Simon Druker

Sat, August 26, 2023

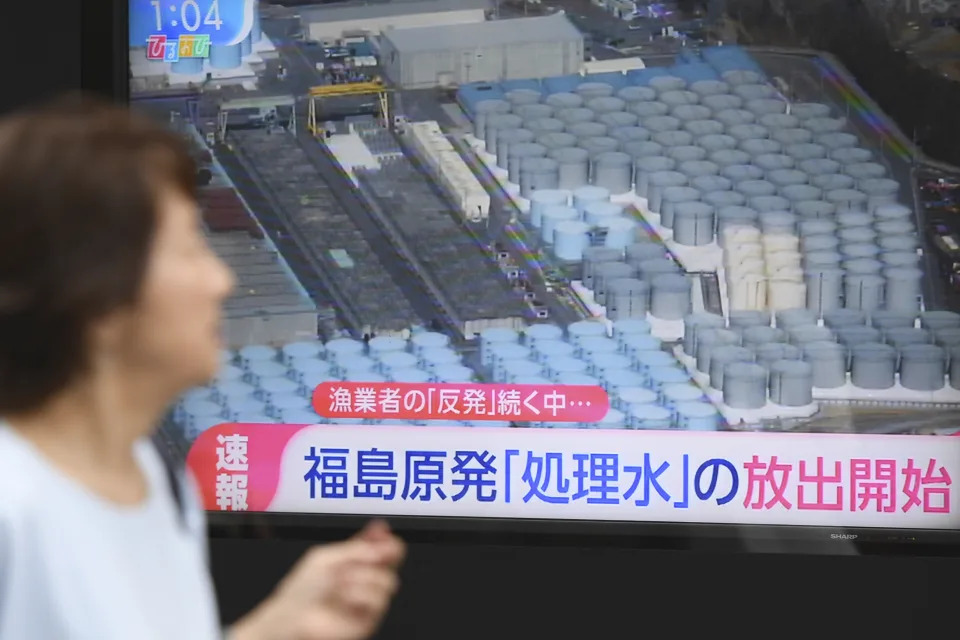

Fish samples from the ocean around Japan’s Fukushima nuclear complex are registering normal and do not contain radioactive contaminants after the discharge of treated wastewater from the plant, officials said Saturday. File Photo by Keizo Mori/UPI

Aug. 26 (UPI) -- Fish samples from the ocean around Japan's Fukushima nuclear complex are registering normal and do not contain radioactive contaminants after the discharge of treated wastewater from the plant, officials said Saturday.

The Japanese government did not detect any amount of tritium in the first fish samples taken in the water around the damaged plant.

Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries tested fish caught within five miles of the discharged water, the Kyodo News Agency reported.

The declaration comes after Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings said Friday none of the radioactive element was detectable in seawater samples.

The company expects to gradually release up to 22 trillion becquerels of tritium per year from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station over the next 20 or 30 years.

An aerial picture of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and its tanks containing radioactive water in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, the day before treated water began being released into the ocean. Photo by JiJi Press/EPA-EFE

Officials on Thursday began releasing treated water from the damaged nuclear plant into the ocean, amid strong environmental pushback from the fishing industry and neighboring countries.

China on Thursday suspended all seafood imports from Japan ahead of the water discharge, citing the possibility of tritium contamination.

The radioactive isotope of hydrogen is considered unstable and radioactive. Tritium occurs naturally but can also be produced as a byproduct of nuclear reactors.

The United Nations nuclear watchdog has said the procedure aligned with global safety standards.

Groundwater around the stricken nuclear facility has been contaminated since a catastrophic explosion crippled the site in March 2011.

Testing is taking place within a 25-mile radius of the water discharge site.

More than 1 million tons of water have already been stored for treatment and eventual discharge.

Last year, Tokyo Electric said it would raise seafood at the Fukushima site in order to dispel rumors about contamination.

Officials will continue measuring tritium levels in both water and fish each time treated wastewater from the Fukushima plant is released into the ocean.

Janis Mackey Frayer and Larissa Gao

Sat, August 26, 2023

IWAKI, Japan — In a laboratory on the third floor of a nondescript building here, a group of volunteers pour water from plastic jerry cans through filters into large round-bottomed vessels. Others chop up dried fish and other foods and put them into small blenders about the size of a coffee bean grinder.

These people aren’t trained scientists. They’re mothers who are worried about the legacy being left for their children after the decision to release treated radioactive water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean.

The gradual discharge of an estimated 1.3 million metric tons of wastewater began Thursday, after repeated assurances from the Japanese government and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog, that it is safe.

But around 40 miles away, in the lab where they test water samples drawn off the shore near the plant, the lab’s manager, Ai Kimura, said she was worried that the discharge might ruin the ecosystem in this area on Japan’s central-eastern coast.

“I worry about the negative legacy, which is the contamination,” Kimura, 44, told NBC News Thursday, adding that it was a “negative legacy to our children.”

Ai Kimura. (Arata Yamamoto / NBC News)

The water being released, enough to fill 500 Olympic-size swimming pools and still building, has been used to cool fuel rods in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant’s reactors since a 9.0-magnitude earthquake and tsunami in 2011 set off a meltdown that spewed radioactive particles into the air in the world’s worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl in 1986, in what was then the Soviet Union.

Though the water is filtered and diluted to remove most radioactive elements, it still contains low levels of tritium, an isotope of hydrogen that is difficult to strip out.

Fukushima shoreline. (Arata Yamamoto / NBC News)

The Japanese government and the plant’s operator, the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (Tepco), have said that the water which they say will be released over the next 30 to 40 years and is being held in hundreds of tanks on land, must be removed to prevent accidental leaks and make room for the plant’s decommissioning, more than a decade after the disaster.

Tepco, which has in the past been accused of a lack of transparency, has vowed to put safety first and stop the discharges if problems arise.

Shortly after the first batch of Fukushima water was discharged on Thursday, the IAEA said that its on-site analysis confirmed that the levels of tritium were “far below” the operational limit.

State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said Friday that the United States was also satisfied with Japan’s “safe, transparent, and science-based process.”

There have nonetheless been loud objections from neighboring countries, including China, where customs authorities announced an immediate ban on all imports of Japanese “aquatic products,” including seafood, to “comprehensively guard against the risk of radioactive contamination to food safety caused by nuclear-contaminated water discharges.”

Although the South Korean government reiterated this week that it sees no scientific or technical issue with the water’s release, police in the country on Thursday arrested 16 protesters accused of trying to break into the Japanese Embassy in the capital, Seoul.

Dolly Peng, 23, looks at sushi in a Hong Kong store that has a sign saying it is from Norway, Argentina and Canada. (Cheng Cheng / NBC News )

But according to data posted online by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, water with much higher levels of tritium has been discharged by nuclear facilities in countries including China, South Korea, Canada and France in line with local regulations.

In the area around the Fukushima plant the impact of the disaster is eerily clear. Three miles away, in the town of Futaba, many of the abandoned houses look like they haven’t been touched since the day of the earthquake.

Curtains flap through broken windows, pictures and clocks are still on the walls and debris is strewn all over. Cars and bicycles are covered in dust.

Back in the lab, which operates as a nonprofit called Tarachin and funds its state-of-the-art equipment with donations, Kimura said that its testing had confirmed that radiation levels in agricultural products and the ocean in the accident region had been decreasing gradually.

But she said she feared the discharge might ruin the promising future of this area’s ecosystem.

“If the treated water is once again discharged, we believe that the same tragedy from 12 years ago will be repeated,” she said.

Janis Mackey Frayer reported from Fukushima, and Larissa Gao from Hong Kong.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

MARI YAMAGUCHI

Sat, August 26, 2023

This aerial view shows the treated water diluted by seawater flowing into a secondary water then into a connected undersea tunnel for an offshore discharge at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima, northern Japan, Thursday, Aug. 24, 2023. For the wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, managing the ever-growing radioactive water held in more than 1,000 tanks has been a safety risk and a burden since the meltdown in March 2011. The start of treated wastewater release Thursday marked a milestone for the decommissioning, which is expected to take decades.

FUTABA, Japan (AP) — For the wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, managing the ever-growing volume of radioactive wastewater held in more than 1,000 tanks has been a safety risk and a burden since the meltdown in March 2011. Its release marks a milestone for the decommissioning, which is expected to take decades.

But it's just the beginning of the challenges ahead, such as the removal of the fatally radioactive melted fuel debris that remains in the three damaged reactors, a daunting task if ever accomplished.

Here's a look at what's going on with the plant's decommissioning:

WHAT HAPPENED AT FUKUSHIMA DAIICHI?

A magnitude 9.0 quake on March 11, 2011, triggered a massive tsunami that destroyed the plant’s power supply and cooling systems, causing three reactors to melt and spew large amounts of radiation. Highly contaminated cooling water applied to the damaged reactors has leaked continuously into building basements and mixed with groundwater. The water is collected and treated. Then, some is recycled as cooling water for melted fuel, while the rest is held in tanks that cover much of the plant.

WHY RELEASE THE WATER?

Fukushima Daiichi has struggled to handle the contaminated water since the 2011 disaster. The government and the plant operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, say the tanks must be removed to make way for facilities needed to decommission the plant, such as storage space for melted fuel debris and other highly contaminated waste.

WILL THE WASTEWATER RELEASE PUSH DECOMMISSIONING FORWARD?

Not right away, because the water release is slow and the decommissioning is making little progress. TEPCO says it plans to release 31,200 tons of treated water by the end of March 2024, which would empty only 10 tanks out of 1,000 because of the continued production of wastewater at the plant.

The pace will later pick up, and about 1/3 of the tanks will be removed over the next 10 years, freeing up space for the plant's decommissioning, said TEPCO executive Junichi Matsumoto, who is in charge of the treated water release. He says the water would be released gradually over the span of 30 years, but as long as the melted fuel stays in the reactors, it requires cooling water, which creates more wastewater.

Emptied tanks also need to be scrapped for storage. Highly radioactive sludge, a byproduct of filtering at the treatment machine, also is a concern.

WHAT CHALLENGES ARE AHEAD?

About 880 tons of fatally radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside the reactors. Robotic probes have provided some information but the status of the melted debris remains largely unknown.

Earlier this year, a remote-controlled underwater vehicle successfully collected a tiny sample from inside Unit 1’s reactor — only a spoonful of the melted fuel debris in the three reactors. That’s 10 times the amount of damaged fuel removed at the Three Mile Island cleanup following its 1979 partial core melt.

Trial removal of melted debris using a giant remote-controlled robotic arm will begin in Unit 2 later this year after a nearly two-year delay. Spent fuel removal from Unit 1 reactor’s cooling pool is set to start in 2027 after a 10-year delay. Once all the spent fuel is removed, the focus will turn in 2031 to taking melted debris out of the reactors. But debris removal methods for two other reactors have not been decided.

Matsumoto says “technical difficulty involving the decommissioning is much higher” than the water release and involves higher risks of exposures by plant workers to remove spent fuel or melted fuel.

“Measures to reduce radiation exposure risks by plant workers will be increasingly difficult,” Matsumoto said. “Reduction of exposure risks is the basis for achieving both Fukushima's recovery and decommissioning.”

HOW BADLY WERE THE REACTORS DAMAGED?

Inside the worst-hit Unit 1, most of its reactor core melted and fell to the bottom of the primary containment chamber and possibly further into the concrete basement. A robotic probe sent inside the Unit 1 primary containment chamber found that its pedestal — the main supporting structure directly under its core — was extensively damaged.

Most of its thick concrete exterior was missing, exposing the internal steel reinforcement, and the nuclear regulators have requested TEPCO to make risk assessment.

CAN DECOMMISSIONING END BY 2051 AS PLANNED?

The government has stuck to its initial 30-to-40-year target for completing the decommissioning, without defining what that means.

An overly ambitious schedule could result in unnecessary radiation exposures for plant workers and excess environmental damage. Some experts say it would be impossible to remove all the melted fuel debris by 2051 and would take 50-100 years, if achieved at all.