Creating a New Architecture of Justice and Healing

By NICOLE CAPOZZIELLO |

The Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola holds more than 6,000 men, three-quarters of whom are Black, in an area larger than Manhattan. Angola, which takes its name from the slave plantation that once occupied the site, is a place synonymous with draconian sentences and nightmarish conditions. But even here, a special level of dread has been reserved for a nondescript cement complex called Camp J. From its opening in 1976 until its closure in 2017, Camp J housed thousands of people in solitary confinement, mostly as punishment for breaking prison rules. At any given time, up to 400 men were held there in intense isolation known as extended lockdown.

Men in Camp J lived in four cell blocks, in cells measuring 6×9 feet with no windows and no direct access to natural light or ventilation. A long, dark corridor ran along each block, with louvered windows that let in only a modicum of light and air, and a few industrial fans as the only relief from the Louisiana heat. Self-harm was commonplace, and suicides were far from rare. More than once, corrections officers assigned to the unit walked off the job. The cells were compared to dungeons, by people imprisoned there and outsiders alike.

Solitary confinement cells like the ones in Camp J don’t materialize out of nowhere. Long before they are erected, before they bear witness to countless hours of human misery, these cells exist as mere lines on a blueprint, the result of an architect’s pen put to paper.

Architects invested in human rights have long been concerned with the ethos and effects of the American criminal justice system—and with their profession’s role in designing torture sites. In 2013, Raphael Sperry, an architect and the president of the nonprofit Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), began a campaign to pressure the American Institute of Architects (AIA) to alter its Code of Ethics. His goal was to bar AIA members from designing execution chambers and solitary confinement cells. Last December, the campaign finally succeeded, placing one more roadblock in the way of jurisdictions intent on locking people up in conditions that amount to torture.

“When I talk to people about the practice of solitary confinement, the most common question I get is ‘but what are you going to do about the worst of the worst people?’” Sperry said in an interview. “And I say, ‘if you want to talk about the worst of the worst, let’s talk about the worst of the worst buildings.’”

Designing Torture

The U.S. criminal justice system’s values of punishment and retribution are never more apparent in the built environment than in solitary confinement cells, where they are cast in reinforced concrete and steel.

Long-term solitary confinement in the United States took root in 1829, as an experiment at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, which was designed and built to enable its residents to be held in total isolation. Intended to encourage self-reflection and remorse, the isolation was instead profoundly harmful, and by the early twentieth century, the practice had been largely abandoned. Today, the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site serves as a monument to the failure of solitary confinement.

But the use of solitary did not remain in the past. It resurfaced in the 1980s, as the U.S. prison population exploded and policymakers turned away from any notion of prisons as places of rehabilitation. Since then, units and entire institutions created to achieve “total control” have proliferated: California opened Pelican Bay State Prison in 1989, and ADX Florence in Colorado, the first federal supermax, followed in 1994. Today, more than 40 states have supermax prisons built for extreme isolation, and a variety of solitary confinement units can be found in correctional institutions across the country.

“I’ve been in prisons and jails all over the country, New Mexico, Nebraska, Oregon, North Dakota, Georgia, Louisiana, among others, and their solitary units all look rather different. There are some architectural commonalities, but the level of noise, how deep it is in the prison, the temperature, the cleanliness, the technology, all greatly varies,” said David Cloud. He is research director at Amend, an organization based out of the University of California San Francisco that works to abolish systems designed to inflict harm as well as to immediately reduce the harm caused by these systems. “But the thing they share, whether it’s a newer supermax or a more cheaply built solitary unit, is that it’s a place that’s meant to isolate, deprive, and dehumanize people.”

These places have done so successfully and with great consequence; about 5 percent of all incarcerated people in the U.S. are held in solitary, but as many as half of prison suicides occur there. Most of those who survive their time in solitary experience permanent damage to their psychological and physical health.

“In society… they have learned that animals being in a closed area is inhumane. But they treat human beings here in a worse way,” wrote Herman Wallace, a member of the “Angola 3” who endured 41 years in solitary. “They put people here in a six by nine cell; they are not going to put animals in a cage like that unless they are doing some experiment with the animals and trying to kill them. That is what they are doing to these men; they are killing them slowly and surely.”

Public debates about solitary confinement often look at how this practice of torture metastasized within the now decades-long failed experiment of mass incarceration. People consider the values that underpinned it, the policies that calcified it, the harms to and unmet needs of those subjected to it. While the onus has been rightfully placed on the enormous machine of corrections, it’s easy to forget that other professions and individuals have played an essential role as well.

Prison design is highly specialized and often not particularly competitive, due to both the ethical dilemmas it presents and the challenges inherent to working with the client—which may be a local, state, or federal correctional system or a private prison contractor. “Justice architecture” can also be highly profitable; governments are typically willing to write a blank check for the promise of public safety, making construction budgets, like the budgets of departments of corrections themselves, huge. But these funds are used to build out the security and technology of a space, not to improve the lives and opportunities of those living and working inside of it.

“Public safety is not achieved by bars and barbed wire and pepper spray—it just bottles up the problems you’re hoping and claiming to address,” said Cloud.

Evolving Standards

When Sperry and ADPSR began their campaign in 2013, the AIA resisted taking a stance on capital punishment and solitary confinement, citing the legality of both in the United States. Sperry countered with the argument that solitary confinement in excess of 15 days has been deemed torture by the United Nations. Therefore, he argued, complicity in the practice is in violation of the AIA’s own Code of Ethics, which instructs members to “uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors.”

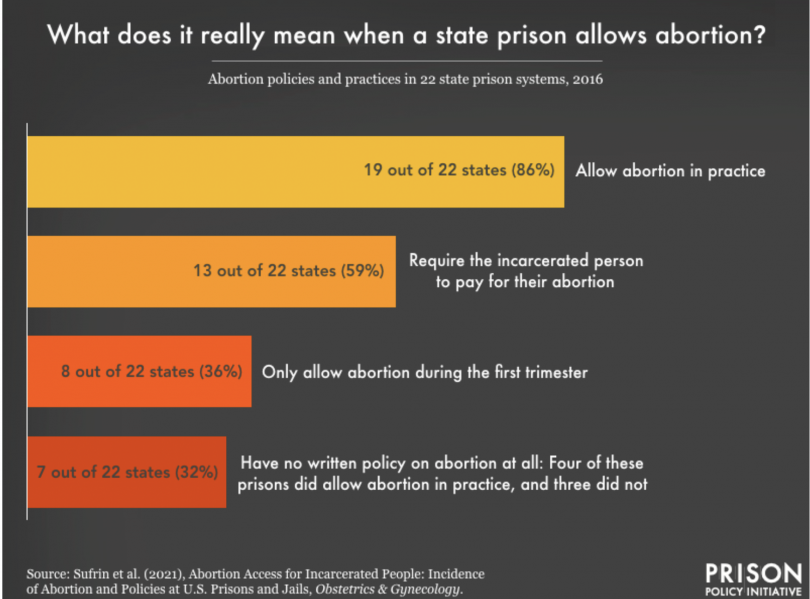

After years of education and advocacy, the AIA finally agreed. In December 2020, the organization changed its ethics rules to prohibit its 95,000 members from designing spaces intended for execution or torture, including solitary confinement. “With the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, there was a need for white institutions, including architecture, to figure out what they could do for people of color,” said Sperry, who credits the adoption to a confluence of receptive leadership at the AIA and this political energy. (While racial and gender diversity in the profession has been growing, only 2.5 percent of architects are Black and 11 percent are Hispanic or Latino. Over 70 percent of American architects are men;).

Sperry is hopeful that the change will have concrete impacts. Under the new ethics rules, AIA members working on prison-building contracts will be unable to design a solitary wing or building. While the construction of new prisons is less commonplace today than during the prison boom of the 1990s, solitary confinement units remain a standard feature.

“If you think that your client is intending to keep people in these spaces for more than 15 days, you, as an AIA member, wouldn’t be able to design that,” said Sperry. who believes that at minimum this creates an obstacle for the client. Rules of Conduct are mandatory, and according to the Code of Ethics, violation by a member architect “is grounds for disciplinary action by the Institute.”

“Members will have to talk to their clients about protecting individuals’ human rights,” he said. “And I hope that the bigger outcome will be in just reconsidering jail projects entirely.”

The ethics code change may also help by giving advocates and lawyers ammunition when bringing forth court cases on solitary confinement. “When you try to bring a case that solitary confinement is cruel and unusual, you have to show ‘an evolving standard of decency,’ and I sure think this is one,” said Sperry. “Architects used to design solitary confinement cells and now they won’t? That’s a great case, and I’m hoping lawyers will make use of this.” The idea of meeting society’s “evolving standards of decency” is one the U.S. Supreme Court first articulated in 1952 as a test of whether the state violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

“We have to start thinking more creatively about solutions to big issues, including the structural problems that drive mass incarceration,” said Cloud. New approaches will only become more needed and unavoidable, as climate change and public health crises—not the least of which has been the COVID19 pandemic—are increasingly felt in our built environment, including prisons.

Transforming and Memorializing Carceral Spaces

For proponents of change both outside and inside the criminal justice system, a big question remains: if we succeed in ending the inhumane practices for which these spaces were built, what do we do with the spaces that already exist? Solving this problem again depends upon the participation of architects and designers.

“One of the biggest challenges of addressing solitary is the physical space,” said Cloud. “You can change the name of the unit, you can let people out of their cells more often, but at the end of the day, it’s still a bleak environment within a system meant to disappear and dehumanize people.” In many cases, no amount of ingenuity or goodwill can transform small, dingy cells, expressly designed to cause harm, into livable units. The only answer is to stop housing people in the units altogether.

Take Angola’s Camp J, which was closed in 2017 due to external pressure from advocates and internal pressure from staff.

From 2017 to 2019, the Vera Institute’s Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative partnered with state corrections departments to look at and address their use of solitary; in Louisiana, this work was led by David Cloud. As a part of their research, Cloud and others, including a team from Boston-based architecture firm MASS Design Group and Loyola University law professor Andrea Armstrong, held a series of focus groups with incarcerated people and staff. In this participatory research, they asked people who had endured solitary confinement at Camp J: Could a dilapidated and deserted space, associated with trauma and agony, be reconfigured to help improve the lives of incarcerated people?

The first proposal was to house a residential, multi-generational living and mentoring program, grounded in tenets of racial and restorative justice, a model that Vera had pioneered elsewhere with its Restoring Promise initiative. The second idea was to repurpose the building as an Educational Center focused on reentry, in response to residents’ and staff’s desire for more opportunities for vocational skills and education.

However, others thought that Camp J was simply irredeemable. Cloud recalled, “Some people said, ‘That place has so much baggage, so much trauma. It’s haunted.’” This led to a final suggestion: to ceremoniously raze the building and replace it with a space of remembrance, moral reckoning, reflection, and healing, which the proposal called an “Interpretive Ruin.”

As of yet, none of these ideas has been realized. According to Cloud, while there was support from Louisiana State Department of Public Safety and Corrections leadership to pursue these ideas, resources and local politics seemed to stand in the way. Then, in March of 2020, Camp J was reopened as a quarantine facility to house incarcerated people who tested positive for COVID19. When cases fell, it was closed, but as they have risen within state prisons it was reopened once again.

Though still unfinished, this initiative fits into a broader movement to create spaces that memorialize people’s lived experiences, facilitate healing, and embody a different vision of justice.

Two nonprofit architecture firms, Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS) and MASS Design Group, are at the forefront of this work. MASS’s creations have included the Soil Collection for the Memorial to Peace and Justice, a collaboration with the Equal Justice Initiative featuring soil from lynching sites throughout the south, and the Writing on the Wall, a traveling exhibition and installation composed of over 2,500 essays, poems, letters, stories, drawings and notes written by people in prison around the world.

DJDS’s projects have also included ongoing work to transform the Atlanta City Detention Center into a Center for Equity; peacemaking centers; and resource hubs like Restore Oakland, a “center for restorative justice and restorative economics.”

“In order to heal, you need to be connected, and shown support, shown love, shown that people believe in you. And that’s the opposite of solitary confinement, and prison in general,” said Garrett Jacobs, DJDS’s Director of Advocacy and Strategic Partnerships. “We’re about building up what prison has often broken down. We believe in abundance—there is enough love, there are enough resources, there is enough space for people. And with this, we believe that people can transform.”

DJDS is committed to working with people who have been directly impacted by the criminal justice system, and applying trauma-informed principles throughout the process. Jacobs said it is important to them to adhere to a universal approach to design, one that asks: “How can we design to counteract the worst-case scenario someone may have been exposed to?” Arguably, this scenario is solitary confinement, a setting of torture and deprivation, lacking any pretense of nature, connection, or life.

At design workshops, DJDS asks participants to explore the question of what justice buildings would look like if accountability, healing, and transformation were the goal. “When you go into a creative process with someone who has experienced something as difficult as incarceration, you have to think about the many things that could shape their mindset, so they can unlock all of their gifts,” said Jacobs.

As members of underserved communities and survivors of a total institution such as prison, participants often have had little control of their environment and little reason to hope. A setting in which they are treated with respect and asked to imagine a different reality can be foreign or even stressful. Jacobs said that participants soon warm up, imagining and creating prototypes using prison-approved materials like construction paper, glue sticks, and acrylic paint. And while each design looks different, there are elements that they strikingly share: light, openness, the color green.

“But visualizing these spaces is not enough,” DJDS Founder and Executive Director Deanna Van Buren put forward in a TED Talk. “We have to build them.” And that is what some architects are doing. While they recognize that many of these undertakings are immense, so are the possibilities. In their work, informed by the experiences of impacted communities, they are inventing and propagating new types of buildings, centering on restorative justice and offering alternatives to the courthouses, holding centers, and prisons of our current punitive system.

One by one, these structures are migrating off of paper, manifesting a new era founded on intentionality rather than complicity. In this future, human beings are no longer warehoused in spaces of poured, reinforced concrete, and justice architecture lives up to ideals beyond retribution, control, and disconnection. It is an era designed for a new experiment: healing.

By EVENTS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS | December 3, 2021

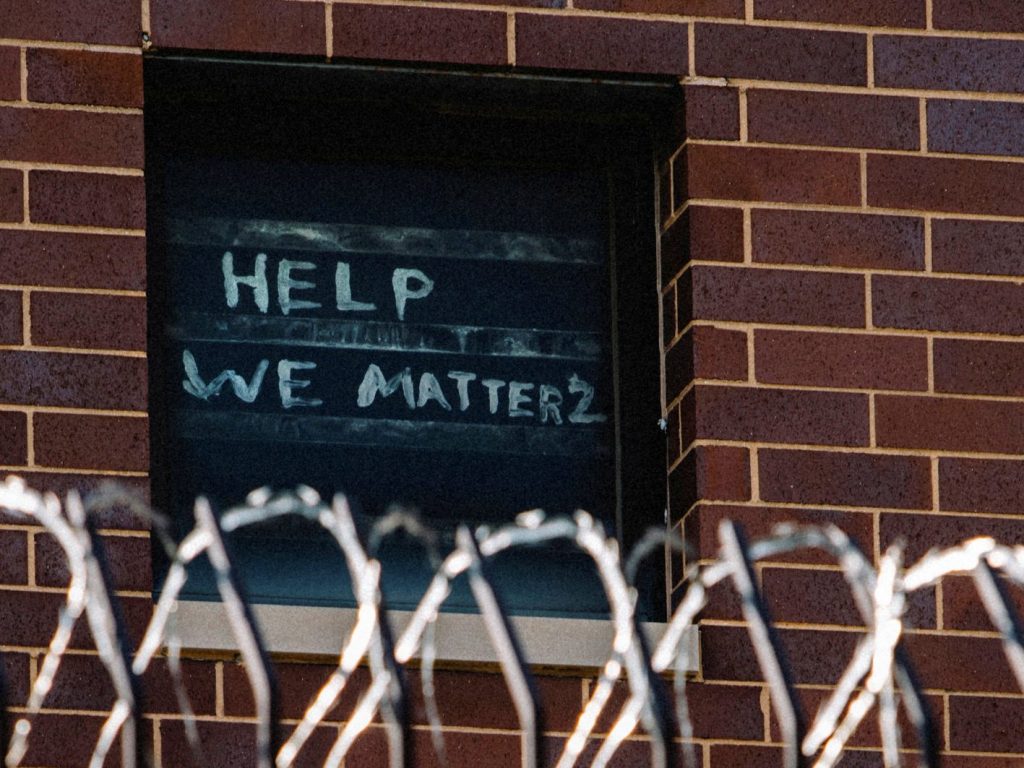

Earlier this week, on #GivingTuesday, we emailed this message to our supporters, asking you to think about the tens of thousands of individuals living in solitary confinement in the United States. These people woke up locked alone in small cells. They ate their meals alone, spent hour after hour entirely alone, and then fell asleep alone. Doubly isolated—first from their families and communities beyond the prison walls, and then from any human contact within them—many will continue to live this way for weeks, months, years, or even decades. Some will not survive; others will never fully recover.

When Solitary Watch began its work in 2009, our slogan was “News from a Nation on Lockdown.” We were a small outfit with a large mission: to make sure the world knew that at least 100,000 people—the majority of them Black and brown, and many with mental illness and other vulnerabilities—were being tortured daily in U.S. prisons and jails. Over the next twelve years, we reported exclusively on the use of solitary confinement across the country and published hundreds of first-hand accounts of life in state-imposed isolation. Our work has been instrumental in exposing the prison within a prison that is solitary and fueling movements nationwide.

SUPPORT OUR CRITICAL WORK TODAY AND YOUR DONATION WILL BE DOUBLED.

Real change on this issue had just begun when the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic made a different version of “lockdowns” part of the world’s collective experience. While people around the world struggled with restrictions and isolation, the trauma of the pandemic was magnified behind bars. Rather than releasing people to save lives, authorities turned to prison lockdowns that lasted months and longer. Inside prisons and jails, the primary response to the pandemic was mass solitary confinement.

Solitary Watch’s research and analysis of this crisis formed the basis of a report that received widespread media attention and changed the terms of debate about Covid in prisons. We found that the use of solitary confinement increased by 500 percent in the early months of the pandemic, when lockdowns placed more than 300,000 people in prolonged isolation, despite far more humane and effective alternatives.

At the same time, we worked closely with incarcerated journalists to publish inside accounts of the contagion’s spread through prisons. Solitary Watch Contributing Writer Juan Moreno Haines wrote of the ineptitude and callousness that characterized the response at California’s San Quentin, where authorities essentially introduced the virus into the prison through transfers, and then when people fell ill, placed them into appalling conditions in solitary confinement units. Juan continued to send dispatches from his isolation cell after he himself contracted the virus.

Solitary Watch also reported on how solitary confinement was used to punish whistleblowers and suppress protests during the pandemic as people behind bars—who in 2020 contracted Covid at a rate as high as five times that of the general public—desperately tried to keep their time in prison from becoming a death sentence. When few were listening, Solitary Watch helped ensure their voices were heard.

As the Covid-19 pandemic lingers on, its lessons are already being lost: Mass incarceration is deadly, and the lives of those inside are too often treated as expendable. And solitary confinement isn’t a public health strategy; it’s torture

These are the truths that we need to carry forward in this critical time. But to do so, we must ask for your support. If you missed making a donation to Solitary Watch on #GivingTuesday, please donate today to help expose the torture and end the silence of solitary confinement.

YOUR GIFT TO SOLITARY WATCH TODAY WILL HAVE TWICE THE IMPACT.

Now is an especially good time to give. If you make a recurring donation today, NewsMatch will match the amount 12 times over. Every one-time donation will also be matched up to $1,000. Please give now so your generosity can be doubled. Every contribution makes a difference.

Thank you.