A rare look at the lousy life aboard China's 'Dragon Palace' submarines

A new report offers a rare look at the conditions in China's growing submarine fleet.

It found the crews suffer from excessive noise, poor lighting and bad air quality.

The question is whether these problems undermine the effectiveness of China's subs.

Chinese sailors have an ironic name for duty aboard submarines: "Dragon Palace." But there is nothing fantastic — or even healthy — about the conditions in China's large submarine force, a new report has found.

Chinese "submariners have long jokingly referred to their boats as the 'dragon palace' in reference to the palace of the dragon king at the bottom of the Eastern Sea in Chinese mythology," explained a new report by the US Naval War College's China Maritime Studies Institute.

In Chinese mythology, Ao Guang is the king of all sea dragons, ruling over them from his underwater crystal palace. But life aboard People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarines is far from palatial, the CMSI report found, offering a rare look at submarine life that is obscured by the Chinese military's secrecy and the regime's widespread censorship and intimidation. It found the crews suffer from excessive noise, poor lighting and bad air quality. The canned foods often served are so tasteless some sailors develop eating disorders.

"Work aboard PLAN submarines can cost personnel their health," said the CMSI report. For example, various surveys over the last two decades found numerous maladies, including mouth ulcers and back pain. "In 2018, researchers from several PLAN institutes and hospitals conducting surveys at a submarine base found that submariners as a profession were prone to lower back pain due to restrictive workspaces, long hours in fixed or contorted positions, and the constant vibration to which they are subjected. Results showed a 33.81%occurrence of lower back pain in commissioned officers and enlisted personnel."

Crews suffer psychological effects from the constant noise and low air quality they're subjected to underway. "Crew members working and living in a submarine's poor microclimate are prone to boredom, fatigue, lethargy, and discomfort, which impacts their psychological state, cognitive abilities, and emotional well-being," the report said. "These problems are further exacerbated by harmful gases, magnetic fields, noise, vibrations, and many other barriers to restful sleep and comfort."

Noise levels aboard Chinese have been measured as high as 90 to 130 decibels, which exceeds even the Chinese military's threshold of 85 to 100 decibels. Sub crews have also reported eyesight problems that stem from the poor quality lighting. "Analysis attributed this to poor lighting causing visual strain and close quarters, causing a problem in the ciliary muscles that regulate changes in eye lens curvature," CMSI said. "Crews requested more lighting in compartments and lighting modes that could provide an indication of day or night."

Meanwhile, medical care during long-duration voyages is lacking due to poorly trained caregivers and unkept medical equipment, the report found.

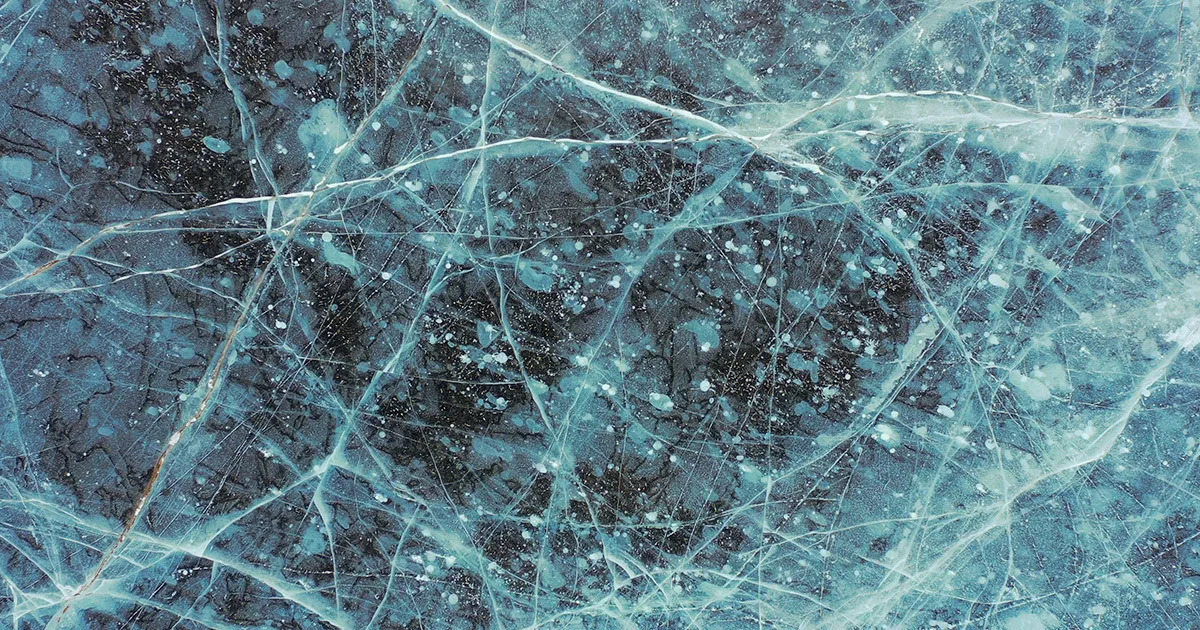

The report found instances that the cuisine on Chinese submarines was so bad it's led to eating disorders.Photo by Artyom Ivanov\TASS via Getty Images

That may be why China's sub force recently turned to traditional Chinese medicine, already used by other branches of the Chinese military. "Until recently, Chinese traditional medicine was not present on board PLAN submarines, since there were no designated positions to administer it," said CMSI.

Sailors in most navies grumble about food. Even US Navy subs, which reputedly have better chow than other ships, have their share of grousing about penal-quality meals. Providing appetizing food for months at a time is a challenge on Chinese subs, whose crews vary from around 60 on a diesel-powered attack boat to around 120 on a ballistic missile submarine.

Though some recent photos suggest an appealing menu, Chinese submarine cuisine still appears to be lacking. "Since submarines prohibit open flame cooking, canned food appears to have been the staple for many years on long-distance deployments," said CMSI. After "the poor taste of canned food eventually drove some sailors to become anorexic," more fresh and frozen food was served. But when "the fresh food runs out or electricity conservation is enacted, submarine crews reportedly begin eating standard field rations, such as the navy's KT-07 nutritional supplement rations. To make up for these conditions, submariners can usually expect a feast to welcome them when returning to shore."

Ultimately, the question is whether these problems undermine the effectiveness of China's 61 submarines. Though most are conventional rather than nuclear-powered, they could be among Beijing's most effective weapons if China were to invade Taiwan.

"Many of the hallmarks of a professional submarine force culture are present aboard PLAN submarines, especially surrounding secrecy, safety, and expertise," CMSI concluded. "Whether it is procedures for equipment maintenance or nuclear reactor safety, the force appears to demonstrate a high level of professionalism and a desire to uphold the highest standards across the fleet."

Chinese submariners have their own "dragon palace culture." This includes activities such as arm wrestling and ping pong contests, as well as other morale-boosters such as shipboard newsletters and poetry readings.

And what submarine force would be complete without its special rituals (that often baffle landlubbers). For example, a ceremony to honor those doing their first long-duration deployments happens when the submarine reaches maximum dive depth, the report said. "Recognized personnel will kiss a buttered hammer and drink seawater drawn from the depths, which is kept within a vial."

Michael Peck is a defense writer whose work has appeared in Forbes, Defense News, Foreign Policy magazine, and other publications. He holds an MA in political science from Rutgers Univ. Follow him on Twitter and LinkedIn.