By Edmund Berger

Socialism has had a sort of poor track record as of late when it comes to science and technology. From Stalin’s violent repression of Mendelian genetics (and privileging of the pseudo-science of Trofim Lysenko) to the modern contemporary contingencies of anarcho-primitivists, it’s often easy to see what is ostensibly an ideology of advancement oscillating itself between confirmations of the worst despotisms of the dominant, capitalist order, and regressive attitudes towards the raw materials of possible emancipation. The paranoia of computers, simulation, and modelling that blossomed in the 1960s and has persisted until recently recalls, uncomfortably, the anti-scientism of climate change deniers. Where it does embrace technoscience, it adopts them as adjacent to, but not directly bound up within, the emancipatory project. Radical experiments in leftist technoscience, be it Chile’s CyberSyn or the Soviet Union’s own attempts at some form of cybernetic socialism during the Khrushchev years, have fallen by the wayside and are obscured from view. Critical theory continually returns to Situationist discourse, but always seems to focus on those elements that foreshadow insurrectionary anarchism and communization theory. It ignores the constructive side of the ‘construction of situations’ equation – the side on which we can find Constant Niewunhuy’s New Babylon, or Asger Jorn’s celebration of automation.

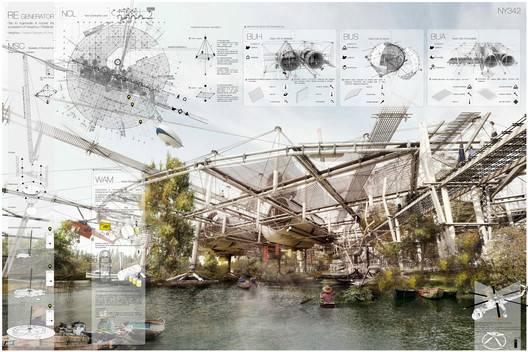

This is what I think is the greatest strength of Nick Srnicek and Alex William’s Inventing the Future – the reinstallation of technoscience as something intrinsic to a radical, left wing program. Automation, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, and the planning of complex economic systems all find their application of the largely imaginal[1] horizon of a post-work world. Far from their inevitable brutal application under capitalist control, they offer a vision of technoscience as emerging from long-term state investment (where it emerges from in our current world, anyways) under the direction of democratic control by the population. Alongside this, breaking beyond capitalism requires the repurposing of existing technologies and infrastructures, to unmoor the class structures and exploitative mechanisms designed within their application. Building on Spinoza, the two suggest that “we know not what a sociotechnical body can do. Who among us fully recognizes what untapped potentials await discovery in the technologies that have already been developed? What sorts of postcapitalist communities could be built upon the material we already have?”[2]

Such a program – of developing new technologies through democratic mechanisms, and the repurposing of existing technologies – implies the generation of a sociotechnical literacy (to borrow a term from Arran James). How can a population be brought up to the level of being able to have substantial input into this sort of dynamic reformation? In a time when anti-scientism has yet to wane, how can the working class – and the surplus populations – learn of complexity, modeling systems, and the way that these technics and techniques exist in reciprocal feedback with the ebbs and flows of the population? True, outlets for learning of these things exists, but they remain shunted off in the university (itself repurposed long ago as training grounds for the petite bourgeoisie) or behind exorbitant paywalls. These privatizations of knowledge and knowledge production find their match in cultural attitudes and mores that tell the working class that these forms of knowledge are irrelevant to their daily situations – unless, of course, there is a perceived threat to their pocketbooks. To build a sociotechnical literacy, essential to a future-oriented hegemonic project, thus requires the building of an educational infrastructure that will help people to navigate the cutting edges of technoscience, while also speaking to them on a cultural level.

Importantly, just such a thing was proposed by socialists long ago, in a tendency that was quickly obscured by the hegemony of Leninism in the Soviet Union, the rise of fascism in Europe, and the American postwar sociotechnical hegemony. I would like to offer a cursory sketch of its history.

From Marx to Mach

How is it that we know the external world, and how do we articulate our knowledge of it in the arrays of paradigms and systems that we bundle under that singular world, “science”? For Kant, knowledge could be determined through synthetic a priori, that is, statements can be known to be true before experience can verify them. This was the trail to transcendental idealism – what we call “consciousness” is the result of the intermingling of sensory stimulation and actions of the mind. The mind gives form, shape, and structure to “our conscious experience that sensory stimulation does not provide.”[3] The world is out there, but the mind plays a fundamental role in articulating that world in ways that we can comprehend it.

It was Ernst Mach who challenged several of these key assumptions. If the principle of a priori was the mean to make knowledge possible, he asked, how is the a priori itself possible? The answer, Mach reasoned was not to be found inside philosophical contemplation, or in the relations going on within the mind itself. This was the positive task of science, to discern the functioning of the world in a way that a foundation can be built in order to build up future forms of knowledge and knowledge production. That which the a priori was aligned – theory – was unmoored from its ontological foundation, and treated as little more than an instrument through which the functioning of the world could be discerned. What mattered more than theory was the understanding of knowledge, scientific or otherwise, as sensation itself. Experience of sensation provides the “pure data” through which we can know. As such, the task of the scientist was to provide “economical description(s) of observable phenomena”; in a challenge to Kantian philosophy, knowledge pivoted on the “adapting [of] thoughts to facts and to each other.”[4]

In order for such a task to be carried out, scientific knowledge could no longer be isolated away from one another in differing fields. “It is the object of science to replace, or save experiences, by the reproduction and anticipation of facts in thought. Memory is handier than experience, and often answers the same purpose,” Mach wrote in Memory and Science.[5] In order to provide an ‘economical’ platform for knowledge, a memory system had to be crafted that brought together disparate fields. In other words, a unification of science had to be fostered. This would become the overriding intention of the Vienna Circle that flourished in Austria in various forms from the early 1900s to the 1930s, bringing together numerous and notable natural scientists, mathematicians and philosophers. Vienna, however, was not the only place that Mach’s influence would reverberate.

Between 1904 and 1906, Alexander Bogdanov published a three-volume work bearing the title of Emperio-Monism, detailing an attempted synthesis of Marxist theory and Machist philosophy. His first spin on Mach is a reinterpretation of the sensation necessary for the production of knowledge. In a foreshadow of the contemporary field of science and technology studies, Bogdanov understands science as a collective experience, circulating through and transcending the networks of individuals, apparatuses, and social organizations that produce it. This function, in many regards, recalls the now well-known Marxist concept of the “general intellect” found in Grundrisse.[6] Like the general intellect, Bogdanov’s science is a social function; this, in turn, entails a rendering of sensation as a collective, as opposed to an individual, experience. Yet science has no monopoly on knowledge. Bogdanov had a strong interest in folk knowledge, the kind of knowledge produced by the entanglement of labor and nature. This mode of folk knowledge functions very much like what James C. Scott describes as “metis”, a “mode of reasoning most appropriate to complex material and social tasks where the uncertainties are so daunting that we must trust our (experienced) intuition and feel our way.”[7] What is important in this Marxist-Machism is not so much the superiority of folk knowledge or technical knowledge, but the feedback that exists between and the possibilities of new forms arising from a mutual co-production.

Like any good Marxist, Bogdanov is attentive to the ways in which dominant (particularly capitalist) social organizations ‘flavor’ the way in which science and technology develop, find their articulation, and are deployed within the social field. In Marxist theory, the organization of society takes places through the superstructure, the realm of family, religion, philosophy, science, the institutions of civil society, which is contingent on the dynamics of the base, where one is to find the modes, forces, and relations of production and the economic system that emerges from it. Through this interplay, capitalism gains the expansionist ability to reproduce its relations. Bogdanov, however, finds this dynamic a bit too simplistic, and ultimately too deterministic, to account for the complexity of historical development. His alternative charts a non-linear movement through science, culture, production, and the way that the labor driving this production is organized. To quote Arran Gare, “For Bogdanov economic life is an integral part of social being, and social being is identical to social consciousness; therefore it is knowledge which is the moving force of history and the main line of social progress.”[8]

Reformulating Marx, he argued that social being has two levels, the technical and the organizational. The organization of activity at the technical level generates technical knowledge or technology… As the technical level became more complex, humans came to need organizational forms. This is the realm of ideology, or what has been called in idealist philosophy, the realm of the spirit – concepts, thoughts, norms, all of those things that would be called ideas in the broadest sense of the word. Bogdanov saw no difference between technical and ideological labor… Techniques are the very essence of human social existence and the primary matrix of social relations, but ideology, the entire sphere of social life outside of the technical process, is also a vital force.[9]

As McKenzie Wark writes, Bogdanov’s perspective is a “labor point of view”, perhaps even more so than Marx’s own, in that while he situates the sensation of experience as the baseline for the production of knowledge, which in turn feeds into the organization of society, as a laboring act committed not by the individual, but by the collective of laborers. “…scientists, artists, and philosophers,” like Mach would argue, “are ‘organizers of experience’”,[10] and communicate this experience through the structures of culture. Culture, then, is intricately bound to the ways in which knowledge is produced and articulated, and thus it is through this complex interplay that culture predicates the organization of production – a starkly different portrait than the predication of culture on the organization of production, as the Marxist base-superstructure dynamic would have it. As long as bourgeois culture persisted, experience would be organized in a way that perpetuated capitalist domination. An attempt to strike out against capitalism without first paying heed to the fostering a new culture that would replace that of the bourgeoisie would ultimately be doomed to fail.

Bogdanov would become one of the Lenin’s major rivals in the early days of the Soviet Union, and his reformulation of Marx clearly challenged many of the essential assumptions of the vanguard party, which carried out its actions on the notion that simply reorganizing the superstructure would fundamentally transform the base. It is for this reason that Bogdanov remains relatively unknown, even on the left, having been quite literally written out of history by Lenin. There is no need to recount the rivalry between Bogdanov and Lenin here, and its relation to wider power struggles in the fledgling socialist republic (though I cover some of it in my earlier essay All That is Solid Melts). What is important here are Bogdanov’s two attempts to build platforms for a revolution in organization, through which a new world can be glimpsed through productive education. The first of these is Proletkult, which attempted to provide the workers with the means in which to create their own culture, and the second is tektology, a sort of ‘science of sciences’ (not dissimilar to the Machist gambit of unifying science) that would allow workers to transcend their status as cogs in the capitalist machine and become worker-engineers, and ultimately worker-scientists.

Srnicek and Williams argue that the left must construct a “counter-hegemonic project” capable of contesting neoliberalism, one that “enables marginal and oppressed groups to transform the balance of power in a society and bring about a new common sense.”[11] This was precisely the program that Bogdanov conceived of with Prolekult; in his own words, “the inherent condition of Bolshevism was to ‘create as from now on in the midst of existing society the great proletarian culture, stronger and more structured than the culture of the bourgeois classes in decline and more immeasurably freer and more creative.”[12] Socialism was not some far-off goal to be attained in the future, following the heroic negation of the bourgeoisie’s power over the proletariat. It was emergent, right in the social fields of capitalism itself, and simply needed the ability to extend this emergence into the world. Funded by the People’s Commissariat for Education (led by a key Bogdanov ally, Anatoly Lunacharsky), Proletkult flourished in a network of individuals and institutions across multiple cities, often aligned directly with the leading trade unions. Arts and crafts studios, painting and cinema workshops, theater and cinematography courses sprung up, located primarily in direct proximity to factory shop-floors. The influence of the most cutting-edge and technologically-oriented of the modernist avant-gardes flowed through these hotbeds of “proletarian art”, including futurism and constructivism. Writes McKenzie Wark:

Proletkult was a movement with a mission: to change labor, by merging art and work; to change everyday life, by developing the collaborative life within the city and changing gender roles and norms; and to change affect, to create new structures of feeling, to overcome the emotional friction of organizing the labor that in turn organizes nature around its appetites.[13]

Importantly, Proletkult was to break with the student-teacher dynamic that characterizes the majority of education, cultural or otherwise. Just as James Scott defined metis as a sort of labor-knowledge that developed through cooperation within and against nature, the proletarian culture was to be self-generating from the self-organization of the workers themselves. Platon Kerzhentsev, a Bolshevik party official and Proletkult leader, wrote that the network’s studio systems “break with the principle of authoritarianism and are built on the comradely basis of equality and collective creativity.”[14] Self-organization, the Proletkultists recognized, was contingent on the fostering of physical and mental infrastructures, and the subsequent politics of organizing the environment. A leftist, proletarian hegemony had to be built towards, and was never a given against either the bourgeois hegemony or even that of the Marxist-Leninist party – as the subsequent dismantling of Proletkult, and the later dismantling of the Soviet Union, would show.

If the proletariat was to become the ‘organizers of experience’, this ambition could not be limited to the production of culture alone. A proletarian culture necessarily entailed a proletarian science, one that like Proletkult could be self-organizing and capable of superseding the scientific knowledge/folk knowledge divide. Such was the goal of tektology, defined by Bogdanov as “a general study of the forms and laws of organization of all elements of nature, of ourselves, practice, and thought.”[15] The debt to Mach is clear: tektology would provide an ‘economical description’ of experience, while also moving towards a unity of science that allowed the translation of insights and practices from one field to the next. As an educational platform, it would ostensibly also serve as the platform for future forms of scientific thought, theory, and practice. It is interesting to note that Bogdanov borrowed the term “tektology” not from the Machist continuum, but from Ernest Haeckel; Haeckel, also one of the leading proponents of Darwinian theories of evolution, had been a major proponent of German Naturphilosophie – the school of thought generally associated with Fichte and Schelling that sought to establish the foundation for the natural sciences through the elucidation of general rules and forms of organization governing nature in its totality. A Machist-Marxist tektology would seek to no longer maintain this effort in the hallowed halls of philosophy, but to instead inscribe in the practice of labor.

“The methods of all sciences are for tektology only modes of organization supplied by experience,” wrote Bogdanov.[16] The organization established by natural processes proceeds all other forms of organization, which form themselves within and against nature itself. Thus, all questions tend towards the question of organization. The concept of the dialectical synthesis has no bearing here; organization was never in the primordial past some harmonious totality, nor will it be in the future – communist or otherwise. Nature naturally disrupts all bids for utopia. If one can experience nature, and thus know it, make it into science, this experience is based on pre-existing organizational platforms (such as the self-organizing proletarian culture emerging from the Proletkult infrastructure). Tektology, therefore, “was meant to be a design practice for organizing organization, conceived under very real conditions of scarcity and disorganization, but under no illusions that a rosy and harmonious future lay ahead.”[17] If proletarian science was to take root, it needed an infrastructure that allowed the navigation of this tumultuous hyperchaos. Bogdanov lays out a variety of key concepts, which for him served as the essential baseline for the general rule sets governing this chaos:[18]

Environment – that which is always there, always there and composed of systems

Conjunction – the coming-together and overlapping of two systems embedded in this wider nature

Boundary – the insulation for a given system that must be “breached” in order for conjunction to take place

Linkage – the intermingling and interconnection of elements from different system, taking place in the conjunction’s overlapping zone

Ingression – the emergence of a new system or systems from the linkage

Disingression – the mutual breakdown of systems in conjunction

Equilibrium – the act of boundary stabilization in the event of disingression

Crisis – the movement of systems towards a point of disequilibrium

Conservative selection – the preservation or destruction of an organizational system in an unchanging environment

Progressive selection – “a change in the number of elements in a system that maintains a dynamic equilibrium with a changing environment.”

Egression – a system composed of multiple subsystems, usually bound up together under the direction of a primary system

Degression – the remnants or leftovers of a system’s actions

As this handful of concepts and brief, truncated definitions, the swerving of systems from stability to instability and back again is central to Bogdanov’s tektology. As a science of systems, the concern of tektology is not only the ability of the workers to higher modes of intellect and organization, but to discern the patterns of self-organization latent in nature at all scales. Even more importantly is the recognition that systems operating on different scales interact with one another, generating new systems or collapsing the old ones in kind. The self-organization of knowledge, labor, and culture, then, is established in the context of a wider swath of self-organizing systems, and remains perpetually embedded within them. Bogdanov’s tektology, in other words, anticipates the whole of second-order cybernetics, systems theory, and complexity theory, albeit in a rather reduced and premature way. The reductionist nature of his approach, however, cannot be dismissed outright, for his is simply an attempt to present what Mach had suggested: the collecting and arrangement of generalized experiences, through which the ability to know can flourish.

Indeed, many have suggested that German translations of Bogdanov’s tektological reflections influenced both Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the father of general of general systems theory, and Norbert Wiener, the leading theorist and proponent of cybernetics in the years following World War 2. While this remains the subject of debate, there are remarkable congruencies between his work and those of these later thinkers. To quote Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi,

Like Bertalanffy, Bogdanov recognized that living systems are open systems that operate far from equilibrium, and he carefully studied their regulation and self-regulation processes. A system for which there is no need of external regulation, because the system regulates itself, is called a “biregulator” in Bogdanov’s language. Using the example of the centrifugal governor of a steam engine to illustrate self-regulation, as the cyberneticists would do several decades later, Bogdanov essentially described the mechanism defined as feedback by Norbert Wiener, which became a central concept of cybernetics.[19]

For the descendants of Bertalanffy and Wiener, such as the complexity theorists working at the Santa Fe Institute, these complex systems become tinged with the attributes of the neoliberal ideology. The ability of systems to self-organize becomes the self-organization of free agents moving and exchanging in the marketplace, swirling about and coalescing into the beautiful swarm of commerce. Tektology stakes itself out against these interpretations far in advance, with Bogdanov having attacked the atomistic worldview as the basis for capitalism’s projection of hyper-individualism radiated from the belief in the self’s absolute agency. While indebted to Mach’s own critique of atomism, tektology, like Proletkult, always maintained itself in the context of collectivity, of generalized experience and intellect encompassing multiple bodies encountering nature together. Everything unfolds under the socialist horizon.