Struggle between human rights and property rights

by Dr Nazmul Alam | Published:Dec 13,2020

Nurse May Parsons, right, administers the Pfizer/BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine to Margaret Keenan, left, 90, at University Hospital in Coventry, central England, on December 8 making Keenan the first person to receive the vaccine in the country’s biggest ever immunisation programme. — Agence France-Presse/Pool/Jacob King

A UK grandmother, Margaret Keenan, has become part of history by becoming the first person in the world to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as part of a mass vaccination programme. COVID-19 vaccines have been developed at a record speed in less than a year of the pandemic. Of the several hundred candidates who started the race, Pfizer-BioNtech, Oxford-AstraZeneca, Moderna-NIH, and Sputnik V vaccines are among the front-runners. A fundamental challenge now is to make the vaccines available to billions of people. The UN secretary general, António Guterres said, ‘The recent breakthroughs on COVID-19 vaccines offer a ray of hope. But that ray of hope needs to reach everyone.’

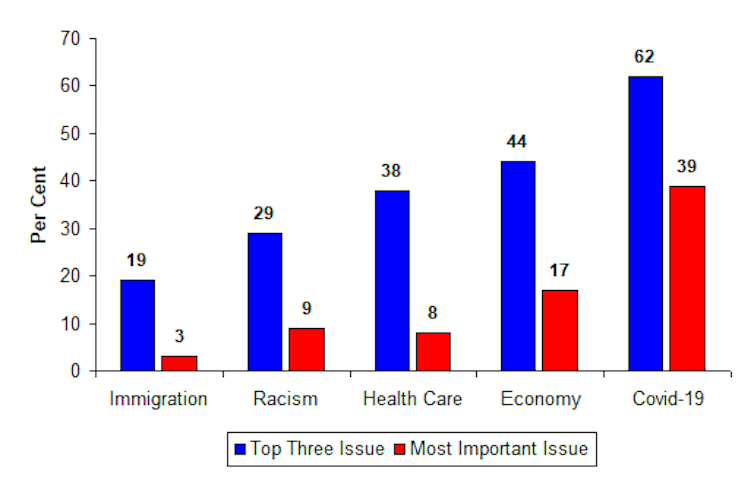

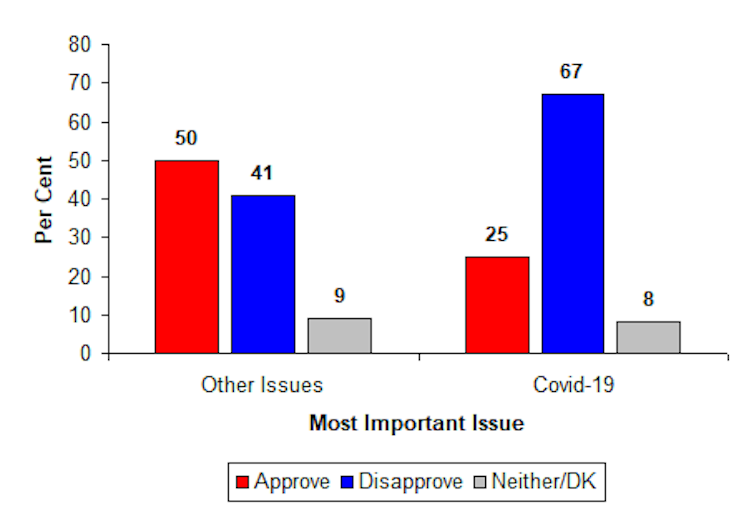

Given the current supply and demand scenario, experts, however, speculated that it could take several years to produce enough vaccines to immunise the global population. Governments are negotiating deals to secure COVID-19 vaccines for their countries. High-income countries are getting more grounds in making deals with major vaccine developers and reserving the lion’s share of the world’s manufacturing capacity. Many of them are contracting for an excess number than they need to vaccinate their entire population before the immunisation even becomes a reality in many low-income countries.

England as the first country that started a mass vaccination programme confirmed its 40 million doses and expects to have 10 million doses by the end of 2020. The United States could begin its mass vaccination within days in December and has already placed an order for 100 million doses for Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine. Canada’s first vaccination could begin by the third week of December on receiving an initial batch of up to 249,000 doses of Pfizer’s vaccine. Canada is, in fact, on top of the global ranking for vaccine contract per capita; it solicited enough doses five times its need. By and large, high-income countries have reserved six billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines through bilateral deals with pharmaceutical companies while low-income countries have not yet signed a single such deal.

To address inequity issues of vaccine availability, the World Health Organisation, Gavi, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations launched a scheme called Covax. It aims to provide lower-income countries with enough doses to cover 20 per cent of their population. So far, Covax has a lifeline which is the only viable way in which citizens in low-income countries to get access to COVID-19 vaccines. However, the Covax initiative faces some serious obstacles of underfunding and non-cooperation of a few big countries such as China and the United States. G-20 leaders in a virtual summit hosted by Saudi Arabia in October 2020 pledged to ensure a fair distribution of the vaccines worldwide but it offered no specific new funding to meet that goal.

South Africa and India have called for the World Trade Organisation to suspend intellectual property rights related to COVID-19 to ensure the availability of vaccines for people in low- and middle-income countries. If accepted, this temporary ban of IP rights would allow local level production of vaccines sooner in large quantities at affordable prices. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical industry and many high-income countries strongly oppose this move. They argued that intellectual property is not a barrier to access and that an equitable access can be achieved through voluntary licensing, technology transfer arrangements and donor-funded approaches. In another argument, they highlighted the agreements that AstraZeneca and Novavax have established with the Serum Institute of India for vaccines. But the counter-argument is that company-led voluntary transfer initiatives have delivered limited results. For example, AstraZeneca’s vaccine manufacturing agreements with Indian and Brazilian companies lack transparency about costs; and Pfizer and BioNTech, whose vaccine candidate has shown promising results, have shown no sign of licensing or technology transfer yet.

Another remarkable campaign signed by world leaders, including Nobel laureates, former heads of state and government, political leaders, artistes, international NGOs and institutions is to declare COVID-19 vaccines a global common good. They urge governments, foundations, charity organizations, philanthropist individuals and social businesses to come forward to produce and distribute the vaccines for all people. Campaigners are pleading for the COVID-19 vaccine formula to be placed in the public domain and made available to any production facility that operates under strict international regulatory supervision. What impact this campaign would make is not clear yet, of course; there are complex underlying causes to untangle the battle of human rights and property rights.

The availability of COVID-19 vaccines is not the only hurdle for the LMICs. There are myriad of systemic challenges that are also part of their ongoing indigenous problems. Insufficient financing, the lack of infrastructure for storage, and the transport and delivery of vaccines are important. COVID-19 vaccines would be expensive for many. Pfizer is charging $19.50 a dose for the first 100 million doses of an order. Moderna plans to charge from $25 a dose. AstraZeneca said that it would sell its vaccine for prices between $3 and $5 a dose. But this no-profit promise could expire before July 2021. Johnson & Johnson also said that it would not profit from the sales of its vaccine to poorer nations and China said that its vaccine would be made a global public good. For countries with huge population, needs to mobilise billions of dollars to procure vaccines for their entire population will further strain their already fragile economy.

Various vaccines demand different storage needs, making it difficult for countries to know how to prepare and whether to invest in cold-chain facilities. Pfizer’s vaccine, for example, has to be transported at -700C requiring deep-freeze airport warehouses and refrigerated vehicles using dry ice. Even when the vaccines arrive in low-income countries, they might lack the transport links and road networks to distribute the doses to all geographic locations. In many low-income countries, only urban areas are well-resourced; health centres in rural areas and informal settlements may not have a working fridge. AstraZeneca’s vaccine can be stored, transported, and handled at normal fridge temperatures of between 20 and 80°C for at least six months. Moderna’s vaccine can also be transported and stored at fridge temperatures, but only for a month.

While childhood vaccinations are a common norm in most low-income income countries, people of all age groups, especially the elderly, will need the COVID-19 vaccine as a priority. This will require the counties to carry out major vaccination education campaigns and logistical support to reach the elderly people. Most vaccines, including Pfizer’s, require two shots. In rural parts of many countries, where people are harder to contact or may live a long way from vaccination centres, some people may not come back for a second shot.

Despite an international agreement to allocate the vaccine equitably around the world, billions of people in poor and middle-income countries might not be immunised with COVID-19 vaccines until 2023 or even 2024. Amnesty International’s adviser Tamaryn Nelson has stressed on agreeing to the intellectual property rights waiver, which is a crucial way to protect the right to health of billions of people no matter where they live. She has also highlighted that we can only put an end to COVID-19 pandemic if we recognise the human rights obligations and ensure that those most in need of life-saving vaccines are not left behind.

Dr Nazmul Alam is an associate professor of public health at Asian University for Women. He also worked as an associate scientist at the ICDDR,B.