policies in place since 1959, it has sent thousands of willing Americans to engage in a range of volunteer work – like assisting workers in local agriculture and infrastructure projects. The Venceremos Brigade says that encourages exchanges between American socialists and their Cuban counterparts, upholds cultural and educational exchange, and broadly supports the Cuban government.

Brigade members arriving in Havana Harbor, 1970. "Taken the morning we reached Havana Harbor. A small launch filled with Cuban Venceremos Brigade staff motored out to greet us and accompany us to the pier. It was the first time we saw the orange shirts of the Venceremos Brigade."

This year, the Brigade sent its largest group in recent years – over 150 people – on separate trips starting July 23 to commemorate their radical expeditions, now even bolder given President Donald Trump’s policies.

“What is unique about this trip is the context,” María López said. “We are revving up our efforts for people to really understand the policies that are in place and currently being reactivated by this administration."

López said the Trump administration’s new travel restriction policies imposed this year have helped to “undermine the Cuban Revolution” and fueled the original problem that the Venceremos Brigade claims to battle against.

Similar to many leftist organizations, the Venceremos Brigade believes that the economic problems in Cuba are wholly due to decades of the economic blockade and tightening sanctions from the U.S.

Brigade members working in a sugar cane field in Aguacate, Cuba, 1970.

Harvard’s newspaper wrote about the Brigade in 1970, describing it as seeing “the joy in Cuba.” Some of the Brigade's rhetoric hasn't changed.

“We need to end the blockade so that Cuba can choose to be fully participatory in the world economy,” López said. “And for people to be free to come here and see with their own eyes what models for humanity Cuba is offering us. Not because they are perfect, not because they have found the only way, but because we all deserve to live in our full humanity and that includes Cuba.”

The Venceremos Brigade stands for LGBTQ rights, which is in conflict with the Cuban government’s refusal to approve gay marriage, as well as the violent repression of an LGTBQ march there in May.

López said the Brigade acknowledges that Cuba is imperfect in its treatment of the LGTBQ community and that there is always “more progress to be made.”

Ana Rosario, 34, also a Dominican member of the Brigade from The Bronx, has helped Cuban agricultural workers by picking mangoes and guavas on her trip. She brought along her father Victoriano, who is 68.

“I feel like my faith in humanity is restored when I come here,” Rosario said, describing the reality of Cuba as different than the “propaganda” in the U.S.

“I feel that this work is important but even more now that the U.S. government is being even more hostile than ever against Cuba,” she said.

Victoriano, her father, said he has never been a political activist. “What I have been is a human person and I like when governments do something for humanity and I’ve seen that the [Cuban] government, with the little resources they have because of the embargo, they invest in education and health," he said.

According to Granma, the Cuban government newspaper, the last division of the group will be on the island until August 13, where they will pay tribute to Castro on his 93rd birthday.

Copyright 2020 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.

9(MDAyMTYyMTU5MDEyOTc4NzE4ODNmYWEwYQ004))

Aaron Sánchez-Guerra

Aaron Sánchez-Guerra is a recent graduate of North Carolina State University with a BA in English and is a bilingual journalist with a background in covering news on the vast Latino population in North Carolina. His coverage ranges from Central Americans seeking asylum to migrant farmworkers recovering from Hurricane Florence. Aaron is eager to work in South Florida for its proximity to Latin American migration and fast-paced environment of unique news. He is a native of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas of Mexican origin, a Southern adoptee, a lover of Brazilian culture and Portuguese, an avid Latin dancer, and a creative writer.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67012146/1223806254.jpg.0.jpg)